Ducal Palace, Mantua

| Palazzo Ducale di Mantova | |

|---|---|

The Magna Domus | |

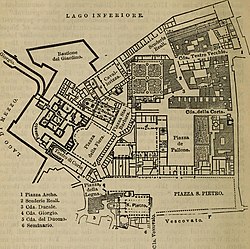

Interactive map of the Palazzo Ducale di Mantova area | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Renaissance |

| Location | Mantua, Lombardy, Piazza Sordello 40, Italy |

| Year built | 13th–18th century |

| Client | Bonacolsi, Gonzaga |

| Owner | Ministry of Culture |

Palazzo del Capitano | |

| |

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Type | Art |

| Collections | Paintings and sculptures |

| Director | Stefano L'Occaso |

| Owner | Ministry of Culture |

| Exhibition area | 34,000 m²[1] |

| Visitors | 346,462 (2019)[2] |

The Palazzo Ducale (Ducal Palace) in Mantua, also known as the Gonzaga Palace, is one of the city's main historic buildings. From 1308, it served as the official residence of the Lords of Mantua, initially the Bonacolsi, and later the main residence of the Gonzaga, who were lords, marquesses, and eventually dukes of the Virgilian city. It housed the reigning Gonzaga, his wife, their legitimate firstborn son, other legitimate children until adulthood, and notable guests.[3] It was designated the Royal Palace during the Austrian domination starting from the reign of Maria Theresa.

Each duke sought to add a wing for themselves and their art collections, resulting in an area exceeding 35,000 m², making it one of Europe's largest palaces[4] after the palaces of the Vatican, the Louvre Palace, the Palace of Versailles, the Royal Palace of Caserta, the Royal Palace of Venaria, Buckingham Palace, the Palace of Fontainebleau, the Winter Palace, or the Royal Palace of Stockholm. It comprises over 500 rooms[5] and encompasses 7 gardens and 8 courtyards.[6]

History

Bonacolsi and Gonzaga Period

Distinct and separate spaces were constructed in different eras starting from the 13th century, initially by the Bonacolsi family and later under the impetus of the Gonzaga. Duke Guglielmo commissioned the Surveyor of Works, Giovanni Battista Bertani, to connect the various buildings organically, creating, from 1556, a single monumental and architectural complex, one of the largest in Europe (approximately 34,000 m²[1]), stretching between the shore of Lake Inferiore and Piazza Sordello, the ancient Piazza San Pietro. After Bertani's death in 1576, the work was continued by Bernardino Facciotto, who completed the integration of gardens, squares, loggias, galleries, exedras, and courtyards, definitively shaping the ducal residence.

Over the four centuries of Gonzaga rule, the palace gradually expanded through new constructions and modifications of existing structures.[7] Several nuclei emerged, named:

- Corte Vecchia, encompassing the oldest buildings facing Piazza Sordello

- Domus Nova, built by Luca Fancelli

- Corte Nuova, facing the lake, constructed by Giulio Romano and later expanded by Bertani and Viani

- Palatine Basilica of Santa Barbara, built by Bertani.

The complex also included some demolished buildings and courtyards, such as the Palazzina della Paleologa (demolished in 1899) and the Court Theater.

The palace's interior is largely bare due to financial difficulties that led the Gonzaga, starting with Duke Ferdinando, to sell artworks (especially to Charles I of England) and furnishings. Further losses occurred during the Sack of Mantua in 1630 and through removals by the last duke, Ferdinando Carlo Gonzaga, who fled to Venice in 1707.

Habsburg period

Under the imperial governor Philip of Hesse-Darmstadt in 1716, the palace was partially refurnished with paintings, sculptures, and furnishings from the former ducal residences of the Pico in Mirandola, whose last duke, Francesco Maria II, was declared deposed for “treason” by Emperor Joseph I in 1706.

Having lost its role as a multifunctional court serving the ruling family, the palace was stripped of its functions and significance throughout the Habsburg and French dominations, and again until the end of Austrian rule in 1866. It increasingly served military purposes as a cornerstone of the fortress that Mantua had become. Among the spaces used for military purposes was almost the entire Castello di San Giorgio, which the Austrian authorities also used as a prison, where Italian patriots, including some of the Belfiore martyrs, were incarcerated.

Ducal Palace Museum

With Mantua's annexation to the Kingdom of Italy, the palace became part of the National Heritage. In 1887, the "monumental part" of the architectural complex that had formed the Gonzaga court was taken over by the Ministry of Public Education, enabling the first public visits to the palace that same year. The museum function can be dated to October 10, 1887, when a regular daily visitor register was established, albeit for non-paying visitors.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the palace underwent a major restoration project, particularly focusing on medieval structures: the Palazzo del Capitano, the Magna Domus, and the Castello di San Giorgio.[8] Alongside economic support from the Municipality and Province, the Society for the Palazzo Ducale, a philanthropic association founded in 1902, contributed to these restoration efforts.[8]

On March 11, 1915, a convention was signed between the State and local institutions to establish the Museum in the Palazzo Ducale di Mantova. The act recognized and confirmed the ownership of artworks by the Municipality or the Accademia Nazionale Virgiliana di Scienze Lettere ed Arti, but allowed their placement in the rooms of the Gonzaga palace, the most prestigious complex for their display and enjoyment by the emerging cultural tourism.

In the 20th century, numerous donations and bequests enriched the collection, including those from Annibale Norsa (1916), Virgilio Scarpari Forattini (1921–1924), Maria Ottolini and Mario Musante (1955), Eleonora Cibele Buris (1958), Ugo Dolci (1959), and Nerina Mazzini Beduschi (1968).[9]

In the 21st century, the monumental complex of Palazzo Ducale was struck by unusually intense seismic events. The 2012 Emilia earthquakes initially caused damage to several rooms of the Gonzaga palace (Sala di Manto, Galleria dei Mesi, Corridoio del Bertani). The palace, closed from May 20, 2012,[10] was later partially reopened to tourists, requiring significant restoration work in Corte Nuova, the wing most affected by the tremors. The damage from the May 29 tremors was more severe, exacerbating earlier cracks, affecting the bell tower of the Palatine Basilica of Santa Barbara, and marginally damaging the famous Camera degli Sposi by Andrea Mantegna in the Castello di San Giorgio.[11]

Following the consolidation work on the Castello di San Giorgio, the Camera degli Sposi was reopened to visitors on April 3, 2015. Simultaneously, the collection of Mantuan industrialist Romano Freddi was displayed on loan, comprising about a hundred Gonzaga-era works, including a panel by Giulio Romano and his pupils and a fragment of the altarpiece The Gonzaga Family in Adoration of the Holy Trinity by Rubens, depicting Francesco IV.[12]

Visitors

In 2011, Palazzo Ducale had 220,143 visitors,[13] which dropped to 160,634 in 2012[14] due to the seismic events of May 20 and 29, which necessitated a reduced visiting route excluding the Castello di San Giorgio and the Camera degli Sposi. By the end of June 2016, during "Mantua Italian Capital of Culture 2016," visitors had nearly reached 200,000.[15] By the end of 2016, 367,470 visitors were recorded.[2] In 2023, approximately 287,000 visitors were recorded.[16]

The complex

The architectural ensemble of Palazzo Ducale is striking for its size (35,000 m² with over 1,000 rooms) and the complexity of its interconnected corridors, earning it the name "city-palace."

Corte Vecchia

Corte Vecchia is the oldest core of the palace, comprising the medieval buildings of the Palazzo del Capitano and the Magna Domus facing Piazza Sordello.

Palazzo del Capitano and Magna Domus

The Palazzo del Capitano is the oldest building in Palazzo Ducale, commissioned by Guido Bonacolsi at the end of the 13th century. Initially built with two floors and separated from the Magna Domus by an alley, it was raised by one floor in the early 14th century and connected to the Magna Domus by a monumental portico facade, which remains largely unchanged today. The added second floor consists of a single vast hall (67x15 m) called the Hall of the Armory, also known as the Hall of the Diet, as it hosted the Diet of Mantua in 1459. This distinguished space is currently abandoned and in need of restoration.

The Pisanello Cycle

Antonio Pisano, known as Pisanello, painted a grand cycle of Arthurian-themed chivalric frescoes between 1433 and 1437 in the room now named after him, depicting the Battle of Louverzep, intended to glorify the patron Gianfrancesco Gonzaga, who is also depicted in the artwork. These frescoes narrate the epic tale of King Arthur, whose stories were highly popular at the time as they embodied the ideals of chivalric behavior.

This fresco cycle was never completed for unknown reasons.[17] The frescoes were covered by the late 16th century with faux marble decorations and in 1701 with a frieze featuring portraits of the Gonzaga from the first Luigi to the last Ferdinando Carlo, leading the room to be called the Hall of the Princes. Around 1810, further neoclassical updates were added above the frieze.[18] The frescoes were rediscovered and restored between 1965 and 1970, thanks to superintendent Giovanni Paccagnini, who intuited the presence of a significant pictorial cycle from traces visible in the attic.[18] Today, the Pisanello rooms house fragments of the frescoes and their preparatory sinopie.

Apartment of Isabella d'Este in the Corte Vecchia

Corte Vecchia regained prominence when Isabella d'Este moved from the Castle in 1519 to the ground floor of this ancient sector of the Gonzaga palace, in the so-called widow’s apartment. Isabella’s apartment consisted of two wings, now divided by the entrance to the Courtyard of Honor. In the more private Grotta wing, she brought wooden furnishings and art collections from her two famous studioli, the grotta and the studiolo. The latter contained paintings, now housed in the Louvre Museum, commissioned between 1496 and 1506 from Mantegna (Parnassus and Triumph of the Virtues), Lorenzo Costa (Isabella d'Este in the Kingdom of Harmony and Kingdom of Como), and Perugino (The Battle Between Love and Chastity), along with works by Correggio (Allegory of Vice and Allegory of Virtue). Another notable space in this wing is the "Camera Granda" or "Scalcheria," frescoed in 1522 by the Mantuan Lorenzo Leonbruno. The apartment also included other rooms in the wing called "Santa Croce,"[19] named after an ancient church from Matilda’s era, on whose remains reception rooms were built, such as the Hall of Isabella's Deeds, the Imperial Hall or Fireplace Hall, the Hall of Marigolds, the Hall of Plaques, and the Hall of Deeds. The Secret Garden is also an integral part of the Grotta Apartment.

Santa Croce Vecchia was a small church, typical of the period around the year 1000. Its existence is documented by a record from May 10, 1083, signed by Matilda of Canossa. Adjacent to the earliest buildings of the future Palazzo Ducale, it likely served as the palatine church of the Bonacolsi and Gonzaga. However, the Gonzaga’s well-known passion for construction led to the demolition of the ancient Matilda-era church. Authorized by Pope Martin V, Gianfrancesco Gonzaga demolished the old church around 1421 and built a late Gothic chapel with the same dedication nearby, now deconsecrated but still identifiable by the small courtyard accessing Isabella d’Este’s widow’s apartment.

Later, Guglielmo Gonzaga (1550–1587) transformed Corte Vecchia’s spaces, creating the Refectory overlooking the Hanging Garden and the Hall of Mirrors, intended for music.

Hall of Rivers, Tapestry Room, Hall of the Zodiac

During the Habsburg period, the Refectory was renovated, resulting in the Hall of Rivers, where Giorgio Anselmi painted (circa 1775) giants representing the rivers of the Mantuan territory on the walls.

Concurrently, the Tapestry Apartment was created, consisting of four rooms. Three of these have walls adorned with nine handwoven tapestries from Flanders, based on preparatory cartoons by Raphael, the same used for the famous Raphael Cartoons preserved in the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City. Purchased in Brussels by Cardinal Ercole Gonzaga around 1552 to furnish what was then called the "Green Apartment," the tapestries were bequeathed in his 1563 will to his nephew Guglielmo, with the wish that they adorn the Palatine Basilica of Santa Barbara, where they remained for two centuries. Forgotten in the palace’s storerooms, they were restored in 1799 and placed in the apartment adapted for them.

The Hall of the Zodiac, Guglielmo Gonzaga’s private apartment, was painted between 1579 and 1580 by Lorenzo Costa the Younger with assistance from Andreasino. Today, only the frescoed ceiling remains, as the walls were redecorated in the Napoleonic era. The room is also called Napoleon I’s Room, as it served as Bonaparte’s bedroom. The vault depicts the chariot of Diana pulled by dogs among the constellations of the Zodiac, with the constellation of Astrea at the center near Diana’s chariot, interpreted as an allusion to the Duke’s horoscope. The krater (cup) of sacrifices and libations symbolizes the immortality of the Gonzaga lineage. The Raven, a bird sacred to Apollo, was transformed into a constellation by the god. The Virgo sign, holding a wheat ear, takes the form of Astrea and Ceres and is the emblem of Vincenzo Gonzaga. The firmament revolves around Diana’s chariot, drawn by a pack of dogs. The goddess, depicted as pregnant, represents Eleanor of Austria, wife of the Duke of Mantua. According to ancient tradition, Scorpio holds the Libra sign in its claws.[20]

The ceiling’s large surface is painted with the oil-on-plaster technique, and the vault is ribbed. The current neoclassical appearance of the walls, decorated with gilded candelabra in neo-Egyptian motifs (by Gerolamo Staffieri) dates to the Napoleonic period (1813). Above the doors are four stucco panels imitating bronze, depicting allegories: i) Napoleon receives the sword of Mars from Jupiter, ii) Italy offers the Laws to Napoleon, iii) Napoleon accepts the products of the earth, iv) Minerva presents the arts and sciences to Napoleon.

Guastalla Apartment

Located on the upper floor of the Palazzo del Capitano, it is named after Anna Isabella Gonzaga[21] from Guastalla, wife of the last duke Ferdinando Carlo Gonzaga. It comprises six rooms (including the Hall of Emperors) with wooden ceilings, partially modified in the late 16th century. Traces of 14th-century frescoes remain on the walls. Among the exhibited works is the tombstone of Alda d’Este in marble, created in 1381 by Bonino da Campione. From the early 19th century, the sculpted figure was mistakenly thought to be Margherita Malatesta.[22]

The apartment is flanked by the long Passerino Corridor, where the mummy of Passerino Bonacolsi, ousted by the Gonzaga in 1328, was reportedly kept.

Empress’s Apartment

Comprising nine rooms furnished in the Empire style, it is located on the first floor of the Magna Domus. It was arranged in 1778 for Maria Beatrice d’Este, wife of Ferdinand Karl, the fifth son of Maria Theresa, hence its name derived from the imperial Habsburg connection. These rooms also hosted Prince Eugène de Beauharnais,[23] viceroy of the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy, who in 1810 brought from Milan a precious canopy bed adorned with fabrics from Lyon, still preserved in the bedroom, otherwise furnished with Habsburg-era furniture.

Guglielmo’s Apartment in Corte Vecchia

Comprising five rooms, including the Hanging Garden.

Other Rooms on the Piano Nobile of Corte Vecchia

- Morone Room, housing the painting Battle between the Gonzaga and the Bonacolsi by Domenico Morone (1494)

- Hall of the Popes

- Alcove Rooms

- New Gallery

- Ducal Chapel

- Hall of Mirrors, with decorations by Antonio Maria Viani

- Moors’ Corridor, with early 17th-century stucco decorations

- Moors’ Small Room, with a 1580 ceiling featuring a medallion with Venus and Cupids by Daniel van den Dyck, who served as Surveyor of the Gonzaga Works from 1657 to 1662[24]

- Falcons’ Room, with decorations from the second half of the 16th century

- Santa Barbara Loggia

Domus Nova

The Tuscan architect Luca Fancelli built the Domus Nova (1480–84), which, over a century later, under Duke Vincenzo I, underwent architectural interventions that transformed Fancelli’s building. This project, resulting in the current Ducal Apartment, was designed by the Cremonese painter and architect Antonio Maria Viani, who served the Gonzaga from 1595. In the grand Hall of the Archers, paintings from suppressed churches and monasteries are now displayed. The most famous work exhibited there is The Gonzaga Family in Adoration of the Holy Trinity by Peter Paul Rubens, created for the Church of the Holy Trinity in 1605. In Mantua, only the central canvas, partially mutilated, remains of the original triptych, with the Transfiguration of Christ now in Nancy and the Baptism of Christ in Antwerp. The Mantuan canvas depicts Duke Vincenzo and his wife Eleanor de' Medici in the foreground, with his father Guglielmo and his wife Eleanor of Austria in the background.

Ducal Apartment

Built by Duke Guglielmo Gonzaga around 1580 with carved and decorated ceilings, it was remodeled by architect Antonio Maria Viani during the time of Vincenzo I.[25] It includes the following rooms:

- Hall of Judith, with a ceiling depicting the Gonzaga deed of the "Crucible"; the room contains four large 17th-century canvases by the Neapolitan Pietro Mango, court painter of Charles II Gonzaga, depicting scenes from Judith’s life (Judith at Holofernes’ Camp, Holofernes’ Banquet, Judith Beheads Holofernes, The Display of Holofernes’ Head). Originally called the "Room of the Footmen", it now displays the series Christ and the Eleven Apostles, painted by Domenico Fetti around 1620.[26]

- Hall of the Labyrinth, with a ceiling, transferred from the Palazzo San Sebastiano, carved with a labyrinth and the motto of Marquess Francesco II Gonzaga "Perhaps yes, perhaps no", supplemented during its transfer to Palazzo Ducale with an inscription on the outer band commemorating the battle of Kanizsa in Hungary, where Vincenzo I Gonzaga fought the Turks;[25]

- Hall of the Crucible, with a ceiling featuring the motto Me probasti domine et cognovisti me;[25]

- Hall of Cupid and Psyche;

- Hall of Jupiter and Juno.

Eleanor de’ Medici or Ferdinando’s Apartment

Prepared for the wife of Vincenzo I, Eleanor de' Medici.[25] Also called the Paradise Apartment for its splendid lake view. It consists of ten rooms, including:

- Rooms of the Cities

- Cabinet of the Storks

- Room of the Four Elements

- Room of the Tiles

- Room of the Landscapes

Catacombs in the Court or Dwarfs’ Apartment

Duke Ferdinando Gonzaga, second son of Vincenzo, who was a cardinal before succeeding his brother Francesco III, commissioned Antonio Maria Viani to build the Scala Sancta in miniature, located under his apartment in the Domus Nova. These spaces replicate the original Scala Sancta in Rome at San Giovanni in Laterano on a reduced scale. This miniaturization led for centuries to the belief that these rooms were intended for the mythical Gonzaga dwarfs, also depicted in the Camera degli Sposi. Until 1979, this “apartment” was called the "Dwarfs’ Apartment", when scholar Renato Berzaghi debunked the historical misconception, demonstrating through archival documents the correspondence between the Gonzaga reproduction and the Roman original, identifying the area as the Catacombs in the Court.

Corte Nuova

Built in 1536 by architect Giulio Romano[27] for Duke Federico II Gonzaga and expanded by Bertani.

Grand Castle Apartment

The Grand Castle Apartment consists of six rooms.

Sala di Manto

The Sala di Manto is within Corte Nuova. Originally the entrance to the Troy Apartment, named after the frescoes in the main room by collaborators of Giulio Romano (Luca di Faenza) between 1538 and 1539, commissioned by Federico II Gonzaga to renovate numerous palace rooms. The current appearance of the Sala di Manto is due to Guglielmo’s creation of the Grand Castle Apartment. The frescoes depict the city’s founding, preceded by the arrival in Italy of Manto, the legendary daughter of the seer Tiresias. The birth of the city by her son Ocnus and other urban works undertaken by the Gonzaga are also portrayed. The frescoes are attributed to Francesco Primaticcio.

Apartment of Metamorphoses

Built in 1616 by Antonio Maria Viani, it is named for the ceiling decorations inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses.[25] Comprising four rooms dedicated to the four natural elements—earth, water, air, and fire—the apartment housed the Gonzaga family’s extensive library, which was lost during the Sack of Mantua in 1630, and the embalmed body of Rinaldo Bonacolsi, known as Passerino, killed in 1328 when the Gonzaga seized power in Mantua. Notably, Rinaldo’s body was displayed on a taxidermied hippopotamus, acquired by the Gonzaga in the early 17th century. Around 1700, Rinaldo’s mummy was thrown into the lake, and in 1783, the Austrian government transferred the hippopotamus to the Natural History Museum, where it is currently preserved.[28]

Rustica, Estivale, or Mostra Apartment

Commissioned by Federico II Gonzaga as a residence for distinguished court guests, the project and initial construction were carried out by architect Giulio Romano starting in 1539. The Rustica palace was completed by Giovan Battista Bertani around 1561.[25] It comprises seven rooms:

- Hall of the Loves of Jupiter

- Hall of the Two Columns

- Hall of the Consoles

- Hall of the Fruits

- Hall of the Four Columns

- Hall of the Fish

- Orpheus’ Small Room

Other Rooms in Corte Nuova

- Galleria della Mostra, with an imposing wooden ceiling, nearly 7 meters wide and 64 meters long, was built in the early 17th century by Giuseppe Dattaro on commission from Vincenzo I Gonzaga. The largest in the palace, it was intended to house the Gonzaga’s precious object collections.[29] A plaque inside the grand hall commemorates the American Henry Kress, who generously contributed to the Palazzo Ducale’s restoration in the early 20th century.[30]

- Hall of the Horses, with canvases celebrating the Gonzaga horses

- Rooms of the Heads

- Cabinet of the Caesars

- Gallery of the Marbles or Months, with genii and zodiac signs, an early work by Giulio Romano[27]

- Room of the Captains

- Room of the Marquesses, with sculptures of the Gonzaga marquesses and their wives by the Venetian Francesco Segala[31]

- Room of the Dukes, by Giovan Battista Bertani, which housed the Fasti of the Gonzagas commissioned by Guglielmo Gonzaga to Tintoretto,[32] now preserved at the Alte Pinakothek in Munich

Santa Barbara Corridor

Designed by Bernardino Facciotto around 1580, it provided a covered passage between Corte Nuova and Corte Vecchia. From the south side, the Gonzaga family could access the tribune of the adjacent Basilica of Santa Barbara. To the north, the corridor overlooks Piazza Castello.

Enea’s Staircase

A work by Bertani from 1549—shortly after being appointed "Surveyor of the Ducal Works" by Cardinal Ercole Gonzaga—it directly connects the Hall of Manto with the Castello di San Giorgio. At the end of the staircase, one accesses the castle’s courtyard and its loggia, a work by Luca Fancelli from 1472.[33]

Palatine Basilica of Santa Barbara

The court’s basilica was built between 1562 and 1572 on the decision of Duke Guglielmo Gonzaga, who entrusted the project to the ducal architect Giovan Battista Bertani. It was designed as the setting for the palace’s lavish liturgical ceremonies accompanied by sacred music, equipped with a precious Antegnati organ. The church was recently the site of a significant discovery: the remains of four dukes and other Gonzaga family members, including Guglielmo, who built Santa Barbara and transformed it into a Gonzaga pantheon.[34]

Castello di San Giorgio

Built from 1395 and completed in 1406 on the commission of Francesco I Gonzaga and designed by Bartolino da Novara.

Andrea Mantegna, summoned to Mantua in 1460 by Marquess Ludovico II and residing in the Virgilian city until his death in 1506, created his most famous and ingenious work within the Castello di San Giorgio, the Camera Picta or Camera degli Sposi.

Gardens and courtyards

- The Courtyard of the Cavallerizza, also called the Prato della Mostra, was created by architect Giovan Battista Bertani, who in 1556 unified the surrounding buildings in the mannerist style of Giulio Romano, which characterizes the pre-existing La Rustica palace overlooking it. It was the place where the Gonzaga horses ready for sale were displayed, considered by the Gonzaga, along with dogs and falcons, the most loyal animals to humans. The courtyard features a rusticated base typical of Giulio Romano and an upper order of Solomonic columns.

- The Garden of the Simples, also called the Garden of the Pavilion, retains its original plant layout. Established in the 15th century concurrently with the Domus Nova, it was reorganized in 1603 by the Florentine friar Zenobio Bocchi,[35] who planted medicinal herbs, known as "simples." This garden was particularly important for the hygiene of the lordship’s members, who reportedly did not bathe in winter but perfumed their clothes with the garden’s flowers and rare essences.

- The Hanging Garden in the refectory, a late 16th-century construction by the Mantuan architect Pompeo Pedemonte at the request of Duke Guglielmo Gonzaga, is situated 12 meters above ground. In the 18th century, under Austrian rule, a Caffehaus was built there, designed by Antonio Galli da Bibbiena.

- The Secret Garden, an integral part of Isabella d’Este’s Grotta Apartment in Corte Vecchia, was completed in 1522 by the Mantuan architect Gian Battista Covo.

- The Courtyard of Santa Croce features a column dedicated to Saint Longinus, the Roman centurion who pierced Jesus’ side on the cross. The column was originally placed during the Council of Mantua (1459–60) in the Cappadocia district at the presumed site of Longinus’ martyrdom near the Church of Santa Maria del Gradaro. When the Gradaro area was transformed into an industrial zone in the second half of the 19th century, the column was moved first to the courtyard of the Palazzo dell’Accademia and then, on April 6, 1915, to the Courtyard of Santa Croce in Palazzo Ducale. The column, 4 meters tall, consists of a porphyry base (a Roman-era erratic), a red Verona marble column, and an iron cross.[36]

- Courtyard of the Eight Faces, also called the Courtyard of the Bears.

- Courtyard of the Frambus.

- Courtyard of Honor, also called the Ducal Garden.

- Courtyard of Santa Croce.

- Courtyard of the Dogs.

Surveyors of the Gonzaga Works

The directors of the construction and decoration works of the Gonzaga palace (appointed from 1450) were:[37]

- Luca Fancelli 1450–1490

- Bernardino Ghisolfo 1490–1511

- Battista da Covo 1513–1524

- Giulio Romano 1524–1546

- Giovan Battista Bertani 1549–1576

- Giovanni Battista Zelotti 1576–1578

- Pompeo Pedemonte 1579–1580

- Bernardino Brugnoli 1580

- Bernardino Facciotto 1580–1581

- Bernardino Brugnoli 1581–1583

- Oreste Biringucci Vannocci 1583–1585

- Pompeo Pedemonte 1585–1587

- Carlo Lambardi 1588

- Giuseppe Dattaro 1590

- Ippolito Andreasi 1590–1591

- Giuseppe Dattaro 1592–1595

- Antonio Maria Viani 1595–1632

- Nicolò Sebregondi 1637–1652

- Daniel van den Dyck 1658–1661

- Frans Geffels 1662–1671

- Fabrizio Carini Motta 1671–1698

Artworks

Roman Era

- Torso of Aphrodite, 350 BC, statue, Roman copy of a Greek original by Praxiteles, anonymous author

Gothic

- Tomb Effigy of Margherita Malatesta, sculptural work, Pierpaolo dalle Masegne

- Tournament Scene, frescoes and sinopie, Pisanello

Early Renaissance

- Camera degli Sposi, 1464–75, fresco, Andrea Mantegna

- Saint Paul, statue, Andrea Mantegna

- Bust of Faustina Major, sculpture, Andrea Mantegna

- Bust of Marquess Francesco II Gonzaga, ca. 1498, terracotta, Antoniazzo Romano

- Tapestries of the Acts of the Apostles, nine tapestries based on designs by Raphael

- Battle between the Gonzaga and the Bonacolsi, 1494, oil on canvas, Domenico Morone

- Lamentation over the Dead Christ, 1533, Lorenzo Leonbruno

- Madonna with Child and Saints, oil on canvas, attributed to Ippolito Costa[38]

Mannerism

- Vulcan Forging Achilles’ Armor, fresco, Giulio Romano

- The Construction of the Wooden Horse of Troy, fresco, Giulio Romano

- Zodiac Signs, fresco, Lorenzo Costa the Younger

- Adoration of the Shepherds, oil on canvas, Lorenzo Costa the Younger[39]

- Resurrection, oil on canvas, Lorenzo Costa the Younger[39]

- The Martyrdom of Saint John the Evangelist, oil on canvas, Girolamo Mazzola Bedoli

- Meeting at the Golden Gate, oil on canvas, Teodoro Ghisi (two works)[38]

- Fall of Saul, 1560, Girolamo Mazzola Bedoli[38]

- Flagellation of Christ, 1539–40, oil on canvas, 258x183 cm, Rinaldo Mantovano

- Deposition of Christ in the Tomb, 1539–40, oil on canvas, 258x173 cm, Fermo Ghisoni

- Adoration of the Shepherds, ca. 1580–90, oil on panel, 76x53 cm, Sebastiano Filippi known as Bastianino

Baroque

- The Gonzaga Family in Adoration of the Holy Trinity, 1604–05, oil on canvas, 381x477 cm, Peter Paul Rubens

- Martyrdom of Saint Ursula, sketch attributed to Peter Paul Rubens[40]

- Saint Michael the Archangel Defeating the Demon, 1594–95, oil on canvas, 330x233 cm, Antonio Maria Viani

- The Virgin Presenting Saint Margaret to the Trinity, 1619, oil on canvas, 451x374 cm, Antonio Maria Viani[40]

- Immaculate Madonna, 1620–1623, Antonio Maria Viani[38]

- Madonna with Child and Saints, 1614, Jacopo Borbone[38]

- Annunciation, Lucrina Fetti

- Portrait of Margherita Gonzaga, Lucrina Fetti

- Portrait of Margherita Gonzaga, Full Figure, Lucrina Fetti

- Portrait of Empress Eleonora Gonzaga, 1622, oil on canvas, Lucrina Fetti

- Portrait of Caterina de’ Medici Gonzaga, 1626, Lucrina Fetti

- Portrait of Eleonora II, 1651, Lucrina Fetti

- Multiplication of the Loaves and Fishes, 1616–18, oil on canvas, 356x853 cm, Domenico Fetti

- Presentation of the Virgin at the Temple, 1615–16, oil on canvas, 215x148 cm, Domenico Fetti

- Margherita Gonzaga Receives the Model of the Church of Saint Ursula from Architect Antonio Maria Viani, oil on canvas, 250x274 cm, Domenico Fetti

- Eleven Apostles and the Blessing Christ, 1616–18, series of 12 paintings, oil on canvas, 215x148 cm, Domenico Fetti

- Holy Martyrs, series of 6 paintings, oil on slate, 70x54 cm, Domenico Fetti

- Portrait of Laura d’Este, oil on canvas, 218x132 cm, Sante Peranda

- Portrait of Alessandro I Pico, oil on canvas, 156x130 cm, Sante Peranda

- Portrait of Alessandro I Pico, oil on canvas, 223x132.3 cm, Sante Peranda

- Psyche Carried to the Edge of the Abyss, oil on canvas, 157.8x224.4 cm, Sante Peranda

- Psyche Cutting a Lock of Wool, oil on canvas, 117.7x177.2 cm, Sante Peranda

- Portrait of Giovan Francesco II Pico, oil on canvas, 128.7x111.3 cm, Sante Peranda

- Hall of Rivers, 1773, frescoes, Giorgio Anselmi

- Saint Francis Praying to the Madonna for the End of an Epidemic, 1605, oil on canvas, 322x197 cm, Francesco Borgani[38]

- Madonna with Saint Isidore the Farmer and Job, pupils of Francesco Borgani[40]

- Saint Clare Expelling the Saracens, 1614–16, oil on canvas, 436x365 cm, Carlo Bononi[38]

- Annunciation, Karl Santner[38]

- Christ in Glory Among the Saints, Pietro Martire Neri[38]

- Communion of Saint Jerome, Domenico Maria Canuti[38]

- Saint Francis Regis, Giuseppe Maria Crespi[38]

- Saint Francis de Sales, Giuseppe Maria Crespi[38]

- Immaculate Madonna, Giuseppe Orioli[38]

- Blessed Osanna Andreasi, Giuseppe Orioli[41]

- Saint Longinus, Giuseppe Orioli[41]

- The Virgin Between Saint John of Capistrano and Saint John the Good, Giuseppe Bazzani[41]

- Vision of Saint Thomas, Giuseppe Bazzani[41]

- Holy Family with Saint Roch, Giuseppe Bazzani[39]

- Death of Saint Joseph,[42] 1755–60, oil on canvas, 110x164 cm, Giuseppe Bazzani

- Neptune on Seahorses, Francesco Maria Raineri[43]

- Saint Joseph Appears to Saint Teresa and Saint Peter of Alcantara, with Blessed Chiara Maria della Passione and an Angel, ca. 1750, Francesco Maria Raineri[41]

- Madonna with Child Surrounded by Six Capuchin Saints, Siro Baroni[43]

- The Marriage of the Virgin, Daniel van den Dyck[40]

- The Iron Age, Palma il Giovane[44]

- Princesses of Mirandola, two marble busts, 1689, Lorenzo Ottoni[44]

- Putti Playing with Dogs, 1580, Lorenzo Costa the Younger[44]

- Bianca Maria Petrozzani with Her Children, 1595–1600, Pietro Facchetti[44]

Gonzaga Collection

"GONZAGA. THE CELESTIAL GALLERY. The Museum of the Dukes of Mantua," curated and conceived by Andrea Emiliani and Raffaella Morselli, was an exhibition held from September 2, 2002, to January 12, 2003, in Mantua at the Palazzo del Te and Palazzo Ducale, to showcase after four centuries a precious selection of the Gonzaga collection, which at its peak included two thousand paintings by the era’s greatest artists and around twenty thousand precious objects displayed in Palazzo Ducale.

Image gallery

-

Palazzo del Capitano

-

Corte Nuova and Castello di San Giorgio. Photo by Paolo Monti

-

Castello di San Giorgio

-

Castel San Giorgio at night

-

Piazza Castello

-

Bell tower of the Palatine Basilica of Santa Barbara

-

Hanging Garden

-

Frescoed room

-

Studiolo of Isabella d’Este (detail)

-

Detail of the Studiolo of Isabella d’Este

-

Studiolo of Isabella d’Este

-

Camera degli Sposi

-

Camera degli Sposi

-

Camera degli Sposi

-

Camera degli Sposi

-

Camera degli Sposi

-

Camera degli Sposi, Ludovico Gonzaga and the secretary Marsilio Andreasi

See also

- House of Gonzaga

- Andrea Mantegna

- Giulio Romano

- Giovan Battista Bertani

- Luca Fancelli

- Pisanello

- Basilica palatina di Santa Barbara

- War of the Mantuan Succession

References

- ^ a b Amadei & Marani (1975, p. 119).

- ^ a b "Dati visitatori dei siti museali italiani statali nel 2019" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved October 7, 2021..

- ^ Amadei & Marani (1975, p. 120).

- ^ Palazzo Ducale Mantova.

- ^ Comune di Mantova. Palazzo Ducale.

- ^ Angela, Alberto (March 12, 2019). St 2019 Puntata del 12/03/2019. Meraviglie - La penisola dei tesori. Rai 1. Event occurs at 00:18:40. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ Paccagnini (2002, p. 24).

- ^ a b L'Occaso (2011, p. 30)

- ^ L'Occaso (2011, p. 35)

- ^ Scansani, Stefano (May 22, 2012). "Ferito anche Palazzo Ducale che resta ancora chiuso". Gazzetta di Mantova. Archived from the original on June 1, 2012. Retrieved June 1, 2012.

- ^ Scansani, Stefano (June 1, 2012). "Allarme per una lesione nella Camera Picta di Mantegna". Gazzetta di Mantova. Archived from the original on June 2, 2012. Retrieved June 3, 2012.

- ^ Scavazza, Graziella (April 3, 2015). "Mantova, in 1.400 al Ducale per l'apertura della Camera degli Sposi". gazzettadimantova.gelocal.it. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- ^ "Visitatori e attività del Museo di Palazzo Ducale nel 2011". Archived from the original on April 16, 2014. Retrieved April 8, 2013.

- ^ "Visitatori e attività del Museo di Palazzo Ducale nel 2012". Archived from the original on August 4, 2016. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ^ "Palazzo Ducale da record: In sei mesi sfiorati i 200mila visitatori".

- ^ Editorial Staff (July 5, 2024). "Palazzo Ducale, numeri in continua crescita: oltre 287mila visitatori nel 2023". la Voce Di Mantova (in Italian). Archived from the original on July 5, 2024. Retrieved February 5, 2025.

- ^ Rebecchini, Guido (2008). Il Rinascimento a Mantova. Giunti. ISBN 978-88-09-06179-8. OCLC 276427547.

- ^ a b del Piano, Cristina (November 17, 2021). "Pisanello 2022: riallestimento della sala e una grande mostra da ottobre a gennaio". Gazzetta di Mantova. p. 39.

- ^ "Magna Domus e Palazzo del Capitano". 1996. Archived from the original on September 21, 2016. Retrieved December 7, 2018.

- ^ Astrology, Magic, Alchemy, Dictionaries of Art, ed. Electa, 2004, p. 27.

- ^ TCI (1970, p. 538).

- ^ La scultura funebre per Alda d’Este.

- ^ TCI (1970, p. 539).

- ^ L'Occaso (2011, p. 3).

- ^ a b c d e f TCI (1970, p. 544).

- ^ "Stanza di Giuditta". lombardiabeniculturali.it. Archived from the original on October 12, 2022. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ a b Paccagnini (2002, p. 46).

- ^ "Ultimi giorni per l'ippopotamo". Palazzo Ducale Mantova (in Italian). Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved February 4, 2023.

- ^ Paccagnini (2002, p. 44).

- ^ Del Piano, Cristina (January 24, 2019). "Giulio Romano 2019: il Ducale si prepara. Al via i restauri nella Galleria della Mostra". Gazzetta di Mantova. pp. 32–33.

- ^ Paccagnini (2002, p. 48).

- ^ Paccagnini (2002, p. 47)

- ^ Paccagnini (2002, p. 52).

- ^ Il cimitero ducale

- ^ "Gazzetta di Mantova. Erbe, alchimia e ottocento visitatori". Archived from the original on November 3, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ^ Committee of the Mantova Carolingia Association (May 17, 2020). "Se riportassimo al Gradaro il monumento di Longino? (è chiuso in Palazzo Ducale)". Gazzetta di Mantova. p. 40.

- ^ Amadei & Marani (1975, p. 293).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m L'Occaso (2011, p. 32).

- ^ a b c "PRESENTAZIONE NUOVE ACQUISIZIONI delle COLLEZIONI del MUSEO di PALAZZO DUCALE". Archived from the original on November 18, 2014. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ^ a b c d L'Occaso (2011, p. 41).

- ^ a b c d e L'Occaso (2011, p. 35).

- ^ "Scheda su museiditalia". Archived from the original on February 25, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- ^ a b "Dipinti dello Schivenoglia e di Siro Baroni restaurati a cura della Società". societapalazzoducalemantova.com. 18 December 2020. Archived from the original on November 1, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c d L'Occaso (2011, p. 52).

Bibliography

- Amadei, Giuseppe; Marani, Ercolano, eds. (1975). I Gonzaga a Mantova [The Gonzagas in Mantua]. Milan.

- Algeri, Giuliana (2003). Il Palazzo Ducale di Mantova [The Ducal Palace in Mantua]. Mantua.

- L'Occaso, Stefano (2002). Il Palazzo Ducale di Mantova [The Ducal Palace in Mantua]. Milan.

- TCI (1970). Lombardia. Guide d'Italia [Lombardy. Guides to Italy]. Milan: Touring Club Italiano.

- Paccagnini, Giovanni (2002). Il Palazzo Ducale di Mantova [The Ducal Palace in Mantua]. Milan.

- Berzaghi, Renato (1992). Il Palazzo Ducale di Mantova [The Ducal Palace in Mantua]. Milan.

- L'Occaso, Stefano (2011). Museo di Palazzo Ducale di Mantova - Catalogo generale delle collezioni inventariate - Dipinti fino al XIX secolo [Ducal Palace Museum of Mantua - General catalog of inventoried collections - Paintings up to the 19th century]. Mantua: Publi Paolini Editore.