Religion in the Achaemenid Empire (Persian: دین در دوران هخامنشی ), continues to be a source of debate among academics. The available knowledge about the religious orientation of many of the early Achaemenid kings is incomplete, and the issue of Zoroastrianism of the Achaemenids has been a very controversial issue.[citation needed]

Elam religion

In the Persepolis fortification archive, Humban appears more commonly than any other Elamite or Persian deity, with a total of twenty six mentions (for comparison, Auramazdā, an early form of Ahura Mazda, appears only ten times).[1] It has been argued that in this period, he should be regarded as a Persian god, rather than a strictly Elamite one.[2] Overall he received the most offerings of all deities attested in textual sources.[3]The amount of grain offered to him by the Achaemenid administration was more than thrice as big as that offered to Auramazdā.[4] Offerings to him are designated as bakadaušiyam in multiple cases.[5] This term, while Elamite, is a loan from Old Persian, and can be translated as "(feast) of the offering to (a) god".[6] It accordingly likely designated a public feast.[7] Similar celebrations are attested only for a small number of other deities.[8] Wouter Henkelman suggests that the references to bakadaušiyam of Humban are therefore likely to reflect his popularity and status as a royal god.[9]most locations where Humban was worshiped in the Achemenid period were towns located close to the royal road network.[10]

Mary Boyce went as far as suggesting that the prominence of Humban in the Neo-Elamite period influenced the position of Ahura Mazda in later religious traditions of the Persians.[11]

Iranian religions

Mazdaism

It is often thought that the dominant religion of the Achaemenid Empire was Zoroastrianism, but scholars believe that this was not true. For example, 20th-century French linguist Émile Benveniste points out that Ahura Mazda is a very old god and the Zoroastrians used this name to designate the Zoroastrian god. Even the main role assigned to this god in Mazdasim is not a Zoroastrian innovation. The epithet Mazdasene (Mazda worshipper) found in Aramaic papyri from the Achaemenid era cannot be evidence that the Achaemenids were Zoroastrians, and the mention of the name Ahura Mazda in stone inscriptions is not evidence of this either. In the Achaemenid inscriptions, not only is Zoroastrianism not mentioned, but also nothing else is mentioned that could give these inscriptions a Zoroastrian color.[12]

Long before Zoroaster, the Iranians had specific religious beliefs and worshipped Ahura Mazda as a great god.[13] In the Behistun Inscription, Darius only mentions Ahura Mazda as "the greatest of the gods." Ahura Mazda's name appears 69 times in Behistun, and Darius claims to be under Ahura Mazda's protection 34 times. Darius did not claim that Ahura Mazda was the only existing god. Darius also did not mention Ahura Mazda's great rival Angremenu.[14]

Mithra

Mithra[15] was worshipped;[16][17] his temples and symbols were the most widespread,[18] most people bore names related to him[19] and most festivals were dedicated to him.[20][21]

Weshparkar

Weshparkar, was the Sogdian god of the Atmosphere and the Wind.[22] He corresponds to the Avestan god Vayu.[23] In Central Asia, Weshparkar has also been associated to the Indian god Shiva.[24]

Anahita

Since the reign of Artaxerxes II the name of the goddess Anahita is mentioned in inscriptions alongside Ahura Mazda and Mitra, and it is mentioned that the palace of Apadana was built at the request of Ahura Mazda, Nahed and Mitra. In this regard, Roman Ghershman writes that Anahita was worshipped by the Achaemenid Ardashir II and by his order, the figure of Anahita was worshipped in the temples of Shush, Iran, Takht-e Jamshid, Hegmatane, Babylon (Dawlatshahr), Damascus and Balkh.[25]

Oxus

The earliest textual evidence of the worship of Oxus, dated to the Achaemenid period, are personal names attested in Aramaic texts from Bactria from the fourth century BCE, such as Vaxšu-bandaka ("slave of Oxus" or "servant of Oxus"), Vaxšu-data ("created by Oxus")[26] and Vaxšu-abra-data ("given by the clouds of Oxus").[27] Further examples occur in Hellenistic sources, for example Oxybazos ("strong through Oxus"), Oxydates ("given by Oxus"), Mithroaxos ("[given by] Mithra and Oxus") and possibly Oxyartes (if the translation "protected by Oxus" is accepted).[28]

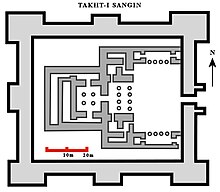

In Takht-i Sangin a temple dedicated to Oxus has been discovered.[29] According to a number of Muslim geographers from the ninth and tenth centuries, this area was customarily considered the beginning of Jayhun (Oxus), which might constitute a survival of an originally Bactrian tradition responsible for the selection of this location as a cult center of the related river god.[30] Excavations indicate that the temple was originally founded in the early Seleucid period, and remained in use until the reign of the Kushan king Huvishka.[31] One of the objects from this site is a stone altar following Greek artistic conventions inscribed with a dedication of a certain Atrosokes to Oxus.[26] His name is Bactrian and can be translated as "burning with sacred fire", and it is possible that he was a priest.[29] Further excavations revealed three more similar Greek inscriptions, seemingly left behind by Bactrian worshipers of Oxus.[32]

A seal with a human-headed bull from the Oxus Treasure is inscribed with Oxus' name written in the Aramaic script.[26] It has been pointed out that the objects found in the temple of Oxus in Takht-i Sangin have close parallels among these belonging to the Oxus Treasure, which might indicate the latter was originally found in the same location.[33] It has been suggested that priests of Oxus hid a number of objects out of fear of looting during a period of increased activity of the Yuezhi in the second half of the second century BCE, but failed to recover them, leaving the Oxus Treasure to only be discovered some two thousand years later.[34]

Other deities

The Persepolis tablets indicate that the royal palace was dedicated in the heart of Persia to the worship of various deities, some of which may have been identified as Iranian (Nariasanga, perhaps Zurvan) and others as Elamite deities still venerated in the same places where they had been for centuries before the arrival of the Persians (Humban, Napirisha).[35][36]

Ancient Mesopotamian religion

Anu

Xerxes' retaliation against the clergy of Uruk resulted in the collapse of Eanna as the center of Uruk's religious life and economy, and made the creation of a new system centered on the worship of Anu and his spouse of Antu, rather than Ishtar and Nanaya, possible.[37]

Antu

A change in Antu's status in Uruk occurred over the course of the Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, when she was elevated to the position of one of the lead deities of the city alongside Anu.[38] She came to be worshiped alongside him in a newly built temple, Bīt Rēš.[39] Its ceremonial name can be translated as "foremost temple".[40] Antu's cella in it was known as Egašananna, "house of the lady of heaven". One of its chambers was also designated as her bedroom, and was referred to with the ceremonial name Enir, possibly to be understood as Eanir (Akkadian bīt tānēḫi), "house of weariness".[41] According to Andrew R. George and Paul-Alain Beaulieu, Bīt Rēš might have developed from the É.SAG, a sanctuary of Lugalbanda attested in earlier periods whose name was written with the same signs, but this remains hypothetical.[42][43] Its establishment marked the first time in the history of Uruk when Eanna was not its main temple.[44] This development was a result of the rise of new priestly families in the aftermath of failed revolts which took place in 484 BCE and Xerxes I's retaliation against the participants.[45] The status of the city's former tutelary deity, Ishtar, declined, and some of her attributes were absorbed by Antu.[46] For example, in the text MLC 1890 Ninsianna, the personification of the planet Venus, who in earlier periods could be treated as a form of Ishtar, is instead treated as an epithet of Antu.[47] The kalû clergy of Uruk, responsible for Emesal prayers[48] and formerly associated with Ishtar, came to be linked to the cult of Anu and Antu instead in Seleucid times.[49] In some cases, the change makes it possible to date individual texts with no other direct indication of their age than their authors being a kalû in service of one of these deities.[50] It is not certain if Seleucid kings were involved in the worship of Antu and other deities of Uruk, though it has been argued that the attested building and renovation projects required royal support.[51]

Sumerian religion

Nanaya

After the reorganization of the pantheon of Uruk around Anu and Antu in the Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, Nanaya continued to be worshipped and she is attested as one of the deities whose statues were paraded in Uruk in a ritual procession accompanying Ishtar (rather than Antu) during a New Year celebration.[52] The scale of her popular cult in Uruk grew considerably through Seleucid times.[53]

Zoroastrianism in the Achaemenid Empire

Swedish Iranologist Henrik Samuel Nyberg believes that none of the essential characteristics of the Zoroastrian religion can be seen in the basic constructions of the Achaemenid religion.[54] Nyberg writes that there is no clear evidence as to when Zoroastrianism began to spread in Ray, the central base of Mughan. He believes that the latest time for this event was when the Achaemenid state was founded. He considered discussions and opinions on Achaemenid Zoroastrianism to be full of partisan prejudice and superstition among scholars of his time.[54]: 374

And add that in the basic structures of the Achaemenid religion, there is no specific term for the Zoroastrian community, no specific ideas of the type of gutas, and no specific belief or practice of the Zoroastrian religion.[55]

Jacques Duchesne-Guillemin wrote: “It seems easier to believe that the Achaemenids had never heard of Zoroaster, nor of his religious reforms".[14] Abdolhossein Zarrinkoob wrote: "In the Achaemenid era, the Magis did not have a Zoroastrian religion, nor did they have a royal family, considering the role that the Mongols played in performing Persian religious ceremonies, and considering that the Achaemenid and dynastic religion could not conflict with the beliefs of the common classes of the Persian clans. It is clear that the Zoroastrian religion had not yet had an influence among the Persians during these periods".[56]

See also

References

- ^ Henkelman, Wouter F. M. (2008). The other gods who are: studies in Elamite-Iranian acculturation based on the Persepolis fortification texts. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten. ISBN 978-90-6258-414-7. page. 353.

- ^ Henkelman, Wouter F. M. (2008). The other gods who are: studies in Elamite-Iranian acculturation based on the Persepolis fortification texts. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten. ISBN 978-90-6258-414-7. page. 374.

- ^ Henkelman, Wouter F.M. (2017). "Humban & Auramazdā: Royal Gods in a Persian Landscape". Persian Religion in the Achaemenid Period/La Religion Perse à l'époque Achéménide. Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 273–346. doi:10.2307/j.ctvckq50d.11. , page. 315

- ^ Henkelman, Wouter F. M. (2008). The other gods who are: studies in Elamite-Iranian acculturation based on the Persepolis fortification texts. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten. ISBN 978-90-6258-414-7. page. 353

- ^ Henkelman, Wouter F.M. (2017). "Humban & Auramazdā: Royal Gods in a Persian Landscape". Persian Religion in the Achaemenid Period/La Religion Perse à l'époque Achéménide. Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 273–346. doi:10.2307/j.ctvckq50d.11. page. 310.

- ^ Henkelman, Wouter F.M. (2017). "Humban & Auramazdā: Royal Gods in a Persian Landscape". Persian Religion in the Achaemenid Period/La Religion Perse à l'époque Achéménide. Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 273–346. doi:10.2307/j.ctvckq50d.11 page. 306.

- ^ Henkelman, Wouter F.M. (2017). "Humban & Auramazdā: Royal Gods in a Persian Landscape". Persian Religion in the Achaemenid Period/La Religion Perse à l'époque Achéménide. Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 273–346. doi:10.2307/j.ctvckq50d.11. page. 319

- ^ Henkelman, Wouter F.M. (2017). "Humban & Auramazdā: Royal Gods in a Persian Landscape". Persian Religion in the Achaemenid Period/La Religion Perse à l'époque Achéménide. Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 273–346. doi:10.2307/j.ctvckq50d.11. page. 313

- ^ Henkelman, Wouter F.M. (2017). "Humban & Auramazdā: Royal Gods in a Persian Landscape". Persian Religion in the Achaemenid Period/La Religion Perse à l'époque Achéménide. Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 273–346. doi:10.2307/j.ctvckq50d.11 page. 315–316.

- ^ Henkelman, Wouter F. M. (2008). The other gods who are: studies in Elamite-Iranian acculturation based on the Persepolis fortification texts. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten. ISBN 978-90-6258-414-7. page. 374.

- ^ Henkelman, Wouter F. M. (2008). The other gods who are: studies in Elamite-Iranian acculturation based on the Persepolis fortification texts. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten. ISBN 978-90-6258-414-7. page. 364.

- ^ Benveniste, Émile. دین ایرانی بر پایهٔ متنهای مهم یونانی [Iranian Religion: Based on important Greek texts]. Translated by سرکاراتی, بهمن. Tehran: انتشارات بنیاد فرهنگ ایران. pp. 31–36.

- ^ کاشانی. مجموعهٔ سخنرانیهای دومین کنگرهٔ تحقیقات ایرانی [Collection of Lectures of the Second Iranian Research Congress]. p. 224.

- ^ a b Yamauchi, Edwin Masao. ایران و ادیان باستانی [Iran and Ancient Religions]. Translated by Pezez, Manouchehr. Tehran: Atharan Qoqnoos.

- ^ William W. Malandra (1983). An Introduction to Ancient Iranian Religion: Readings from the Avesta and Achaemenid Inscriptions. U of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-1114-0. in the Achaemenid Empire.

- ^ Pierre Briant (2002). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Eisenbrauns. pp. 252–. ISBN 978-1-57506-120-7.

- ^ M. A. Dandamaev (1989). A Political History of the Achaemenid Empire. Brill. pp. 97–. ISBN 978-90-04-09172-6.

- ^ A. D. H. Bivar (1998). The Personalities of Mithra in Archaeology and Literature. Bibliotheca Persica Press. ISBN 978-0-933273-28-3.

- ^ Philippa Adrych; Robert Bracey; Dominic Dalglish; Stefanie Lenk; Rachel Wood (2017). Images of Mithra. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-251111-9.

- ^ Jean Perrot (2013). The Palace of Darius at Susa: The Great Royal Residence of Achaemenid Persia. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-84885-621-9.

- ^ Juri P. Stojanov; Yuri Stoyanov (11 August 2000). The Other God: Dualist Religions from Antiquity to the Cathar Heresy. Yale University Press. pp. 77–. ISBN 978-0-300-08253-1.

- ^ Baumer, Christoph (18 April 2018). History of Central Asia, The: 4-volume set. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 146. ISBN 978-1-83860-868-2.

- ^ Li, Xiao (10 September 2020). Studies on the History and Culture Along the Continental Silk Road. Springer Nature. p. 94. ISBN 978-981-15-7602-7.

- ^ Li, Xiao (10 September 2020). Studies on the History and Culture Along the Continental Silk Road. Springer Nature. p. 96. ISBN 978-981-15-7602-7.

- ^ «جلوه های باروری در هنر دوره ساسانی با تاکید بر نقوش ظروف فلزی» (PDF). ۲۰۱۷-۰۳-۱۷. دریافتشده در ۲۰۲۲-۱۱-۱۱.

- ^ a b c Shenkar 2014, p. 128.

- ^ Francfort 2012, p. 129.

- ^ Boyce & Grenet 1991, pp. 179–180.

- ^ a b Litvinskii & Pichikian 1994, p. 57.

- ^ Boyce & Grenet 1991, p. 173.

- ^ Boyce & Grenet 1991, p. 174.

- ^ Shenkar 2014, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Litvinskii & Pichikian 1994, p. 47.

- ^ Litvinskii & Pichikian 1994, p. 55.

- ^ (en) H. Koch, « Theology and Worship in Elam and Achaemenid Iran », dans J. M. Sasson (dir.), Civilizations of the Ancient Near East, New York, 1995, p. 1967-1969

- ^ S. Razmijou, « Religion and Burial Customs », dans Curtis et Tallis (dir.) 2005, p. 150-151.

- ^ Krul, Julia (2018). The Revival of the Anu Cult and the Nocturnal Fire Ceremony at Late Babylonian Uruk. Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004364943. ISBN 9789004364936.

- ^ Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2003). The Pantheon of Uruk During the Neo-Babylonian Period. Leiden Boston: Brill STYX. ISBN 978-90-04-13024-1. OCLC 51944564.

- ^ Krul, Julia (2018). The Revival of the Anu Cult and the Nocturnal Fire Ceremony at Late Babylonian Uruk. BRILL. doi:10.1163/9789004364943_004. ISBN 9789004364936.

- ^ George, Andrew R. (1993). House most high: the temples of ancient Mesopotamia. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 0-931464-80-3. OCLC 27813103

- ^ George, Andrew R. (1993). House most high: the temples of ancient Mesopotamia. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 0-931464-80-3. OCLC 27813103

- ^ George, Andrew R. (1993). House most high: the temples of ancient Mesopotamia. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 0-931464-80-3. OCLC 27813103

- ^ Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2003). The Pantheon of Uruk During the Neo-Babylonian Period. Leiden Boston: Brill STYX. ISBN 978-90-04-13024-1. OCLC 51944564

- ^ Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2003). The Pantheon of Uruk During the Neo-Babylonian Period. Leiden Boston: Brill STYX. ISBN 978-90-04-13024-1. OCLC 51944564.

- ^ Krul, Julia (2018). The Revival of the Anu Cult and the Nocturnal Fire Ceremony at Late Babylonian Uruk. BRILL. doi:10.1163/9789004364943_004. ISBN 9789004364936.

- ^ Asher-Greve, Julia M.; Westenholz, Joan G. (2013). Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources (PDF). Academic Press Fribourg. ISBN 978-3-7278-1738-0.

- ^ Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (1995). "Theological and Philological Speculations on the Names of the Goddess Antu". Orientalia. 64 (3). GBPress - Gregorian Biblical Press: 187–213. ISSN 0030-5367. JSTOR 43078085. Retrieved 2023-04-03.

- ^ Krul, Julia (2018). The Revival of the Anu Cult and the Nocturnal Fire Ceremony at Late Babylonian Uruk. BRILL. doi:10.1163/9789004364943_004. ISBN 9789004364936.

- ^ Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2003). The Pantheon of Uruk During the Neo-Babylonian Period. Leiden Boston: Brill STYX. ISBN 978-90-04-13024-1. OCLC 51944564.

- ^ Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2003). The Pantheon of Uruk During the Neo-Babylonian Period. Leiden Boston: Brill STYX. ISBN 978-90-04-13024-1. OCLC 51944564.

- ^ Krul, Julia (2018). The Revival of the Anu Cult and the Nocturnal Fire Ceremony at Late Babylonian Uruk. BRILL. doi:10.1163/9789004364943_004. ISBN 9789004364936.

- ^ Asher-Greve, Julia M.; Westenholz, Joan G. (2013). Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources (PDF). Academic Press Fribourg. ISBN 978-3-7278-1738-0.

- ^ Drewnowska-Rymarz, Olga (2008). Mesopotamian goddess Nanāja. Warszawa: Agade. ISBN 978-83-87111-41-0. OCLC 263460607.

- ^ a b Nyberg, Henrik Samuel (1359). Religions of ancient Iran. Translated by Najmabadi, Saif al-Din. Tehran: Iranian Center for the Study of Cultures.

- ^ نیبرگ، هنریک ساموئل (۱۳۵۹). دینهای ایران باستان. ترجمهٔ سیفالدین نجمآبادی. تهران: مرکز ایرانی مطالعهٔ فرهنگها.

- ^ Zarrinkoob, Abdolhossein. تاریخ مردم ایران، ایران قبل از اسلام. pp. 195–196.