Oleksiy Mykolaovych Beketov (Ukrainian: Олексій Миколайович Бекетов; 3 March 1862, Kharkiv, Russian Empire — 23 November 1941, Kharkiv, Ukrainian SSR) was a Ukrainian[1] architect, Honored Artist of Ukraine,[2] who made significant contributions to the architectural landscape of Kharkiv and beyond, primarily working in the Neoclassical, Neo-Renaissance, and Art Nouveau styles. He was an honorary Professor at the St. Petersburg Imperial Academy of Arts from 1894.

Biography

Oleksiy Mykolaovych Beketov was born on February 19 (March 3), 1862, in the city of Kharkiv.[1] The Beketov family is probably of Turkic or Circassian origin.[3] Oleksiy Beketov was the son of famous Russian-Ukrainian chemist Nikolay Beketov,[4] a noted Professor of chemistry at the Imperial University of Kharkiv.[5] His father came from a Russian noble family with roots from the Penza Governorate, Nikolay Beketov was born in Alferovka (now Beketovka, Penza Governorate), than moved to Kharkiv.[6] When he was elected to the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences, he moved to St. Petersburg, where he died in 1911. His mother Olena Karlivna Milhoff (Beketova) was daughter of the Katerynoslav pharmacist.[5]

He studied at the local realschule and a private art school, operated by Maria Raevskaia-Ivanova in Kharkiv.[7] In 1882, he enrolled in the Imperial Academy of Arts, where he studied with David Grimm and Alexander Krakau; graduating in 1888 with a degree in architecture.[8] He graduated with a gold medal and defended his thesis on the topic "The Station at the Sea Baths on the Black Sea".[9] During that same period, he worked with Maximilian Messmacher on several projects, including the palace of Grand Duke Michael Mikhailovich.

After his studies, he was offered a job in Russia, in particular at the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts, but he wrote that he wanted to "live and give all his strength to his hometown ... I stood, looked at the palaces and remembered our Kharkiv - I felt with all my heart that I wanted to return and give all my strength to my native city".[6] Therefore, he soon returned to Kharkiv and from 1890 taught architectural design and drawing at the Kharkiv Practical Technological Institute.[10][11] From 1892 he taught a course in building art and architecture, and in 1898 he joined in compiling the programs and teaching a course in the history of architecture, as well as supervising the diploma and course design. In 1909, he published the book "Architecture. A Course of Lectures Given at the Kharkiv Institute of Technology Named After Emperor Alexander the Third". In 1894, he was awarded the title of "Academician" for his work on Kharkiv Public Library (1899–1901), what is now known as the Kharkiv Korolenko State Scientific Library.[8][12] His first project to be implemented was the building of the Commercial School.[10] In addition to simply designing the building, he also managed and supervised the construction, performing the work of a foreman. He continued to work in the same way.[10][13]

The Beketov family, in particular Oleksiy and his father Nikolay, were acquainted with the famous Alchevsky family of Ukrainian educators and activists. The Alchevsky family, together with Nikolay Beketov, were among the founders of the Kharkiv Society "Hromada", a national and cultural center of the Ukrainian intelligentsia.[1] In 1899 Oleksiy Beketov was married to Hanna Alchevska (1868-1931), daughter of the Ukrainian industrialist, banker, public figure, and philanthropist, Oleksiy Alchevsky and his wife, Khrystyna, an Ukrainian educator and public education organizer.[1] Therefore, the projects of the most important buildings that served the cause of public education for Kharkiv were carried out by O. M. Beketov free of charge. These include the project of the Public Library (1899–1901, now the V. G. Korolenko Kharkiv State Scientific Library)[12] and the project of the building of the Sunday Women's School of Khrystyna Alchevska (1896, now the Exhibition Hall of the Kharkiv Art Museum).[14] Also, the buildings of Oleksiy Alchevsky's banks: Zemelny (Land) and Torgovy (Trade) were built according to his designs. To master the specifics of bank construction, the architect visited France, Italy, and Germany, inspecting the layout of operating rooms, work areas, safes, and other premises of European banks. Beketov also built a private mansion for the Alchevskys in the style of Italian villas. In the courtyard of this mansion, the very first monument to Taras Shevchenko in Ukraine was erected in 1900.[15] The author of the monument is Ukrainian-Russian sculptor Volodymyr Beklemishev, who, like Beketov, graduated from the Kharkiv drawing school of Maria Raevskaya-Ivanova.[15][16]

Oleksiy and Hanna had four children: Khrystyna (1890-1972, graphic artist, specialized in etching. Author of memoirs about her uncle, the outstanding tenor Ivan Alchevsky, lived in Bulgaria), Mykola (1891-1964, by profession a sailor, died in Canada), Maria (1893-1921, died in Central Asia during an infectious epidemic), and Olena (1895-1990, served as her father's secretary and assistant, was the keeper of the archives of the Alchevsky and Beketov families. Buried in the city cemetery No. 2 (Kharkiv)).[1][17][18] His grandson Fedir Semenovych Rofe-Beketov (1932) became a Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences,[19][20] and his great-granddaughter Olena Rofe-Beketova is a well-known public figure, defender of the city's architectural heritage, volunteer during the Russian-Ukrainian war and activist.[21][22][23][24][25][26][27][1] Currently, the architect's descendants live in one of the apartments in the building that the architect built in 1912 on Darwin Street after the economic crisis. Beketov's friend, the prominent Ukrainian artist Mykola Samokysh, also lived in this building.[28]

After the Soviet occupation of Ukraine began, Beketov remained in Kharkiv. Most of his property was nationalized by the Soviet authorities. Since 1920, in addition to KhTI, he worked as the main architect of the Kharkiv Art School. Since 1929, he became a professor of architecture at the Kharkiv Mechanical Engineering Institute.[10] Since 1935, he has been working at the Kharkiv Institute of Municipal Engineering Engineers (now the O. M. Beketov Kharkiv National Academy of Urban Economy), where he became a full-time professor at the Department of Architectural Design. He worked in this position until September 22, 1941.[10]

In 1939, he was named an Honored Artist of Ukraine.[29]

It is known that until the last days of his life, the architect led an active lifestyle, played tennis, and in August 1941, when the city was still under the control of the Soviet army, he submitted a request to the institute to return to teaching.[1][10] Later, he had a stroke, and in his last days he lay in bed.[5][1] Oleksiy Mykolayovych Beketov died on November 23, 1941, in Kharkiv, occupied by the Nazi army, aged seventy-nine.[29] He was initially buried in the honorary Ivano-Usiknovensky cemetery. In the 1970s, the city authorities decided to demolish the cemetery, where many prominent citizens were buried, along with the graves.[30] Oleksiy Beketov's grave, along with some others, was moved to the 13th city cemetery, where it is located to this day.[31][32] The gravestone, which was made in 1946, was also moved.[33] The grave of the outstanding Ukrainian architect is a monument of history of all-Ukrainian significance (protection number №200008-Н).[33]

Commemoration

- Streets

- Сommemorative plaque

- A plaque from the early 20th century has survived on the building of the former commercial school in Kharkiv, which was built according to his design.[36]

- A commemorative plaque has been installed in 1987 on the house on Darvina Street in Kharkiv, where he lived.[37] The old board was lost, and a new one was installed in 2001.[10]

- A commemorative plaque is installed on the library building in Kharkiv, which was built according to his design.[38]

- A plaque in his honor is installed on the building of the Mechnikov Institute in Kharkiv, was built according to his design.[39]

- A commemorative plaque in honor of the architect is installed on the courthouse building in Kharkiv, which was built according to his design.[40]

- The museum of the Kharkiv National Academy of Urban Economy has a memorial plaque in honor of the auditorium named after Beketov.

- It was also planned to install several plaques on other prominent buildings in Kharkiv.[41]

- Institutions named after Beketov

- Kharkiv National Academy of Urban Economy was named in honor of Oleksiy Beketov in 2013.

- In 1995, a new subway station on the Kharkiv Metro was named the Arkhitektora Beketova.[42]

- Auditorium No. 501 Kharkiv National Academy of Urban Economy was named after the architect in 1987.[10]

- Monuments

- On September 22, 2007, a monument to Oleksiy Beketov was unveiled in front of the building of the former Kharkiv National University of Civil Engineering and Architecture. The author of the monument is Seyfaddin Gurbanov.[43][44]

- On August 30, 2016, a monument to Oleksiy Beketov was unveiled in front of the building of the Kharkiv National Academy of Urban Economy. The authors of the monument are Oleksandr Ridny and Hanna Ivanova.[45]

- In 2001, a monument to the architect with his bust was erected in the Kharkiv House of Scientists, which was built as Beketov's own mansion.

- In 2002, a bust of Beketov was installed in the museum of the Kharkiv National Academy of Urban Economy.

- There is a stained glass window with his image at the "Arkhitektora Beketova" station of the Kharkiv Metro.

- Museums

- A section of the museum at the Kharkiv National Academy of Urban Economy is dedicated to the architect.

- His dacha in Alushta is now a museum.

- Some of Beketov's belongings are kept in the Kharkiv Historical and Art Museums.

- Other

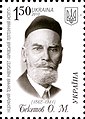

- In 2010, a postage stamp "Beketov Oleksiy Mykolaovych" was issued in Ukraine.[46]

- Several books have been written about Oleksiy Beketov. He also wrote his own autobiography and descriptions of his projects.[10]

Works

In Kharkiv, he built over 40 public and residential buildings.[1] He primarily worked in the Neoclassical, Neo-Renaissance, and Art Nouveau styles. He also utilized Neo-Moorish, Neo-Grec, and other styles.[47] In the 1920s and 1930s, several buildings were erected according to his designs in the Constructivist style. He participated in the competition for the construction of the Derzhprom building, but his project was not among the winners.[48] In 1905–1907, in collaboration with sculptor I. Andreoletti, he created the monument to V. N. Karazin, which is now located near the entrance to V. N. Karazin Kharkiv University.[49] Today, most of his buildings are architectural monuments of local significance in Ukraine.[33] A significant portion of his buildings were damaged during the Russian shelling of Kharkiv after the start of the full-scale invasion in 2022–2025.[50][51]

In addition to his architectural designs, he was an amateur artist, painting Crimean landscapes.[52] Many of his landscape paintings are in private collections. Alexey Dushkin, Yakov Lichtenberg, and Vasyl Krychevsky are some of his best-known students.

The name Beketov, "Beketov's buildings," or "Beketov's style" in the city of Kharkiv is often used as a generic term for all beautiful buildings.[53][54]

- Alexander Commercial School (1889–1901, now occupied by the Yaroslav Mudryi National Law University; 77 Hryhoriya Skovorody Street);

- Sunday Women's School of Khrystyna Alchevska (1896, the school belonged to his wife's mother, building damaged by Russian missile strike;[59] 18/9 Chernyshevska Street);

- Land Bank (1896–1898, the bank belonged to his father-in-law, now Kharkiv Automobile Transport Professional College, building damaged by Russian missile strike;[60] 28 Konstytutsiyi Square);

- Azov-Don Commercial Bank (1896, building damaged by Russian missile strike;[61] 14 Konstytutsiyi Square);

- Church of the Nativity of the Virgin (Kaplunivska, 1896–1912, destroyed in the 1930s; Kaplunivska Street);

- Trade Bank (1899, the bank belonged to his father-in-law; 26 Konstytutsiyi Square);

- Kharkiv Public Library (1899–1901, building damaged by Russian missile strike;[62] 18 Korolenko Lane);

- Building of judicial institutions (1899–1902, with the participation of architects Yuliy Tsaune and V. Khrustalyov, building damaged by Russian missile strike;[63] 36 Heroiv Nebesnoi Sotni Square);

- Kharkiv Society of Mutual Credit (1903–1905; 20 Pavlivska Square);

- Volga-Kama Bank (1907, now Kharkhiv State Puppet Theatre; 24 Konstytutsiyi Square);

- Anatomical Theater of the Kharkiv Women's Medical Institute (1910–1911; 8 Skrypnikivsky descent);

- Building of the Kharkiv Medical Society (1911–1913, now the Mechnikov Medical Institute; 14 Hryhoriya Skovorody Street);

- Sokolov Obstetrics and Gynecology Department of the Alexander Hospital (1912–1913;);

- Management of the North Donetsk Railway (1913, authors - S. Timoshenko, P. Shirshov, P. Sokolov, with consultation from O. Beketov; 4 Zbroyarska Street);

- Higher Women's Courses (1913–1915; 92 Myronosytska Street);

- Orphanage for noble orphans (1913–1915, now a building of the Yaroslav Mudryi National Law University; 84 Hryhoriya Skovorody Street);

- Commercial Institute (1914–1916, now Kharkiv National Technical University of Agriculture; 44 Alchevskykh Street);

- Shelter for elderly nobles (1914–1916; 4 Mykhaylya Semenka Street);

- Electrotechnical building of NTU "KhPI" (1928–1929; 2 Politekhnichna Street);

- Building for railway workers (1925–1936, also known as the "Liternyy House (Letter House, Літерний будинок)", from the Ukrainian word "Літера (Litera, Letter)"; 8/10в and 8/10a Yevhena Kotlyara Street);

- Residential building "Industrial Professor" (1934–1936; 17 Bahalia Street);

- "Voyenvid" (1938, Military Department Residential Building, Будинок Військового Відомства, author - P. Shpara, compiled with the advice of O. Beketov; 1 Borysa Chychybabina Street).

- Alchevsky Mansion (1893, mansion of his wife's family; 13 Zhon-Myronosyts Street);

- Own house on Zhon-Myronosyts Street (1896–1897, now Kharkiv House of Scientists, building damaged by Russian missile strike;[64] 10 Zhon-Myronosyts Street);

- Dmytro Alchevsky Mansion (1896, belonged to his wife's brother, later the girls' gymnasium, now a school; 13 Darvina Street);

- N. L. Zalesky Mansion (1897; 9 Skrypnyka Street).

- Sokolov Merchant's Mansion (1899, building damaged by Russian missile strike;[65] 17 Blahovishchenska Street);

- Mykola Somov Mansion (1900; 13 Maksymilianivska Street);

- P. V. Markov Merchant's Mansion (1901; 23 Darwin Street);

- P. V. Markov Merchant's Mansion (1902, building damaged by Russian missile strike;[66] 8/10 Kulykivsky Descent);

- Own house on Darwin Street (1902; 17 Darwin Street);

- Fotiy Pisnyachevsky Mansion (1903; 21 Darwin Street);

- The mansion of Olexander Iosefovich and the editorial office of the newspaper "Yuzhnyy kray" (1903; 13 Sumska Street)

- Mansion of engineer O.I. Fenin (1909; 19 Maksymilianivska Street)

- Ivan Yegorovich Ignatishchev Mansion (1912, now Kharkiv Art Museum, building damaged by Russian missile strike;[59] 11 Zhon-Myronosyts Street);

- Own house on Darwin Street (1912, his descendants live in one of the apartments; 37 Darwin Street).

- Kharkiv Literacy Society (1898, reconstructed in 1902; 26 Svobody Street);

- Council of the Congress of Miners of Southern Russia (1910–1913, reconstruction of the assembly hall; 18/20 Sumska Street);

- Workers' Society Building (1905, reconstructed in 1924; 77 Heorhia Tarasenka Street);

- Building of the State Bank (1897–1900, reconstructed in 1932; 1 Teatralnyy Square).

Not implemented or lost in Kharkiv

Beketov is the author of an unrealized project for the Kharkiv Opera House for 2,200 people.[69] The construction was canceled due to the outbreak of World War I. He also participated in competitions for the Derzhprom building (1925)[48] and the new building of Kharkiv University (1930).[70] In 1938–1939, the architect created a project to expand the library building, which was never implemented.[10]

In 1908, the "Fruit Rows" and "Golgotha Panorama" were built on Pavlivskyi Square in Kharkiv, designed by architect Beketov. The building was demolished to widen the road in the 1930s.[71] In 1898, O. Beketov designed the reconstruction of the house of G. I. Rubinstein. The house was probably destroyed in the middle of the 20th century.

- Metallurgical Plant of the Donetsk-Yur'evsk Metallurgical Society (Alchevsk, 4 Shmidt St.; 1895. Probably lost);

- Own dacha (Alushta; 1896);

- Katerynoslav Higher Mining College (Dnipro, 19 Yavornytsky Ave.; 1901–1912. Original appearance lost);

- Katerynoslav Higher Mining College (Dnipro, 19/2 Yavornytsky Ave.; 1901–1903);

- Management of the Katerynoslav Railway (Dnipro, 108 Dmytro Yavornytskyi Ave.; 1905–1907. The building was destroyed during World War II and later rebuilt with a changed appearance.);

- Diocesan Women's School (Lubny, 2 General Lyaskin St.; 1907-1908);

- Chamber of Judicial Institutions (Novocherkassk, 72, Platovskyi Ave.; 1907–1909);

- Branch of Volga Kama Commercial Bank (Rostov-on-Don, 55 Bolshaya Sadova St.; 1910);

- Theater with a revenue building (Simferopol, 15 Pushkina St., 1911);

- "Villa "Marina"" (Alushta, building of the sanatorium "Sea Corner"; 1912);

- Lubny District Court (Lubny, 19 Kuzina Square; 1912);

- Ascension Church (Trostianets, 53 Voznesenska St.; 1913. The building repeats the Ozeryanska Church in Kharkiv);

- Diocesan Women's School (Belgorod; 1915. Destroyed);

- Peasant sanatorium named after VUTSVK (Khadjibey; co-author M. Pokorny, 1928–1933);

- 5-story residential building for employees of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine (Bolsheviks) (Kyiv, 9 Hrushevskoho St.; 1935).

Gallery

-

Building of the Kharkiv Medical Society (1911–1913)

-

Land Bank (1896–1898)

-

Land Bank (1896–1898). Facade

-

Kharkiv Public Library (1899–1901)

-

Sokolov Merchant's Mansion (1899)

-

Commercial Institute (1914–1916). Interiors

-

Dmytro Alchevsky Mansion (1896)

-

Alexander Commercial School (1889–1901)

-

Own house on Zhon-Myronosyts Street (1896–1897)

-

Orphanage for noble orphans (1913–1915)

-

P. V. Markov Merchant's Mansion (1901, Darwin Street);

-

Building of judicial institutions (1899–1902)

-

Mykola Somov Mansion (1900)

Legacy

-

Station Arkhitektora Beketova on Kharkiv Metro

-

Monument to Beketov in Kharkiv unveiled in 2016. Kharkiv National University of Urban Economy after Russian rocket strike, February 5, 2023

-

Monument to Beketov in Kharkiv

-

Stained glass window with his image in Kharkiv

-

Plaque from the early 20th century in Kharkiv

-

A commemorative plaque in Kharkiv

-

A commemorative plaque in Kharkiv

-

A commemorative plaque in Kharkiv

-

His grave in Kharkiv. A historical monument of all-Ukrainian significance

-

Postage stamp "Oleksiy Mykolaovych Beketov" (2010)

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Цьомик, Ганна (2024-11-17). ""Харків спадковий". Алчевські-Бекетови — не знищений рід. Оповідь спадкоємиці". Суспільне | Новини (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Monument to a famous architect unveiled in Kharkiv". thekharkivtimes.com. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ Петров П. Н. История родов русского дворянства. Том I. СПб.: Герман Гоппе, 1886. - VIII, 400 с.

- ^ "БЕКЕТОВ ОЛЕКСІЙ МИКОЛАЙОВИЧ". resource.history.org.ua. Archived from the original on 29 August 2020. Retrieved 2019-09-28.

- ^ a b c "Дві родини – Фонд родини Алчевських-Бекетових". www.a-b.foundation (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ a b Цьомик, Ганна (2024-11-17). ""Харків спадковий". Алчевські-Бекетови — не знищений рід. Оповідь спадкоємиці". Суспільне | Новини (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2025-03-05.

- ^ "1862 - народився Олексій Бекетов, архітектор". uinp.gov.ua. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ^ a b Діячі науки і культури України : нариси життя та діяльності. Київ: Книги - ХХ. 2007. p. 31. ISBN 978-966-8653-95-7.

- ^ a b "Історія відомої харківської персони - ikharkovchanin.com" (in Ukrainian). 2023-02-02. Retrieved 2025-03-05.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Davydova, N.B.; Statkus, V.O.; Shanhei, O.M. (2023). Олексій Миколайович Бекетов: життя і творчість (1862–1941). Біобібліографічний покажчик (in Ukrainian). Kharkiv: Kharkiv National University of Urban Economy named after O. M. Beketov.

- ^ T. F. Davidovich; "Архитектор А. Н. Бекетов. Жизнь и творчество" (Life and Works), In: Academia. Architecture and Construction, 2018

- ^ a b "Научная библиотека им. Короленко — Харьков Манящий". moniacs.kh.ua. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Земельний банк | Харківська мапа". khuamap.netlify.app. Retrieved 2025-03-05.

- ^ "Недільна жіноча школа Христини Алчевської | Харківська мапа". khuamap.netlify.app. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ a b "Перший пам'ятник Шевченкові | Харківська мапа". khuamap.netlify.app. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Скульптор Владимир Беклемишев, 1861-1920".

- ^ "Ivan Alchevsʹkyĭ : spohady, materialy, lystuvanni︠a︡ (Livre, 1980) [WorldCat.org]". web.archive.org. 2021-07-09. Retrieved 2025-02-28.

- ^ "Дві родини – Фонд родини Алчевських-Бекетових". www.a-b.foundation (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2025-03-05.

- ^ "Рофе-Бекетов Ф.С. и Песчанский В.Г. // В.В. Ерёменко. О себе и моих учителях, колегах, друзьях". Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020. Archived 2020-03-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Чайка, Майя (29 August 2016). "Алчевские. Память сердца". Харьковские Известия. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020. Archived 2020-03-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Харківський національний університет міського господарства імені О. М. Бекетова. Пам'ятник великому зодчому і педагогу О.М. Бекетову". 29 March 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-03-29. Retrieved 29 March 2020. Archived 2020-03-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Стрельник, Ирина (18 June 2018). "Памятники архитектуры и истории нужно не охранять, а сохранять". Вечерний Харьков. Archived from the original on 2020-03-29. Archived 2020-03-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Трансформация волонтерства: от ящиков с едой к масштабным фестивалям". Накипело (in Russian). 6 February 2017. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "Активісти Харкова та 9 міст об'єднуються для захисту архітектурних пам'яток". Справжня варта. 15 January 2018. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Гуш, Юлія (7 March 2019). "Будинок зі шпилем у небезпеці: Як безкультур'я та жадоба знищують старий Харків". Depo.ua. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Бойко, Юлія (15 January 2019). "У Харкові пройшов щорічний вертеп-фест (відео)". Медиа группа «Объектив». Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Верещака, Марина (12 January 2020). "Понад 1,5 тисячі колядників пройшлися центром Харкова". Суспільне. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "Будинок архітектора Олексія Бекетова | Харківська мапа". khuamap.netlify.app. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ a b Тимофієнко, В. І. (2003). "Бекетов Олексій Миколайович". Енциклопедія Сучасної України (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Іоано-Усікновенське кладовище | Харківська мапа". khuamap.netlify.app. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Могила Бекетова Олексія Миколайовича (кладовище закрите для відвідувань) | Харківська мапа". khuamap.netlify.app. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "13 міське кладовище (закрите для відвідувань) | Харківська мапа". khuamap.netlify.app. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ a b c Наказ Міністерства культури та інформаційної політики України від 4 червня 2020 року № 1883 «Про занесення об'єктів культурної спадщини до Державного реєстру нерухомих пам'яток України»

- ^ Machulin, Leonid (2007). Улицы и площади Харькова. Kharkiv. pp. 72–73.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "ул. Бекетова". streets-kharkiv.info (in Russian). Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Історія Харкова у пам'ятних дошках: Будівля Харківського комерційного інституту". Історія Харкова у пам'ятних дошках. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Історія Харкова у пам'ятних дошках: Бекетов О. М." Історія Харкова у пам'ятних дошках. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Історія Харкова у пам'ятних дошках: Будівля Харківської громадської бібліотеки". Історія Харкова у пам'ятних дошках. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Історія Харкова у пам'ятних дошках: Мечниковський інститут". Історія Харкова у пам'ятних дошках. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Історія Харкова у пам'ятних дошках: Будівля судових установ". Історія Харкова у пам'ятних дошках. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "На домах архитектора Бекетова установят таблички с QR-кодами". stroyobzor.ua (in Russian). Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Архітектора Бекетова". www.metro.kharkiv.ua. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ Свобода, Радіо (2008-02-05). "Пам'ятник архітектору Бекетову допомагатиме харківським студентам". Радіо Свобода (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2025-03-05.

- ^ "Пам'ятники Бекетову | Харківська мапа". khuamap.netlify.app. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Новый памятник Бекетову". Харьков - куда б сходить? (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2025-03-05.

- ^ Мулик Я. Каталог поштових марок України (1918—2011). — 2-ге. — Дрогобич : «Дрогобич Коло», 2012. — 190 с. — ISBN 978-617-642-004-0.

- ^ "Бекетов, Олексій Миколайович". ВУЕ (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ a b "Наш Держпром: яким міг бути символ Харкова". Слобідський край (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Бекетов Олексій Миколайович (1862-1941) | Харьковский областной совет молодых ученых и специалистов". scientists.kharkov.ua. Archived from the original on 28 June 2019. Retrieved 2019-09-28.

- ^ Богдан, Аліна Гаєвська, Руслана (2022-06-27). "У Харкові від обстрілів РФ пошкоджені близько 10 бекетівських будівель". Суспільне | Новини (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2025-02-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ УІНП. "1862 - народився Олексій Бекетов, архітектор". УІНП (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ a b c "Про О.М. Бекетова". museum.kname.edu.ua. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Власти Харькова обсуждают с архитекторами восстановление города". nerukhomi.ua (in Russian). 2025-03-02. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Прогулянка улюбленим містом. "Бекетівські" будинки Харкова". turne.ua. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ a b "Пошук | Харківська мапа". khuamap.netlify.app. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ a b "Головні архітектурні проєкти архітектора Бекетова в Харкові - kharkov-future.com.ua" (in Ukrainian). 2022-09-15. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Литерный дом — Харьков Манящий". moniacs.kh.ua. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ a b ngeorgij (2 December 2010). "Бекетовские дома в Харькове". Харьков: новое о знакомых местах. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ a b Рязанцева, Марина Верещака, Альона (2022-03-08). ""Картини російських художників рятуємо від їхнього народу": Харківський худмузей". Суспільне | Новини (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2025-02-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Земельний банк в деталях – Харків, що манить". moniacs.kh.ua. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Азовсько-Донський банк – Харків, що манить". moniacs.kh.ua. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ Кривко, Альона Рязанцева, Роман (2022-11-13). "Пошкоджена обстрілами бібліотека Короленка у Харкові збирає гроші на відновлення". Суспільне | Новини (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2025-02-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Будівля судових установлень – Харків, що манить". moniacs.kh.ua. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Особняк Бекетових-Алчевських | Харківська мапа". khuamap.netlify.app. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Особняк купця Соколова – Харків, що манить". moniacs.kh.ua. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Відлуння прекрасного – Харків, що манить". moniacs.kh.ua. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Будівля Державного банку | Харківська мапа". khuamap.netlify.app. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Будинок товариства робітників | Харківська мапа". khuamap.netlify.app. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Архітектор, який зробив Харківський вид - Бекетов Олексій Миколайович - kharkov-future.com.ua" (in Ukrainian). 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ Карнацевич В. 100 знаменитых харьковчан. — Харьков: Фолио, 2005. — 512 с. — 3000 экз. — ISBN 966-03-3202-5.

- ^ ngeorgij (10 April 2012). "Исчезнувшие ряды". Харьков: новое о знакомых местах. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Бекетов Алексей Николаевич — Днепровская городская энциклопедия". tfde.dp.ua. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

- ^ "Бекетівський Київ – Харків, що манить". moniacs.kh.ua. Retrieved 2025-02-26.

Sources

- Tsomyk, Hanna (17 November 2024). ""Харків спадковий". Алчевські-Бекетови — не знищений рід. Оповідь спадкоємиці" ["Kharkiv is hereditary." The Alchevski-Beketovs - an unextinct family. The story of an heiress]. Suspilne Kharkiv.

- Davydova, N.B.; Statkus, V.O.; Shanhei, O.M. (2023). Олексій Миколайович Бекетов: життя і творчість (1862–1941). Біобібліографічний покажчик (in Ukrainian). Kharkiv: Kharkiv National University of Urban Economy named after O. M. Beketov.

- Solodovnik, Vitalii (2 February 2023). "Історія відомої харківської персони" [The story of a famous Kharkiv person]. Я культурний.

Further reading

- "The 145th Anniversary of the Birth of A. N. Beketov" by Darya Dudushkina @ Архитектурный вестник (The Architectural Bulletin), 2007

- Detailed biography by L. Rozvadovskaya @ URA-Inform

- Biography by D. Petrenko @ Вечерний Харьков

- Biography and photographs by N. Khorobrykh @ Our Kharkhiv

External links

- Interview with Beketov's descendants on the website "Suspilʹne. Kharkiv"

- "Дом-Музей Академика Архитектуры А. Н. Бекетова" (The Beketov Museum) @ the Alushta website

- Monument to Beketov© at the University of Construction and Architecture

![Alexander Commercial School [uk] (1889–1901)](Https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4a/KhKU-building.jpg/180px-KhKU-building.jpg)

![Own house on Zhon-Myronosyts Street [uk] (1896–1897)](Https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7c/%D0%91%D1%83%D0%B4%D0%B8%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%BA_%D0%B2%D1%87%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B8%D1%85.%D0%A5%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%BA%D1%96%D0%B2.jpg/180px-%D0%91%D1%83%D0%B4%D0%B8%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%BA_%D0%B2%D1%87%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B8%D1%85.%D0%A5%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%BA%D1%96%D0%B2.jpg)

![P. V. Markov Merchant's Mansion (1901, Darwin Street [uk]);](Https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4d/Kharkiv%2C_Darvina%2C_23.jpg/158px-Kharkiv%2C_Darvina%2C_23.jpg)

![Building at 9 Hrushevskoho Street [uk], Kyiv](Https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e4/%D0%92%D1%83%D0%BB%D0%B8%D1%86%D1%8F_%D0%9C%D0%B8%D1%85%D0%B0%D0%B9%D0%BB%D0%B0_%D0%93%D1%80%D1%83%D1%88%D0%B5%D0%B2%D1%81%D1%8C%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BE_9_%D0%9A%D0%B8%D1%97%D0%B2_2013_01.JPG/180px-%D0%92%D1%83%D0%BB%D0%B8%D1%86%D1%8F_%D0%9C%D0%B8%D1%85%D0%B0%D0%B9%D0%BB%D0%B0_%D0%93%D1%80%D1%83%D1%88%D0%B5%D0%B2%D1%81%D1%8C%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BE_9_%D0%9A%D0%B8%D1%97%D0%B2_2013_01.JPG)

![Monument to Beketov [uk] in Kharkiv](Https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9f/%D0%9F%D0%B5%D0%BC%27%D1%8F%D1%82%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%BA_%D0%91%D0%B5%D0%BA%D0%B5%D1%82%D0%BE%D0%B2%D1%83.jpg/160px-%D0%9F%D0%B5%D0%BC%27%D1%8F%D1%82%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%BA_%D0%91%D0%B5%D0%BA%D0%B5%D1%82%D0%BE%D0%B2%D1%83.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.