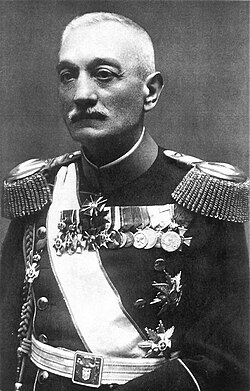

Prince Arsen of Yugoslavia

| Prince Arsenije | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Prince Arsenije Arsen of Yugoslavia in his later years, dressed in his full military uniform. (1920s) | |||||

| Born | 16 April 1859 Temesvár, Kingdom of Hungary, Austrian Empire | ||||

| Died | 19 October 1938 (aged 79) Paris, French Third Republic | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | Prince Paul of Yugoslavia | ||||

| |||||

| House | Karađorđević | ||||

| Father | Alexander Karađorđević, Prince of Serbia | ||||

| Mother | Persida Nenadović | ||||

| Military career | |||||

| Allegiance | Russian Empire Kingdom of Serbia Kingdom of Yugoslavia | ||||

| Rank | Major general (IRA) General (RSA) Army General (RYA) | ||||

| Unit | Cavalry | ||||

| Conflicts | Sino-French War Russo-Japanese War First Balkan War Second Balkan War World War I | ||||

Prince Arsenije "Arsen" of Yugoslavia (Serbian: Арсеније Карађорђевић / Arsenije Karađorđević; 16/17 April 1859 – 19 October 1938) was a dynast of the House of Karađorđević and an ancestor of the current cadet branch of the Serbian royal family. He long served as an officer in the Russian Imperial Army.

Biography

Early life and ancestry

He was born in Timișoara, then part of the Austrian Empire, a year after his father Prince Alexander Karađorđević had been deposed from the Serbian throne (the predecessor regime to the Yugoslavian monarchy). His mother was Persida Nenadović, a guiding force behind the throne and a member of the powerful Serbian Nenadović family. He was the youngest of ten children—six brothers and four sisters—only six of whom reached adulthood. His eldest brother was Peter I, King of Serbia and, later, King of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

Born and raised during his family's exile, he, unlike his brothers and sisters, had virtually no connection to Serbia, aside from his name and the stories of his ancestry. When he was nine years old, his father was arrested, and much of the family's property and money began to disappear. The only thing that did not change was his parents' determination to educate their children, even if it meant spending their "last kreutzer." Thus, during the family's exile, Stevan V. Popović was brought in as the private tutor of the two youngest boys, Prince George and Prince Arsenije.

After his time with the tutor and teacher, Arsen completed his primary schooling in Timișoara, and continued his education in Paris, where he graduated from the renowned Lycée Louis-le-Grand. The military school was highly prestigious and popular, and among its graduates were the future King Milan I of Serbia, a member of the rival Obrenović dynasty; King Nicholas I of Montenegro; and his cousin Božidar Karađorđević, a member of the senior branch of the Karađorđević family, with whose line he was not on good terms due to disputes over claims to the throne.

French Foreign Legion career

"By nature restless and adventurous," after finishing school he sought new challenges—which, for someone of his background at the time, meant only one thing: a military, warrior's career. Thus, in 1883, he joined the 2nd Battalion of the French Foreign Legion, and already in the autumn of that same year, as a newly accepted legionnaire, he departed for Vietnam, as part of the expeditionary corps of Admiral Sir John Corbett, as part of the French expeditionary forces taking part in the Sino-French War.

By that time, news had already reached France about the "madly brave" young Serbian prince, who had been decorated several times for his courage, solidarity with the soldiers, and for saving the life of an officer. He held the rank of sergeant during his service there. After the armistice with the Chinese was signed in 1885, he returned to Europe, only to depart once more with the French Foreign Legion—this time to Algeria, for which he received a medal for his service in the African campaigns.[1]

During his military expeditions—when his father was already weak and frail—Prince Alexander had distributed each of his children's share of the inheritance during his lifetime. Consequently, the only child explicitly mentioned in his will was his son Arsen. However, he left him nothing due to his lifestyle. The will states:

my son Arsenije lives a dissolute life and governs recklessly; therefore, I leave all movable and immovable property to my universal heir, my son George, who is obligated to give Arsen 5,000 florins.

It appears, however, that Alexander's original intention was not to entirely exclude Arsen from the inheritance. The will was written in 1884, and Arsen's exclusion was added later as a supplement to the original document. As a result, Prince Arsen ended up without an inheritance and entered life under those circumstances.[2]

Service in the Russian Imperial Army

After returning from Algeria, Prince Arsen left the French Foreign Legion and, on 29 November 1887, entered the service of the Russian Imperial Army. In Saint Petersburg, holding the rank of cornet (cavalry second lieutenant), he completed his training at the Second Konstantinovsky Military Academy. In 1888, owing both to his military experience and to his social standing, he was assigned to the elite Chevalier Guard Regiment of Her Imperial Majesty Empress Maria Feodorovna.

He arrived in Russia during a very difficult period of his life. His father had died in 1885, and three and a half years later he lost his older brother Prince George Karađorđević (1856-1889), to whom he had been deeply attached. Of the brothers, only he and Peter remained, and Arsen was often Peter's guest during the years Peter lived in Paris. It was under these circumstances that the Russian phase of his life began.[3]

Although he had a disastrous marriage, Arsen advanced steadily in his service with the Russian Imperial Army. In 1892, he was promoted to lieutenant, and in 1898 he became a captain 2nd rank, advancing later that same year to captain 1st rank. He attained the rank of colonel in 1903. During this period, Russia was at peace, which allowed him to travel more frequently to his beloved Paris and visit his brother in Geneva. This was also a time when the two brothers grew closer; due to the significant age difference, Arsen had been much closer to George, who had died in 1889.[4]

Personal life

Life reported in March 1884 that "Prince Arsene Kara-Georgevitch, son of the ex-ruler of Servia, is going to marry an American beauty with a fabulous dot. This is quite en regle".[5] However, no such marriage was later reported.

In January 1885, newspapers reported that Arsen had fought a further duel with Count Barberin.[6]

Prince Arsen was married in Uspenski Cathedral on 1 May 1892 to Aurora Pavlovna Demidova, Princess of San Donato, born a member of the fabulously wealthy Demidov family, which belonged to both the Russian and Italian nobility. She was the eldest daughter of Pavel Pavlovich Demidov, 2nd Prince of San Donato (whose uncle, Prince Anatoly Demidov, had been married to Napoleon's niece Princess Mathilde Bonaparte) by his second wife, Princess Elena Trubetskaya.[7]

It was an incident at a ball that led to an encounter, which would eventually result in his marriage to one of the most beautiful and sought-after women of the time. During the event, both Arsen and his friend Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim simultaneously chose Aurora as their partner for a mazurka, sparking a heated quarrel between the two friends.[8] She was fourteen years younger than Arsen, and their union came as a genuine surprise to the high society of Saint Petersburg. The details of how the couple decided to marry remain unknown, but contemporary gossip suggested that Arsen's motives were not purely romantic; some claimed he also sought her dowry to help settle debts incurred due to his gambling and extravagant lifestyle.

According to those who knew him, Arsen was entirely unsuited to the role of husband, while Aurora was certainly ill-prepared for motherhood. They were a deeply unhappy couple, which contributed to the brevity of their marriage. While still young, Arsen developed a tendency toward frivolous relationships and a craving for military adventure, and as an Army officer he spent much of his time away from home not only on military manoeuvres but also at the gaming tables of Paris.

Their only son was Prince Paul of Yugoslavia who was Regent of Yugoslavia from 9 October 1934 to 27 March 1941.[7] The couple first separated in 1894 and later divorced on 20 September 1897, due to Aurora's earlier liaison with the young Count Ernst Andreas von Manteuffel, which resulted in the birth of twin sons, Nikolai (1895–1933) and Sergei (1895–1912), whom Arsen refused to acknowledge as his own and as members of the House of Karadjordjevic. In Imperial Russia, divorce was administered by the Orthodox Church and subject to rigid ecclesiastical rules, making it both rare and procedurally complex. When Aurora Pavlovna sought a divorce from Prince Arsen Karađorđević, the proceedings extended over nearly two years and were not submitted to the Holy Synod until 15 January 1897. As part of the process, Arsen agreed to be designated the "guilty" party on the formal grounds of abandonment, a status that permanently barred him from remarrying but enabled Aurora, as the "innocent" party, to obtain legal freedom to do so. This arrangement was made on the condition that their son, Prince Paul, would not be raised in the same household as Aurora's "other" children, thereby allowing her the possibility to marry the father of her biological twin sons. The Holy Synod granted the divorce on 20 September 1897.[9][10]

Even before the divorce, one-year-old Paul was taken by his nanny to Nice, leaving Russia, which he would never return to. After the divorce, Aurora no longer harbored illusions about her own or Arsen's ability to raise the child, and her principal concern became determining who would assume responsibility for the infant Paul, whom neither parent was in a position to care for. Arsen, a professional soldier who spent long periods away from home, was further constrained by canon law, which barred him from remarrying and thus from providing Paul with a stepmother who might have assumed daily care. As a result, the question of Prince Paul's upbringing remained unresolved during the prolonged process of his parents' separation and divorce proceedings, which extended over several years.

Aurora initially asked her half-brother, Elim Pavlovich Demidov, 3rd Prince of San Donato, to adopt Paul, but as a career diplomat, he was unable to take on the responsibility and had to decline the offer. Aurora later wrote to her brother that she had lost "Arsene, the little one—everything, everything, everything," adding that her life felt irreparably broken and that all hope had been extinguished. She further remarked that signing the divorce papers "felt like signing my death certificate," a statement that underscores the profound emotional toll the proceedings had upon her.[10] Ultimately, in 1895, it was decided that, following the divorce proceedings, Paul's legal guardian would become his paternal uncle, Prince Peter Karađorđević, who was living in exile in Geneva at the time. Prince Paul later recalled that during his uncle Peter's lifetime, he spent more time with him than with his own children, who themselves were later educated in Russia.

From the time of his adoption, little Prince Paul saw his mother only twice more in his life.

The first occasion was when he was six years old: during a cruise on Lake Geneva, a lady on the deck suddenly took him into her arms and held him there, which seemed to him to last an eternity. She then introduced him to her friends as her son.

The second and final time was when he was eight. One winter evening, he was taken to a railway station and told to wait. When the train arrived, the same lady from the boat stepped out, embraced the confused child tightly, and then, tearfully, boarded the train that disappeared into the night—this being the last time Paul saw his mother.[3]

Aurora Pavlovna was remarried to Nicola, Count Palatine di Noghera in Genoa on 4 November 1897,[7] with whom she had three sons (the first born during her marriage to Arsen) and one surviving daughter. In 1896, she acquired the beautiful Villa Bria in Bussoleno, near Turin, where she lived with her second husband, spending her time between Florence, Cannes, the French Riviera, and Piedmont, marking the happiest period of her life. Tragically, Aurora Pavlovna passed away in Turin on 28 June 1904, succumbing to an infection caused by a rose thorn puncture. She was laid to rest in the Russian Orthodox Cemetery, Nice, France.[7][11]

Life in Serbia

In 1903, after Peter became the King of Serbia, he was summoned back to Serbia at the request of his brother. Until 1904, Arsen and his son Paul were subjects of the Russian Empire. Upon receiving Serbian citizenship on 26 April 1904, he was obliged to resign from regular service in the Imperial Russian Army.

There had been expectations that, as the king's brother, he would have prospects in the Serbian Royal Army and be assigned a position befitting his rank. However, this did not come to pass, largely due to the younger members of the Karađorđević family, who feared that their uncle, as an experienced soldier, might outshine them in the eyes of the public, and therefore did everything to prevent it.[12]

Disappointed by the course of events, and eager both for action and for earning a living, he decided to temporarily return St. Petersburg, and, at the end of the year, he volunteered to fight on Russia's side in the Russo-Japanese War in 1904. For his bravery in the Battle of Mukden, on 26 February 1905, the Russian Emperor Nicholas II awarded the Serbian Prince a gold sword set with diamonds and inscribed 'For Bravery.' This was a rare honor, reflecting the high esteem in which 'Colonel Karađorđević,' as he was known, was held at court, as only three other officers—Nikolai Yudenich, Paul von Rennenkampf, and Nikolai Ottovich von Essen—received such a jeweled sword crafted by the eminent jeweler Carl Blank.[13]

After the end of the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, the prince returned to Belgrade, where he had few official duties, leaving him with ample time for socializing. Since he knew relatively few people in the city, his companions were mostly court officials and army officers. He often spent his evenings at the tavern "Tri Šešira" in Skadarlija, where he felt "content that no one knew him," and enjoyed recounting his experiences from Asia and Russia. During the nighttime hours, if he hadn't gone out, he would often host card games in his apartment, accompanied by jokes, stories, anecdotes, and all kinds of bawdy tales.[14]

During his life in Serbia, the relationship between Arsen and his son was peculiar from the beginning and can be described as somewhat distant, owing to their starkly different characters—a difference quite noticeable from Prince Paul's earliest days. He was strikingly unlike the other members of the Karađorđević family, who were generally open, direct, and combative, with strong military inclinations—all qualities Paul notably lacked. This made his relationship with them unique and somewhat tense, as reflected in a 1906 letter from his father, Prince Arsen, to Paul's teacher, Milorad Pavlović-Krpa, whom Arsen had known since his youthful days in St. Petersburg, but with whom he became particularly close during his years in Belgrade. Namely, Paul had little or no interest in geography, the subject he was studying under Krpa, and consistently received the lowest possible marks. In the letter, Arsen wrote:

Please instruct my little Paul. He pretends to be naive. His eyes are sweet, and he always looks surprised, but he is only pretending. I know him well. He is most cunning and, worst of all, very jealous—a trait he did not inherit from me. There is little sincerity in him. Once you get to know him better, you will notice another unpleasant quality: he is deceitful. His uncle-in-law, Prince Semyon Abamelek-Lazarev, loves him greatly for that, as in this respect he resembles him very much.

Arsen's elder brother shared a similar assessment of Paul. As his official guardian, King Peter I, took note of the young prince's character too, summoning Krpa to an audience and advising him:

Continue to be strict with him, as is appropriate, for he believes he can get away with anything.[15]

King Peter issued a family statute for the members of the royal house, namely on 30 August 1909, after Arsen already left Serbia. Based on this royal statute, Prince Arsen and his descendants were entitled to the style of Highness. In the years that followed, namely in 1921, and later confirmed in 1931, Arsen and his line were upgraded to the style Royal Highness by his nephew, the new ruler, King Alexander I of Yugoslavia.[16]

One of his most famous love affairs from his Belgrade days was that with Gita Genčić (1873–1940), renowned for her oriental beauty, who had previously divorced her first husband, General Vojislav Cincar-Janković, because of her second husband, the politician Đorđe Genčić, Serbian Minister of National Economy, and later ended her marriage to Genčić following her affair with the Prince. To avoid a greater scandal, Arsen decided to leave Serbia in haste; and after that, he never technically returned to live there again.[17]

Return to Russia

After he left, he headed toward Paris, from where—determined to return to Russian service—he wrote, in French, a letter to Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, with whom he was on friendly terms. Until recently, the very existence of this letter was unknown, until the Russian ambassador to Serbia, Aleksander Konuzin, discovered it in the Russian State Archives and handed it over in 2011 to Arsenije's only granddaughter, Princess Elizabeth of Yugoslavia. In the letter he writes:

"Paris, 17/30 December 1908.

Madam,

I address Your Imperial Majesty as my sovereign and as the patroness of the former regiment in which I had the honor to serve, hoping that I will find in you benevolent protection.

After 42 years of exile, being near my brother's throne, I was, in repentance, forced to leave the service of the homeland that adopted me and that was so generously hospitable. Having patiently waited for the fulfillment of the promises that were made to me, today I am compelled to face the sad reality that not only has nothing been attempted on my behalf, but moreover, I now know that I can expect nothing ever again.

The right which I believed belonged to me—to take an appropriate position in the Serbian royal army, since I had the indescribable honor of serving in Russia—the property that had been confiscated from me unjustly, and all the other reasons which, as it seems to me, weigh against my name in a way impossible to refute and which I have in no way deserved, ought to be taken into consideration.

After six years, desiring a clear explanation, I allowed myself to write to my brother in order to assert my claims, asking him to bring an end to this dreadful situation. Reminding him of what I had done for him as a brother—sharing with him more than half of my wealth while he was living in Geneva—I asked him for any rank whatsoever in his army.

Since I had only a small pension—about 2,000 rubles a month—it was taken away from me. Now I have found myself without any income whatsoever. I allow myself to ask Your Imperial Majesty to intercede with His Majesty the Emperor so that he might graciously take me back into his service. Unfortunately, there is one great obstacle: I have several debts, and I have no means of paying them. Forgive me, Madam, for being compelled to lay such details before Your Majesty, but I must do so, regardless of the humiliation it may bring me. My pride prevents me from insisting.

I hope that my loyal friends will be willing to support my plea before Your Imperial Majesty and will present to you a situation perhaps unique in the world—far more shameful for those who created it than for the one who endures it—inflicted upon a prince who belonged to a ruling house such as my own. I will allow myself to hope that Your Majesty may judge it so, and I place my fate in your hands.

I pray to God that Your Majesty may rescue from terrible misfortune a faithful subject who lays at your feet assurances of his unwavering loyalty and respect.

Prince Arsen Karađorđević."[18]

After this letter and the Dowager Empress's intervention, he was accepted back into Russian service. However, during all the years of his absence, life in Saint Petersburg had changed — or more precisely, the people themselves had changed. Financially drained by the previous war, Russia no longer had as many balls with officers in full dress, nor lavish gatherings held for no particular reason.

He did not have a wide social circle, even though he had family living there — his niece Princess Helen, to whom he was particularly attached, as well as her aunts, the sisters of his late sister-in-law Zorka, Grand Duchesses Milica and Anastasia, who at that time were among the most prominent ladies in Saint Petersburg high society and in the Emperor's closest circle.

He remained on friendly terms with his comrades from the Chevalier Guard Regiment, mostly men of foreign origin, such as Mannerheim. He also liked playing cards and continued to gamble. In his past time, he enjoyed reading. He spoke German, French, Hungarian, English, Russian, and Serbian fluently, and he both read and wrote in all of them. The only thing that did not interest him at all was politics and ongoing political affairs.[19]

He remained in Russia until the outbreak of the First Balkan War, when he temporarily returned to Serbia via Paris, arriving in Niš with 30 foreign volunteers whom he had personally organized. On that occasion, he was given command of the cavalry. He remained in that position during the Second Balkan War with Bulgaria as well.

The entire Serbian press praised Prince Arsen, who during the Balkan Wars distinguished himself not only through "brilliant command" but also through personal courage on the battlefield. In the army they called him Arsa, as only his brother still addressed him. After the end of the Balkan Wars, he returned once again to Russia, where he remained until the outbreak of the World War I.[20]

Longing for the way of life he was accustomed to, he immediately placed himself at Serbia's disposal. However, in a letter dated 1 August 1914, Prime Minister Nikola Pašić informed him—through Miroslav Spalajković, the Serbian ambassador in Russia—that there was no place for him in the Serbian army. Disappointed, he had no choice but to once again offer his services to the Russian army during the war. He was transferred with them "to the border of East Prussia, to the command that had been assigned to him." Thus, on 6 December 1914, he became a Major General in the Imperial Russian Army and, as such, was sent to fight on the Eastern Front.

There, he came into conflict with Colonel Vladimir Nikolayevich Gatovsky, after Gatovsky, dissatisfied with the behavior of one officer, slapped the man across the face. It is not known exactly how Arsen reacted to the colonel's conduct, but it is known that as a result Gatovsky was demoted, while Arsen was transferred to the reserve staff of the Saint Petersburg Military District—effectively placing him outside any active military formation, which was precisely what Arsen desired to avoid. In practice, this marked the end of his military career. Gatovsky had his rank restored as early as 6 May 1916, and on 31 October 1917 he was promoted to Major General.[21]

The Russian revolution

At the end of 1917, during the turmoil of the Russian Revolution, Prince Arsen was arrested in the "Officers' Hunting Club", though the exact reason remains unknown. At the beginning of 1918 he was tried before a Revolutionary tribunal and was acquitted. It is not known whose intervention proved decisive on his behalf, since no influential person—not even his friends or relatives in high circles—dared to appear in court and testify for him. It was believed that the Bolsheviks, who were then taking control, did not wish to risk sentencing to death the brother of a foreign sovereign.[22]

Afterwards, he was forced to leave Russia forever in May 1918—the country in which he had lived for so many decades. His departure marked the end of the turbulent chapter of his life, the one recounted with varying degrees of truth in high society. Through the mediation of Serbian diplomacy, he first safely made his way to Sweden and then to France, where he settled permanently in Paris. He left behind his niece, Princess Helen, to whom he was deeply attached, who chose to remain in Russia so she could stay by the side of her husband, Prince John Konstantinovich of Russia, who was later taken and killed by the Bolsheviks.[23]

Life in Paris

He took up residence in an elegant and refined apartment at 2 Square Monceau, in the seventeenth arrondissement near Montmartre, where he died twenty years later. There he led a quiet, largely comfortable, almost retired life—with fewer friends, but very much on his own terms. He often spent time with the diplomat Miroslav Spalajković, who served as ambassador of the newly formed kingdom to France from 1922 to 1935. Arsen received a regular monthly royal appanage, along with additional income befitting a divisional, later promoted to army general, which included allowances for housing, heating, and household staff. In addition to these sources, he also received income from bank bonds purchased in his name through the royal court. He maintained savings accounts and bought shares in various banks, which provided him with further earnings, all overseen by the court's financial administration.

Arsen returned to Serbia only a few times: for the wedding of his nephew Alexander to Princess Maria of Romania in 1922—where he served as the second witness despite Alexander having been one of the reasons for his earlier departure from Serbia. At the time of his return to Serbia, Arsen, an exceptional soldier, posed a natural threat to overshadow his nephews George and Alexander, who, already embroiled in their own rivalry over the succession, could not risk his prominence. As a result, he was offered no significant position in the Royal Serbian Army, and, disappointed, he decided to return to serve in the Russian Empire.

He visited Serbia only a handful of times thereafter: for his son Paul's wedding in 1923, for the transfer of Karađorđe's relics to Oplenac in 1930, and for King Alexander I's funeral in 1934. His rare visits were partly due to the fact that he hardly knew anyone there anymore; he had no real circle of acquaintances, and contact with other relatives had largely faded. Though different in temperament, the one person who never abandoned him was his son Paul, a devoted son despite having seen his father only rarely in earlier years.

During his life in Paris, Arsen enjoyed gambling—mostly with former officers—and he often fell into debt, which the royal court later settled. He was not selfish; he frequently gave to charitable causes. In 1924, for example, he donated a sum of money to the volunteer community in Donji Kovilj on the occasion of the "day of consecration of the regimental flag."

Prince Arsen had a refined taste for elegant attire. Records from his Paris years note his purchases of a "cap of guaranteed fine cloth" and a "field cap of 420-grade serge," small examples of his fondness for quality and style. He was also an ardent admirer of Cuban cigars. In July 1928, he placed a substantial order through an American firm—a full crate weighing ninety-four kilograms and containing 2,750 cigars.

The shipment from Havana arrived by steamer in Trieste and was then forwarded to Belgrade. There, the unwieldy crate had to be divided into four large parcels, as its original weight exceeded the limits of the Paris postal service. The repacked cigars were finally dispatched to him by courier, sent on his behalf by Antoine Tony Szirmai (1871-1938), Hungarian-born, Paris-based sculptor and engraver, sho served as an official of the Serbian royal legation in Paris.

Since he was a passionate smoker, that quantity of cigars didn't last even a year. By January 12, 1929, the State Monopoly administration had issued an invoice to the Royal Court administration for 2,000 "Vardar" cigarettes, which were given to Prince Arsen. The invoice was stamped as "paid."

In addition, he did not lose interest in events in Serbia and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. He was subscribed to the newspaper Politika and the radical publication "Samouprava", although they often arrived irregularly because of an incorrect address. The letters were addressed using the abbreviation "Kara," taken from his surname, and were prepared by a courier in Belgrade, where it was assumed who the mail was for based on this nickname. This kind of carelessness infuriated him. He wrote to a man named Marko, who was responsible for the deliveries:

For God's sake, I have lived in the same house for six years, and you keep mixing up all the addresses. I only receive my letters after two months, and some I never receive at all, like the Politika I am subscribed to. If you put just ‘Kara' I will never receive it. This is not Belgrade, where everyone knows each other, but a city of 4,000,000 inhabitants.

During his years in France, he increasingly began to fall ill, suffering in particular from lung problems—a condition common among the Karađorđević family. Over time, he required people to look after him, and Tony Szirmai, a special attaché of the Ministry in Paris, eventually assumed the role of his personal secretary.

Old friends continued to visit him in Paris, including Mannerheim, with whom he would play cards, attend horse races, and place bets. He also continued to travel, and records mention his trips to England and Switzerland, as well as his visit to the French Riviera, where he stayed as a guest at Villa Traianon in Cap Ferrat, owned by his most beloved niece, Princess Helen of Russia. While staying with her, he took the opportunity to spend time with his son and daughter-in-law, who were also in Nice at the time. They met often, socialized, and usually had Sunday lunch together at Villa Otrada in Cannes.

Over the years, his relationship with his son became increasingly warm, thanks largely to Paul's efforts to care for him, even though Arsen did not think particularly highly of him, often remarking that in character Paul was "far more a Demidov than a Karađorđević." Arsen himself was considered unreliable, and according to his daughter-in-law Olga—who viewed him as "a drunkard and a gambler"—he was not held in high regard.

He was not much respected within the family, even though he himself both loved and esteemed Olga. It is recorded that one Easter he gave her a sum of money with which she was able to order a dress from Jean Patou, then one of the most exclusive fashion designers in Paris. It was Olga, who remained by his side, who recorded that toward the end of his life he had grown so weak that he could no longer sign his own checks and soon became increasingly frail, losing the will to eat, drink, or even speak, ultimately becoming utterly helpless. Until the end of his life, he continued sign his name everywhere as Arsenije, and never Arsen.[24]

Death and funeral

Prince Arsen died at 13:30h in Paris on 19 October 1938. In Yugoslavia, the court of King Peter II observed mourning from 19 October 1938 to 10 January 1939, the first six weeks being a period of deep mourning. Numerous European monarchs and heads of state sent telegrams of condolence, the most publicly noted of which was that of Adolf Hitler, addressed to his son, the Prince Regent. In Paris, where he lived in comfort in a lavish apartment, the main hall was converted into a chapel adorned with black draperies. After the death of His Royal Highness, officers of the Yugoslav Royal Army from the military mission in Paris maintained an honor guard by the bier for three days. After three days, his body was transported by train to the Slovenian town of Rakek, at the Yugoslav border. From there, it was conveyed by the royal train to Belgrade. On the journey from Ljubljana to Belgrade, the remains were accompanied by Prince Regent Paul and his wife, Princess Olga of Greece and Denmark, who had spent the last three weeks of her father-in-law's life at his bedside, during his final illness.

Prince Arsen was buried on 24 October 1938 in the royal mausoleum at Oplenac, with the highest state honors—honors worthy of a king. The solemn and dignified funeral was arranged at the wish of his son, revealing his deep attachment to his father despite the differences in their characters that had often led to disagreements between them. After his death, the 6th Cavalry Regiment of the Yugoslav Royal Army was named in his honor as the 'Prince Arsen Regiment'.[25]

Honours and awards

Honours

| Foreign Honours | |

| Order of Saint Vladimir, Fourth class,1905 | |

| Order of Saint Stanislaus, Second Class,1905 | |

| Gold Sword for Bravery, 1906 | |

| Order of Carol I | |

| Medal -"In memory of Russian -Japanese War " | |

| Order of St. George, Fourth Class, 1915 | |

| National Honours | |

| Order of Karađorđe's Star, First and Fourth Class | |

| Order of the Yugoslav Crown, First Class, 1930 | |

See also

References and notes

- ^ Siniša Ljepojević (2018). Knez Arsenije Karadjordjević (pages=29-31)

- ^ Siniša Ljepojević (2018). Knez Arsenije Karadjordjević (pages=27-28)

- ^ a b Siniša Ljepojević (2018). Knez Arsenije Karadjordjević (pp. 63–68)

- ^ Siniša Ljepojević (2018). Knez Arsenije Karadjordjević (pages=68-69)

- ^ "PARISIAN GOSSIP", Life, Thursday 27 March 1884, p. 18

- ^ "GOSSIP FROM PARIS", The World (London), Wednesday 07 January 1885, pp. 24–25

- ^ a b c d Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Fürstliche Häuser Vol. VIII. "Jugoslawien". C. A. Starke Verlag, 1968, pp. 95-36. (in German)

- ^ Siniša Ljepojević Knez Arsenije Karadjordjević (2018), p. 74

- ^ С. С. Щульц. Аврора. — СПб.: Из-во ДЕАН, 2004. — 208 с.; S.S. Schultz, Aurora, Saint Petersburg, ed. DEAN, 2004, 208 pages

- ^ a b "The Karageorgevitch Twins". Academia.edu. Retrieved 2026-01-18.

- ^ https://www.giornalelavoce.it/news/home/531267/la-famiglia-della-principessa-russa-demidoff-in-citta-mori-a-gassino-punta-da-una-rosa-velenosa.html

- ^ Siniša Ljepojević (2018). Knez Arsenije Karadjordjević (page=61)

- ^ Siniša Ljepojević (2018). Knez Arsenije Karadjordjević (page=80)

- ^ Siniša Ljepojević (2018). Knez Arsenije Karadjordjević (page=81)

- ^ Siniša Ljepojević (2018). Knez Arsenije Karadjordjević (page=82)

- ^ Siniša Ljepojević (2018). Knez Arsenije Karadjordjević (page=61)

- ^ Siniša Ljepojević (2018). Knez Arsenije Karadjordjević (pages=114-115)

- ^ Siniša Ljepojević (2018). Knez Arsenije Karadjordjević (pages=82-85)

- ^ Siniša Ljepojević (2018). Knez Arsenije Karadjordjević (pages=82-85)

- ^ Siniša Ljepojević (2018). Knez Arsenije Karadjordjević (pages=106-111)

- ^ Siniša Ljepojević (2018). Knez Arsenije Karadjordjević (pages=117-120)

- ^ Siniša Ljepojević (2018). Knez Arsenije Karadjordjević (page=120-121)

- ^ Siniša Ljepojević (2018). Knez Arsenije Karadjordjević (page=154)

- ^ Siniša Ljepojević (2018). Knez Arsenije Karadjordjević (pages=154-167)

- ^ Siniša Ljepojević (2018). Knez Arsenije Karadjordjević (pages=168-169)

External links

Media related to Prince Arsen of Yugoslavia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Prince Arsen of Yugoslavia at Wikimedia Commons