| History of England |

|---|

|

|

|

Anglo-Saxon England or early medieval England covers the period from the end of Roman imperial rule in Britain in the 5th century until the Norman Conquest in 1066. Compared to modern England, the territory of the Anglo-Saxons stretched north to present day Lothian in southeastern Scotland, whereas it did not initially include western areas of England such as Cornwall, Herefordshire, Shropshire, Cheshire, Lancashire, and Cumbria.

The 5th and 6th centuries involved the collapse of economic networks and political structures, and also saw a radical change to a new Anglo-Saxon language and culture. This change was driven not only by movements of peoples, but also by changes which were happening in both northern Gaul, and the North Sea coast of what is now Germany and the Netherlands. The Ango-Saxon language itself, also known as Old English, was a close relative of languages spoken in the latter regions, and genetic studies have confirmed that there was significant migration to Britain from there starting already before the end of the Roman period. Surviving written accounts suggest that Britain was divided into small "tyrannies" which initially still took their bearings to some extent from Roman norms.

By the late 6th century England was dominated by small kingdoms ruled by dynasties who were pagan, and identified themselves as having differing continental ancestries. A smaller number of kingdoms maintained a British and Christian identity but by this time they were restricted to the west of Britain. The most important Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in the 5th and 6th centuries are conventionally called a Heptarchy, meaning a group of seven kingdoms, although the number of kingdoms varied over time. The most powerful included Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Sussex, and Wessex. During the 7th century the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were converted to Christianty by missionaries from both Ireland and the continent.

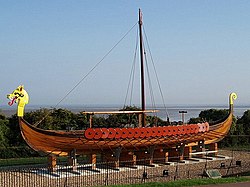

In the 8th century, Vikings began raiding England, and by the second half of the 9th century Scandinavians began to settle in eastern England. Opposing the Vikings from the south, the royal family of Wessex gradually became dominant, and in 927 AD King Æthelstan I (reigned 927–939) was the first king to rule a single united Kingdom of England. After his death however, the Danish settlers and other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms reasserted themselves. Wessex agreed to pay the so-called Danegeld to the Danes, and in 1017 England became part of the North Sea Empire of Cnut, a personal union between England, Denmark and Norway. After Cnut's death in 1035, England was ruled first by his son Harthnacnut, but then succeeded by his English half-brother Edward the Confessor. Edward had been forced to lived in exile, and when he died in 1066, one of the claimants to the thrown was William, the Duke of Normandy.

The Anglo-Saxon period ends with the Norman Conquest of England by William the Conqueror in 1066. The Normans persecuted the Anglo-Saxons and overthrew their ruling class to substitute their own leaders to oversee and rule England.[1] However, Anglo-Saxon identity survived beyond the Norman Conquest,[2] came to be known as Englishry under Norman rule, and through social and cultural integration with Romano-British Celts, Danes and Normans became the modern English people.

Terminology

In modern times, the term "Anglo-Saxons" is used by scholars to refer collectively to the Old English speaking groups in Britain. As a compound term, it covers the various English-speaking groups on the one hand, and also avoids possible misunderstandings which could come from using the terms "Saxons" or "Angles" (English), both of which terms could be used either as collectives referring to all the Old English speakers, or to specific tribal groups. Although the term "Anglo Saxon" was not used as a common term until modern times, it is not a modern invention because it was also used in some specific contexts already between the 8th and 10th centuries.

Before the 8th century, the most common collective term for the Old-English speakers was "Saxons", which was a word originally associated since the 4th century not with a specific country or nation, but with raiders in North Sea coastal areas of Britain and Gaul. An especially early reference to the Angli is the 6th-century Byzantine historian Procopius who heard through Frankish diplomats that an island called Brittia, lieing not far from the mouth of the Rhine, was settled by three nations: the Angili, Frissones, and Brittones, each ruled by its own king. (He did not use the word Saxon at all.)[3]

By the 8th century the Saxons in Germany were seen as a distinct country, and writers such as Bede and some of his contemporaries including Alcuin, and Saint Boniface, began to refer to the overall group in Britain as the "English" people (Latin Angli, gens Anglorum or Old English Angelcynn). In Bede's work the term "Saxon" is also used to refer sometimes to the Old English language, and also to refer to the early pagan Anglo-Saxons before the arrival of Christian missionaries among the Anglo-Saxons of Kent in 597.[4] To distinguish them, Bede called the pagan Saxons of the mainland the "Old Saxons" (antiqui saxones).

Similarly, a non-Anglo-Saxon contemporary of Bede, Paul the Deacon, referred variously to either the English (Angli), or Anglo-Saxons (Latin plural genitives Saxonum Anglorum, or Anglorum Saxonum), which helped him distinguish them from the European Saxons who he also discussed. In England itself this compound term also came to be used in some specific situations, both in Latin and Old English. Alfred the Great, himself a West Saxon, was for example Anglosaxonum Rex in the late 880s, probably indicating that he was literally a king over both English (for example Mercian) and Saxon kingdoms. However, the term "English" continued to be used as a common collective term, and indeed became dominant. The increased use of these new collective terms, "English" or "Anglo-Saxon", represents the strengthening of the idea of a single unifying cultural unity among the Anglo-Saxons themselves, who had previously invested in identities which differentiated various regional groups.[4]

The historian James Campbell suggested that it was not until the late Anglo-Saxon period that England could be described as a nation-state.[5] It is certain that the concept of "Englishness" only developed very slowly.[6][7]

End of Roman era and Anglo-Saxon origins

The Anglo-Saxon period begins with the end of Roman rule in the 5th century AD, but the details of this transition are unclear. Already in the late 4th century, during Roman rule, the archaeological record shows signs of economic collapse, not only in Britain, but also in Roman northern Gaul, and in present day northern Germany. By 430 AD a radical cultural change is evident in Britain, affecting for example burial styles, building styles and clothing. Both the archaeological evidence and genetic findings indicate that these changes were influenced to at least some extent by immigrants who were coming from the North Sea coasts of what is now the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark, but some of the changes also have parallels with northern Gaul, which was similarly a country where Roman forces and government were weakening or being withdrawn.[8] Usage of the distinctive Anglo-Saxon language, Old English can't be proven during this period, but its closest relatives were the Old Frisian and Old Saxon dialects of the same continental coastal regions, and so some amount of migration is once again implied.

While there is a tradition of seeing the Anglo-Saxon language and culture as something imported suddenly, only after the collapse of Roman rule, Germanic soldiers from areas near the Rhine delta had been brought to Britain since the beginnings of Roman rule in Britain in 43 AD, and may have already been a significant presence in Roman society. The written record agrees with the genetic evidence that such movements of people increased already before the end of Roman rule. The term "Saxon" only began to be used by Roman authors in the 4th century, initially to refer to Germanic raiders from areas north of the Frankish tribes who lived closest to the Rhine delta. 4th century Roman sources reported that these Saxons had been troubling the coasts of the North Sea and English channel since the late 3rd century.[9] Among the earliest such mentions of Saxons, they were named as allies of the rebel emperors Carausius, who was based in Britain, and Magnentius.[10]

At some point in the third or fourth centuries the Romans also established a military commander who was assigned to oversee a chain of coastal forts on both sides of the channel and the one on the British side was called the Saxon shore (Litus Saxonicum).[11]

According to the fourth century historian Ammianus Marcellinus, in 367 the Romano-British defences were overrun by Scoti from Ireland, Picts from northern Scotland, together with Saxons in the so-called Barbarian Conspiracy. In 368 AD imperial forces under the command of Count Theodosius defeated Saxons who were apparently based in Britain, and coordinating with the Scoti and Picts.[12] In 382 Magnus Maximus defeated another invasion by Picts and Scoti, but in the following year he led an army to Gaul for a bid to become emperor. There were further troop withdrawals in the 390s and the last major import of coins to pay the troops took place around 400, after which the army was not paid.[13][14]

The early Christian Berber author, Tertullian, writing in the 3rd century, said that "Christianity could even be found in Britain".[15] The Roman Emperor Constantine (306–337) granted official tolerance to Christianity with the Edict of Milan in 313. Christianity had been introduced into the British Isles during the Roman occupation. Then, in the reign of Emperor Theodosius "the Great" (379–395), Christianity was made the official religion of the Roman Empire.[a][17]

It is not entirely clear how many Britons would have been Christian when the pagan Anglo-Saxons arrived.[b][19] There had been attempts to evangelise the Irish by Pope Celestine I in 431.[20] However, it was Saint Patrick who is credited with converting the Irish en masse.[20] A Christian Ireland then set about evangelising the rest of the British Isles, and Columba founded a religious community in Iona, off the west coast of Scotland.[21] Then Aidan was sent from Iona to set up his see in Northumbria, at Lindisfarne, between 635 and 651.[22] Hence Northumbria was converted by the Celtic (Irish) church.[22]

Rapid cultural change (400–550 AD)

The last Roman ruler of Britain, the self-proclaimed emperor Constantine III (reign 407-411), moved Roman forces based in Britain to the continent. The Romano-British citizens reportedly expelled their Roman officials during this period, and never again re-joined the Roman empire.[23] Apparently taking advantage of the lack of organized military, the Chronica Gallica of 452 reports that Britain was ravaged by Saxon invaders in 409 or 410. Writing in the mid-sixth century, Procopius stated that after the overthrow of Constantine III in 411, "the Romans never succeeded in recovering Britain, but it remained from that time under tyrants".[24]

The Romano-Britons nevertheless called upon the empire to help them fend off attacks from not only the Saxons, but also the Picts and Scoti. A hagiography of Saint Germanus of Auxerre claims that he helped command a defence against an invasion of Picts and Saxons in 429. By about 430 the archaeological record in Britain begins to indicate a relatively rapid melt-down of Roman material culture, and its replacement by a new material culture associated with the Anglo-Saxons. The Chronica Gallica of 452 records for the year 441: "The British provinces, which to this time had suffered various defeats and misfortunes, are reduced to Saxon rule." Gildas, writing some generations later, reported that at some time between 445 and 454 the Britons wrote to the Roman military leader Aëtius in Gaul, begging for assistance, with no success.

This having failed, Gildas reports that an un-named Romano-British "proud tyrant" invited "Saxons" to Britain to help defend Britain from the Picts and Scoti, working under a Roman-style military treaty as foederati, which entitled them to lands in Britain. According to Gildas, these Saxons came into conflict with the Romano-British rulers when they were not given sufficient monthly supplies. In reaction to this they overran the whole country, and then returned to their home area.[25] After this, the British united successfully under Ambrosius Aurelianus, and struck back. Historian Nick Higham calls this the "War of the Saxon Federates". It ended after a Romano-British victory at the siege at "Mount Badon", the location of which is no longer known.[26] Writing generations later Gildas, unlike much later Anglo Saxon writers, didn't mention any ongoing conflict against "Saxons". Instead of wars against foreigners he complained that the country was now divided into small kingdoms which fought amongst each other, and impeded safe travel around the country.

Centuries later, Anglo-Saxon writers, in contrast, saw the events described by Gildas as the beginning of a massive movement of people from northern Europe, an account which influences historians to this day. In Bede's account the call to the "Angle or Saxon nation" (Latin: Anglorum sive Saxonum gens) was initially answered by three boats led by two brothers, Hengist and Horsa ("Stallion and Horse"), and Hengist's son Oisc. Some modern scholars have suggested that both "Hengist" and Oisc may both represent memories of the same person as Ansehis, who was named in the Ravenna Cosmography as the chief of the "Old Saxons" who led his people to Britain, almost emptying his country.[27] Bede believed that that the region these Saxons had assigned to them was in the eastern part of Britain.[28] As to their origin, Bede named pagan peoples still living in Germany (Germania) in the eighth century "from whom the Angles or Saxons, who now inhabit Britain, are known to have derived their origin; for which reason they are still corruptly called "Garmans" by the neighbouring nation of the Britons": the Frisians, the Rugini (possibly from Rügen), the Danes, the "Huns" (Pannonian Avars in this period, whose influence stretched north to Slavic-speaking areas in central Europe), the "old Saxons" (antiqui Saxones), and the "Boructuari" who are presumed to be inhabitants of the old lands of the Bructeri, near the Lippe river.[29] Bede believed the country of the Angli themselves had been emptied because of these migrations.

With regards to this specific Saxon conflict reported by Gildas, modern historians remain uncertain about its timing, and the relative importance it had in terms of its effect on the overall culture or population, which began changing rapidly already in the late 4th century. More generally, scholars continue to debate the timing and size of migrations from the continental North Sea coast. A traditional account of sudden Anglo-Saxon immigration, and forced displacement or decimation of local populations has been influential since at least the eighth century retelling of the Gildas account by the Anglo-Saxon historian Bede the Venerable. In this traditional account, these events were the beginning of a massive and violent invasion of Anglo Saxons into Britain after the end of Roman rule in 411 AD. The arrival of the soldiers described by Gildas became the adventus saxonum representing the main immigration event, which was followed by a period where small, pagan Anglo Saxon kingdoms in the east fought small Christian British kingdoms in the west, and bit by bit the Anglo Saxons defeated the British and took over a large part of Britain by force, creating England. In this traditional account ethnic Anglo-Saxons and ethnic Britons were distinct and separated peoples, conscious of the war between their nations. It was envisioned that British people living in Anglo-Saxon kingdoms either had to move, or else convert to a foreign culture.[30]

Modern scholars however generally believe that Germanic-speakers started arriving in Britain already long before the end of Roman rule, probably mainly as soldiers. They may have already formed a significant part of Romano-British society at the end of Roman rule, and their culture probably continued to be especially associated with the military. That immigration and conflict involving Germanic-speakers increased during the 5th century, after the end of Roman rule, is still widely accepted by scholars, but it is no longer assumed that this necessarily involved the immediate formation of small Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, or a straightforward conflict between two opposed ethnic groups. Such ethnic kingdoms were known to Bede from his own time, but much uncertainty remains about the way in which these kingdoms developed between the time of Gildas and the time of Bede.[31]

A 2022 genetic study used modern and ancient DNA samples from England and neighbouring countries to study the question of physical Anglo-Saxon migration and concluded that there was large-scale immigration of both men and women into Eastern England, from a "north continental" population matching early medieval people from the area stretching from northern Netherlands through northern Germany to Denmark. This began already in the Roman era, and then increased rapidly in the 5th century. The burial evidence showed that the locals and immigrants were being buried together using the same new customs, and that they were having mixed children. The authors estimate the effective contributions to modern English ancestry are between 25% and 47% "north continental", 11% and 57% from British Iron Age ancestors, and 14% and 43% was attributed to a more stretched-out migration into southern England, from nearby populations such as modern Belgium and France. There were significant regional variations in north continental ancestry ― lower in the west, and highest in Sussex, the East Midlands and East Anglia.[32]

Origin of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms

There is no clear evidence concerning the origins of the later Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. The main evidence comes from later Anglo-Saxon literature beginning in the 8th century, which indicates that there were many small kingdoms existing by the 7th century, not only on the coast, but also inland. The traditional account of their origins is influenced by these Anglo-Saxon sources and sees the kingdoms as having been ethnically distinct from their beginnings, and initially based on the southern and eastern coasts only. In a process that has been called an "FA cup model" these kingdoms are traditionally assumed to have started small, and then gradually merged to a smaller number of larger kingdoms. One traditional term used for this period, the heptarchy, suggests the existence of seven dominant kingdoms. In fact the number of kingdoms and sub-kingdoms fluctuated during this period as competing kings contended for supremacy.[33]

Bede in the 8th century, reported the genealogical claims of the dynasties ruling the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of their own time. In the semi-mythical account of Bede a bigger fleet followed the Saxons reported by Gildas, representing the three most powerful tribes of Germania, the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, and these were eventually followed by terrifying swarms. The naming of these three specific tribes was probably influenced by the semi-mythological genealogical claims of the royal families of Bede's time. In a well-known passage, Bede gave a rough description of the homelands of these three peoples, and described the places in Britain where he believed they had settled:[34]

- The Saxons came from what Bede called Old Saxony, and created the kingdoms of Wessex, Sussex and Essex, which have names meaning "West Saxons", "South Saxons", and "East Saxons".

- Jutland, [c] On the peninsula containing part of what is now modern Denmark, according to Bede was the homeland of the Jutes who he saw as ancestors of the royal families of Kent and the Isle of Wight.

- The Angles (or English) were from "Anglia", a country which Bede understood to have become empty due to emigration. It lay between the homelands of the Saxons and Jutes. Anglia is usually interpreted as being near the old Schleswig-Holstein Province (straddling the modern Danish-German border), and containing the modern Angeln. (Bede also used the term English as a collective term for the Anglo-Saxons of his time.)

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, written in the 9th century, reports that the various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms which eventually merged to become England were founded when small fleets of three or five ships of invaders arrived at various points around the coast of England to fight the sub-Roman British, and conquered their lands.[d]

The four most important kingdoms at first in Anglo-Saxon England were East Anglia, Mercia, Northumbria (originally two kingdoms, Bernicia and Deira), and Wessex (originally known as the Gewisse, and apparently based inland near the Thames). Minor kingdoms included Essex, Kent, and Sussex. Other minor kingdoms and territories are mentioned in sources such as the Tribal Hideage. The Anglo Saxon Chronicle also used the term Bretwalda to refer to kings who held a dominant position over other kings in southern England, south of the Humber. The first such bretwalda that the Anglo Saxon Chronicle named was Ælle of Sussex, who the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes as living in the 5th century, but accounts of this early king and his three sons are considered doubtful by modern scholars.

"Heptarchy" and Christianisation (550-800 AD)

The second bretwalda named by the Anglo Saxon Chronicle , Ceawlin, was king of the Gewisse in the second half of the 6th century, and an ancestor to the kings of Wessex. He expanded his kingdom at the expense of British kingdoms, taking Cirencester, Gloucester and Bath as a result of the Battle of Dyrham.[37][38][39] This expansion of Wessex ended abruptly when the Anglo-Saxons started fighting among themselves, resulting in Ceawlin retreating to his original territory. He was then replaced by Ceol, who was possibly his nephew. Ceawlin was killed the following year, but the annals do not specify by whom.[40][41] Modern scholars note that Ceawlin's name, and the names of some of his reported relatives, appear to be British rather than Germanic, throwing doubt upon the assertion that his family arrived from the continent with five boats, as reported in the Anglo Saxon Chronicle.

King Æthelberht of Kent was later seen by the Anglo Saxon Chronicle as the third bretwalda south of the Humber.[42] Æthelberht's law for Kent, the earliest written code in any Germanic language, instituted a complex system of fines. Kent was rich, with strong trade ties to the continent, and Æthelberht may have instituted royal control over trade. For the first time following the Anglo-Saxon invasion, coins began circulating in Kent during his reign. His son-in-law Sæberht of Essex also converted to Christianity.

In 595 Augustine landed on the Isle of Thanet in Kent and proceeded to King Æthelberht's main town of Canterbury. He had been sent by Pope Gregory the Great to lead the Gregorian mission to Britain to Christianise the Kingdom of Kent from their native Anglo-Saxon paganism. Kent was probably chosen because Æthelberht had married a Christian princess, Bertha, daughter of Charibert I the king of Paris, who was expected to exert some influence over her husband. Augustine was given land by King Æthelberht of Kent to build a church; so in 597 Augustine built the church and founded the See at Canterbury.[43] Æthelberht was baptised by 601, and he then continued with his mission to convert the English.[44]

After Æthelberht's death in about 616/618, the 4th bretwalda according to the Anglo Saxon Chronicle was Rædwald of East Anglia, who also gave Christianity a foothold in his kingdom, and helped to install Edwin of Northumbria, who replaced Æthelfrith to become the second king over the two kingdoms north of the Humber, Bernicia and Deira. After Rædwald died, Edwin was able to pursue a grand plan to expand Northumbrian power.[45] The Anglo Saxon Chronicle lists him as the 5th bretwalda. The growing strength of Edwin of Northumbria forced the Anglo-Saxon Mercians of King Penda into an alliance with the Welsh king Cadwallon ap Cadfan of Gwynedd, and together they invaded Edwin's lands and defeated and killed him at the Battle of Hatfield Chase in 633.[46][47] Their success was short-lived, as Oswald, one of the sons of the late King of Northumbria, Æthelfrith, defeated and killed Cadwallon at Heavenfield near Hexham.[48] Oswald subsequently became the third king of Northumbria, and is listed by the Anglo Saxon Chronicle as the 6th bretwalda.

In 635, Aidan, an Irish monk from Iona, chose the Isle of Lindisfarne to establish a monastery which was close to King Oswald's main fortress of Bamburgh. He had been at the monastery in Iona when Oswald asked to be sent a mission to Christianise the Kingdom of Northumbria from their native Anglo-Saxon paganism. Oswald had probably chosen Iona because after his father had been killed he had fled into south-west Scotland and had encountered Christianity, and had returned determined to make Northumbria Christian. Aidan achieved great success in spreading the Christian faith in the north, and since Aidan could not speak English and Oswald had learned Irish during his exile, Oswald acted as Aidan's interpreter when the latter was preaching.[49] Later, Northumberland's patron saint, Saint Cuthbert, was an abbot of the monastery, and then Bishop of Lindisfarne. An anonymous life of Cuthbert written at Lindisfarne is the oldest extant piece of English historical writing,[e] and in his memory a gospel (known as the St Cuthbert Gospel) was placed in his coffin. The decorated leather bookbinding is the oldest intact European binding.[51]

There was friction between the followers of the Roman rites and the Irish rites, particularly over the date on which Easter fell and the way monks cut their hair.[52] In 664, a conference was held at Whitby Abbey (known as the Whitby Synod) to decide the matter; Saint Wilfrid was an advocate for the Roman rites and Bishop Colmán for the Irish rites.[53] Wilfrid's argument won the day and Colmán and his party returned to Ireland in their bitter disappointment.[53] The Roman rites were adopted by the English church.[53][54]

Less than a decade after his defeat Penda again waged war against Northumbria, and killed Oswald in the Battle of Maserfield in 642.[55] Oswald's brother Oswiu was chased to the northern extremes of his kingdom.[55][56] Although not included in the Anglo Saxon Chronicle list of bretwaldas Penda was the dominant king of the English until he was himself killed in battle against Oswald's brother Oswiu in 655. Oswiu, Bede's 7th bretwalda, remained the dominant king of England until he died in 670.

The kingdom of Mercia continued its conflict with the Welsh kingdom of Powys in the 8th century.[55] This conflict reached its climax during the reign of Offa of Mercia (reigned 757-796),[55] who is remembered for the construction of a 150-mile-long dyke which formed the Wales/England border.[57] It is not clear whether this was a boundary line or a defensive position.[57] By the middle of the 8th century, other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of southern Britain were also affected by Mercian expansionism. The East Saxons seem to have lost control of London, Middlesex and Hertfordshire to Æthelbald, although the East Saxon homelands do not seem to have been affected, and the East Saxon dynasty continued into the ninth century.[58]

The ascendency of Wessex and the Vikings (9th century)

The ascendency of the Mercians came to an end in 825, when they were soundly beaten under Beornwulf at the Battle of Ellendun by Egbert of Wessex, who is the 8th and last bretwalda listed by the Anglo Saxon Chronicle.[59]

During the 9th century, Wessex rose in power, from the foundations laid by King Egbert in the first quarter of the century to the achievements of King Alfred the Great in its closing decades. The outlines of the story are told in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, though the annals represent a West Saxon point of view.[60] On the day of Egbert's succession to the kingdom of Wessex, in 802, a Mercian ealdorman from the province of the Hwicce had crossed the border at Kempsford, with the intention of mounting a raid into northern Wiltshire; the Mercian force was met by the local ealdorman, "and the people of Wiltshire had the victory".[61] In 829, Egbert went on, the chronicler reports, to conquer "the kingdom of the Mercians and everything south of the Humber".[62] It was at this point that the chronicler chooses to attach Egbert's name to Bede's list of seven overlords, adding that "he was the eighth king who was Bretwalda".[63] Simon Keynes suggests Egbert's foundation of a 'bipartite' kingdom is crucial as it stretched across southern England, and it created a working alliance between the West Saxon dynasty and the rulers of the Mercians.[64] In 860, the eastern and western parts of the southern kingdom were united by agreement between the surviving sons of King Æthelwulf, though the union was not maintained without some opposition from within the dynasty.

From 874 to 879, the western half of Mercia was ruled by Ceowulf II, who was succeeded by Æthelred as Lord of the Mercians.[65] In the late 870s King Alfred gained the submission of the Mercians under their ruler Æthelred, who in other circumstances might have been styled a king, but who under the Alfredian regime was regarded as the 'ealdorman' of his people.

The wealth of the monasteries and the success of Anglo-Saxon society attracted the attention of people from mainland Europe, mostly Danes and Norwegians. Because of the plundering raids that followed, the raiders attracted the name Viking – from the Old Norse víkingr meaning an expedition – which soon became used for the raiding activity or piracy reported in western Europe.[66] In 793, Lindisfarne was raided and while this was not the first raid of its type it was the most prominent. In 794, Jarrow, the monastery where Bede wrote, was attacked; in 795 Iona in Scotland was attacked; and in 804 the nunnery at Lyminge in Kent was granted refuge inside the walls of Canterbury. Sometime around 800, a Reeve from Portland in Wessex was killed when he mistook some raiders for ordinary traders.

Between the 8th and 11th centuries, raiders and colonists from Scandinavia, mainly Danish and Norwegian, plundered western Europe, including the British Isles.[67] These raiders came to be known as the Vikings; the name is believed to derive from Scandinavia, where the Vikings originated.[68][69] The first raids in the British Isles were in the late 8th century, mainly on churches and monasteries (which were seen as centres of wealth).[68][70] The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports that the holy island of Lindisfarne was sacked in 793.[71] The raiding then virtually stopped for around 40 years; but in about 835, it started becoming more regular.[72]

In the 860s, instead of raids, the Danes mounted a full-scale invasion. In 865, an enlarged army arrived that the Anglo-Saxons described as the Great Heathen Army. This was reinforced in 871 by the Great Summer Army.[72] Within ten years nearly all of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms fell to the invaders: Northumbria in 867, East Anglia in 869, and nearly all of Mercia in 874–77.[72] Kingdoms, centres of learning, archives, and churches all fell before the onslaught from the invading Danes. Only the Kingdom of Wessex was able to survive.[72] In March 878, the Anglo-Saxon King of Wessex, Alfred, with a few men, built a fortress at Athelney, hidden deep in the marshes of Somerset.[74] He used this as a base from which to harry the Vikings. In May 878 he put together an army formed from the populations of Somerset, Wiltshire, and Hampshire, which defeated the Viking army in the Battle of Edington.[74] The Vikings retreated to their stronghold, and Alfred laid siege to it.[74] Ultimately the Danes capitulated, and their leader Guthrum agreed to withdraw from Wessex and to be baptised. The formal ceremony was completed a few days later at Wedmore.[74][75] There followed a peace treaty between Alfred and Guthrum, which had a variety of provisions, including defining the boundaries of the area to be ruled by the Danes (which became known as the Danelaw) and those of Wessex.[76] The Kingdom of Wessex controlled part of the Midlands and the whole of the South (apart from Cornwall, which was still held by the Britons), while the Danes held East Anglia and the North.[77]

After the victory at Edington and resultant peace treaty, Alfred set about transforming his Kingdom of Wessex into a society on a full-time war footing.[78] He built a navy, reorganised the army, and set up a system of fortified towns known as burhs. He mainly used old Roman cities for his burhs, as he was able to rebuild and reinforce their existing fortifications.[78] To maintain the burhs, and the standing army, he set up a taxation system known as the Burghal Hidage.[79] These burhs (or burghs) operated as defensive structures. The Vikings were thereafter unable to cross large sections of Wessex: the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports that a Danish raiding party was defeated when it tried to attack the burh of Chichester.[80][81]

Although the burhs were primarily designed as defensive structures, they were also commercial centres, attracting traders and markets to a safe haven, and they provided a safe place for the king's moneyers and mints.[82] A new wave of Danish invasions commenced in 891,[83] beginning a war that lasted over three years.[84][85] Alfred's new system of defence worked, however, and ultimately it wore the Danes down: they gave up and dispersed in mid-896.[85]

Alfred is remembered as a literate king. He or his court commissioned the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which was written in Old English (rather than in Latin, the language of the European annals).[86] Alfred's own literary output was mainly of translations, but he also wrote introductions and amended manuscripts.[86][87]

From 874 to 879, the western half of Mercia was ruled by Ceowulf II, who was succeeded by Æthelred as Lord of the Mercians.[65]

Alfred the Great of Wessex styled himself King of the Anglo-Saxons from about 886. In 886/887 Æthelred married Alfred's daughter Æthelflæd.[65] On Alfred's death in 899, his son Edward the Elder succeeded him.[88]

English unification (10th century)

When Æthelred died in 911, Æthelflæd succeeded him as "Lady of the Mercians",[65] and in the 910s she and her brother Edward recovered East Anglia and eastern Mercia from Viking rule.[65] Edward and his successors expanded Alfred's network of fortified burhs, a key element of their strategy, enabling them to go on the offensive.[89][90] When Edward died in 924 he ruled all England south of the Humber. His son, Æthelstan, annexed Northumbria in 927 and thus became the first king of all England. At the Battle of Brunanburh in 937, he defeated an alliance of the Scots, Danes, Vikings and Strathclyde Britons.[89]

During the course of the 10th century, the West Saxon kings extended their power first over Mercia, then into the southern Danelaw, and finally over Northumbria, thereby imposing a semblance of political unity on peoples, who nonetheless would remain conscious of their respective customs and their separate pasts. The prestige, and indeed the pretensions, of the monarchy increased, the institutions of government strengthened, and kings and their agents sought in various ways to establish social order.[91] This process started with Edward the Elder – who with his sister, Æthelflæd, Lady of the Mercians, initially, charters reveal, encouraged people to purchase estates from the Danes, thereby to reassert some degree of English influence in territory which had fallen under Danish control. David Dumville suggests that Edward may have extended this policy by rewarding his supporters with grants of land in the territories newly conquered from the Danes and that any charters issued in respect of such grants have not survived.[92] When Athelflæd died, Mercia was absorbed by Wessex. From that point on there was no contest for the throne, so the house of Wessex became the ruling house of England.[91]

Edward the Elder was succeeded by his son Æthelstan, whom Keynes calls the "towering figure in the landscape of the tenth century".[93] His victory over a coalition of his enemies – Constantine, King of the Scots; Owain ap Dyfnwal, King of the Cumbrians; and Olaf Guthfrithson, King of Dublin – at the battle of Brunanburh, celebrated by a poem in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, opened the way for him to be hailed as the first king of England.[94] Æthelstan's legislation shows how the king drove his officials to do their respective duties. He was uncompromising in his insistence on respect for the law. However this legislation also reveals the persistent difficulties which confronted the king and his councillors in bringing a troublesome people under some form of control. His claim to be "king of the English" was by no means widely recognised.[95] The situation was complex: the Hiberno-Norse rulers of Dublin still coveted their interests in the Danish kingdom of York; terms had to be made with the Scots, who had the capacity not merely to interfere in Northumbrian affairs, but also to block a line of communication between Dublin and York; and the inhabitants of northern Northumbria were considered a law unto themselves. It was only after twenty years of crucial developments following Æthelstan's death in 939 that a unified kingdom of England began to assume its familiar shape. However, the major political problem for Edmund and Eadred, who succeeded Æthelstan, remained the difficulty of subjugating the north.[96] In 959 Edgar is said to have "succeeded to the kingdom both in Wessex and in Mercia and in Northumbria, and he was then 16 years old" (ASC, version 'B', 'C'), and is called "the Peacemaker".[96] By the early 970s, after a decade of Edgar's 'peace', it may have seemed that the kingdom of England was indeed made whole. In his formal address to the gathering at Winchester the king urged his bishops, abbots and abbesses "to be of one mind as regards monastic usage . . . lest differing ways of observing the customs of one Rule and one country should bring their holy conversation into disrepute".[97]

Athelstan's court had been an intellectual incubator. In that court were two young men named Dunstan and Æthelwold who were made priests, supposedly at the insistence of Athelstan, right at the end of his reign in 939.[98] Between 970 and 973 a council was held, under the aegis of Edgar, where a set of rules were devised that would be applicable throughout England. This put all the monks and nuns in England under one set of detailed customs for the first time. In 973, Edgar received a special second, 'imperial coronation' at Bath, and from this point England was ruled by Edgar under the strong influence of Dunstan, Athelwold, and Oswald, the Bishop of Worcester.

Along with the Britons and the settled Danes, some of the other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms disliked being ruled by Wessex. Consequently, the death of a Wessex king would be followed by rebellion, particularly in Northumbria.[89] Alfred's great-grandson, Edgar, who had come to the throne in 959, was crowned at Bath in 973 and soon afterwards the other British kings met him at Chester and acknowledged his authority.[99]

The presence of Danish and Norse settlers in the Danelaw had a lasting impact; the people there saw themselves as "armies" a hundred years after settlement:[100] King Edgar issued a law code in 962 that was to include the people of Northumbria, so he addressed it to Earl Olac "and all the army that live in that earldom".[100] There are over 3,000 words in modern English that have Scandinavian roots,[101][102] and more than 1,500 place-names in England are Scandinavian in origin; for example, topographic names such as Howe, Norfolk and Howe, North Yorkshire are derived from the Old Norse word haugr meaning hill, knoll, or mound.[102][103] The interaction of Scandinavians with the Anglo-Saxons, during this period, is known as the "Viking Age" or in academic circles the Anglo-Scandinavian period.[104]

England under the Danes and the Norman Conquest (978–1066)

Edgar died in 975, sixteen years after gaining the throne, while still only in his early thirties. Some magnates supported the succession of his younger son, Æthelred, but his elder half-brother, Edward was elected, aged about twelve. His reign was marked by disorder, and three years later, in 978, he was assassinated by some of his half-brother's retainers.[105] Æthelred succeeded, and although he reigned for thirty-eight years, one of the longest reigns in English history, he earned the name "Æthelred the Unready", as he proved to be one of England's most disastrous kings.[106] William of Malmesbury, writing in his Chronicle of the kings of England about one hundred years later, was scathing in his criticism of Æthelred, saying that he occupied the kingdom, rather than governed it.[107]

Just as Æthelred was being crowned, the Danish Harald Gormsson was trying to force Christianity onto his domain.[108] Many of his subjects did not like this idea, and shortly before 988, Sweyn, his son, drove his father from the kingdom.[108] The rebels, dispossessed at home, probably formed the first waves of raids on the English coast.[108] The rebels did so well in their raiding that the Danish kings decided to take over the campaign themselves.[109]

In 991 the Vikings sacked Ipswich, and their fleet made landfall near Maldon in Essex.[109] The Danes demanded that the English pay a ransom, but the English commander Byrhtnoth refused; he was killed in the ensuing Battle of Maldon, and the English were easily defeated.[109] From then on the Vikings seem to have raided anywhere at will; they were contemptuous of the lack of resistance from the English. Even the Alfredian systems of burhs failed.[110] Æthelred seems to have just hidden, out of range of the raiders.[110]

Payment of Danegeld

By the 980s the kings of Wessex had a powerful grip on the coinage of the realm. It is reckoned there were about 300 moneyers, and 60 mints, around the country.[111] Every five or six years the coinage in circulation would cease to be legal tender and new coins were issued.[111] The system controlling the currency around the country was extremely sophisticated; this enabled the king to raise large sums of money if needed.[112][113] The need indeed arose after the battle of Maldon, as Æthelred decided that, rather than fight, he would pay ransom to the Danes in a system known as Danegeld.[114] As part of the ransom, a peace treaty was drawn up that was intended to stop the raids. However, rather than buying the Vikings off, payment of Danegeld only encouraged them to come back for more.[115]

The Dukes of Normandy were quite happy to allow these Danish adventurers to use their ports for raids on the English coast. The result was that the courts of England and Normandy became increasingly hostile to each other.[108] Eventually, Æthelred sought a treaty with the Normans, and ended up marrying Emma, daughter of Richard I, Duke of Normandy in the Spring of 1002, which was seen as an attempt to break the link between the raiders and Normandy.[110][116]

Then, on St. Brice's day in November 1002, Danes living in England were slaughtered on the orders of Æthelred.[117]

Rise of Cnut

In mid-1013, Sven Forkbeard, King of Denmark, brought the Danish fleet to Sandwich, Kent.[118] From there he went north to the Danelaw, where the locals immediately agreed to support him.[118] He then struck south, forcing Æthelred into exile in Normandy (1013–1014). However, on 3 February 1014, Sven died suddenly.[118] Capitalising on his death, Æthelred returned to England and drove Sven's son, Cnut, back to Denmark, forcing him to abandon his allies in the process.[118]

In 1015, Cnut launched a new campaign against England.[118] Edmund fell out with his father, Æthelred, and struck out on his own.[119] Some English leaders decided to support Cnut, so Æthelred ultimately retreated to London.[119] Before engagement with the Danish army, Æthelred died and was replaced by Edmund.[119] The Danish army encircled and besieged London, but Edmund was able to escape and raised an army of loyalists.[119] Edmund's army routed the Danes, but the success was short-lived: at the Battle of Ashingdon, the Danes were victorious, and many of the English leaders were killed.[119] Cnut and Edmund agreed to split the kingdom in two, with Edmund ruling Wessex and Cnut the rest.[119][120]

In 1017, Edmund died in mysterious circumstances, probably murdered by Cnut or his supporters, and the English council (the witan) confirmed Cnut as king of all England.[119] Cnut divided England into earldoms: most of these were allocated to nobles of Danish descent, but he made an Englishman earl of Wessex. The man he appointed was Godwin, who eventually became part of the extended royal family when he married the king's sister-in-law.[121] In the summer of 1017, Cnut sent for Æthelred's widow, Emma, with the intention of marrying her.[122] It seems that Emma agreed to marry the king on condition that he would limit the English succession to the children born of their union.[123] Cnut already had a wife, known as Ælfgifu of Northampton, who bore him two sons, Svein and Harold Harefoot.[123] The church, however, seems to have regarded Ælfgifu as Cnut's concubine rather than his wife.[123] In addition to the two sons he had with Ælfgifu, he had a further son with Emma, who was named Harthacnut.[123][124]

When Cnut's brother, Harald II, King of Denmark, died in 1018, Cnut went to Denmark to secure that realm. Two years later, Cnut brought Norway under his control, and he gave Ælfgifu and their son Svein the job of governing it.[124]

Edward becomes king

One result of Cnut's marriage to Emma was to precipitate a succession crisis after his death in 1035,[124] as the throne was disputed between Ælfgifu's son, Harald Harefoot, and Emma's son, Harthacnut.[125] Emma supported her son by Cnut, Harthacnut, rather than a son by Æthelred.[126] Her son by Æthelred, Edward, made an unsuccessful raid on Southampton, and his brother Alfred was murdered on an expedition to England in 1036.[126] Emma fled to Bruges when Harald Harefoot became king of England, but when he died in 1040 Harthacnut was able to take over as king.[125] Harthacnut quickly developed a reputation for imposing high taxes on England.[125] He became so unpopular that Edward was invited to return from exile in Normandy to be recognised as Harthacnut's heir,[126][127] and when Harthacnut died suddenly in 1042 (probably murdered), Edward (known to posterity as Edward the Confessor) became king.[126]

Edward was supported by Earl Godwin of Wessex and married the earl's daughter. This arrangement was seen as expedient, however, as Godwin had been implicated in the murder of Alfred, the king's brother. In 1051 one of Edward's in-laws, Eustace, arrived to take up residence in Dover; the men of Dover objected and killed some of Eustace's men.[126] When Godwin refused to punish them, the king, who had been unhappy with the Godwins for some time, summoned them to trial. Stigand, the Archbishop of Canterbury, was chosen to deliver the news to Godwin and his family.[128] The Godwins fled rather than face trial.[128] Norman accounts suggest that at this time Edward offered the succession to his cousin, William (duke) of Normandy (also known as William the Conqueror, William the Bastard, or William I), though this is unlikely given that accession to the Anglo-Saxon kingship was by election, not heredity – a fact which Edward would surely have known, having been elected himself by the Witenagemot.

The Godwins, having previously fled, threatened to invade England. Edward is said to have wanted to fight, but at a Great Council meeting in Westminster, Earl Godwin laid down all his weapons and asked the king to allow him to purge himself of all crimes.[129] The king and Godwin were reconciled,[129] and the Godwins thus became the most powerful family in England after the king.[130][131] On Godwin's death in 1053, his son Harold succeeded to the earldom of Wessex; Harold's brothers Gyrth, Leofwine, and Tostig were given East Anglia, Mercia, and Northumbria.[130] The Northumbrians disliked Tostig for his harsh behaviour, and he was expelled to an exile in Flanders, in the process falling out with his brother Harold, who supported the king's line in backing the Northumbrians.[132][133]

Death of Edward the Confessor

On 26 December 1065, Edward was taken ill.[133] He took to his bed and fell into a coma; at one point he woke and turned to Harold Godwinson and asked him to protect the Queen and the kingdom.[134][135] On 5 January 1066 Edward the Confessor died, and Harold was declared king.[133] The following day, 6 January 1066, Edward was buried and Harold crowned.[135][136]

Although Harold Godwinson had "grabbed" the crown of England, others laid claim to it, primarily William, Duke of Normandy, who was cousin to Edward the Confessor through his aunt, Emma of Normandy.[137] It is believed that Edward had promised the crown to William.[126] Harold Godwinson had agreed to support William's claim after being imprisoned in Normandy, by Guy of Ponthieu. William had demanded and received Harold's release, then during his stay under William's protection it is claimed, by the Normans, that Harold swore "a solemn oath" of loyalty to William.[138]

Harald Hardrada ("The Ruthless") of Norway also had a claim on England, through Cnut and his successors.[137] He had a further claim based on a pact between Harthacnut, King of Denmark (Cnut's son) and Magnus, King of Norway.[137]

Tostig, Harold's estranged brother, was the first to move; according to the medieval historian Orderic Vitalis, he travelled to Normandy to enlist the help of William, Duke of Normandy, later to be known as William the Conqueror.[137][138][139] William was not ready to get involved so Tostig sailed from the Cotentin Peninsula, but because of storms ended up in Norway, where he successfully enlisted the help of Harald Hardrada.[139][140] The Anglo Saxon Chronicle has a different version of the story, having Tostig land in the Isle of Wight in May 1066, then ravaging the English coast, before arriving at Sandwich, Kent.[136][140] At Sandwich Tostig is said to have enlisted and press-ganged sailors before sailing north where, after battling some of the northern earls and also visiting Scotland, he eventually joined Hardrada (possibly in Scotland or at the mouth of the river Tyne).[136][140]

Battle of Fulford and aftermath

According to the Anglo Saxon Chronicle (Manuscripts D and E) Tostig became Hardrada's vassal and then with 300 or so longships sailed up the Humber Estuary bottling the English fleet in the river Swale and then landed at Riccall on the Ouse.[140][141] They marched towards York, where they were confronted, at Fulford Gate, by the English forces that were under the command of the northern earls, Edwin and Morcar; the Battle of Fulford followed, on 20 September, which was one of the bloodiest battles of medieval times.[142] The English forces were routed, though Edwin and Morcar escaped. The victors entered the city of York, exchanged hostages and were provisioned.[143] Hearing the news whilst in London, Harold Godwinson force-marched a second English army to Tadcaster by the night of the 24th, and after catching Harald Hardrada by surprise, on the morning of 25 September, Harold achieved a total victory over the Scandinavian horde after a two-day-long engagement at the Battle of Stamford Bridge.[144] Harold gave quarter to the survivors allowing them to leave in 20 ships.[144]

William of Normandy sails for England

Harold would have been celebrating his victory at Stamford Bridge on the night of 26/27 September 1066, while William of Normandy's invasion fleet set sail for England on the morning of 27 September 1066.[145] Harold marched his army back down to the south coast, where he met William's army, at a place now called Battle just outside Hastings.[146] Harold was killed when he fought and lost the Battle of Hastings on 14 October 1066.[147]

The Battle of Hastings virtually destroyed the Godwin dynasty. Harold and his brothers Gyrth and Leofwine were dead on the battlefield, as was their uncle Ælfwig, Abbot of Newminster. Tostig had been killed at Stamford Bridge. Wulfnoth was a hostage of William the Conqueror. The Godwin women who remained were either dead or childless.[148]

William marched on London. The city leaders surrendered the kingdom to him, and he was crowned at Westminster Abbey, Edward the Confessor's new church, on Christmas Day 1066.[149] It took William a further ten years to consolidate his kingdom, during which any opposition was suppressed ruthlessly; in a particularly brutal process known as the Harrying of the North, William issued orders to lay waste the north and burn all the cattle, crops and farming equipment and to poison the earth.[150] According to Orderic Vitalis, the Anglo-Norman chronicler, over 100,000 people died of starvation.[151] Figures based on the returns for the Domesday Book estimate that the population of England in 1086 was about 2.25 million, so 100,000 deaths, due to starvation, would have equated to 5 per cent of the population.[152]

By the time of William's death in 1087 it was estimated that only about 8 per cent of the land was under Anglo-Saxon control.[149] Nearly all the Anglo-Saxon cathedrals and abbeys of any note had been demolished and replaced with Norman-style architecture by 1200.[153]

See also

- Anglo-Saxon art

- Anglo-Saxon architecture

- Old English literature

- Anglo-Saxon monarchs

- Anglo-Saxon warfare

- Anglo-Saxons

- Coinage in Anglo-Saxon England

- Government in Anglo-Saxon England

- History of England

- History of the English penny (c. 600 – 1066)

- Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England

- Timeline of Anglo-Saxon England

Notes

- ^ Charles Thomas discusses the introduction of Christianity within the Roman Empire, from the Diocletianic Persecution to it eventually being tolerated and how it affected England. [16]

- ^ The author Michael Jones suggests the British were supporters of the Pelagian heresy, and that the numbers of Christians were higher than Gildas reports.[18]

- ^ Although Bede implies that the Jutes originated from Jutland, there is no consensus amongst historians of their origin[35]

- ^ Jones suggestes that "the repetitious entries for invading ships in the Chronicle (three ships of Hengest and Horsa; three ships of Aella; five ships of Cerdic and Cynric; two ships of Port; three ships of Stuf and Wihtgar), drawn from preliterate traditions including bogus eponyms and duplications, might be considered a poetic convention.[36]

- ^ From its reference to "Aldfrith, who now reigns peacefully" it must date to between 685 and 704.[50]

Citations

- ^ Schama, Simon (2003). A History of Britain 1: 3000 BC-AD 1603 At the Edge of the World? (Paperback 2003 ed.). London: BBC Worldwide. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-563-48714-2.

- ^ Higham & Ryan 2013, pp. 7–19.

- ^ See Carlson, David (2017). "Procopius's Old English". Byzantinische Zeitschrift=. 110 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1515/bz-2017-0003. citing Procopius, Wars, book VIII, xx. Elsewhere Procopius mentions the Warini living immediately south of the Danes, Book VI, xv.

- ^ a b Nicholas Brooks (2003). "English Identity from Bede to the Millenium". The Haskins Society Journal. 14: 35–50.

- ^ Campbell. The Anglo-Saxon State. p. 10

- ^ Ward-Perkins, Bryan (2000). "Why did the Anglo-Saxons not become more British?". The English Historical Review. 115 (462): 513–533. doi:10.1093/ehr/115.462.513.

- ^ Hills, C. (2003) Origins of the English Duckworth, London. ISBN 0-7156-3191-8, p. 67

- ^ Halsall 2013, pp. 97, 230.

- ^ Springer, Matthias (2004), Die Sachsen, pp. 32–42

- ^ Springer, Matthias (2004), Die Sachsen, pp. 33–35

- ^ Drinkwater, John F. (2023), "The 'Saxon Shore' Reconsidered", Britannia, 54: 275–303, doi:10.1017/S0068113X23000193

- ^ Springer, Matthias (2004), Die Sachsen, p. 36

- ^ Higham & Ryan 2013, p. 41.

- ^ Stacey 2003, p. 234.

- ^ Snyder.The Britons. pp. 106–07

- ^ Thomas 1981, pp. 47–50.

- ^ R. M. Errington Roman Imperial Policy from Julian to Theodosius. Chapter VIII. Theodosius

- ^ Jones 1998, pp. 174–85.

- ^ Snyder,The Britons, p. 105.In 5th and 6th centuries Britons in large numbers adopted Christianity..

- ^ a b Snyder, The Britons, pp. 116–25

- ^ Charles-Edwards. After Rome:Society, Community and Identity. p. 97

- ^ a b Charles-Edwards. After Rome:Conversion to Christianity. p. 132

- ^ Halsall 2013, p. 13.

- ^ Dewing, H B (1962). Procopius: History of the Wars Books VII and VIII with an English Translation (PDF). Harvard University Press. pp. 252–255. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ Gildas (1899), The Ruin of Britain, David Nutt, pp. 60–61

- ^ Higham, Nicholas (1995). An English Empire: Bede and the Early Anglo-Saxon Kings. Manchester University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-7190-4424-3.

- ^ Patrick Sims-Williams, 'The Settlement of England in Bede and the Chronicle', Anglo-Saxon England, 12 (1983), 1–41.

- ^ Bede's Ecclesiastical History, Bk I, Ch 15 and Bk II, Ch 5.

- ^ Giles 1843b:188–189, Bede's Ecclesiastical History, Bk V, Ch 9.

- ^ Halsall 2013, p. 293.

- ^ Halsall 2013, p. 61.

- ^ Gretzinger, J; Sayer, D; Justeau, P (2022), "The Anglo-Saxon migration and the formation of the early English gene pool", Nature, 610 (7930): 112–119, Bibcode:2022Natur.610..112G, doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05247-2, PMC 9534755, PMID 36131019

- ^ Norman F. Cantor, The Civilization of the Middle Ages1993:163f.

- ^ Giles 1843a:72–73, Bede's Ecclesiastical History, Bk I, Ch 15.

- ^ Martin 1971, pp. 83–104.

- ^ Jones 1998, p. 71.

- ^ Morris, The Age of Arthur, Chapter 16: English Conquest

- ^ Snyder.The Britons. p. 85

- ^ Stenton. Anglo-Saxon England. p. 29.

- ^ Stenton. Anglo-Saxon England. p. 30.

- ^ Morris. The Age of Arthur. p. 299

- ^ Bede Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Tr. Shirley-Price, I.25

- ^ Charles-Edwards, After Rome:Conversion to Christianity, p. 127

- ^ Charles-Edwards, After Rome:Conversion to Christianity, pp. 124–39

- ^ Charles-Edwards After-Rome: Nations and Kingdoms, pp. 38–39

- ^ Snyder,The Britons, p. 176.

- ^ Bede, History of the English, II.20

- ^ Snyder, The Britons, p. 177

- ^ Bede, Book III, chapters 3 and 5.

- ^ Stenton 1971, p. 88.

- ^ Campbell 1982, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Jennifer O'Reilly, After Rome: The Art of Authority, pp. 144–48

- ^ a b c Bede. History of the English People, III.25 and III.26

- ^ Barefoot. The English Road to Rome. p. 30

- ^ a b c d Snyder.The Britons. p. 178

- ^ Snyder.The Britons. p. 212

- ^ a b Snyder.The Britons.pp. 178–79

- ^ Yorke, B A E 1985: 'The kingdom of the East Saxons.' Anglo-Saxon England 14, 1–36

- ^ Stenton. Anglo-Saxon England. p. 231

- ^ Dumville, David N., Simon Keynes, and Susan Irvine, eds. The Anglo-Saxon chronicle: a collaborative edition. MS E. Vol. 7. Ds Brewer, 2004.

- ^ Swanton, Michael (1996). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-92129-9.

- ^ Whitelock, Dorothy, ed. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1965.

- ^ Bede, Saint. The Ecclesiastical History of the English People: The Greater Chronicle; Bede's Letter to Egbert. Oxford University Press, 1994.

- ^ Keynes, Simon. "Mercia and Wessex in the ninth century." Mercia. An Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe, ed. Michelle P. Brown/Carol Ann Farr (London 2001) (2001): 310–328.

- ^ a b c d e Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England, p. 123

- ^ Sawyer, Peter Hayes, ed. Illustrated history of the Vikings. Oxford University Press, 2001

- ^ Sawyer, The Oxford illustrated history of Vikings, p. 1.

- ^ a b Sawyer, The Oxford illustrated history of Vikings, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Standard English words which have a Scandinavian Etymology. Viking: "Northern pirate. Literally means creek dweller."

- ^ Starkey,Monarchy, Chapter 6: Vikings

- ^ Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 793.This year came dreadful fore-warnings over the land of the Northumbrians, terrifying the people most woefully: these were immense sheets of light rushing through the air, and whirlwinds, and fiery dragons flying across the firmament. These tremendous tokens were soon followed by a great famine: and not long after, on the sixth day before the ides of January in the same year, the harrowing inroads of heathen men made lamentable havoc in the church of God in Holy-island (Lindisfarne), by rapine and slaughter.

- ^ a b c d Starkey, Monarchy, p. 51

- ^ Starkey, Monarchy p. 65

- ^ a b c d Asser, Alfred the Great, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Asser, Alfred the Great, p. 22.

- ^ Medieval Sourcebook: Alfred and Guthrum's Peace

- ^ Wood, The Domesday Quest, Chapter 9: Domesday Roots. The Viking Impact

- ^ a b Starkey, Monarchy, p. 63

- ^ Horspool, Alfred, p. 102. A hide was somewhat like a tax – it was the number of men required to maintain and defend an area for the King. The Burghal Hideage defined the measurement as one hide being equivalent to one man. The hidage explains that for the maintenance and defence of an acre's breadth of wall, sixteen hides are required.

- ^ Anglo-Saxon Chronicle 894.

- ^ Starkey, Monarchy, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Starkey, Monarchy, p. 64

- ^ Anglo-Saxon Chronicle 891

- ^ Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 891–896

- ^ a b Horspool, "Why Alfred Burnt the Cakes", The Last War, pp. 104–10.

- ^ a b Horspool, "Why Alfred Burnt the Cakes", pp. 10–12

- ^ Asser, Alfred the Great, III pp. 121–60. Examples of King Alfred's writings

- ^ Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 899

- ^ a b c Starkey, Monarchy, p. 71

- ^ Welch, Late Anglo-Saxon England pp. 128–29

- ^ a b Keynes, Simon. "Edward, King of the Anglo-Saxons."." Edward the Elder: 899 924 (2001): 40–66.

- ^ Dumville, David N. Wessex and England from Alfred to Edgar: six essays on political, cultural, and ecclesiastical revival. Boydell Press, 1992.

- ^ Keynes, Simon. King Athelstan's books. University Press, 1985.

- ^ Hare, Kent G. "Athelstan of England: Christian king and hero." The Heroic Age 7 (2004).

- ^ Keynes, Simon. "Edgar, King of the English 959–975 New Interpretations." (2008).

- ^ a b Dumville, David N. "Between Alfred the Great and Edgar the Peacemaker: Æthelstan, First King of England." Wessex and England from Alfred to Edgar (1992): 141–171.

- ^ Regularis concordia Anglicae nationis, ed. T. Symons (CCM 7/3), Siegburg (1984), p.2 (revised edition of Regularis concordia Anglicae nationis monachorum sanctimonialiumque: The Monastic Agreement of the Monks and Nuns of the English Nation, ed. with English trans. T. Symons, London (1953))

- ^ Gretsch, Mechthild. "Myth, Rulership, Church and Charters: Essays in Honour of Nicholas Brooks." The English Historical Review 124.510 (2009): 1136–1138.

- ^ Keynes, 'Edgar', pp. 48–51

- ^ a b Woods, The Domesday Quest, pp. 107–08

- ^ The Viking Network: Standard English words which have a Scandinavian Etymology.

- ^ a b Crystal, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language pp. 25–26.

- ^ Ordnance Survey: Guide to Scandinavian origins of place names in Britain

- ^ Karkov 2012, p. 153.

- ^ Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, pp. 372–373

- ^ Starkey, Monarchy, p. 76. The modern ascription 'Unready' derives from the Anglo-Saxon word unraed, meaning "badly advised or counseled".

- ^ Malmesbury, Chronicle of the kings of England, pp. 165–66. In the year of our Lord's incarnation 979, Ethelred ... obtaining the kingdom, occupied rather than governed it, for thirty-seven years. The career of his life is said to have been cruel in the beginning, wretched in the middle and disgraceful in the end.

- ^ a b c d Stenton. Anglo Saxon England. p. 375

- ^ a b c Starkey, Monarchy, p. 79

- ^ a b c Starkey, Monarchy, p. 80

- ^ a b Wood, Domesday Quest, p. 124

- ^ Campbell, The Anglo Saxon State, p. 160. "..it has to be accepted that early eleventh century kings could raise larger sums in taxation than could most of their medieval successors. The numismatic evidence for the scale of the economy is extremely powerful, partly because it demonstrates how very many coins were struck, and also because it provides strong indications for extensive foreign trade."

- ^ Wood, Domesday Quest, p. 125

- ^ Stenton. Anglo-Saxon England. p. 376

- ^ Stenton. Anglo-Saxon England. p. 377. The treaty was arranged.. by Archbishop Sigeric of Canterbury and Ælfric and Æthelweard, the ealdermen of the two West Saxon provinces.

- ^ Williams, Aethelred the Unready, p. 54

- ^ Williams, Æthelred the Unready, pp. 52–53.

- ^ a b c d e Sawyer. Illustrated History of Vikings. p. 76

- ^ a b c d e f g Wood, In Search of the Dark Ages, pp. 216–22

- ^ Anglo Saxon Chronicle, 1016

- ^ Starkey, Monarchy, p. 94.

- ^ Anglo Saxon Chronicle, 1017: ..before the calends of August the king gave an order to fetch him the widow of the other king, Ethelred, the daughter of Richard, to wife.

- ^ a b c d Brown. Chibnal. Proceedings of the Battle Conference on Anglo-Norman studies. pp. 160–61

- ^ a b c Lapidge, Anglo-Saxon England, pp. 108–09

- ^ a b c Lapidge. Anglo-Saxon England. pp. 229–30

- ^ a b c d e f Lapidge, Anglo-Saxon England, pp. 161–62

- ^ Lapidge, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 230

- ^ a b Barlow, 2002, pp. 57–58

- ^ a b Barlow, 2002, pp. 64–65

- ^ a b Woods, Dark Ages, pp. 229–30

- ^ Barlow, 2002, pp. 83–85. The value of the Godwins holdings can be discerned from the Domesday Book.

- ^ Barlow, 2002, pp. 116–23

- ^ a b c Anglo Saxon Chronicle, 1065 AD

- ^ Starkey, Monarchy p. 119

- ^ a b Starkey, Monarchy, p. 120

- ^ a b c Anglo Saxon Chronicle. MS C. 1066.

- ^ a b c d Woods, Dark Ages, pp. 233–38

- ^ a b Barlow, 2002, "Chapter 5: The Lull Before the Storm".

- ^ a b Vitalis. The Ecclesiastical history of England and Normandy. Volume i. Bk. III Ch. 11. pp. 461–64 65

- ^ a b c d Barlow, 2002, pp. 134–35.

- ^ Anglo Saxon Chronicle. MS D. 1066.

- ^ Barlow, 2002, p. 138

- ^ Barlow, 2002, pp. 136–137

- ^ a b Barlow, 2002, pp. 137–38

- ^ Woods, Dark Ages, pp. 238–40

- ^ Barlow, 2002, "Chapter 7: The Collapse of the Dynasty".

- ^ Woods, Dark Ages, p. 240.

- ^ Barlow, 2002, p. 156.

- ^ a b Woods, Dark Ages, pp. 248–49

- ^ Starkey. Monarchy. pp. 138–39

- ^ Vitalis. The ecclesiastical history. p. 28 His camps were scattered over a surface of one hundred miles numbers of the insurgents fell beneath his vengeful sword he levelled their places of shelter to the ground wasted their lands and burnt their dwellings with all they contained. Never did William commit so much cruelty, to his lasting disgrace, he yielded to his worst impulse and set no bounds to his fury condemning the innocent and the guilty to a common fate. In the fulness of his wrath he ordered the corn and cattle with the implements of husbandry and every sort of provisions to be collected in heaps and set on fire till the whole was consumed and thus destroyed at once all that could serve for the support of life in the whole country lying beyond the Humber There followed consequently so great a scarcity in England in the ensuing years and severe famine involved the innocent and unarmed population in so much misery that in a Christian nation more than a hundred thousand souls of both sexes and all ages perished..

- ^ Bartlett. England under the Normans. pp. 290–92

- ^ Wood. The Doomsday Quest. p. 141

References

- "Alfred and Guthrum's Peace". Internet Medieval Source Book. History Department of Fordham University. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- Allen, Brown R.; Chibnall, Marjorie, eds. (1979). Anglo-Norman Studies. Vol. I: Proceedings of the Battle Conference 1978. London: Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-107-8.

- "The Anglo Saxon Dooms, 560–975AD". Internet Medieval Source Book. History Department of Fordham University. Archived from the original on 11 January 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- Asser (1983). Alfred the Great. Translated by Lapidge, Keyne. Penguin Classic (published 2004). ISBN 978-0-14-044409-4.

- Attenborough, F.L. Tr., ed. (1922). The laws of the earliest English kings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780404565459. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- Barefoot, Brian (1993). The English Road to Rome. Upton-upon-Severn: Images. ISBN 1-897817-08-8.

- Barlow, Frank (2002). The Godwins. London: Pearson Longman. ISBN 0-582-78440-9.

- Bede (1903).

Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Translated by Jane, L.C. (Temple Classics ed.). London: J. M. Dent & Company.; the translation of the

Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Translated by Jane, L.C. (Temple Classics ed.). London: J. M. Dent & Company.; the translation of the  Continuation., based on a translation by A. M. Sellar (1907).

Continuation., based on a translation by A. M. Sellar (1907). - Bartlett, Robert (2000). J.M. Roberts (ed.). England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings 1075–1225. London: OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-925101-8.

- Bell, Andrew (2000). Andrew Bell-Fialkoff (ed.). The Role of Migration in the History of the Eurasian Steppe:Sedentary Civilization vs. 'Barbarian' and Nomad . New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-21207-0.

- Blair, John (2006). The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-921117-3.

- Brandon, Peter, ed. (1978). The South Saxons. Chichester: Phillimore. ISBN 0-85033-240-0.

- Campbell, J (1982). Campbell, James (ed.). The Anglo-Saxons. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-140-14395-9.

- Campbell, James (2000). The Anglo-Saxon State . Hambledon: Hambledon Continuum. ISBN 1-85285-176-7.

- Dio, Cassius Cocceianus (1924). E. Cary (ed.). Roman History: Bk. 56–60, v. 7 (2000 ed.). Harvard: LOEB. ISBN 0-674-99193-1.

- Charles-Edwards, Thomas (1981). Christianity in Roman Britain to AD 500. Berkeley: UC Berkeley. ISBN 0-520-04392-8.

- Charles-Edwards, Thomas (2003). Thomas Charles-Edwards (ed.). Short Oxford History of the British Isles: After Rome: Conversion to Christianity. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-924982-4.

- Charles-Edwards, Thomas (2003). Thomas Charles-Edwards (ed.). Short Oxford History of the British Isles: After Rome: Nations and Kingdoms. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-924982-4.

- Clark, David, and Nicholas Perkins, eds. Anglo-Saxon Culture and the Modern Imagination (2010)

- Crystal, David (2001). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. CUP. ISBN 0-521-59655-6.

- Dark, Ken (2000). Britain and the End of the Roman Empire. Stroud: NPI Media Group. ISBN 0-7524-1451-8.

- Esmonde Cleary, A. S. (1991). The ending of Roman Britain. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-23898-6.

- Gelling, Margaret; Anne, Coles (2000). The Landscape of Place-Names. Stamford: Tyas. ISBN 1-900289-26-1.

- Gildas (1848).

The Ruin of Britain. Translated by Habington; Giles, J.A.

The Ruin of Britain. Translated by Habington; Giles, J.A. - Giles, J.A. (1914). . London: G. Bell and Sons Ltd. – via Wikisource.

- Giles, John Allen, ed. (1843a), "Ecclesiastical History, Books I, II and III", The Miscellaneous Works of Venerable Bede, vol. II, London: Whittaker and Co. (published 1843)

- Giles, John Allen, ed. (1843b), "Ecclesiastical History, Books IV and V", The Miscellaneous Works of Venerable Bede, vol. III, London: Whittaker and Co. (published 1843)

- Halsall, Guy (2013). Worlds of Arthur: Facts & Fictions of the Dark Ages. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-870084-5.

- Henry of Huntingdon (1996). Diana E. Greenway (ed.). Historia Anglorum: the history of the English. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 0-19-822224-6.

- Higham, Nicholas J.; Ryan, Martin J. (2013). The Anglo-Saxon World. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12534-4.

- Higham, N. J. (1994). English Conquest: Gildas and Britain in the fifth century. Manchester: Manchester United Press. ISBN 0-7190-4080-9.

- Hines J., ed. (2003). The Ango-Saxons from the Migration Period to the Eighth Century: An Ethnographic Perspective. London: Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-034-5.

- Horspool, David (2006). Why Alfred Burned the Cakes. London: Profile Books. ISBN 978-1-86197-786-1.

- Hunter Blair, Peter (1963). Roman Britain and Early England 55 BC – AD 871. London: W W Norton. ISBN 0-393-00361-2.

- Ernest Rhys, ed. (1912). Anglo Saxon Chronicle. Translated by Ingram, Rev. James. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd.

- Jones, Martin, ed. (2004). Traces of ancestry: studies in honour of Colin Renfrew. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-902937-25-0.

- Jones, Michael E. (1998). The End of Roman Britain. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8530-5.

- Karkov, Catherine E (2012). "Postcolonial". In Jacqueline Stodnick; Renée R. Trilling (eds.). A Handbook of Anglo-Saxon Studies. Chichester: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4443-3019-9.

- Kelly S. E.; et al., eds. (1973–2007). Anglo-Saxon Charters Volumes: I–XIII. Oxford: OUP for the British Academy.

- Keynes, Simon (2008). "Edgar rex admirabilis". In Scragg, Donald (ed.). Edgar King of the English: New Interpretations. The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-399-4.

- Koch, John T. (2005). Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-85109-440-7.

- Lapidge, Michael Ed.; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (2001). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. London: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

- Mayr-Harting, Henry (1992). The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England. Pennsylvania: University Press Pennsylvania. ISBN 0-271-00769-9.

- Malcolm Errington, R. (2006). Roman Imperial Policy from Julian to Theodosius. Durham, NC: University of North Carolina. ISBN 0-8078-3038-0.

- Martin, Kevin M. (1971). "Some Textual Evidence Concerning the Continental Origins of the Invaders of Britain in the Fifth Century". Latomus. 30 (1): 83–104. JSTOR 41527856.

- Morris, John (1973). The Age of Arthur. London: Phoenix. ISBN 1-84212-477-3.

- Myers, J.N.L. (1989). The English Settlements. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-282235-7.

- Nennius (1848).

History of the Britons. Translated by Gunn, Rev. W.; Giles, J.A.

History of the Britons. Translated by Gunn, Rev. W.; Giles, J.A. - O'Reilly, Jennifer (2003). Thomas Charles-Edwards (ed.). Short Oxford History of the British Isles: After Rome: The Art of Authority. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-924982-4.

- Ordericus Vitalis (1853). Thomas Forester Tr. (ed.). The Ecclesiastical history of England and Normandy. Volume i. London: Henry G. Bohn.

- Ordericus Vitalis (1854). Thomas Forester Tr. (ed.). The Ecclesiastical history of England and Normandy. Volume ii. London: Henry G. Bohn.

- Pattison, John E. (2008). "Is it necessary to assume an apartheid-like social structure in Early Anglo-Saxon England?". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 275 (1650). Royal Society: 2423–2429. doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.0352. PMC 2603190. PMID 18430641.

- "Guide to Scandinavian origins of place names in Britain" (PDF). Ordnance Survey. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- Sawyer, Peter (2001). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings (3rd ed.). Oxford: OUP. ISBN 0-19-285434-8.

- Farmer, D.H., ed. (1990). Bede:Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Translated by Sherley-Price, Leo. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044565-X.

- Stacey, Robin Chapman (2003). Charles-Edwards, Thomas (ed.). After Rome. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-924982-4.

- Snyder, Christopher A. (2003). The Britons. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-22260-6.

- Starkey, David (2004). The Monarchy of England Volume I. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0-7011-7678-4.

- Stenton, F. M. (1971). Anglo-Saxon England 3rd edition. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-280139-5.

- "Standard English words which have a Scandinavian Etymology". The Viking Network. Archived from the original on 11 February 2010. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- Thomas, Charles (1981). Christianity in Roman Britain to AD 500. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04392-8.

- Ward-Perkins, Bryan (2005). The fall of Rome: and the end of civilization. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 0-19-280564-9.

- Webb J. F.; Farmer D. H., eds. (1983). The Age of Bede. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044437-8.

- Welch, Martin (1992). Anglo-Saxon England. London: English Heritage. ISBN 0-7134-6566-2.

- William of Malmesbury (1847). Chronicle of the kings of England:From the earliest period to the reign of King Stephen. Translated by Giles, J.A. London: Henry Bohn.

- Williams, Ann (2003). Aethelred the Unready: The Ill-Counselled King. Hambledon: Hambledon Continuum. ISBN 1-85285-382-4.

- Wood, Michael (1985). The Domesday Quest. London: BBC. ISBN 0-15-352274-7.

- Wood, Michael (2005). In Search of the Dark Ages. London: BBC. ISBN 978-0-563-52276-8.

- Yorke, Barbara (1990). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. London: Taylor & Francis Ltd. ISBN 978-0-415-16639-3.

Further reading

- Curry, Andrew (21 September 2022). "Migration, not conquest, drove Anglo-Saxon takeover of England". Science.

You must be logged in to post a comment.