The Montchanin coal mines were collieries that operated between 1820 and 1913 in the commune of Montchanin and several neighboring communes in Saône-et-Loire, central-eastern France.

Two concessions (Montchanin and Longpendu) were granted, before being merged in 1866 and acquired by Schneider et Cie in 1869. Mining at Montchanin enjoyed two periods of prosperity (1849-1864 and 1875-1885), before declining and collapsing at the beginning of the 20th century. The total production of the deposit, which belongs to the Blanzy coalfield, amounts to 7 million tons.

At the beginning of the 21st century, several remnants remain, including slag heaps, partially open shafts, ventilation shafts, and ruins of mining buildings.

Location

The Montchanin and Longpendu coalfield is an extension of the Blanzy coalfield, located in the communes of Montchanin, Le Breuil, Écuisses, Saint-Eusèbe, and Torcy, in the center of the Saône-et-Loire department,[1] in the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region of eastern France.

The operated area of the two concessions at Longpendu and Montchanin covers a total surface area of 25 km².[1]

A total of seven sectors are exploited: Bois des fauches, La Motte, and La Marquise in the northeast; Parc avril, Quétel-Les Ecrasées, and Gare-Ravarde in the center; Les Mésarmes and the Wilson sector in the southwest.[2]

Geology

The Montchanin coal mines exploit part of the long Blanzy-Le Creusot coalfield, of which it forms the eastern flank. The basin was formed in the Stephanian period (between 307 and 299 million years ago, Lower Carboniferous) in a trough in the granitic terrain, which allowed the accumulation of plant debris and was covered by Permian sediments. The strata are highly faulted, trending northeast-southwest. The dip varies constantly but averages 40–45° to the north.[3][4]

The disruption of the layers at Montchanin forms clusters of varying sizes and gradients. The largest on the concession is 60 meters thick and 600 meters long.[4] The Longpendu concession is located at the eastern end of the deposit, where the seven layers are thinner (1 to 3 meters for the six mined layers), farther apart, and faulted.[5][4]

History

Montchanin concession

The Montchanin coal outcrops were discovered by shepherds in 1792. The discovery was confirmed in 1825 when a navigable channel was dug between Torcy and the Canal du Centre.[6] That same year, Mr. Wilson, in association with the Manby et Cie company (both foundries in Le Creusot),[7] applied to the mayor of Saint-Eusèbe for authorization to sink a prospecting well at Les Brosses. Sinking of the Wilson shaft began in 1828, 93 meters below the navigable channel. At the same time, the Gattoux shaft was sunk to a depth of 42 meters. Simply timbered, the shaft column collapsed in 1837 before being bricked up. In 1832, the Neuf, de la Machine, and des Anglais shafts were sunk near the Wilson shaft. The former encountered coal at depths of between 5.5 and 76 meters. The Quétel shaft was sunk in 1833, extending the mine to the northeast with the discovery of a 70-metre-high, 600-metre-long seam. As the pumps of the time were inadequate, the Wilson shaft was regularly drowned, and several smaller shafts were dug in response to flooding and to identify the extension of the layers.[8][4]

In 1834, the concession was exploited by three main shafts no more than 200 meters deep: the Wilson shaft to the southwest, the Quétel shaft in the center, and the Longpendu shaft to the northeast. In 1838, the Montchanin concession was separated from that of Le Creusot. The operating company became the Société des houillères de Montchanin. In 1847, the shafts were deepened and the galleries systematically logged and backfilled. New shafts were sunk: the Sainte-Barbe de Montchanin shaft (1853), the Wilson no. 2 shaft (1855), the La Grille shaft (1856), and the Rigole shaft (1861).[8][4]

Longpendu concession

The 710-hectare Longpendu concession was granted to Madame de Montaigu by royal decree in 1832.[4] In 1838, the first work was carried out by the civil company created by the Marquise de Montaigu and Messrs Berger, de Chatelus, Giroux, and Gros.[4] The first sunken wells were the Voisottes well, the Chêne Fredin well, the descenderie well and the Étang well. The Baptiste shaft allowed some work to be carried out at the edge of the Creusot concession but was soon abandoned. Two twin wells, named Marie and Louise, were dug in 1834. Due to a strong inflow of water, sinking was suspended to allow the shaft columns to be walled up. Once completed, these two wells enabled a sharp increase in production.[4] The Grand Puits were sunk after 1840 to support the twin wells, with work starting on stages 50 and 60. In 1853, the Sainte-Barbe de Longpendu shaft was darkened and bricked up to complete the extraction system.[4] In 1855, the concession was taken over by Mr. Mangini, who deepened the Louise shaft to 198 meters to follow the sinking layers.[9][4]

Merger of the concessions

The two concessions were merged by decree in 1866.[4] The Montchanin concession and the Quétel cluster show signs of exhaustion. Director Charles Avril took advantage of the merging of the concessions to relaunch activity at Longpendu, with both mining and exploration campaigns proving fruitful.[9][4]

In 1869, the Schneider et Cie company acquired the concessions and launched new works: the sinking of the Mésarmes well to the south-west of the Wilson well, the sinking of the Saint-Vincent well (completed in 1875), and the relaunching of the Bois well.[4] In Longpendu, the Ravarde pond was drained to allow mining operations to extend towards the PLM station and the Saint-Martin shaft.[4] The work extends in a north-easterly direction to the Dressants area, where the coal beds are straightened by faults.[9][4]

- The main shafts of the second half of the 19thth century century.

-

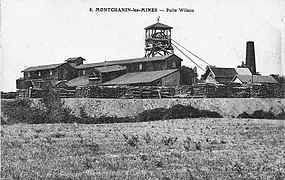

Wilson Shaft.

-

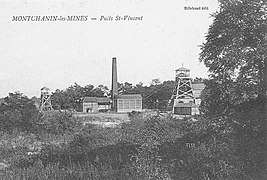

Longpendu Shaft.

-

Saint-Vincent Shaft.

New exploration campaigns were launched in 1879, just as mining was reaching its peak.[4] In 1893, a coal seam was identified at a depth of 27 meters on the edge of the Fauches concession, northeast of Longpendu, and several exploratory shafts were dug: the Montaigu shaft and the Fauches shaft.[4] In the end, the results were disappointing and the area was abandoned. At the same time, two sectors of the Montchanin concession were being exploited: Wilson-Soret-Mésarmes and Quétel-Saint-Vincent.[4][9][10]

Production declined steadily, reaching an average of 50,000 tonnes a year around 1907-1908.[4] The Le Creusot company decided to revive production with new works. With the Quétel heap exhausted, the focus shifted to Longpendu: the Grand Puits and the Sainte-Barbe de Montchanin wells were used for extraction, while the column of the Louise well was too damaged to be used for ventilation.[4] The Sainte-Barbe de Longpendu shaft was refurbished and equipped for extraction. However, the cost of this work was deemed too high, the deposit was depleted and financial losses accumulated, which is why the Longpendu mine closed in September 1912 and the Montchanin mine in May 1913.[4] Schneider et Cie attempted a final unsuccessful search for a mineable layer between 400 and 600 meters (as at Blanzy), before renewing its application to relinquish the concession in July 1914. The waiver was finally granted in 1944.[10][4]

- The last wells in 1912

-

The Sainte-Barbe well in Montchanin.

-

Sainte-Barbe plan.

-

Well of the Mesarmes.

-

Sôret Well.

Works

A total of 85 mining structures have been identified for the two concessions, including 66 mine shafts and ventilation shafts, 15 drifts, and four gallery entrances.[4] The majority of extraction shafts and ventilation shafts are shallow (less than 80 meters), whereas the few main shafts (20% of mine shafts) systematically exceed 100 meters in depth, the deepest being the Saint-Vincent shaft (720 meters).[4] As the terrain is not very steep, hillside galleries are rare and vertical or steeply inclined access is required to bring the coal up from the mine.[11][4]

Mining began in the southwest of the deposit, with the Wilson and Mésarmes shafts, and gradually moved north-eastwards.[4] Mining was particularly intense in the center of the concession, where the Quétel pile (the largest) was located and was mined from 1833 to 1911.[4] In the 1890s, areas stripped around 1860 and 1870 were once again mined. By the 1900s, the Quétel cluster was no longer meeting demand, and mining was redirected to the southwest, in a cluster located between the Soret and Mésarmes shafts.[4] The lack of technical resources to ensure mine drainage and aeration, combined with a lack of knowledge of the deposit, led managers to mine coal at shallow depths in the early days of the business, before gradually deepening the workings to 250 meters at Montchanin and 380 meters at Longpendu.[10][4]

In the early days, large deposits were mined by horizontal slabbing, while smaller layers were mined by drifting and recutting. After several mine fires, the operators decided to immediately and systematically backfill the finished workings as mining progressed.[12][4]

Gratoux well

The Gratoux well was dug to a depth of 42 meters in 1826, following research carried out in 1825. It was resumed in 1837 to a depth of 119 meters and suffered a cave-in in December 1837.[7]

La Machine well

In 1834, the Machine shaft was powered by a 12-hp steam engine. This was refurbished in 1838 when the shaft was some forty meters deep. A new boiler was installed the following year. In 1844, the well was still in operation, at a depth of around 80 meters.[7]

Ségur well

The extraction site existed before 1860 and comprised two shafts: Ségur no. 1 (134.7 meters) and Ségur no. 2 (509.85 meters). In 1894, the site was used for ventilation.[7]

Quétel well

The Quétel well was sunk in 1833 as an annex to the Neuf well. The site comprises two shafts: Quétel no. 1 (94.5 meters) and Quétel no. 2 (43 meters). Built of masonry throughout, it is used for both extraction and ventilation. In 1847, it was equipped with a 12-hp steam engine.[7]

In 1894, it was used exclusively for ventilation. In January 1898, it was equipped with a 10 hp engine. In 1909, it replaced the Saint-Vincent shaft for ventilation after the latter's guide cables broke. But the Quétel shaft suffered the same damage. Demolition of the installations was completed in October 1913.[7]

Neuf well

The Neuf well was sunk in 1835 or 1828 to a depth of 58 meters, and is equipped with a 16 hp steam engine that could also be used at the Quétel well. It was used for coal extraction and waste rock disposal in the 1830s and 1840s.[7]

North well

The North well was in operation in the 1840s.[7]

Saint-Vincent well

The Saint-Vincent well was sunk to a depth of 709.55 meters in 1875. In 1894, it was used for water extraction and drainage. It was equipped with a coal washing and screening plant. In 1898, it was equipped with a 40-hp steam engine. A break in the guide cables put an end to mining in 1909. It was stripped and backfilled in 1912. Demolition of the installations was completed in October 1913.[7]

Wilson well

The Wilson no. 1 shaft was sunk in 1826 or 1831 to a depth of 93 meters and was bricked up. The building and chimney for the 16-hp steam engine were completed in 1838. Shaft no. 1 was subsequently deepened to 230.65 meters.[7]

Wilson shaft no. 2 (197.30 m) was sunk in 1854.[7]

In 1894, it was used for extraction and dewatering. It was equipped with a coal washing and screening plant. In 1898, it was equipped with a 40-hp engine, a 3-hp pump, and a forge. Demolition was completed in October 1913.[7]

- The Wilson Well tile

-

The Wilson shaft of the Montchanin coal mines.

-

The Wilson shaft of the Montchanin coal mines.

Les Mésarmes well

In 1898, the Mésarmes well was equipped with a 40-hp steam engine. Research was carried out in 1908 and 1909 to revive mining. The 212.15-meter shaft was deemed to be in poor condition and backfilled. Demolition of the installations was completed in October 1913.[7]

Soret well

30 hp steam engine.[7]

Saint-Martin well

Sinking of the Saint-Martin well began in 1839, but was interrupted in 1840 at a depth of 45 meters. Digging resumed in 1843 and was completed at a depth of 80 meters.[7]

Bois well

16-hp steam engine.[7]

La Grille well

The Rigole well was sunk in 1856.[8] It collapsed in 1908. Demolition was completed in October 1913.[7]

Rigole well

The Rigole well was sunk in 1861[8] and is 184.60 meters deep.[7]

La Ronce well

The Ronce well is 43 meters deep.[7]

Great well / Longpendu well

In 1834, the Longpendu well was one of the three main wells.[8] The Great well was sunk after 1840 to support the twin shafts, with work starting in the 50s and 60s.[9] In the 1900s, it was one of the main extraction shafts.[10]

- The tile from the Longpendu well

-

The Longpendu well of the Montchanin coal mines.

-

The Longpendu well of the Montchanin coal mines.

-

The Longpendu well of the Montchanin coal mines.

Sainte-Barbe de Montchanin well

The Sainte-Barbe de Montchanin well was sunk in 1853.[8] After a period of abandonment, it was relaunched in 1907, receiving the old Saint-Pierre well extraction machine from Le Creusot. A metal headframe was built by the Schneider workshops in Chalon-sur-Saône. In 1910, compressors were installed to supply compressed air.[7]

Sainte-Barbe de Longpendu well

The Sainte-Barbe de Longpendu well was commissioned in 1853, after being darkened and bricked up.[9]

Twin wells (Marie and Louise)

The twin wells, named Marie and Louise, were dug in 1834. Due to a strong inflow of water, sinking was suspended to allow the well columns to be walled up. In 1855, Mr. Mangini had the Louise well deepened to 198 meters to follow the sinking layers.[9] Around 1907-1908, the Louise shaft column was too badly damaged, so it was used only for ventilation.[10]

Extraction from the twin shafts reached 350 hl per day.[13]

Boulogne well

The Boulogne well is 70 meters deep.[7]

Anglais well

The Anglais well is 80 meters deep.[7]

Production

Total production from the Montchanin and Longpendu concessions is estimated at 7 million tons of coal. The Montchanin concession reached its peak between 1875 and 1885 before production gradually declined. It mined a total of around 4 million tonnes, including 3 million from the Quétel pile. The prosperity of the Longpendu concession dates back further (1849-1864).[14]

| Before 1870 | 1870-1875 | 1875-1880 | 1880-1885 | 1885-1890 | 1890-1895 | 1895-1900 | 1900-1905 | 1905-1911 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average annual production (in thousand tons) |

NC | 114.9 | 147.4 | 143 | 103 | 87 | 82 | 61 | 52 |

| 1839-1849 | 1849-1864 | 1866 | 1868 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average annual production (in thousand tons) |

120 | 380 | 10 | 25 |

Other activities

The Montchanin company diversified its activities into coal-consuming or coal-processing production tools, such as lime kilns in 1857, a steam sawmill in 1861, a briquette-agglomerating plant, and a coal preparation plant between 1860 and 1864.[7]

Social aspects

Workers' housing was specially built by the company for miners and their families as early as 1837. Two years later, a school was built, and a savings and loan cooperative were set up. In 1847, the construction of the church, the presbytery and the extension of the school were completed. In 1858, Château Avril, the principal's residence, was built. The Pisés housing estate was built in 1861.[7]

Disasters and accidents

Landslide

The “foudroyage” mining method was particularly dangerous, and was responsible for a number of individual accidents. One miner was killed for every 70,000 tons extracted. The switch to systematic backfilling reduced the number of fatalities to one for every 155,000 tons extracted.[15]

Gas and fire

The Montchanin coalfields are particularly susceptible to firedamp. Roof collapses led to underground fires.[15] Before 1850, fires broke out at various locations in the old workings. A fire temporarily put an end to operations at Longpendu. The smoke from these fires sometimes caused considerable disruption to nearby work sites. Backfilling the workings greatly reduced the frequency of these fires. By 1894, ventilation was sufficiently effective that firedamp was rare in Montchanin and non-existent in Longpendu.[13]

Flooding

Montchanin is surrounded by ponds, lakes, and canals. Concessionaires had to contend with water seepage throughout the mining season. Most wells were quickly flooded when sunk (Mésarmes, Wilson, Sainte-Barbe de Longpendu). The Marie and Louise shafts were abandoned due to heavy water inflows and had to be walled up to their full height to resume extraction. Extraction from these twin shafts reached 350 hl per day.[13]

Remains

At the beginning of the 21st century, most of the shafts had been backfilled and were no longer visible,[11] but several remnants, such as slag heaps, remained. Many wells, such as the funnel-shaped Puits de la Grille, or the Montaigu no. 1, Mésarmes, and Sainte-Barbe de Montchanin wells, have been compacted, revealing several meters of brick casing. The Soret and Lazare wells are closed by thin concrete slabs; the former is backfilled, but not the latter, which is just submerged. Ventilation shafts and ruins of mining buildings (Sainte-Barbe de Montchanin) also remain.[16][17]

-

The spoil heap of the La Grille well.

-

The funnel formed by the La Grille well.

-

Flooded secondary well of the La Grille well.

-

Montaigu well no. 1.

-

The Lazare well blocked by a concrete slab.

-

The opening of the Sainte-Barbe well in Montchanin.

-

The building of the extraction machine of the same well.

-

The ruins of Wilson's Well.

- Remains of the Mésarmes well

-

Ruins of the recipe building.

-

The well opening.

-

The underground access gallery.

-

Under-slag recipe.

See also

References

- ^ a b Descamps (2010a, p. 15)

- ^ Descamps (2010a, pp. 16–17)

- ^ Descamps (2010a, pp. 18–20)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Denimal et al. (2005)

- ^ Descamps (2010a, pp. 21–23)

- ^ Descamps (2010a, p. 23)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x "Concession de montchanin" [Montchanin concession]. Histoire de montceau (in French). Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Descamps (2010a, p. 24)

- ^ a b c d e f g Descamps (2010a, p. 25)

- ^ a b c d e Descamps (2010a, p. 26)

- ^ a b Descamps (2010a, p. 32)

- ^ Descamps (2010a, p. 29)

- ^ a b c Descamps (2010a, p. 31)

- ^ a b c Descamps (2010a, pp. 28–29)

- ^ a b Descamps (2010a, p. 30)

- ^ Descamps (2010a, p. 33)

- ^ Descamps (2010b, Annexe 4 : Planches Photographiques)

Bibliography

- Descamps, Mandy (2010a). Bassin houiller de Blanzy - Concessions de Montchanin et Longpendu : Évaluation et cartographie des aléas liés aux mouvements de terrains [Blanzy coal basin - Montchanin and Longpendu concessions: Assessment and mapping of hazards linked to ground movements] (PDF) (in French). Vol. 1. INERIS.

- Descamps, Mandy (2010b). Bassin houiller de Blanzy - Concessions de Montchanin et Longpendu : Évaluation et cartographie des aléas liés aux mouvements de terrains (planches annexes) [Blanzy coal basin - Montchanin and Longpendu concessions: Assessment and mapping of hazards linked to ground movements (annex plates)] (PDF) (in French). Vol. 2. INERIS.

- Denimal, Sophie; Mudry, Jacques-Noël; Paquette, Yves; Hochart, Magalie; Steinmann, Marc (2005). "Evolution of the aqueous geochemistry of mine pit lakes - Blanzy-Montceau-les-Mines coal basin (Massif Central, France): Origin of sulfate contents; effects of stratification on water quality". Applied Geochemistry. 20 (5): 825. Bibcode:2005ApGC...20..825D. doi:10.1016/j.apgeochem.2004.11.015. Retrieved February 6, 2025.