Constantine IX Monomachos

| Constantine IX Monomachos | |

|---|---|

| Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans | |

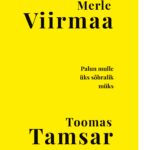

Mosaic of Emperor Constantine IX at the Hagia Sophia.[1] | |

| Byzantine emperor | |

| Reign | 11 June 1042 – 11 January 1055 |

| Coronation | 12 June 1042 |

| Predecessor | Zoe and Theodora |

| Successor | Theodora |

| Co-empress | Theodora (1042–1055)[2] |

| Born | c. 1000/1004 Antioch |

| Died | 11 January 1055 (aged 50–55) Constantinople |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | daughter of Basil Skleros Maria Skleraina Zoe Porphyrogenita |

| Issue | Anastasia[3] |

| Dynasty | Macedonian |

| Father | Theodosios Monomachos |

Constantine IX Monomachos (Greek: Κωνσταντῖνος Μονομάχος, romanized: Kōnstantīnos Monomachos; c. 980[4]/c. 1000[5] – 11 January 1055) reigned as Byzantine emperor from June 1042 to January 1055. A member of the urban aristocracy, Constantine became emperor through marriage to the ruling empress Zoë Porphyrogenita in 1042. The couple shared the throne with Zoë's sister Theodora Porphyrogenita. Constantine's energetic rule was one of the most consequential in the Byzantine Empire's tumultuous 11th century.

Fiscally, Constantine's reign was marked by prodigality, and he depleted the abundant imperial treasury he had inherited from Basil II (r. 976–1025) and his successors. For reasons that remain obscure Constantine debased the gold currency of the empire, the first permanent debasement of the coinage since its introduction by Constantine the Great. In Constantinople Constantine spent lavishly on both personal gifts and religious projects. Presiding over a period of economic expansion, Constantine encumbered the state by his massive expansion of the aristocracy.

In matters of provincial administration, Constantine attempted a series of reforms to varying levels of success. In the power struggle between the urban elite and the Dynatoi which was waged throughout the 11th century, Constantine made overtures towards both. He granted tax exemptions to the Dynatoi through an early form of the pronoia system and freely granted titles, privileges, and gifts of money to the civil elite. In response to the rising importance of civil judges (known as kritai) over theme commanders (strategoi) Constantine created the office of the Epi ton kriseon. Constantine attempted to reform the empire's legal system, centering on the creation of a law school headed by a nomophylax, but had limited success.

Constantine was victorious in two civil wars, foiled several coup attempts and successfully fought off a raid by the Kievan Rus', but was humiliated by the Pechenegs in the West and failed to stop the rising Seljuq Turks in the East. Though the Byzantine Empire largely retained the borders established after the conquests of Basil II — even expanding eastwards through the annexation of the Armenian kingdom of Ani — Constantine is often blamed for the poor state of the army in the years leading up to Manzikert.

In 1054 Constantine oversaw the decisive events of the Great Schism between the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches. His treatment of the papal legates of Leo IX exacerbated tensions between the legates and the patriarch Michael I Cerularius of Constantinople. He died one year later of an infection related to his chronic arthritis.

Traditionally, Constantine Monomachos has been viewed as an incapable, militarily inept emperor and one of the architects of the Byzantine decline of the late 11th and 12th centuries. However, recent scholarship has done much to rehabilitate his reputation as a civil administrator and reformer. He was perhaps the only emperor between Basil II and the Battle of Manzikert to attempt a coherent program of reform, even if this program was flawed and unsuccessfully carried out. Constantine accordingly may be considered the last effective emperor of the Macedonian Renaissance.

Early life

Constantine Monomachos was the son of Theodosios Monomachos, an important bureaucrat under Basil II and Constantine VIII, of the famous and noble Monomachos family.[6] His mother and her name are unknown. Constantine was born around 980[4] or 1000[5] in Antioch. At some point Constantine's father Theodosios had been suspected of conspiracy, and his son's career suffered accordingly.[7] Constantine's position improved after he married his second wife, sometimes called Helena or Pulcheria, a daughter of Basil Skleros,[8] and niece of Emperor Romanos III Argyros.[9] Catching the eye of Empress Zoë Porphyrogenita, he was exiled to Mytilene on the island of Lesbos by her second husband, Emperor Michael IV.[10]

The death of Michael IV and the overthrow of Michael V in 1042 led to Constantine being recalled from his place of exile and appointed as a judge in Greece.[11] However, before he could commence his appointment, Constantine was summoned to Constantinople, where the fragile working relationship between Michael V's successors, Empresses Zoë and Theodora Porphyrogenita, was breaking down. After two months of increasing acrimony between the two, Zoë decided to search for a new husband, thereby hoping to prevent her sister from increasing her popularity and authority.[12]

After her first preference displayed contempt for the empress and her second died under mysterious circumstances,[9] Zoë remembered the handsome and urbane Constantine. The pair were married on 11 June, without the participation of Patriarch Alexius of Constantinople, who refused to officiate over a third marriage (for both spouses). Constantine was crowned on the following day.[13]

Appearance and personality

Constantine was said to rival Achilles and Nireus in terms of beauty.[14] He was described by Michael Psellos as "a marvel of beauty that Nature brought into being in the person of this man, so justly proportioned, so harmoniously fashioned, that there was no one in our time to compare to him".[5] Psellos described "the symmetry of the emperor's body, his perfect analogies, his ruddy hair which shone like rays of sunlight, [and] his white body which appeared like clear and translucent crystal".[14]

His personality has been described as good-natured; he was easily amused and loved to laugh.[5] He charmed practically everyone who knew him, especially Zoë, whom he enthralled immediately.[5] Constantine spent money without restraints and liked to make luxurious gifts to his associates.[5] For example, he gave to the Church many objects of great value, including precious sacred vessels, "that surpassed by far all the others as to dimensions, beauty and price".[15] Constantine also showed clemency and mercy, even in cases of treason.[16] On the other hand, he was described by contemporaries as pleasure-loving, with a temperament unsuitable to his office.[17] He was prone to violent outbursts on suspicion of conspiracy.[18]

Reign

Upon assuming imperial office, Constantine continued the purge instituted by Zoë and Theodora, removing the relatives of Michael V from the court.[19] He opened the treasury to Zoë and Theodora, made large gifts to potential supporters to secure their loyalty, and initiated a round of senatorial promotions.[20] He retained his mistress from his years in exile — a relative of his second wife — named Maria Skleraina. Eventually this arrangement was made official by means of a palace ceremony, and Sklerania was awarded the honorific Sebastē (Augusta).[21]

Early conflicts

By 1040 the situation in Byzantine Italy had become precarious. The permanent settlement of Normans in Southern Italy threatened Byzantine holdings, and a complicated series of diplomatic maneuvers to secure Byzantine control transpired between 1040 and 1042. These centered on Argyros, a prominent Italian from Bari, and culminated in the recall of the Byzantine general George Maniakes from his command in Italy.[22] Fearing enemies at court, Maniakes had himself acclaimed emperor by his troops in September 1042.[23] He transferred his troops into the Balkans and won several battles against imperial armies as he marched towards Constantinople, but in late 1043 he was struck by a projectile and killed in battle.[24]

Immediately after the victory, Constantinople was attacked by a fleet from the Kievan Rus'.[24] There is no direct evidence that the Rus' had colluded with Maniakes,[25][22] but scholarly opinion remains divided. The Rus' raiders were defeated in a naval confrontation in the Bosporus by admiral Basil Theodorokanos by means of Greek fire.[26] As part of the peace negotiations, Constantine married his daughter, Anastasia (by his second wife or Maria Skleraina), to the future Prince Vsevolod I of Kiev, the son of his opponent Yaroslav I the Wise.[27][28] Constantine's family name Monomachos ("one who fights alone") was inherited by Vsevolod and Anastasia's son, Vladimir II Monomakh.[6][29]

Constantine's preferential treatment of Maria Skleraina in the early part of his reign led to rumors that she was planning to murder Zoë and Theodora.[30] This led to a popular uprising by the citizens of Constantinople in 1044, which came dangerously close to harming Constantine as he participated in a religious procession. The mob was only quieted by the appearance at a balcony of Zoë and Theodora, who reassured the people that they were not in any danger of regicide.[31]

In 1045, Constantine annexed the Armenian kingdom of Ani,[32] but this expansion merely removed a key border state between the empire and its enemies. Faced with the challenge of integrating a new people into the Byzantine polity, Constantine chose to persecute the Armenian Church in an attempt to force it into union with the Orthodox Church.[33] In 1046 the Byzantines first came into contact with the Seljuk Turks.[33] They met in battle in Armenia in 1048 and settled a truce the following year.[34] In 1046, Constantine concluded a treaty with the Fatimid Caliph al-Mustansir Billah. The Book of Gifts and Rarities records that on this occasion Constantine gave the caliph a gift of 500,000 gold coins, over two tons of gold.[35][36]

The Pecheneg disaster and civil war

By the time of Constantine's reign the Pecheneg people occupying the Bulgarian steppe had served as a buffer between the Byzantines and the Rus' for decades. In the 1040s however, under external pressure from the Oguz Turks, tens of thousands of Pechenegs migrated South of the Danube. After a period of crisis, raids, and Pecheneg civil war, these Southern Pechenegs were settled by the Byzantine administration in the North Balkans in 1046.[37] This settlement proved controversial with the Macedonians.[38]

That winter, Constantine was faced by the rebellion of his nephew Leo Tornikios, an officer in Adrianople. The reason for his rebellion is uncertain — possibly ultimately a family dispute[39] — but the Macedonian tagmata under his command had become disaffected following their demobilization after the conflict with the Pechenegs,[40] and Tornikos was able to draw in anti-government elements from across the empire. He was proclaimed emperor by the army in the summer of 1047.[41][42] Constantine assembled an army from the jails of Constantinople but this was quickly defeated and Tornikios put the city under siege.[43] Tornikios was on the verge of taking the city but declined to press his advantage and Constantine was able to re-man the walls. Eventually, Tornikios's army was won over by bribes and the rebellion was put down. Tornikios was blinded.[44][45]

The revolt had weakened Byzantine defenses in the Balkans, and in 1048, the area was raided by those Pechenegs still North of the Danube.[46] The same year, Constantine raised a force of 15,000 Pechenegs for his war against the Seljuks in the East, but they mutinied, raided back across the Bosporus, and by 1050 the Northern and Southern Pechenegs had regrouped South of the Danube in open revolt.[47] The Pechenegs plundered the Balkans until 1053, defeating several Byzantine armies.[48] Historian Anthony Kaldellis calls this "the worst string of Roman defeats in more than a century."[49]

Later rule

Constantine's mistress Maria Skleraina died around 1046, and Constantine took a new mistress: an "Alan princess", likely the daughter of a Caucasian lord.[50] Zoë also perished in 1050, and by that point Constantine's health had declined substantially as well: his arthritis was so severe as to render him incapable of walking unassisted.[51]

In 1050 or soon after, Constantine took the extraordinary step of substantially debasing the nomisma, from 24 karats to 18.[52] The reasons for this policy remain obscure; likely it was a way of reducing the pay of inactive theme soldiers while compensating for a large budget deficit.[53] Whatever motivated this action it was received without protest, unlike the much smaller debasement which took place under 100 years before under Nikephoros II Phokas; though much smaller, Nikephoros's currency debasement led to riots and had to be repealed.[54]

It is in this later period of his reign that Constantine is also charged with demobilizing a large portion of the Eastern empire's standing army. Scylitzes, Kekaumenos, and Attaleiates all accuse Constantine of dismantling the Iberian theme, permanently relieving 50,000 standing troops in Armenia of their military duties at exactly the moment the empire had greatest need of them.[53][55] Whether this was a mere fiscalization (i.e. an instance of the conversion of strateia from a military obligation to a tax, an ongoing process in the 11th century) or a genuine disarmament is unclear, as are the motives for this change and its true scope.[56] The contemporary sources are universal in ascribing this decision to Constantine's greed, but this is a historiographic convention applied whenever a new tax is imposed; it is likely the motive was financial.[53] In later years many of Constantine's contemporaries looked back at this moment as the ultimate cause of the disaster at Manzikert.

In 1053, the Normans overcame the Byzantine forces led by Argyrus in Southern Italy before the Byzantines could join with the forces of the Pope.[57] Captured by the Normans, Pope Leo IX sent delegates to Constantinople with intent of allying against the Normans, but instead of normalizing Papal-Byzantine relations, this embassy served to fracture them.

Great Schism

In the year 1054 the tensions between the Patriarch of Constantinople Michael Keroularios and Pope Leo IX reached their boiling point, and personal papal legates of Leo arrived in Constantinople. Constantine warmly received the legates, who before long were openly feuding with Keroularios and the monks of Constantinople. During this feud Leo died, but instead of returning to Rome, they remained in the City with Constantine's encouragement. Constantine urged Keroularios to restore communion between the churches but the patriarch refused.[58] The conflict culminated in the legates issuing an excommunication and placing the bull on the altar of the Hagia Sophia. Keroularios excommunicated the legates.[59] The conflict persisted into late 1054 with more anathematizations following, and ultimately the hopes of Papal-Byzantine alliance in Southern Italy were dashed.[60] Within a few years, the Pope would ally with the Normans instead.

Constantine fell ill in late 1054 and died on 11 January of the following year.[61][62] During his sickness he was persuaded by his councilors, chiefly the logothetes tou dromou John, to ignore the rights of the elderly Theodora, daughter of Constantine VIII, and to pass the throne to the doux of Bulgaria, Nikephoros Proteuon.[63] However, Theodora was recalled from her retirement and named empress.[64]

Administration and legal reform

Inflation of the urban aristocracy

During his reign Constantine substantially expanded the urban aristocracy by his liberal gifts of titles. Indeed, entire new classes of titles and ranks were created whole cloth — thus the previously high-ranking proedros was now outranked by the prōtoproedros ("first among proedroi").[65] In the first place, the sheer number of new elites was unprecedented; so large was their number that the pensions or roga due to these title-holders became an encumbrance on the treasury.[66] In previous centuries these titles functioned as government bonds, bought at a high up-front cost but paying for themselves partly by their pension and partly by their prestige. Constantine disrupted this normal functioning by lowering the price of titles, by giving titles away for free to secure political connections, and by decreasing the relative prestige of titles.[67]

Not only was the volume of new title-holders unprecedented, but so was their composition. Constantine enfranchised the merchant elite of the professional guilds — higher-status professionals such as silk merchants who did not work with their hands. This outraged the old urban aristocracy; Psellos — himself of a merchant elite background — wrote that "The doors of the Senate were thrown open to the rascally vagabonds of the market".[68]

Legal reform

By end of the tenth century, the power of the strategoi over the themes was being rivaled by the parallel civilian administration at whose head sat a judge (krites) or magistrate (praitor). But, unlike the theme commanders, these civilian administrators had no central administrator to whom they reported. To remedy this situation, Constantine created the office of epi ton kriseon, a kind of 'head judge' or 'verdict inspector'.[69]

Parallel to the changes he instituted in administration of justice, Constantine attempted to reform the training of lawyers and judges. By his time the courts had moved far from the Justinianic ideal; even the ninth-century Basilika had fallen out of use. The judges of Constantine's times might consult the newly produced Peira of Eustathios Rhomaios, a compilation of cases from the early 11th century, or simply be expected to learn on the job.[70] Constantine identified the root cause of this perceived deficiency as the lackluster legal education offered by the guild of notaries and sought its remedy in the foundation of a law school: in 1046,[71] he re-founded the University of Constantinople by creating the Departments of Law and Philosophy, giving the direction of the law school to John Xiphilinus under the new title nomophylax.[72] This seemingly commonsense measure drew intense opposition. On the one hand the guild of notaries was slighted, as were the teachers of rhetoric and philosophy who felt Xiphilinus's pupils would be preferred to theirs in the imperial administration. On the other hand, the high court judges of the Hippodrome saw Xiphilinos's teaching as too academic for the needs of the empire. In 1050 Xiphilinus retired to a monastery, and the law school built around him disappears from the historical record.[73]

The school operated in Mangana, at the Eastern tip of Constantinople, which was also the site of a monastery and church founded by the emperor.[74] Constantine patronized the Church and monasteries more broadly, including the Nea Mone of Chios and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. This latter had been substantially destroyed in 1009 by Caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah.[75] Romanos III had secured the right to undertake such a restoration in a treaty with al-Hakim's son al-Zahir, but it was Constantine who finally set the project in motion, funding the reconstruction of the Church and other Christian establishments in the Holy Land.[76] Constantine also provided the funds for the Hagia Sophia to celebrate the liturgy daily, rather than on Saturday and Sunday as had been customary.[77]

Rural administration

Constantine seems to have taken recourse to the pronoia system, a sort of Byzantine feudal contract in which tracts of land (or the tax revenue from it) were granted to particular individuals in exchange for contributing to and maintaining military forces.[10][78]

Arts and culture

In the years 1042–1050, Constantine kept a small group of intellectuals in his inner circle, including Michael Psellos, John Mauropous, John Xiphilinus, and Constantine Leichoudes. These men, especially Psellos, were the leading lights of the Macedonian Renaissance, and their role in governance has sometimes been called the "Philosophers' regime".[79]

After the disintegration of this governmental clique following the death of Zoë, Psellos continued in the philosophy department of the university, leading an intellectual movement that advocated for returning to ancient Greek and even Neoplatonic philosophy.[80] Other intellectual currents of the time include the reception of the mystical teachings of St Symeon the New Theologian following his canonization and the new poetry of Christopher of Mytilene.

The material arts continued to thrive under Constantine IX and the empire economic prosperity. Psellos's Chronographia records the marvelous gardens of the Mangana complex.[81] Constantine had himself depicted in mosaic on the walls of the Hagia Sophia and in the Cloisonné enamel-work of the Monomachus Crown.

See also

Notes

References

- ^ Davies, Wendy; Fouracre, Paul (2 September 2010). The Languages of Gift in the Early Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press. p. 38. ISBN 9780521515177.

The mosaic dates between 1042, when Zoe married Constantine (her third husband), and 1050, when Zoe died, but the heads have been changed and the mosaic probably originally portrayed Zoe with her first husband, Romanos III (1028–34), who also donated funds to the church.

- ^ Kaldellis, Anthony (2023). The New Roman Empire: A History of Byzantium. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 922. ISBN 978-0197549322.

1042–1055 Konstantinos IX Monomachos (marries Zoe 1042–1050?, and with her sister Theodora)

- ^ A.V. Soloviev, 'Marie, fille de Constantin IX Monomaque', Byzantion, vol. 33, 1963, p. 241-248.

- ^ a b "Constantine IX Monomachus". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Head, Constance (1982). Imperial Byzantine Portraits: A Verbal and Graphic Gallery. Caratzas Brothers Publishing. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-89241-084-2.

- ^ a b Kazhdan, pg. 1398

- ^ Norwich, pg. 307

- ^ Eric Limousin. Constantin IX Monomaque : empereur ou homme de réseau ?. 140 e Congrès national des sociétés historiques et scientifiques, May 2015, Reims, France. p. 26-37.

- ^ a b Norwich, pg. 306

- ^ a b Kazhdan, pg. 504

- ^ Finlay, pg. 500

- ^ Finlay, pg. 499

- ^ Georgius Cedrenus − CSHB 9: 540-2: "Michaelus in monasterium Elegmorum, 21 die Aprilis... Augusta Zoe nupsit... die Iunii undecima anni eius quem supra indicavimus. postridie coronatus est a patriarcha."

- ^ a b Hatzaki, Myrto (2009). Beauty and the Male Body in Byzantium: Perceptions and Representations in Art and Text. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-230-24530-3.

- ^ Oikonomides, Nicolas (1978). "The Mosaic Panel of Constantine IX and Zoe in Saint Sophia". Revue des études byzantines. 36 (1): 219–232. doi:10.3406/rebyz.1978.2086.

- ^ Nathan, Geoffrey; Garland, Lynda (1 January 2011). Basileia: Essays on Imperium and Culture in Honour of E.M. and M.J. Jeffreys. BRILL. p. 187. ISBN 978-90-04-34489-1.

- ^ Norwich, pg. 308

- ^ Finlay, pg, 510

- ^ Finlay, pg. 505

- ^ Kaldellis 2017, p. 181.

- ^ Norwich, pg. 309

- ^ a b Angold 1997, p. 49.

- ^ Norwich, pg. 310

- ^ a b Norwich, pg. 311

- ^ Kaldellis 2017, p. 186.

- ^ Finlay, pg. 514

- ^ Christian Settipani, Continuité des élites à Byzance durant les siècles obscurs. Les princes caucasiens et l'Empire du vie au ixe siècle, Paris, de Boccard, 2006, p. 245. (ISBN 978-2-7018-0226-8)

- ^ A.V. Soloviev, 'Marie, fille de Constantin IX Monomaque', Byzantion, vol. 33, 1963, p. 241-248.

- ^ P.P Tolocko, Byzance vue par les Russes, dans Le sacré et son inscription dans l'espace à Byzance et en Occident, Publications de la Sorbonne, 2001, pp. 277-284.

- ^ Norwich, pg. 309

- ^ Finlay, pg. 503

- ^ Norwich, pg. 340

- ^ a b Norwich, pg. 341

- ^ Finlay, pg. 520

- ^ Laiou, pg. 3, 693

- ^ al-Zubayr, Aḥmad ibn al-Rashīd Ibn (1996). Book of Gifts and Rarities. Harvard CMES. pp. 109–110, 296. ISBN 978-0-932885-13-5.

- ^ Angold 1997, pp. 37–40.

- ^ Kaldellis 2017, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Angold 1997, p. 59.

- ^ Kaldellis 2017, p. 193.

- ^ Bréhier, pg. 325

- ^ Norwich, pg. 312

- ^ Angold 1997, p. 60.

- ^ Kaldellis 2017, p. 194–195.

- ^ Norwich, pg. 314

- ^ Finlay, pg. 515

- ^ Angold 1997, p. 38–39.

- ^ Norwich, pg. 315

- ^ Kaldellis 2017.

- ^ Garland 1999, pp. 165, 230.

- ^ Kaldellis 2017, p. 201.

- ^ Angold 1997, p. 82.

- ^ a b c Treadgold 1997, p. 595.

- ^ Angold 1997, p. 82–83.

- ^ Kaldellis 2017, pp. 210–211.

- ^ Kaldellis 1997, p. 211.

- ^ Kaldellis 2017, p. 205.

- ^ Angold 1997, p. 52.

- ^ Norwich, pg. 321

- ^ Norwich, pg. 316

- ^ Skylitzes, John (1973) [1057] Synopsis of Histories, 478, n.92 (Bekker 610, s.18). "ιαʹ του Ιανουαρίου."

- ^ For the date 7 / 8 January, see: Peter Schreiner (1977). Kleinchroniken 2., 148 (cf. Kleinchroniken 1)

- ^ Finlay, pg. 527

- ^ Treadgold, pg. 596

- ^ Angold 1997, p. 95.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, p. 591.

- ^ Kaldellis 2017, p. 189.

- ^ Angold 1997, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Kaldellis 2017, p. 190.

- ^ Angold 1997, pp. 63–64.

- ^ John H. Rosser, Historical Dictionary of Byzantium, Scarecrow Press, 2001, p. xxx.

- ^ Aleksandr Petrovich Kazhdan, Annabel Jane Wharton, Change in Byzantine Culture in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries, University of California Press, 1985, p. 122.

- ^ Angold 1997, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Kaldellis 2017, p. 188.

- ^ Finlay, pg. 468

- ^ Ousterhout, Robert (1989). "Rebuilding the Temple: Constantine Monomachus and the Holy Sepulchre". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 48 (1): 66–78. doi:10.2307/990407. JSTOR 990407.

- ^ Angold 1997, p. 79.

- ^ Finlay, pg. 504

- ^ Kaldellis 2017, p. 191.

- ^ Wilson, Nigel (31 October 2013). Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece. Routledge. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-136-78800-0.

- ^ Littlewood, Antony Robert; Maguire, Henry; Wolschke-Bulmahn, Joachim (2002). Byzantine Garden Culture. Dumbarton Oaks. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University. p. 63.

Sources

Primary sources

- Michael Psellus, Fourteen Byzantine Rulers, trans. E.R.A. Sewter (Penguin, 1966). ISBN 0-14-044169-7

- Thurn, Hans, ed. (1973). Ioannis Scylitzae Synopsis historiarum. Berlin-New York: De Gruyter. ISBN 9783110022858.

Secondary sources

- Angold, Michael (1997). The Byzantine Empire, 1025-1204: A Political History (2nd ed.). New York: Longman. ISBN 0-582-29468-1.

- Blaum, Paul A. (2004). "Diplomacy Gone to Seed: A History of Byzantine Foreign Relations, A.D. 1047-57". International Journal of Kurdish Studies. 18 (1): 1–56.

- Bréhier, Louis (1946). Le monde byzantin: Vie et mort de Byzance (PDF) (in French). Paris, France: Éditions Albin Michel. OCLC 490176081.

- Finlay, George. History of the Byzantine Empire from 716 – 1057, William Blackwood & Sons, 1853.

- Garland, Lynda. Conformity and Non-conformity in Byzantium, Verlag Adolf M. Hakkert, 1997. ISBN 978-9-02560-619-0

- Garland, Lynda (1999). Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium, AD 527–1204. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-14688-3.

- Harris, Jonathan. Constantinople: Capital of Byzantium (Hambledon/Continuum, 2007). ISBN 978-1-84725-179-4

- Jeffreys, Michael, ed. (2016). "Konstantinos IX Monomachos". Prosopography of the Byzantine World. King's College London. ISBN 978-1-908951-20-5.

- Kaldellis, Anthony (2017). Streams of Gold, Rivers of Blood: The Rise and Fall of Byzantium, 955 A.D. to the First Crusade. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1902-5322-6.

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991), "Constantine IX Monomachos", Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6

- Laiou, Angeliki E. (2002). The Economic History of Byzantium: From the Seventh through the Fifteenth Century. Dumbarton Oaks Stidies XXXIX. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 0-88402-288-9.

- Norwich, John Julius (1993), Byzantium: The Apogee, Penguin, ISBN 0-14-011448-3

- Treadgold, Warren T. (1997), A History of the Byzantine State and Society, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-2630-2