Jules Rabin (born April 6, 1924) is an American peace activist, writer, educator, and baker. He is known for his practice of nonviolent resistance during major protest movements spanning more than six decades including protests in favor of reducing and eliminating nuclear weapons, protests in favor of the civil rights movement, and protests in opposition to the Vietnam War. In the late 1960s, he moved from New York City to rural Vermont as part of the back-to-the-land movement. He taught at Goddard College for nine years.

After leaving Goddard, he and his wife Helen started Upland Bakers, an artisan baker of sourdough bread which is credited with contributing to the renaissance of European-style hearth bread in the United States. In subsequent decades, he has been a noticeable presence in the state capitol of Vermont, protesting in opposition to the Iraq War. He has advocated on behalf of the Palestinians for more than two decades, and has actively participated in public protests in opposition to the Gaza war.

Early life and education

Yehuda Moishe Rabinovitz was born on April 6, 1924,[1] and grew up in Roxbury, Boston, Massachusetts,[2] as the youngest of five children.[3] His parents were Lithuanian immigrants.[1] Rabin grew up in poverty in a working class family.[2] His father sorted metal in a junkyard[1] and the family ran a store with the help of their children.[2] His uncle, a Marxist, took him to his first protest—a rally in support of Black labor organizer Angelo Herndon after his conviction for insurrection—when he was eight years old.[1] Rabin recalls that his uncle followed the tradition of the Haskalah, the Jewish Enlightenment, which rejected rabbinic authority.[4]

Rabin attended the Boston Latin School before going on to Harvard. After his first semester, he joined the United States Army.[2] He was trained as a translator in the German language during World War II, but was not deployed. After the end of the war, he returned to Harvard and received his BA in 1946.[5] He then attended graduate school at Columbia University where he studied anthropology.[3] He shortened his name to Rabin soon after.[1]

Peace Walk (1960—1961)

Rabin originally participated with the Committee for Non-Violent Action (CNVA) in the earliest of the American-Soviet Peace Walks known as the "San Francisco to Moscow Walk for Peace" from 1960 to 1961. He began working with the group as a photographer alongside a documentary film crew, but eventually joined the movement himself.[1] The group marched across the United States calling for nuclear disarmament, traveling to Britain, Belgium, and West Germany. France would not allow them to enter the country, but they were permitted to travel to Moscow via East Germany and Poland.[6] The attempt at citizen diplomacy was widely covered by most major media outlets. The Associated Press reported that Rabin and other peace activists had tea with Nina Kukharchuk-Khrushcheva, the First Lady of the Soviet Union, in Moscow, in October 1961. The group discussed disarmament, and asked the First Lady to consider setting a good example for other nations by disarming their weapons. She politely declined.[7]

Upon his return, he documented his experience in an essay for Liberation magazine in November 1961 titled "How We Went". In the essay, Rabin describes the peace walk with mixed results. They were able to reach people in many countries, but the ideological barrier with the Soviets was impenetrable. "We proposed that they undertake unilateral disarmament and that in the spirit of individual responsibility, each Soviet citizen who regarded war as intrinsically evil should on his own initiative abstain from all phases of military activity, including civilian labor in armaments industry."[8] In response, the peace delegation was laughed at by the Russians. "The Soviets," writes Rabin, "are determined to maintain their position of military strength—in defense, as they habitually allege, of the peace and of their territorial integrity—as long as their appeal for complete and general disarmament, multilaterally implemented, goes unheeded...As persons affected by the Gandhian and Christian traditions of nonviolence, we Peace Walkers found this disharmony of the Soviet position harsh to our ears. How can one simultaneously protest that one loves peace and avow implacable hatred and annihilation of a prospective enemy?"[8]

Civil Rights, Vietnam War (1961—1968)

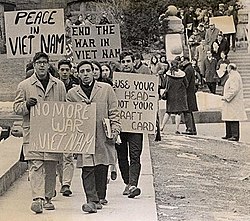

After completing the American-Soviet Peace Walk, Rabin returned to the United States and settled in Greenwich Village, where he met his future wife Helen at a New York meeting for a General Strike for Peace in 1961. Helen was then working at the Greenwich Village Peace Center in her downtime while pursuing her studies at Barnard College. They began having picnics at Washington Square Park and going to dances together. Both protested in favor of the civil rights movement and against the Vietnam War (1955–1975).[1] In 1964, he spoke out in the journal Science along with other academics during the so-called Ingle incident, when physiologist Dwight Ingle expressed prejudicial beliefs about Black Americans.[9] That same year, Jules and Helen were first arrested together as a couple while protesting against discriminatory hiring at the New York World's Fair.[1] Also in 1964, Rabin's public opposition to the Vietnam War was first entered into the Congressional Record by Senator Wayne Morse (D-OR). Morse was one of the few American politicians to oppose the war at the time.[10]

By 1965, Rabin was working at the Village Peace Center and collaborating with writers like Grace Paley.[11] Rabin's first hand accounts of the 1966 anti-Vietnam War marches in New York City was covered by Liberation magazine and WIN Peace & Freedom Through Nonviolent Action in the United States and in the pacifist magazine Peace News in Britain. He notes the increasing theatricality and use of large, oversized puppets by Peter and Elka Schumann with their Bread and Puppet Theater in the anti-war protests beginning in late 1965.[12] Coverage by Peace News refers to the "carnival"-like atmosphere, an idea that would later become known as tactical frivolity. Just before the Summer of Love the next year, Rabin observes the mood of the crowd compared to his 1961 peace walk, speaking to what he perceived as the "gospel of love that walked with us in the clear autumn sun".[13] Rabin also mentions that he carried his child [Hannah] on his shoulders during the protest, and that she enjoyed herself due to the float-like spectacle of the protest-turned-parade.[13] By April of 1966, Peace News reported that the American use of puppets in anti-war protests documented by Rabin had found its way to the Easter March at Trafalgar Square, noting the use of a puppet design by satirical cartoonist Gerald Scarfe depicting then-president Lyndon B. Johnson.[12]

In 1968, along with hundreds of other prominent Americans, Rabin signed the "Writers & Editors War Tax Protest" as a form of resistance to the war tax, with signers "refusing to pay" a proposed income tax surcharge that president Johnson said was needed in August 1967 to fund weapons and equipment to continue fighting the war in Vietnam.[14] The signatures appeared in the New York Post on January 30 of that year, with Rabin's name listed between writer Thomas Pynchon and mathematical psychologist Anatol Rapoport. The Federal Bureau of Investigation took notice and created a case file on the protest.[15] At some point, Rabin began supporting RESIST, a group that was formed to provide grants to grassroots activist organizations involved in the anti-war movement, but records indicate he was inactive by 1976.[16]

Goddard College (1968—1977)

In 1968, Rabin and his wife Helen moved from New York City to Marshfield, Vermont,[3] in part, due to the influence of the back-to-the-land movement.[17] In Vermont, he taught anthropology at Goddard College in the small town of Plainfield, for nine years.[3] Goddard, a progressive college originally founded by Christian universalists, was known for using evaluations instead of grading, and took its inspiration from educational reformer John Dewey (1859–1952). Fifty miles away from Burlington, the most populous city in the state, Goddard was built on an old dairy farm in the mountains. It drew members of the counterculture who sought to pursue the freedom afforded by a liberal curriculum and independent study.[18] Among one of Rabin's notable students at Goddard was playwright David Mamet.[19]

With the backdrop of the 1973 oil crisis looming large,[18] Rabin taught classes in an experimental social ecology studies program under environmental philosopher Murray Bookchin in 1974, considered the only program of its kind at the time. The program was said to explore "alternative technologies, a no-growth economics, organic agriculture, urban decentralization, the politics of ecology, and the design and construction of experimental models of wind, solar and methane-powered energy production."[18] In 1977, Rabin's job was eliminated by the college.[20]

Upland Bakers (1978—2002)

In 1971, Jules took a sabbatical from Goddard and traveled to Europe with Helen. They spent ten days visiting a commune known as the Community of the Ark in southern France.[21][α][23] The Ark was located in a small village known as La Borie Noble in the mountains of Occitanie, between Beziers and Millau.[24] A small community of more than 100 people,[23] the people in the Ark lived a simple life similar to peasants from the 18th century. Key to their diet and culture was the baking of country-style bread (pain de campagne) in a masonry oven, producing large round loafs (miche).[23] "They didn't speak of bread as holy, but they treated it as a holy object", Rabin remembered.[1]

Back home in Vermont, Rabin and his wife, who had formerly lived in a small shepherd's-like cabin on a farm near Goddard,[25] now had two children. They built a New England style farmhouse for their growing family in 1975.[26] They also built their own stone wood-fired oven from 75 tons of fieldstone based on the one they saw in 1971. At the time, an engineer provided them with a drawing schematic of the original French oven.[21] They had a dream of inviting their local community to join them in using it as a community oven just like the one at the Ark. They soon realized that this was not going to happen. Unlike the French countryside, the rural population of Vermont was too spread out among the hilly terrain. A year after building the new oven, Rabin lost his job at Goddard.[20] To make ends meet, they decided to sell bread from the oven that they built.[27] In 1978,[28] after building a small bakery behind their house and buying a mixer, they were licensed by the authorities and Upland Bakers was born.[23] Their traditional masonry oven is made from salvaged firebrick. It is heated by an initial wood fire after which the coals are removed and the oven cleaned out. The retained heat in the masonry is enough to bake bread for seven hours, giving it a unique, crusty sourdough finished product.[24]

Their bread is made only from flour, salt, water, and a sourdough starter;[27] no eggs, milk, or fat are used. They use unbleached white bread flour and milled rye or wheat flour. Their wheat bread uses whole grain and is organic. The dough is naturally leavened.[23] They used to work 40-hour work weeks with the couple sharing many of the tasks. Without plumbing, they needed to bring in water for the dough and wood for the oven. A typical week would find them producing 350 pounds of bread two days a week, preheating the oven on Tuesday, and baking on Wednesday and Thursday. They would begin by baking ten loaves at a time early in the day, moving to forty by the end of the day. This would produce about 250 loaves for each day, with distribution and sales at stores in Plainfield and Montpelier, on Thursday and Friday.[23] Chef Michel LeBorgne used Upland Bakers sourdough in dishes at the New England Culinary Institute. One dish called for serving it with local goat cheese produced in Brookfield.[29]

The Rabins ran their business lean and simple, keeping costs down with no rent to pay for a storefront and without selling at retail. In addition, market demand for their product was higher than what they could supply. Many of their neighbors helped to deliver the product to stores saving them money on delivery.[23] In 1987, The New York Times pointed to Upland Bakers as one of the major contributors to the then-ongoing renaissance of rustic bread in the United States.[24] In 1997, Rabin described his motivation in keeping the business small, local, and community focused: "Down familiar roads, five, ten, twenty miles away, live the various people who eat our bread. Two hundred times a day or so, our bread shows up on different tables. The bread has made the life of this jumble of hills and valleys a thread more convivial."[27] The Rabins retired from baking in 2002.[20] In 2014, Rabin, his wife, and daughter revived their business and began selling bread on Fridays at the Plainfield Farmers Market.[30]

Iraq War, Gaza War (2002—present)

During the Iraq War, Rabin started a weekly peace vigil outside of the Montpelier Federal Building which he continued for nine years.[31] His peace vigil was featured on the January 20, 2006, "Down by the Riverside" program on Montpelier community access television.[32] Rabin marked his 100th birthday on April 6, 2024. To celebrate, he asked his friends to join in a protest of the Gaza war in downtown Montpelier.[33] He has advocated on behalf of the Palestinians for more than two decades.[4] His birthday was celebrated by Vermont State Senator Andrew Perchlik with S.C.R.12 (Act R-265), which recognized Jules and Helen as "proponents of a just reconciliation between Arabs and Jews in the Middle East".[34]

Personal life

Rabin has identified as an atheist since at least the early 1960s.[6] He also identifies as culturally Jewish. In Vermont, the Rabins co-founded the Plainfield Community Seder, a Passover celebration ongoing since 1973.[35] Rabin grew up speaking Yiddish with his family, but does not read Hebrew and does not involve himself in issues directly related to the Jewish community.[4] He also speaks French, German, and Spanish.[6]

The Rabins have also been involved as volunteers with the Bread and Puppet Theater in Vermont.[2] In the 2010s, Rabin was frequently a Sunday morning guest on the "Curse of the Golden Turnip", a radio show about farming and gardening on WGDR (91.1 FM) community radio.[25]

Rabin leads a disciplined life beginning with a breakfast made from whole oats or barley, followed by cutting firewood, and regular use of a rowing machine.[36] He was able to do 50 push-ups a day until he was 95. At 100 years of age, he is only able to do 10.[37] His wife Helen is an artist who is active with the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom and is a member of the Raging Grannies.[23] They have two daughters, Hannah and Nessa.[3] Their daughters, along with five of their friends, founded the Children's Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in 1981. They attempted to meet with then-president Ronald Reagan, but the White House allegedly ignored them.[38] Nessa is a union baker and pastry chef.[20]

Notes

- ^ In the book The Community of the Ark, author Mark Shepard documents the role of artisan baking, noting the importance of bread labor as a guiding philosophy within the group.[22]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Pasanen, Melissa (August 7, 2024). "Marshfield's Jules Rabin Celebrates a Century of Intellectual Curiosity, Trailblazing Bread and Peace Activism". Seven Days. Retrieved March 20, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Gainza, Joseph (April 5, 2024). "Rabin turns 100". Barre Montpelier Times Argus. Retrieved March 23, 2025..

- ^ a b c d e Goodman, David (April 10, 2024). "Vermont Conversation: Peace activist Jules Rabin on his century of raising hell and raising bread". VTDigger. Archived from the original on September 20, 2024. Retrieved March 20, 2025.

- ^ a b c Wallach, Steven (August 3, 2002). "Cover Story: Jules Rabin's conscience" Archived 2025-03-23 at the Wayback Machine. Rutland Herald. Retrieved March 22, 2025.

- ^ Rabin, Jules (1987). "Doing and Departing". Harvard Magazine. 90: 14.

- ^ a b c Lyttle, Bradford (1966). You Come with Naked Hands: The Story of the San Francisco to Moscow Walk for Peace. Greenleaf Books. pp. 58, 73, 83, 241. ISBN 0934676089. OCLC 3216677.

- ^ "Mrs. Kruschev Said Russia Isn't Building Bomb Shelters". Associated Press. Great Bend Daily Tribune. Great Bend, Kansas. October 5, 1961.

- "'Disarm,' Pacifists Ask Mrs. K." Meriden Record. Associated Press. October 7, 1961. Retrieved March 26, 2025.

- ^ a b Rabin, Jules (1964) [1961]. "How We Went". In Goodman, Paul (ed.). Seeds of Liberation. George Braziller. pp. 151–161. OCLC 557446565.

- Rabin, Jules (November 1961). "How We Went". Liberation. Vol. 6, no. 9. pp. 11–15.

- ^ Middleton, Peter (2015). Physics Envy: American Poetry and Science in the Cold War and After. University of Chicago Press. pp. 247–248. ISBN 9780226290003. OCLC 902656832.

- ^ Rabin, Jules (August 21, 1964). "88th United States Congress". Congressional Record. Vol. 110. United States Government Printing Office. p. 21020.

- ^ Paley, Grace (January 28, 1965). "Dr. Vo's Quiet Quest for Peace in Vietnam". The Village Voice. p. 3. Retrieved March 26, 2025.

- ^ a b Rabin, Jules (April 22, 1966). "Peter Schumann's Puppet 'Vietnam' Theatre". Peace News.

- ^ a b "Carnival of Shame?". Peace News. January 13, 1967. p. 4.

- ^ Weisberg, Harold. Writers and Editors Protest. The Weisberg Archive, Beneficial-Hodson Library, Hood College. National Security Internet Archive..

- ^ Writers and Editors War Tax Protest (January 30, 1968). "If a thousand men were not to pay their tax-bills this year". New York Post.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation (February 21, 1968). Writers and Editor War Tax Protest.

- ^ Resist (September 26, 1976). "Resist Board Meeting". Board Meeting Minutes. Watkinson Library Special Collections. Trinity College Digital Repository.

- ^ Golub, Abby (May 16, 2014). "On Neoliberalism and Bread". The Cornell Progressive. Vol. 14, no. 8. Retrieved March 26, 2025.

- ^ a b c Biehl, Janet (2015). Ecology or Catastrophe: The Life of Murray Bookchin. Oxford University Press. pp. 149, 156, 159, 173. ISBN 9780199342488. OCLC 857754193.

- ^ Mamet, David. "Foreword". River Run Cookbook: Southern Comfort from Vermont. HarperCollins. pp. ix–x. ISBN 9780060195250. OCLC 44128233.

- ^ a b c d Kalish, Jon (2014). "Legendary Vermont Bakers May Stop Selling Beloved Sourdough Bread". All Things Considered. National Public Radio. Archived from the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved March 20, 2025.

- ^ a b "Baking Bread in a Hand-Made Oven". The Blade. Toledo, Ohio. Christian Science Monitor Service. March 12, 1986. p 24.

- ^ Shepard, Mark (1990). The Community of the Ark. Ocean Tree Books. pp. 18–19, 25–26, 29. ISBN 9780943734286. OCLC 31706089.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wing, Daniel; Scott, Alan (1999). The Bread Builders: Hearth Loaves and Masonry Ovens. Chelsea Green Pub. Co. pp. 18–22. ISBN 9781890132057. OCLC 39906018.

- ^ a b c Fabricant, Florence (November 4, 1987). "America Whets Its Appetite For Hearth-Baked Breads". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 12, 2025. Retrieved March 20, 2025.

- ^ a b Rowell, Leslie. "Oral history interview with Michele Clark". Vermont 1970s Counterculture Project Oral Histories. Vermont Historical Society. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved March 25, 2025. Event occurs at 22:11—29:33.

- ^ Clark, Sam (1996). The Real Goods Independent Builder: Designing & Building a House Your Own Way. Chelsea Green Publishers. pp. 1, 2, 82. ISBN 9780930031855. OCLC 35086196.

- ^ a b c Budbill, David (Summer 1997). "Letter from Plainfield Vermont". Regional Review. Vol. 7. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. Retrieved March 22, 2025.

- ^ Galloway, Anne (August 21, 2005). "Works of Helen Rabin, Andrew Kline at Blinking Light". Rutland Herald. Retrieved March 22, 2025.

- ^ LeBorgne, Michel (2009). No Crying in the Kitchen: A Memoir of a Teaching Chef. Public Press. pp. 156–157. ISBN 9780976452072. OCLC 858920391.

- ^ Nemethy, Andrew (July 20, 2014). "From the Rabins, a summer revival of the sourdoughs that changed Vermont". Rutland Herald. Archived from the original on September 20, 2024. Retrieved March 20, 2025.

- ^ Vance, Keith (December 31, 2011). "Vermont couple marks final peace vigil" Archived 2025-03-23 at the Wayback Machine. Rutland Herald. Retrieved March 22, 2025.

- ^ "Linda Leehman Progressive Video Collection, 1993-2009" (PDF). Vermont Historical Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 30, 2018. Retrieved March 25, 2025.

- ^ Goodman, David (April 16, 2024). "Vermont Conversation: Peace Activist Jules Rabin". Hardwick Gazette. Archived from the original on December 9, 2024. Retrieved March 20, 2025.

- ^ Vermont General Assembly. (2024). S.C.R.12, Act R-265: Congratulating the educator, baker, peace activist, and writer Jules Rabin of Marshfield on his 100th birthday.

- ^ Gram, David. "Annual seder fosters cultural, community identity". The Telegraph. Associated Press. p. 6. Retrieved March 26, 2025.

- ^ Kalish, Jon (May 4, 2024). "This 100-year-old Jewish activist is speaking up again — this time about Gaza". The Forward. Archived from the original on October 12, 2024. Retrieved March 20, 2025.

- ^ "Jules Rabin doing push-ups". Seven Days. Retrieved March 25, 2025.

- ^ Van Ornum, William; Van Ornum, Mary Wicker (1984). Talking to Children About Nuclear War. Continuum. pp. 28–32. ISBN 9780826402486. OCLC 10277620.

- La Farge, Phyllis (1987). The Strangelove Legacy: Children, Parents, and Teachers in the Nuclear Age. Harper & Row. pp. 66–70. ISBN 9780060156992. OCLC 14166400.

External links

- "Our state of food, our state of mind" (1979 lecture)

You must be logged in to post a comment.