In physics, a perfect fluid or ideal fluid is a fluid that can be completely characterized by its rest frame mass density and isotropic pressure .[1] Real fluids are viscous ("sticky") and contain (and conduct) heat. Perfect fluids are idealized models in which these possibilities are ignored. Specifically, perfect fluids have no shear stresses, viscosity, or heat conduction.[1] A quark–gluon plasma[2] and graphene are examples of nearly perfect fluids that could be studied in a laboratory.[3]

Examples

Perfect fluids are used in general relativity to model idealized distributions of matter, such as the interior of a star or an isotropic universe. In the latter case, the symmetry of the cosmological principle and the equation of state of the perfect fluid lead to Friedmann equation for the expansion of the universe.[4]

A flock of birds in the medium of air is an example of a perfect fluid without relativistic symmetry; an electron gas in a solid with possible electron-phonon coupling is also modeled as a perfect fluid.[1]

D'Alembert paradox

In classical mechanics, ideal fluids are described by Euler equations. Ideal fluids produce no drag according to d'Alembert's paradox. If a fluid produced drag, then work would be needed to move an object through the fluid and that work would produce heat or fluid motion. However, a perfect fluid can not dissipate energy and it can't transmit energy infinitely far from the object.[5]: 34

Relativistic formulation

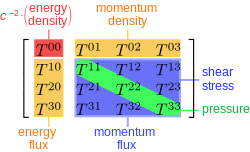

In space-positive metric signature tensor notation, the stress–energy tensor of a perfect fluid can be written in the form

where U is the 4-velocity vector field of the fluid and where is the metric tensor of Minkowski spacetime.

In time-positive metric signature tensor notation, the stress–energy tensor of a perfect fluid can be written in the form

where is the 4-velocity of the fluid and where is the metric tensor of Minkowski spacetime.

This takes on a particularly simple form in the rest frame

where is the energy density and is the pressure of the fluid.

Perfect fluids admit a Lagrangian formulation, which allows the techniques used in field theory, in particular, quantization, to be applied to fluids.

See also

References

- ^ a b c de Boer, Jan; Hartong, Jelle; Obers, Niels; Sybesma, Waste; Vandoren, Stefan (2018-07-17). "Perfect fluids". SciPost Physics. 5 (1): 003. arXiv:1710.04708. Bibcode:2018ScPP....5....3D. doi:10.21468/SciPostPhys.5.1.003. ISSN 2542-4653.

- ^ WA Zajc (2008). "The fluid nature of quark–gluon plasma". Nuclear Physics A. 805 (1–4): 283c – 294c. arXiv:0802.3552. Bibcode:2008NuPhA.805..283Z. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2008.02.285. S2CID 119273920.

- ^ Müller, Markus (2009). "Graphene: A Nearly Perfect Fluid". Physical Review Letters. 103 (2): 025301. arXiv:0903.4178. Bibcode:2009PhRvL.103b5301M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.025301.

- ^ Navas, S.; et al. (Particle Data Group) (2024). "Review of Particle Physics". Physical Review D. 110 (3): 1–708. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.110.030001. hdl:20.500.11850/695340. 22.1.3 The Friedmann equations of motion

- ^ Landau, Lev Davidovich; Lifšic, Evgenij M. (1959). Fluid mechanics. Their course of theoretical physics. London: Pergamon Press. ISBN 978-1-4831-4050-6.

Further reading

- S.W. Hawking; G.F.R. Ellis (1973), The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time, Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-20016-4, ISBN 0-521-09906-4 (pbk.)

- Jackiw, R; Nair, V P; Pi, S-Y; Polychronakos, A P (2004-10-22). "Perfect fluid theory and its extensions". Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General. 37 (42): R327 – R432. arXiv:hep-ph/0407101. doi:10.1088/0305-4470/37/42/R01. ISSN 0305-4470. Topical review.

![{\displaystyle \left[{\begin{matrix}\rho _{e}&0&0&0\\0&p&0&0\\0&0&p&0\\0&0&0&p\end{matrix}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/875c5a58c98b9d041855127d579206c801800fe0)

You must be logged in to post a comment.