Translation (biology)

| Part of a series on |

| Biology |

|---|

|

Translation is the process in biological cells in which proteins are produced using RNA molecules as templates. The generated protein is a sequence of amino acids determined by the sequence of nucleotides in the RNA. The nucleotides are considered three at a time. Each such triple results in the addition of one specific amino acid to the protein being generated. The matching from nucleotide triple to amino acid is called the genetic code. The translation is performed by a large complex of functional RNA and proteins called ribosomes. The entire process is called gene expression.

In translation, messenger RNA (mRNA) is decoded in a ribosome, outside the nucleus, to produce a specific amino acid chain, or polypeptide. The polypeptide later folds into an active protein and performs its functions in the cell. The polypeptide can also start folding during protein synthesis.[1] The ribosome facilitates decoding by inducing the binding of complementary transfer RNA (tRNA) anticodon sequences to mRNA codons. The tRNAs carry specific amino acids that are chained together into a polypeptide as the mRNA passes through and is "read" by the ribosome. The three stages of translation are initiation, elongation, and termination.

Basic mechanisms

The basic process of protein production is the addition of one amino acid at a time to the end of a forming polypeptide chain. This operation is performed by a ribosome.[2] A ribosome is made up of two subunits, in the eukaryote a small (40S) subunit, and a large (60S) subunit. These subunits come together before the translation of mRNA into a protein to provide a location for translation to be carried out and a polypeptide to be produced.[3] The choice of amino acid type to add is determined by a messenger RNA (mRNA) molecule. Each amino acid added is matched to a three-nucleotide subsequence of the mRNA. For each such triplet possible, the corresponding amino acid is accepted. The successive amino acids added to the chain are matched to successive nucleotide triplets in the mRNA. In this way, the sequence of nucleotides in the template mRNA chain determines the sequence of amino acids in the generated amino acid chain.[4] The addition of an amino acid occurs at the C-terminus of the peptide; thus, translation is said to be amine-to-carboxyl directed.[5]

The mRNA carries genetic information encoded as a ribonucleotide sequence from the chromosomes to the ribosomes. The ribonucleotides are "read" by translational machinery in a sequence of nucleotide triplets called codons. Each of those triplets codes for a specific amino acid.[citation needed]

The ribosome molecules translate this code to a specific sequence of amino acids. The ribosome is a multisubunit structure containing ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and proteins. It is the "factory" where amino acids are assembled into proteins.

Transfer RNAs (tRNAs) are small noncoding RNA chains (74–93 nucleotides) that transport amino acids to the ribosome. The repertoire of tRNA genes varies widely between species, with some bacteria having between 20 and 30 genes while complex eukaryotes could have thousands.[6] tRNAs have a site for amino acid attachment, and a site called an anticodon. The anticodon is an RNA triplet complementary to the mRNA triplet that codes for their cargo amino acid.

Aminoacyl tRNA synthetases (enzymes) catalyze the bonding between specific tRNAs and the amino acids that their anticodon sequences call for. The product of this reaction is an aminoacyl-tRNA. The amino acid is joined by its carboxyl group to the 3' OH of the tRNA by an ester bond. When the tRNA has an amino acid linked to it, the tRNA is termed "charged". Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases that mispair tRNAs with the wrong amino acids can produce mischarged aminoacyl-tRNAs, which can result in inappropriate amino acids at the respective position in the protein. This "mistranslation"[7] of the genetic code naturally occurs at low levels in most organisms, but certain cellular environments cause an increase in permissive mRNA decoding, sometimes to the benefit of the cell.

The ribosome has two binding sites for tRNA. They are the aminoacyl site (abbreviated A), and the peptidyl site/ exit site (abbreviated P/E). Concerning the mRNA, the three sites are oriented 5' to 3' E-P-A, because ribosomes move toward the 3' end of mRNA. The A-site binds the incoming tRNA with the complementary codon on the mRNA. The P/E-site holds the tRNA with the growing polypeptide chain. When an aminoacyl-tRNA initially binds to its corresponding codon on the mRNA, it is in the A site. Then, a peptide bond forms between the amino acid of the tRNA in the A site and the amino acid of the charged tRNA in the P/E site. The growing polypeptide chain is transferred to the tRNA in the A site. Translocation occurs, moving the tRNA to the P/E site, now without an amino acid; the tRNA that was in the A site, now charged with the polypeptide chain, is moved to the P/E site and the uncharged tRNA leaves, and another aminoacyl-tRNA enters the A site to repeat the process.[8]

After the new amino acid is added to the chain, and after the tRNA is released out of the ribosome and into the cytosol, the energy provided by the hydrolysis of a GTP bound to the translocase EEF2 moves the ribosome down one codon towards the 3' end. The energy required for translation of proteins is significant. For a protein containing n amino acids, the number of high-energy phosphate bonds required to translate it is 4n-1.[9] The rate of translation varies; it is significantly higher in prokaryotic cells (up to 17–21 amino acid residues per second) than in eukaryotic cells (up to 6–9 amino acid residues per second).[10]

Stages

Translation proceeds in four phases: initiation, elongation, termination, and recycling.[11]

Initiation

Initiation involves the small subunit of the ribosome binding to the 5' end of mRNA with the help of initiation factors.[12] The ribosome and its associated factors assemble and bind to an mRNA. The first tRNA is attached at the start codon. This process is defined as either cap-dependent, in which the ribosome binds initially at the 5' cap and then travels to the stop codon, or as cap-independent, where the ribosome does not initially bind the 5' cap. The 5' cap is added when the nascent pre-mRNA is about 20 nucleotides long.[13]

Cap-dependent initiation

Initiation of translation usually involves the interaction of certain key proteins, the initiation factors, with a special tag bound to the 5'-end of an mRNA molecule, the 5' cap, as well as with the 5' UTR. These proteins bind the small (40S) ribosomal subunit and hold the mRNA in place.[14]

eIF3 is associated with the 40S ribosomal subunit and plays a role in keeping the large (60S) ribosomal subunit from prematurely binding. eIF3 also interacts with the eIF4F complex, which consists of three other initiation factors: eIF4A, eIF4E, and eIF4G. eIF4G is a scaffolding protein that directly associates with both eIF3 and the other two components. eIF4E is the cap-binding protein. Binding of the cap by eIF4E is often considered the rate-limiting step of cap-dependent initiation, and the concentration of eIF4E is a regulatory nexus of translational control. Certain viruses cleave a portion of eIF4G that binds eIF4E, thus preventing cap-dependent translation to hijack the host machinery in favor of the viral (cap-independent) messages. eIF4A is an ATP-dependent RNA helicase that aids the ribosome by resolving certain secondary structures formed along the mRNA transcript. Recent structural biology results also indicated that a second eIF4A protein can simultaneously associate with the initiation complex, specifically interacting with eIF3.[15][16] The poly(A)-binding protein (PABP) also associates with the eIF4F complex via eIF4G, and binds the poly-A tail of most eukaryotic mRNA molecules. This protein has been implicated in playing a role in circularization of the mRNA during translation.[17]

This 43S preinitiation complex (43S PIC) accompanied by the protein factors moves along the mRNA chain toward its 3'-end, in a process known as 'scanning', to reach the start codon (typically AUG). In eukaryotes and archaea, the amino acid encoded by the start codon is methionine. The Met-charged initiator tRNA (Met-tRNAiMet) is brought to the P-site of the small ribosomal subunit by eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2). It hydrolyzes GTP, and signals for the dissociation of several factors from the small ribosomal subunit, eventually leading to the association of the large subunit (or the 60S subunit). The complete ribosome (80S) then commences translation elongation.

Regulation of protein synthesis is partly influenced by phosphorylation of eIF2 (via the α subunit), which is a part of the eIF2-GTP-Met-tRNAiMet ternary complex (eIF2-TC). When large numbers of eIF2 are phosphorylated, protein synthesis is inhibited. This occurs under amino acid starvation or after viral infection. However, a small fraction of this initiation factor is naturally phosphorylated. Another regulator is 4EBP, which binds to the initiation factor eIF4E and inhibits its interactions with eIF4G, thus preventing cap-dependent initiation. To oppose the effects of 4EBP, growth factors phosphorylate 4EBP, reducing its affinity for eIF4E and permitting protein synthesis.[citation needed]

While protein synthesis is globally regulated by modulating the expression of key initiation factors as well as the number of ribosomes, individual mRNAs can have different translation rates due to the presence of regulatory sequence elements. This has been shown to be important in a variety of settings including yeast meiosis and ethylene response in plants. In addition, recent work in yeast and humans suggest that evolutionary divergence in cis-regulatory sequences can impact translation regulation.[18] Additionally, RNA helicases such as DHX29 and Ded1/DDX3 participate in the process of translation initiation, especially for mRNAs with structured 5'UTRs.[19][20]

Cap-independent initiation

The best-studied example of cap-independent translation initiation in eukaryotes uses the internal ribosome entry site (IRES). Unlike cap-dependent translation, cap-independent translation does not require a 5' cap to initiate scanning from the 5' end of the mRNA until the start codon. The ribosome can localize to the start site by direct binding, initiation factors, and/or ITAFs (IRES trans-acting factors) bypassing the need to scan the entire 5' UTR. This method of translation is important in conditions that require the translation of specific mRNAs during cellular stress, when overall translation is reduced. Examples include factors responding to apoptosis and stress-induced responses.[21]

Elongation

Elongation depends on elongation factors. At the end of the initiation step, the mRNA is positioned so that the next codon can be translated during the elongation stage of protein synthesis. The initiator tRNA occupies the P site in the ribosome, and the A site is ready to receive an aminoacyl-tRNA. During chain elongation, each additional amino acid is added to the nascent polypeptide chain in a three-step microcycle. The steps in this microcycle are (1) positioning the correct aminoacyl-tRNA in the A site of the ribosome, which is brought into that site by eEF1, (2) forming the peptide bond, and (3) shifting the mRNA by one codon relative to the ribosome with the help of eEF2. Unlike bacteria, in which translation initiation occurs as soon as the 5' end of an mRNA is synthesized, in eukaryotes, such tight coupling between transcription and translation is not possible because transcription and translation are carried out in separate compartments of the cell (the nucleus and cytoplasm). Eukaryotic mRNA precursors must be processed in the nucleus (e.g., capping, polyadenylation, splicing) in ribosomes before they are exported to the cytoplasm for translation. Translation can also be affected by ribosomal pausing, which can trigger endonucleolytic attack of the tRNA, a process termed mRNA no-go decay. Ribosomal pausing also aids co-translational folding of the nascent polypeptide on the ribosome, and delays protein translation while it is encoding tRNA. This can trigger ribosomal frameshifting.[22]

The last tRNA validated by the small ribosomal subunit (accommodation) transfers the amino acid. It carries to the large ribosomal subunit which binds it to one of the preceding admitted tRNA (transpeptidation). The ribosome then moves to the next mRNA codon to continue the process (translocation), creating an amino acid chain.

In bacterial translation, and archaeal translation, translation occurs in the cytosol, where the ribosome binds to the mRNA. In eukaryotes, translation can occur in the cytoplasm and also across the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum through a process called co-translational translocation. In co-translational translocation, the entire ribosome–mRNA complex binds to the outer membrane of the rough endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and the new protein is synthesized and released into the ER; the newly created polypeptide can be immediately secreted or stored inside the ER for future vesicle transport and secretion outside the cell.

Many types of transcribed RNA, such as tRNA, ribosomal RNA, and small nuclear RNA, do not undergo a translation into proteins.

Several antibiotics act by inhibiting translation. These include anisomycin, cycloheximide, chloramphenicol, tetracycline, streptomycin, erythromycin, and puromycin. Prokaryotic ribosomes have a different structure from that of eukaryotic ribosomes, and thus antibiotics can specifically target bacterial infections without harming a eukaryotic host's cells.

Termination

Termination of elongation depends on the release factor eRF1 that recognizes all three stop codons. When a stop codon is reached, termination of the polypeptide occurs the ribosome is disassembled and the completed polypeptide is released. eRF3 is a ribosome-dependent GTPase that helps eRF1 release the completed polypeptide. The human genome encodes a few genes whose mRNA stop codons are surprisingly leaky: In these genes, termination of translation is inefficient due to special RNA bases in the vicinity of the stop codon. Leaky termination in these genes leads to translational readthrough of up to 10% of the stop codons of these genes. Some of these genes encode functional protein domains in their readthrough extension so that new protein isoforms can arise. This process has been termed 'functional translational readthrough'.[23]

When the A site of the ribosome is occupied by a stop codon (UAA, UAG, or UGA) on the mRNA, creating the primary structure of a protein. tRNA usually cannot recognize or bind to stop codons. Instead, the stop codon induces the binding of a release factor protein[24] (RF1 & RF2) that prompts the disassembly of the entire ribosome/mRNA complex by the hydrolysis of the polypeptide chain from the peptidyl transferase center [2] of the ribosome.[25] Drugs or special sequence motifs on the mRNA can change the ribosomal structure so that near-cognate tRNAs are bound to the stop codon instead of the release factors. In such cases of 'translational readthrough', translation continues until the ribosome encounters the next stop codon.[23]

Recycling

When the synthesised protein is released the complex ribosome disassembles into its subunits for recycling.[11]

Errors in translation

Even though the ribosomes are usually considered accurate and processive machines, the translation process is subject to errors that can lead either to the synthesis of erroneous proteins or to the premature abandonment of translation, either because a tRNA couples to a wrong codon or because a tRNA is coupled to the wrong amino acid.[26] The rate of error in synthesizing proteins has been estimated to be between 1 in 105 and 1 in 103 misincorporated amino acids, depending on the experimental conditions.[27] The rate of premature translation abandonment, instead, has been estimated to be of the order of magnitude of 10−4 events per translated codon.[28][29]

Regulation

Translation is one of the key energy consumers in cells, hence it is strictly regulated. Numerous mechanisms have evolved that control and regulate translation in eukaryotes as well as prokaryotes. Regulation of translation can impact the global rate of protein synthesis which is closely coupled to the metabolic and proliferative state of a cell.

To study this process, scientists have used a wide variety of methods such as structural biology, analytical chemistry (mass-spectrometry based), imaging of reporter mRNA translation (in which the translation of a mRNA is linked to an output, such as luminescence or fluorescence), and next-generation sequencing based methods.[30] Other methods such as toeprinting assay can also be used to determine the location of ribosomes of a particular mRNA in vitro, and footprints of other proteins regulating translation. To delve deeper into this intricate process, scientists typically use a technique known as ribosome profiling.[31] This method enables researchers to take a snapshot of the translatome, showing which parts of the mRNA are being translated into proteins by ribosomes at a given time. Ribosome profiling provides valuable insights into translation dynamics, revealing the complex interplay between gene sequence, mRNA structure, and translation regulation.[18] Expanding on this concept, single-cell ribosome profiling, is a technique that allows the study of the translation process at the resolution of individual cells.[32] Single-cell ribosome profiling has revealed that genetic differences and their subsequent expression as mRNAs can also impact translation rate in an RNA-specific manner. Single-cell ribosome profiling has the potential to shed light on the heterogeneous nature of cells, leading to a more nuanced understanding of how translation regulation can impact cell behavior, metabolic state, and responsiveness to various stimuli or conditions.

Amino acid substitution

In some cells certain amino acids can be depleted and thus affect translation efficiency. For instance, activated T cells secrete interferon-γ which triggers intracellular tryptophan shortage by upregulating the indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) enzyme. Despite tryptophan depletion, in-frame protein synthesis continues across tryptophan codons. This is achieved by incorporation of phenylalanine instead of tryptophan. The resulting peptides are called W>F "substitutants". Such W>F substitutants are abundant in certain cancer types and have been associated with increased IDO1 expression. Functionally, W>F substitutants can impair protein activity.[33]

Clinical significance

Translational control is critical for the development and survival of cancer. Cancer cells must frequently regulate the translation phase of gene expression, though it is not fully understood why translation is targeted over steps like transcription. While cancer cells often have genetically altered translation factors, it is much more common for cancer cells to modify the levels of existing translation factors.[34] Several major oncogenic signaling pathways, including the RAS–MAPK, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, MYC, and WNT–β-catenin pathways, ultimately reprogram the genome via translation.[35] Cancer cells also control translation to adapt to cellular stress. During stress, the cell translates mRNAs that can mitigate the stress and promote survival. An example of this is the expression of AMPK in various cancers; its activation triggers a cascade that can ultimately allow the cancer to escape apoptosis (programmed cell death) triggered by nutrition deprivation. Future cancer therapies may involve disrupting the translation machinery of the cell to counter the downstream effects of cancer.[34]

Mathematical modeling of translation

The transcription-translation process description, mentioning only the most basic "elementary" processes, consists of:

- production of mRNA molecules (including splicing),

- initiation of these molecules with help of initiation factors (e.g., the initiation can include the circularization step though it is not universally required),

- initiation of translation, recruiting the small ribosomal subunit,

- assembly of full ribosomes,

- elongation, (i.e. movement of ribosomes along mRNA with production of protein),

- termination of translation,

- degradation of mRNA molecules,

- degradation of proteins.

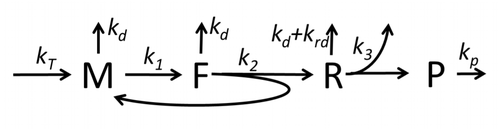

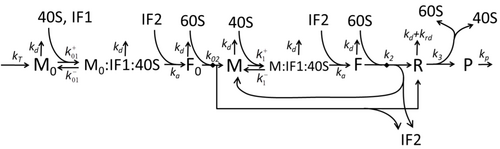

The process of amino acid building to create protein in translation is a subject of various physic models for a long time starting from the first detailed kinetic models such as[37] or others taking into account stochastic aspects of translation and using computer simulations. Many chemical kinetics-based models of protein synthesis have been developed and analyzed in the last four decades.[38][39] Beyond chemical kinetics, various modeling formalisms such as Totally Asymmetric Simple Exclusion Process,[39] Probabilistic Boolean Networks, Petri Nets and max-plus algebra have been applied to model the detailed kinetics of protein synthesis or some of its stages. A basic model of protein synthesis that takes into account all eight 'elementary' processes has been developed,[36] following the paradigm that "useful models are simple and extendable".[40] The simplest model M0 is represented by the reaction kinetic mechanism (Figure M0). It was generalised to include 40S, 60S and initiation factors (IF) binding (Figure M1'). It was extended further to include effect of microRNA on protein synthesis.[41] Most of models in this hierarchy can be solved analytically. These solutions were used to extract 'kinetic signatures' of different specific mechanisms of synthesis regulation.

Genetic code

It is also possible to translate either by hand (for short sequences) or by computer (after first programming one appropriately, see section below); this allows biologists and chemists to draw out the primary amino acid sequence of the encoded protein on paper.

First, convert each template DNA base to its RNA complement (note that the complement of A is now U), as shown below. Note that the template strand of the DNA is the one the RNA is polymerized against; the other DNA strand would be the same as the RNA, but with thymine instead of uracil.

DNA -> RNA A -> U T -> A C -> G G -> C A=T-> A=U

Then split the RNA into triplets (groups of three bases). Note that there are 3 translation "windows", or reading frames, depending on where you start reading the code. Finally, use the table at Genetic code to translate the above into a structural formula as used in chemistry.

This will give the primary structure of the protein. However, proteins tend to fold, depending in part on hydrophilic and hydrophobic segments along the chain. Secondary structure can often still be guessed, but the proper tertiary structure is often very hard to determine. In order to determine the precise 3D structure and atomic interactions, Structural biology and several other Biophysics methods are used.

Whereas other aspects such as the 3D structure, called tertiary structure, of protein can only be predicted using sophisticated algorithms, the amino acid sequence, called primary structure, can be determined solely from the nucleic acid sequence with the aid of a translation table.

This approach may not give the correct amino acid composition of the protein, in particular if unconventional amino acids such as selenocysteine are incorporated into the protein, which is coded for by a conventional stop codon in combination with a downstream hairpin (SElenoCysteine Insertion Sequence, or SECIS).

There are many computer programs capable of translating a DNA/RNA sequence into a protein sequence. Normally this is performed using the Standard Genetic Code, however, few programs can handle all the "special" cases, such as the use of the alternative initiation codons which are biologically significant. For instance, the rare alternative start codon CTG codes for Methionine when used as a start codon, and for Leucine in all other positions.

Example: Condensed translation table for the Standard Genetic Code (from the NCBI Taxonomy webpage).[42]

AAs = FFLLSSSSYY**CC*WLLLLPPPPHHQQRRRRIIIMTTTTNNKKSSRRVVVVAAAADDEEGGGG Starts = ---M---------------M---------------M---------------------------- Base1 = TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG Base2 = TTTTCCCCAAAAGGGGTTTTCCCCAAAAGGGGTTTTCCCCAAAAGGGGTTTTCCCCAAAAGGGG Base3 = TCAGTCAGTCAGTCAGTCAGTCAGTCAGTCAGTCAGTCAGTCAGTCAGTCAGTCAGTCAGTCAG

The "Starts" row indicate three start codons, UUG, CUG, and the very common AUG. It also indicates the first amino acid residue when interpreted as a start: in this case it is all methionine.

Translation tables

Even when working with ordinary eukaryotic sequences such as the Yeast genome, it is often desired to be able to use alternative translation tables—namely for translation of the mitochondrial genes. Currently the following translation tables are defined by the NCBI Taxonomy Group for the translation of the sequences in GenBank:[42]

- The standard code

- The vertebrate mitochondrial code

- The yeast mitochondrial code

- The mold, protozoan, and coelenterate mitochondrial code and the mycoplasma/spiroplasma code

- The invertebrate mitochondrial code

- The ciliate, dasycladacean and hexamita nuclear code

- The kinetoplast code

- The echinoderm and flatworm mitochondrial code

- The euplotid nuclear code

- The bacterial, archaeal and plant plastid code

- The alternative yeast nuclear code

- The ascidian mitochondrial code

- The alternative flatworm mitochondrial code

- The Blepharisma nuclear code

- The chlorophycean mitochondrial code

- The trematode mitochondrial code

- The Scenedesmus obliquus mitochondrial code

- The Thraustochytrium mitochondrial code

- The Pterobranchia mitochondrial code

- The candidate division SR1 and gracilibacteria code

- The Pachysolen tannophilus nuclear code

- The karyorelict nuclear code

- The Condylostoma nuclear code

- The Mesodinium nuclear code

- The peritrich nuclear code

- The Blastocrithidia nuclear code

- The Cephalodiscidae mitochondrial code

See also

References

- ^ Liutkute, Marija; Maiti, Manisankar; Samatova, Ekaterina; Enderlein, Jörg; Rodnina, Marina V (2020-10-27). Hegde, Ramanujan S; Wolberger, Cynthia (eds.). "Gradual compaction of the nascent peptide during cotranslational folding on the ribosome". eLife. 9 e60895. doi:10.7554/eLife.60895. ISSN 2050-084X. PMC 7593090. PMID 33112737.

- ^ a b Tirumalai MR, Rivas M, Tran Q, Fox GE (November 2021). "The Peptidyl Transferase Center: a Window to the Past". Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 85 (4) e00104-21: e0010421. Bibcode:2021MMBR...85...21T. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00104-21. PMC 8579967. PMID 34756086.

- ^ Brooker RJ, Widmaier EP, Graham LE, Stiling PD (2014). Biology (Third international student ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill Education. p. 249. ISBN 978-981-4581-85-1.

- ^ Neill C (1996). Biology (Fourth ed.). The Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company. pp. 309–310. ISBN 0-8053-1940-9.

- ^ Stryer L (2002). Biochemistry (Fifth ed.). W. H. Freeman and Company. p. 826. ISBN 0-7167-4684-0.

- ^ Santos, Fenícia Brito; Del-Bem, Luiz-Eduardo (2023). "The Evolution of tRNA Copy Number and Repertoire in Cellular Life". Genes. 14 (1): 27. doi:10.3390/genes14010027. ISSN 2073-4425. PMC 9858662. PMID 36672768.

- ^ Moghal A, Mohler K, Ibba M (November 2014). "Mistranslation of the genetic code". FEBS Letters. 588 (23): 4305–10. Bibcode:2014FEBSL.588.4305M. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2014.08.035. PMC 4254111. PMID 25220850.

- ^ Griffiths A (2008). "9". Introduction to Genetic Analysis (9th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. pp. 335–339. ISBN 978-0-7167-6887-6.

- ^ "Computational Analysis of Genomic Sequences utilizing Machine Learning". scholar.googleusercontent.com. Retrieved 2022-01-12.

- ^ Ross JF, Orlowski M (February 1982). "Growth-rate-dependent adjustment of ribosome function in chemostat-grown cells of the fungus Mucor racemosus". Journal of Bacteriology. 149 (2): 650–3. doi:10.1128/JB.149.2.650-653.1982. PMC 216554. PMID 6799491.

- ^ a b Prabhakar, A; Choi, J; Wang, J; Petrov, A; Puglisi, JD (July 2017). "Dynamic basis of fidelity and speed in translation: Coordinated multistep mechanisms of elongation and termination". Protein science : a publication of the Protein Society. 26 (7): 1352–1362. doi:10.1002/pro.3190. PMID 28480640.

- ^ Nakamoto T (February 2011). "Mechanisms of the initiation of protein synthesis: in reading frame binding of ribosomes to mRNA". Molecular Biology Reports. 38 (2): 847–55. doi:10.1007/s11033-010-0176-1. PMID 20467902. S2CID 22038744.

- ^ Jurado, Ashley R.; Tan, Dazhi; Jiao, Xinfu; Kiledjian, Megerditch; Tong, Liang (2014-04-01). "Structure and function of pre-mRNA 5'-end capping quality control and 3'-end processing". Biochemistry. 53 (12): 1882–1898. doi:10.1021/bi401715v. ISSN 1520-4995. PMC 3977584. PMID 24617759.

- ^ Malys N, McCarthy JE (March 2011). "Translation initiation: variations in the mechanism can be anticipated". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 68 (6): 991–1003. doi:10.1007/s00018-010-0588-z. PMC 11115079. PMID 21076851. S2CID 31720000.

- ^ Brito Querido, Jailson; Sokabe, Masaaki; Díaz-López, Irene; Gordiyenko, Yuliya; Fraser, Christopher S.; Ramakrishnan, V. (2024). "The structure of a human translation initiation complex reveals two independent roles for the helicase eIF4A". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 31 (3): 455–464. doi:10.1038/s41594-023-01196-0. PMC 10948362. PMID 38287194.

- ^ Hellen CU, Sarnow P (July 2001). "Internal ribosome entry sites in eukaryotic mRNA molecules". Genes & Development. 15 (13): 1593–612. doi:10.1101/gad.891101. PMID 11445534.

- ^ Wells SE, Hillner PE, Vale RD, Sachs AB (July 1998). "Circularization of mRNA by eukaryotic translation initiation factors". Molecular Cell. 2 (1): 135–40. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80122-7. PMID 9702200.

- ^ a b Cenik C, Cenik ES, Byeon GW, Grubert F, Candille SI, Spacek D, Alsallakh B, Tilgner H, Araya CL, Tang H, Ricci E, Snyder MP (November 2015). "Integrative analysis of RNA, translation, and protein levels reveals distinct regulatory variation across humans". Genome Research. 25 (11): 1610–21. doi:10.1101/gr.193342.115. PMC 4617958. PMID 26297486.

- ^ Pisareva VP, Pisarev AV, Komar AA, Hellen CU, Pestova TV (December 2008). "Translation initiation on mammalian mRNAs with structured 5'UTRs requires DExH-box protein DHX29". Cell. 135 (7): 1237–50. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.037. PMC 2948571. PMID 19109895.

- ^ Wilkins, Kevin C.; Schroeder, Till; Gu, Sohyun; Revalde, Jezrael L.; Floor, Stephen N. (2024-08-01). "A novel reporter for helicase activity in translation uncovers DDX3X interactions". RNA. 30 (8): 1041–1057. doi:10.1261/rna.079837.123. ISSN 1355-8382. PMID 38697667.

- ^ López-Lastra M, Rivas A, Barría MI (2005). "Protein synthesis in eukaryotes: the growing biological relevance of cap-independent translation initiation". Biological Research. 38 (2–3): 121–46. doi:10.4067/s0716-97602005000200003. hdl:10533/176032. PMID 16238092.

- ^ Buchan JR, Stansfield I (September 2007). "Halting a cellular production line: responses to ribosomal pausing during translation". Biology of the Cell. 99 (9): 475–87. doi:10.1042/BC20070037. PMID 17696878.

- ^ a b Schueren F, Thoms S (August 2016). "Functional Translational Readthrough: A Systems Biology Perspective". PLOS Genetics. 12 (8) e1006196. doi:10.1371/JOURNAL.PGEN.1006196. PMC 4973966. PMID 27490485.

- ^ Baggett NE, Zhang Y, Gross CA (March 2017). Ibba M (ed.). "Global analysis of translation termination in E. coli". PLOS Genetics. 13 (3) e1006676. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006676. PMC 5373646. PMID 28301469.

- ^ Mora L, Zavialov A, Ehrenberg M, Buckingham RH (December 2003). "Stop codon recognition and interactions with peptide release factor RF3 of truncated and chimeric RF1 and RF2 from Escherichia coli". Molecular Microbiology. 50 (5): 1467–76. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03799.x. PMID 14651631.

- ^ Ou X, Cao J, Cheng A, Peppelenbosch MP, Pan Q (March 2019). "Errors in translational decoding: tRNA wobbling or misincorporation?". PLOS Genetics. 15 (3): 2979–2986. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1008017. PMC 3158919. PMID 21930591.

- ^ Wohlgemuth I, Pohl C, Mittelstaet J, Konevega AL, Rodnina MV (October 2011). "Evolutionary optimization of speed and accuracy of decoding on the ribosome". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 366 (1580): 2979–86. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0138. PMC 6438450. PMID 30921315.

- ^ Sin C, Chiarugi D, Valleriani A (April 2016). "Quantitative assessment of ribosome drop-off in E. coli". Nucleic Acids Research. 44 (6): 2528–37. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw137. PMC 4824120. PMID 26935582.

- ^ Awad S, Valleriani A, Chiarugi D (April 2024). "A data-driven estimation of the ribosome drop-off rate in S. cerevisiae reveals a correlation with the genes length". NAR Genomics and Bioinformatics. 6 (2) lqae036. doi:10.1093/nargab/lqae036. PMC 11025885. PMID 38638702.

- ^ Dermit, Maria; Dodel, Martin; Mardakheh, Faraz K. (2017-11-21). "Methods for monitoring and measurement of protein translation in time and space". Molecular BioSystems. 13 (12): 2477–2488. doi:10.1039/C7MB00476A. ISSN 1742-2051. PMC 5795484. PMID 29051942.

- ^ Ingolia NT, Ghaemmaghami S, Newman JR, Weissman JS (April 2009). "Genome-wide analysis in vivo of translation with nucleotide resolution using ribosome profiling". Science. 324 (5924): 218–23. Bibcode:2009Sci...324..218I. doi:10.1126/science.1168978. PMC 2746483. PMID 19213877.

- ^ Ozadam H, Tonn T, Han CM, Segura A, Hoskins I, Rao S; et al. (2023). "Single-cell quantification of ribosome occupancy in early mouse development". Nature. 618 (7967): 1057–1064. Bibcode:2023Natur.618.1057O. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06228-9. PMC 10307641. PMID 37344592.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pataskar, Abhijeet; Champagne, Julien; Nagel, Remco; Kenski, Juliana; Laos, Maarja; Michaux, Justine; Pak, Hui Song; Bleijerveld, Onno B.; Mordente, Kelly; Navarro, Jasmine Montenegro; Blommaert, Naomi (2022-03-24). "Tryptophan depletion results in tryptophan-to-phenylalanine substitutants". Nature. 603 (7902): 721–727. Bibcode:2022Natur.603..721P. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04499-2. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 8942854. PMID 35264796.

- ^ a b Xu Y, Ruggero D (March 2020). "The Role of Translation Control in Tumorigenesis and Its Therapeutic Implications". Annual Review of Cancer Biology. 4 (1): 437–457. doi:10.1146/annurev-cancerbio-030419-033420.

- ^ Truitt ML, Ruggero D (April 2016). "New frontiers in translational control of the cancer genome". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 16 (5): 288–304. doi:10.1038/nrc.2016.27. PMC 5491099. PMID 27112207.

- ^ a b c Gorban AN, Harel-Bellan A, Morozova N, Zinovyev A (July 2019). "Basic, simple and extendable kinetic model of protein synthesis". Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering. 16 (6): 6602–6622. arXiv:1204.5941. doi:10.3934/mbe.2019329. PMID 31698578.

- ^ MacDonald CT, Gibbs JH, Pipkin AC (1968). "Kinetics of biopolymerization on nucleic acid templates". Biopolymers. 6 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1002/bip.1968.360060102. PMID 5641411. S2CID 27559249.

- ^ Heinrich R, Rapoport TA (September 1980). "Mathematical modelling of translation of mRNA in eucaryotes; steady state, time-dependent processes and application to reticulocytes". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 86 (2): 279–313. Bibcode:1980JThBi..86..279H. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(80)90008-9. PMID 7442295.

- ^ a b Skjøndal-Bar N, Morris DR (January 2007). "Dynamic model of the process of protein synthesis in eukaryotic cells". Bulletin of Mathematical Biology. 69 (1): 361–93. doi:10.1007/s11538-006-9128-2. PMID 17031456. S2CID 83701439.

- ^ Coyte KZ, Tabuteau H, Gaffney EA, Foster KR, Durham WM (April 2017). "Reply to Baveye and Darnault: Useful models are simple and extendable". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 114 (14): E2804–E2805. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114E2804C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1702303114. PMC 5389313. PMID 28341710.

- ^ Morozova N, Zinovyev A, Nonne N, Pritchard LL, Gorban AN, Harel-Bellan A (September 2012). "Kinetic signatures of microRNA modes of action". RNA. 18 (9): 1635–55. doi:10.1261/rna.032284.112. PMC 3425779. PMID 22850425.

- ^ a b Elzanowski, Andrzej; Ostell, Jim (January 2019). "The Genetic Codes". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Retrieved 31 May 2022.

Further reading

- Champe PC, Harvey RA, Ferrier DR (2004). Lippincott's Illustrated Reviews: Biochemistry (3rd ed.). Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-2265-9.

- Cox M, Nelson DR, Lehninger AL (2005). Lehninger principles of biochemistry (4th ed.). San Francisco...: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-4339-6.

- Malys N, McCarthy JE (March 2011). "Translation initiation: variations in the mechanism can be anticipated". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 68 (6): 991–1003. doi:10.1007/s00018-010-0588-z. PMC 11115079. PMID 21076851. S2CID 31720000.