Chester railway station is located in Newtown, Chester, England. It was designed by the architect Francis Thompson and opened as a joint station in 1848. From 1875 to 1969, the station was known as Chester General to distinguish it from Chester Northgate. The station is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a Grade II* listed building.[1]

A refurbishment was completed in 2007 that provided a new roof, improved customer facilities and improved access to the station.[2]

Services from Chester station are operated to London Euston, Cardiff Central, Holyhead, Liverpool Central, Manchester Piccadilly, Leeds, Wrexham General, Shrewsbury, Liverpool Lime Street, Manchester Airport, Crewe, Birmingham New Street, Birmingham International and Llandudno.

History

Names

Prior to 1848 there were two stations opposite each other across Brook Street, both known as Chester to their respective users.[3] They were superseded by a larger joint station that was also called Chester, although sometimes known as Chester Joint or Chester General.[a] The name of Chester General gradually came more into use from around 1870 to distinguish it from Chester Northgate prior to it opening in 1875, and then it reverted to simply Chester when Northgate closed in 1969.[3][5]

Early stations

The first station at Chester was opened on the northwest side of Brook Street by the Chester and Birkenhead Railway (C&BR) when it opened its line from Birkenhead Grange Lane on 23 September 1840.[6]

One week later, on 1 October 1840, the Grand Junction Railway (GJR) opened a separate station, on the southeastern side of Brook Street, opposite the C&BR station, when it opened its branch from Crewe.[7] This line and station had been planned and mostly constructed by the Chester and Crewe Railway (C&CR), but they ran out of capital before completing the line and were taken over by the GJR on 1 July 1840.[6]

Relations between the C&BR and the C&CR had been cordial and collaborative with joint projects being undertaken. The C&BR had arranged to rent offfices and other buildings from the C&CR, however the GJR had been hostile to the C&BR from the beginning, seeing them as competitors for traffic to Liverpool, and their takeover of the C&CR caused the joint plans to fall through.[6]

This resulted in the C&BR initially having no passenger accommodation at their station. In October 1840 their engineer reported that there "was a temporary wooden hut for a booking office but no passenger shed", six months later "he confessed that a wooden hut had been used for five months, but latterly some houses in Brook Street had been converted into an office and waiting room, a large shed and a landing stage (platform) had been provided for the convenience of passengers".[6][8]

The C&BR and the GJR lines were connected by a through line that avoided both stations but there were no through services, the two stations were connected across Brook Street but the connecting line was gated and there were no through services, not even for the Royal Mail, whose bags were carried over the road.[9][10][11]

To the southeast of Chester there were two railways that had been authorised in the same parliamentary session in 1844 that planned to use Chester as their terminus, one was the Chester and Holyhead Railway (C&HR) who started constructing a line along the North Wales coast on 1 March 1845.[12] The other was the Shrewsbury and Chester Railway (S&CR) constructing a line to Ruabon and Shrewsbury.[b][13] This line was planned to connect to the C&HR at Saltney junction and use the C&HR line for the final 1 mile 67 chains (3.0 km) into the C&BR station in Chester.[c][16]

Negotiations between these two railways started in November 1844 as the S&CR wanted to make sure that the C&HR section of line from Saltney junction into Chester would be open when they were ready to use it. Negotiations continued until May 1846 when it was estimated the section might be ready by October 1846. A minimum monthly toll of £2,000,(equivalent to £245,000 in 2023[d]) was agreed until the C&HR was finished.[17]

The S&CR took possession of the section and started running trains into Chester on 4 November 1846.[13] The C&HR retook possession of the Chester to Saltney section when it opened its own line as far as Bangor on 1 May 1848.[18] The C&HR was operated by the London and North Western Railway (L&NWR).[19]

The Birkenhead, Lancashire and Cheshire Junction Railway (BL&CJR) was incorporated on 26 June 1846 and authorised to construct a line from Chester to Walton junction near Warrington where it connected to the GJR. The same Act authorised the BL&CJR and the C&BR to amalgamate, retaining the Birkenhead, Lancashire and Cheshire Junction Railway name.[20]

In the meantime the GJR amalgamated with several others to become the L&NWR on 16 July 1846.[21]

Joint station 1848 to 1890

By 1845 there were four railway companies having or planning their lines terminate at Chester, and it became "apparent that the separate but adjoining stations would have to be replaced by something better"; a joint station was proposed.[e][24] A site was selected south of the existing stations and east of Brook Street, an area of simple fields and kitchen gardens with a little brooklet, spanned by a rustic bridge, with the odd-sounding name of Flookersbrook.[24][25]

In December 1846 the four project partners, the L&NWR, the C&HR, the S&CR and a joint partnership between the BL&CJR and the C&BR agreed to share the cost of the land and buildings and a joint committee of one director from each company was set up.[f][26] Additionally, on 9 July 1847 the Mold Railway was granted parliamentary authority to construct its line which joined the C&HR at Saltney Ferry junction and it intended to use Chester as its terminus.[27]

The station was authorised by two Acts, the Shrewsbury and Chester Railway Act 1847 and the Chester and Holyhead Railway (Chester Extension and Amendment) Act 1847, both Acts put in place the joint responsibility for building and altering access lines from the old stations to the new. Robert Stephenson was appointed as the engineer for the project. The station was designed by the architect Francis Thompson assisted by C. H. Wild, it was constructed by Thomas Brassey. The foundation stone was laid in August 1847.[26] The station was opened on 1 August 1848 having cost £55,000 (equivalent to £6,975,000 in 2023[d]).[28]

It was designed with one very long platform, chiefly for departing trains, with two long bay platforms at each end and three shorter ones for terminating trains, the whole covered by a roof supported by cast iron columns designed by C.H.Wild.[28][29][30] On the other side of the through tracks was "a large carriage shed with an iron and glass roof and beyond that a goods shed".[28] A useful sketch of the station layout is in Biddle (1986) and Maund (2000).[31][32]

The long single platform was used for trains running in opposite directions and had a scissor or crossover junctions installed in the middle to enable two trains to occupy it and leave in either direction.[31] This made the station very long and Thompson designed "a highly ornamental Venetian-style façade 1,050 feet (320 m) long in dark red brick with generously applied stone dressings and sculptured decoration by John Thomas.[g][29][33]

There was a central fifteen bay two-story entrance and office building, containing 50 rooms and offices, flanked by five bay projecting taller ornate, turreted, balconied sections, the whole extended in both directions by arcaded screen walls terminating in lower towers.[28][29] Windows in the central range are adorned with pediment carvings, described by Jenkins (2017) as Hindu in character.[34] Pedestrian access was protected by an entrance canopy with decorative ironwork.[35]

The interior of the station had the principal passenger accommodation done in wood and plasterwork.[33] The refreshment rooms were better decorated than the waiting rooms having more elaborate plasterwork, decorated woodwork and a fine coffered ceiling.[36][37] The refreshment room was run by Mr Hobday who paid the joint station committee £500 per year for the right (equivalent to £66,000 in 2023[d]).[4][8]

The Goods Station, a substantial red and blue brick building, consisting of a shed 180 feet (55 m) long and 120 feet (37 m) wide, with four railway and two cart entrances, at either end, and one railway entrance in front. It is covered by two large roofs, supported down the centre of the building by cast-iron columns and girders, and lighted by two skylights.[38] To the west of the station there was a triangular junction which allowed some trains to by-pass the station and was used to turn locomotives.[28]

Brook Street needed to be moved to accommodate the station, at the same time it was converted into a bridge over the station approach tracks. The bridge is of brick and stone, consisting of six girder and fifteen brick arches; the latter of which were converted into stabling.[6][38][39]

There was long standing rivalry between the L&NWR and the GWR over access to the area, in particular to Birkenhead and Liverpool. This came to a head at Chester in 1849, the L&NWR was the most powerful of the joint committee partners and it had considerable influence over the C&HR whose trains it operated, and some influence over the BL&CJR who had so far not objected to the L&NWR's actions.[40] The L&NWR ranged itself against the S&CR and its new partner the Shrewsbury and Birmingham Railway (S&BR) which opened a line from Shrewsbury to a temporary station at Wolverhampton on 12 November 1849. These two companies were a possible threat to the L&NWR by letting the GWR into the area.[40]

After one quarrel over the routeing of passengers, the L&NWR refused to allow passengers to be booked to Wolverhampton or beyond via Shrewsbury, which was a sensible way to go but competed with the L&NWR route via Crewe; the L&NWR had the S&CR booking clerk forcibly ejected from his office. Connections with S&CR trains were deliberately timed to create inconvenience, and when the S&CR ran horse buses for the convenience of its passengers they found them barred from the station forecourt.[33][41][42]

The Mold Railway opened on 14 August 1849, it ran two services daily into Chester, it was operated by the L&NWR.[43][44] The C&HR main line was connected throughout on 18 March 1850 and trains, operated by the L&NWR, started running through to Holyhead.[45][46]

On 18 December 1850 the BL&CJR opened a line from Chester to Walton junction, near Warrington, where it connected to the L&NWR railway running from Crewe to Warrington Bank Quay, now part of the West Coast Main Line.[24][47]

In January 1851 the S&CR and the S&BR entered into a mutual running agreement with the GWR and on 7 August 1854 they became part of the GWR.[28][48]

In 1858 the C&HR agreed to amalgamation with the L&NWR, this took effect on 1 January 1859 and included the Mold Railway.[49]

In 1859 the BL&CJR changed its name to the Birkenhead Railway (BR).[50] In 1860 it came to an arrangement with the L&NWR and the GWR jointly for them to work their railway. A joint committee was formed to do so, this was formalised by parliament in 1861.[h][50]

The committee decided to improve road access to the station believing the approach by way of Brook Street was inadequate. The station needed a more direct access from Foregate Street. Unfortunately the committee had no power to purchase properties for the purposes of road construction or improvement but it did have some land in front of the station which it could utilise. Negotiations started in 1857 and in 1860 the Queen Hotel opened opposite the station and connected to it via a covered passage, by 1866 the buildings which obstructed a better road access had been purchased and demolished and City Road, a wide, almost straight approach road was opened, unfortunately the Queen Hotel blocked the view of the station clock, manufactured by J. B. Joyce & Co, from the new City Road above the station entrance and the clock was moved to an off-centre location closer to the left towered section.[8][52][53]

A report in 1861 shows the station having a throughput of 2 million passengers using an average of 115 trains daily. This level of traffic was catered for by 58 departing and 57 arriving trains. 44 of the arriving trains were divided and re-formed into new trains, this work being done by two horses kept for the purpose. The station had 1 stationmaster, 1 inspector, 10 clerks, 6 ticket collectors and examiners, 32 porters (including 4 foremen), and assorted greasers, police, watchmen, carriage examiners, shunters, waiting room attendants, cleaners and lamp men, a total of 82. There were 10 more in the parcels office and 138 in the goods department, who dealt with an average of 130 daily goods trains.[54]

A change of committee occurred in 1867. The L&NWR and the GWR had at the time eight joint committees including the BR and the Chester Joint Station Committee; all eight were merged into a L&NW & GW Railway Joint Committee. The change did not affect the workings of the individual concerns except the line from Chester Joint station eastwards to where the line to Walton junction branched off, about 24 chains (1,600 ft; 480 m) was now considered part of the BR (see the junction diagram).[55]

On 1 May 1875, Chester Northgate railway station was opened by the Cheshire Lines Committee (CLC), to reduce confusion between the stations, this station, the older one was renamed Chester General although it had been frequently known by this name since opening in 1848.[3][4][56][57]

In 1875 and 1885 there was a joint booking office by the station entrance,[39][32], by 1905 each of the companies had their own booking office, L&NWR to the right as you entered and the GWR to the left.[58]

From March 1876 Chester station introduced a luncheon basket service for passengers on the Irish Mail, the first in the country, described by Neele in 1904 as either aristocratic or democratic, depending on the contents, and cost.[59]

Extended joint station since 1890

In 1890 a new island platform was added and eight through lines provided, there were five bays at the Crewe end and three at the Holyhead. Additional buildings, extended roofing, two new footbridges and hydraulic luggage lifts completed the improvements.[37][60]

The goods station had to be relocated to create the space to achieve this and it was moved further away from the passenger station, adjacent to Lightfoot Street, at the same time it became single sided with access from the Crewe end. The new warehouse opened on 7 January 1889, it had six lines running into the shed and five sidings outside. This shed and its yard were the L&NWR goods facility for the station; it was equipped with a 10-ton crane. The GWR goods facilities consisted of a shed and yard on the other side of, and accessed from, Brook Street, the access road sloping down past the cattle pens along the line towards Mollington, it was also equipped with a 10-ton crane.[61][62][63]

The grouping had little effect on the station, whose owners went from being the L&NWR and the GWR to being the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS) and the GWR.[64]

The station was renovated between 1955 and 1961 with new platform coverings, track circuiting, and colour-light signals.[65]

Chester Northgate station was scheduled for closure on 6 October 1969. Before closing a level junction was installed at Mickle Trafford so trains from Manchester could run directly into Chester General; the junction had been removed in 1875.[66]

On 7 November 2005 a plaque commemorating Thomas Brassey was installed on the wall opposite the booking office.[67] Brassey was born at Buerton 6 miles (9.7 km) south of Chester.[68]

A refurbish and improvement project started in 2005, the Chester Renaissance Project, under this project

- Network Rail did some groundworks around the east end frontage, repairs to the façade's east and west wings, renewed some of the roof's glazing and made enhancements to the train shed.[2]

- Local traffic management was improved and better access to the station was achieved by alterations to Station Square which were completed in December 2007.[2]

- A new travel centre with improved customer facilities, refurbished toilets, café units and architectural lighting was installed by Arriva Trains Wales in October 2008.[2]

- The wrought iron lattice girder footbridge originally provided in 1848 was refurbished and opened on 6 June 2013.[69]

Service history

Local GWR trains operated to Ruabon, Shrewsbury and Wrexham General.[70] Chester was served by most GWR express passenger trains, the service started on 1 May 1857, running from London Paddington initially to Birkenhead Monks Ferry, [71] and then to Birkenhead Woodside after it opened in 1878. In 1880 a fast train was introduced, taking 4 hours and 50 minutes, more than an hour faster than previously from London, the return train was not quite so fast taking 5 hours and 20 minutes, by 1912 the fastest service took 4 hours 15 minutes, there were normally six trains daily.[72]

The GWR introduced other long-distance services from time to time, often just during the summer, in July 1922 there were through trains to Leamington Spa, Dover Marine, Pwllheli, Southampton Town, Bournemouth[i], Aberystwyth and through carriages to Barmouth.[70]

Calling at Chester involved a reversal of train direction for GWR trains and therefore the fastest services used the curve to avoid the station, some years the Chester portion of the Birkenhead train was detached at Wrexham, it had even been known for the Chester portion to be detached in the cutting west of the station.[73] The final service from Paddington ran on 4 March 1967, specially named The Zulu, it was hauled by 7029 Clun Castle from Banbury to Birkenhead.[75]

Local L&NWR trains ran to Crewe, Stafford, Whitchurch, Corwen, Liverpool Lime Street and Manchester Exchange.[76]

Through fares to London were available by 1847. The local newspaper advertisement indicated that the service was on a single train, but Bradshaw (1847) suggests that a change of trains would be needed at Birmingham.[22][77] By 1850 trains were running through; there were six services, with four continuing to Bangor.[78]

The L&NWR service to and from London Euston was taking around 4 hours and there were an average of fourteen daily trains in 1922, eight of which, including the twice daily Irish Mails, continued to Holyhead. There were also a couple of services going to Holyhead that ran through Chester without stopping.[79]

The joint lines of the BR were worked by both companies, the L&NWR and the GWR which led to some GWR locomotives taking trains from Chester to Manchester Exchange.[80]

Regular L&NWR services to Liverpool Lime Street via the Halton Curve were withdrawn on 5 May 1975, line usage being reduced to a scheduled "parliamentary" summer Saturdays-only return service between Liverpool Lime Street and Chester.[81][82]

In 1987 the station had nearly 120 departures each weekday with local diesel multiple unit services to Hooton, Helsby, Manchester via Northwich and Warrington and Wrexham. Main-line services were still locomotive hauled and there were boat-trains and early morning newspaper trains from Manchester.[83]

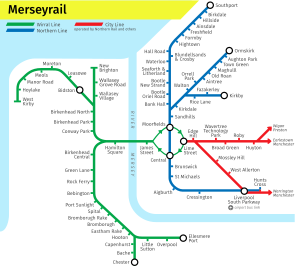

On 3 September 1993 Merseyrail extended and electrified, using the 750 volt DC third rail system, the Wirral Line line from Hooton into Chester station. The line provided an every 15 minute peak and an every 30 minutes off-peak service to Birkenhead and Liverpool.[84] The extension uses Platform 7, the only one that has been electrified.[85]

The Halton Curve services restarted running in May 2019,[86] providing Chester with a direct link to Liverpool Airport via Liverpool South Parkway and an alternative route to Liverpool city centre with trains running to Liverpool Lime Street.[87]

In January 2016, according to the Office of Rail and Road, passenger numbers doubled over the previous ten years, making Chester the eighth-busiest station in the North-West region. The rise was attributed to new services, such as direct trains to London and increased frequencies on the Merseyrail network.[88]

Excursion traffic

Chester has generally been a desirable destination for excursion traffic. In "1857 up to a third of a million excursion passengers reportedly passed through Chester station during the second half-year, around 12,000 a week" it was further "reported in 1858 that over 52,000 excursionists visited Chester by rail in Whit week".[89] The three day race meeting in May is the busiest time of the year, cup day being the most popular. As early as 1848 the stations had to cope with despatching 426 carriages in the hours after the meeting.[90] In 1905 the station staff dealt with 358 arrivals and departures over thirteen hours, a crowded train every two minutes.[91]

There were also excursions from Chester, when Brunel's SS Great Eastern was at Holyhead in October 1859 as many as fifteen excursion trains a day were organised from Chester to visit it.[92]

Stationmasters

When the station was constructed an octagonal office with a pagoda roof was constructed in its centre for the stationmaster.[37] From the opening of the joint station the management committee decided the stationmaster should be 'neutral', that is not recruited from any of the participant companies.[93]

- William Paget ca. 1847

- Mr. Jones ca. 1849

- John Critchley ca. 1850–1855[56] (afterwards superintendent of the Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton Railway)

- Charles Mills ca. 1859–1872[57]

- David Meldrum 1872–1882[94]

- W. Thorne 1882[95]–1890 (formerly station master at Hereford Barrs Court)

- John Thomas Reddish 1890–1902[96]

- W.G. Marrs 1903–1909[97]

- John Ratcliffe 1910[98]–1926

- Robert McNaught 1926[99]–1932

- Lewis Evans 1932[100] 1934

- A.E. Mawson 1934[101]–1942 (formerly station master at Woodside)

- John Moore 1943–1950 (formerly station master at Birkenhead Dock)

- Percy Jackson 1950[102]–1955

- Eric L Thompson 1955[103]–1963 (formerly station master at Bedford)

- Kenneth Conyers Winterton 1963–1964[104]

- Mr. Mapstone ca. 1967 ca. 1969

Accidents

- On 4 July 1949, a Derby to Llandudno passenger train ran into the rear of a Crewe to Holyhead passenger service, injuring fifty people.[105]

- Chester General rail crash. On 8 May 1972, a freight train suffered a brake failure and collided with a diesel multiple unit at Chester General station and caught fire, causing severe damage to the building and the trains involved.[106] The portion of the overall station roof between Platforms 5/6 and the main building which had been damaged by the collision and fire had to be removed.

- On 20 November 2013, a Class 221 Super Voyager diesel-electric multiple unit from London Euston to Chester collided with the buffer stops on platform 1, riding up over them and smashing a glass screen. There were no injuries, although one passenger was taken to hospital for checks. A Rail Accident Investigation Branch report stated that the incident was due to exceptionally slippery rails, but that the consequences of this were made more severe by the buffer stop being of an older design which did not absorb the impact energy effectively. The report further stated that that particular stop had not undergone a risk assessment within the previous ten years, and was possibly not appropriate for class 221 units.[107][108]

Current station

Facilities

The station has a travel centre (booking office) that is staffed from 15 minutes before the first train until 15 minutes after the last train. There are live departure and arrival screens, a shop and a cafe. The station has lifts and is fully accessible for disabled users. It has a car park with 83 spaces and cycle racks for 68 cycles.[109][110]

Layout

The station has seven platforms.

- Platform 1 is a bay platform located at the east end (a second platform alongside it is unused but may be used for stock stabling).

- Platform 2 at the western end is another bay platform.

- Platform 3 is a through bi-directional platform and is closest to the concourse; it is split into sections 'a' (eastern) and 'b' (western), although on occasions a train will use the middle of the platform.

- Platform 4, (opposite Platform 3 on the island platform) is another through bi-directional platform, with sections designated as 4a and 4b.

- Platform 5 is an east facing bays in the centre of the island, closest to platform 4.

- Platform 6 is another east facing bay behind platform 5 and closest to platform 7.

- Platform 7 is a through platform, the only one with third-rail electrification, with sections designated as 7a and 7b.[111]

Services: winter 2024/2025

Details extracted from the winter 2024/2025 timetables showing the Monday to Friday daytime service in trains per hour (tph) or trains per day (tpd), only the departing services are shown, there is a corresponding number of arrivals.[j]

Transport for Wales

- 1 tph to Crewe usually departs from platform 1.[113]

- 1 tph to Wrexham General and Shrewsbury of which alternate trains continue to Cardiff Central and Birmingham International usually departs from platform 3 or 4.[114]

- 1 tph to Holyhead, via Bangor usually departs from platforms 2, 3 or 4.[115]

- 1 tph to Llandudno, via Llandudno Junction usually departs from platform 3 or 4.[113]

- 1 tph to Liverpool Lime Street, via Runcorn, using the Halton Curve usually departs from platform 5.[113]

- 1 tph to Manchester Airport, via Warrington Bank Quay and Manchester Piccadilly usually departs from platform 3 or 4.[113]

- 3 tpd to Wrexham General, very early, evening and late, usually departs from platform 4.[114]

- 3 tpd to Shrewsbury, early, evening and very late, usually departs from platform 4.[114]

Avanti West Coast

- 1 tph to London Euston via Crewe with most services also calling at Stafford usually departs from platform 3 or 4.[116]

- 6 tpd to Bangor and Holyhead, mostly early and late in the day.[116]

- 1 tpd to Wrexham General usually departs from platform 3 or 4.[116]

Northern Trains

- 1 tph on the Mid-Cheshire Line to Stockport and Manchester Piccadilly, via Northwich, a two-hourly service operates on Sundays.[117]

- 1 tph to Leeds via Warrington Bank Quay, Manchester Victoria and Bradford Interchange.[118]

Merseyrail

- 4 tph to Liverpool Central via Birkenhead. On late evenings and Sundays, the frequency is every 30 minutes.[119] Merseyrail services to Birkenhead and Liverpool use platform 7b or 7a; platform 7 is the only third-rail equipped platform.[85] These services are provided by Class 777 EMUs.[citation needed]

Table of services

Railway lines in Chester | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

-

The east end of Chester General Station on a Summer Saturday in 1962.

-

Distance board found in some disrepair on a station wall

-

Platform 1, used by trains to Crewe

See also

Notes

- ^ For example, an advertisement for the refreshment rooms in 1849 uses the name General,[4]

- ^ The S&CR was formed by an amalgamation of the North Wales Mineral Railway (NWMR) and the Shrewsbury, Oswestry and Chester Railway (SO&CR) on 27 July 1846.[13]

- ^ Railways in the United Kingdom are, for historical reasons, measured in miles and chains[14]. A chain is 22 yards (20 m) long, there are 80 chains to the mile.[15]

- ^ a b c UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017), "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)", MeasuringWorth, retrieved 7 May 2024

- ^ Traffic levels were increasing creating pressure for better facilities, for example weekdays in August 1847 had 9 arrivals and departures from the L&NWR Brook Street station, whilst the BL&CJR Brook Street station had 19, 12 for themselves and 7 for the S&CR.[22] Weekdays in May 1848 had 9 arrivals and departures from the L&NWR Brook Street station, whilst the BL&CJR Brook Street station had 24, 12 for themselves, 8 for the S&CR and 4 for the C&HR.[23]

- ^ Above it was noted that the BL&CJR and the C&BR had amalgamated in June 1846, there was however some legal difficulties that had not been resolved, both companies were therefore included by name in the Acts.[20]

- ^ There is some dispute over the colour of the bricks used, Biddle (2003) says they are dark red, although earlier in his Railway Heritage co-authoured with Nock (1990) he describes tham as buff coloured, Pevsner (2011) says they are Staffordshire blue, Jenkins (2017) has them as Purple-pink, they are recorded in the National Heritage list as pale brown.[1][29][33][34][30]

- ^ An Act for vesting the Birkenhead Railway in the London and North-western Railway Company and the Great Western Railway Company, and for other Purposes.[51]

- ^ The weekdays daily train to Southampton Town and Bournemouth had started from Manchester London Road and got to Chester via Birkenhead Woodside, it replaced a through carriage service that had started in 1903.[73][74]

- ^ The platform for a service has been extracted from the online National Rail Enquiries and is subject to changes at short notice, some services go from different platforms on different days.[112]

References

- ^ a b Historic England. "Chester railway station (1375937)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ^ a b c d "The Renaissance Projects". The Chester Renaissance. Archived from the original on 21 August 2008. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- ^ a b c Quick 2023, p. 130.

- ^ a b c "Chester General Station Refreshment Rooms". Liverpool Albion. England. 30 April 1849. p. 1. Retrieved 1 March 2025 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Slater 1974, p. 361.

- ^ a b c d e Maund 2000, p. 9.

- ^ Webster 1972, p. 115.

- ^ a b c Hewitt 1972, p. 30.

- ^ "Opening of the Chester and Birkenhead Railway". Chester Courant. 29 September 1840. p. 3. Retrieved 18 February 2025 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Whishaw 2016, p. 56.

- ^ Holt & Biddle 1986, p. 46.

- ^ Baughan 1972, p. 60.

- ^ a b c MacDermot & Clinker 1964a, p. 178.

- ^ Jacobs 2009, p. 11.

- ^ "Weights and Measures Act 1985". Legislation.gov.uk. Sch 1, Part VI. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ Gardner 1938, p. 182.

- ^ Baughan 1972, p. 70.

- ^ Baughan 1972, p. 296.

- ^ Baughan 1972, p. 82.

- ^ a b Maund 2000, p. 19.

- ^ Reed 1996, p. 3.

- ^ a b "Railway Departures and Arrivals". Chester Courant. England. 11 August 1847. p. 1. Retrieved 21 February 2025 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Railway Departures and Arrivals". Chester Courant. England. 17 May 1848. p. 4. Retrieved 21 February 2025 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b c Maund 2000, p. 20.

- ^ Audsley 1908, p. 25.

- ^ a b Maund 2000, pp. 20–21.

- ^ "The Mold Railway, (from Mold, to Join the Chester and Holyhead Railway, with powers of Sale or Lease to the Chester and Holyhead Company.)". Chester Chronicle. England. 13 November 1846. p. 2. Retrieved 1 March 2025 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b c d e f Maund 2000, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d Biddle 2003, p. 463.

- ^ a b Hartwell et al. 2011, p. 249.

- ^ a b Biddle 1986, p. 80.

- ^ a b Maund 2000, p. 36.

- ^ a b c d Biddle & Nock 1990, p. 96.

- ^ a b Jenkins 2017, p. 213.

- ^ Body 1990, p. No page numbers, alphabetical entries.

- ^ Biddle 1986, p. 93.

- ^ a b c Biddle 2003, p. 464.

- ^ a b Parry 1849, p. 24.

- ^ a b Chester - Cheshire XXXVIII.11.9 (Map). 1:500. Ordnance Survey. 1875.

- ^ a b Biddle 1986, p. 31.

- ^ MacDermot & Clinker 1964a, p. 184.

- ^ Jenkins 2017, p. 212.

- ^ Baughan 1980, p. 50.

- ^ "Railway Departures and Arrivals". Chester Courant. England. 22 August 1849. p. 4. Retrieved 1 March 2025 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Gardner 1938, p. 183.

- ^ Baughan 1972, p. 135.

- ^ Biddle 1997, p. 559.

- ^ Grant 2017, pp. 502–503.

- ^ Baughan 1972, pp. 177–178.

- ^ a b Maund 2000, p. 27.

- ^ "Birkenhead Railway (Vesting) Act 1861", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 11 July 1861, c.,

24 & 25 Vict. c. cxxxiv

- ^ Audsley 1908, p. 27.

- ^ Bethell 2006, p. 82.

- ^ Maund 2000, p. 89.

- ^ Maund 2000, p. 34.

- ^ a b "Mr. Critchley's Testimonial". Chester Courant. England. 24 January 1855. Retrieved 22 August 2021 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b "Railway news". Eastern Morning News. England. 16 September 1872. Retrieved 22 August 2021 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Lawrence 1905, p. 178.

- ^ Neele 2022, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Baughan 1980, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Maund 2000, pp. 42 & 65.

- ^ Cheshire XXXVIII.11 (Map). 25 inch. Ordnance Survey. 1899.

- ^ The Railway Clearing House 1970, p. 118.

- ^ Maund 2000, p. 51.

- ^ Baughan 1980, p. 32.

- ^ "Notes and News: Junction of 1875 to be re-instated". Railway Magazine. Vol. 115, no. 816. April 1969. p. 225.

- ^ "Thomas Brassey commemorated at Chester". Railway Magazine. Vol. 152, no. 1257. January 2006. p. 84.

- ^ Helps 2006, p. 25.

- ^ "Chester footbridge refurbished". Railway Magazine. Vol. 159, no. 1349. September 2013. p. 89.

- ^ a b Bradshaw 1985, tables 87–89.

- ^ MacDermot & Clinker 1964a, p. 215.

- ^ MacDermot & Clinker 1964b, pp. 248–249 & 259.

- ^ a b Maund 2000, p. 65.

- ^ Bradshaw 1985, tables 81, 87, 88, 127, 135, 459 & 480.

- ^ Hendry & Hendry 1992, p. 116.

- ^ Bradshaw 1985, tables 389, 450, 462, 464, 470 & 474.

- ^ Bradshaw 1847, p. 27.

- ^ Bradshaw 2012, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Bradshaw 1985, tables 464–466.

- ^ Holt & Biddle 1986, pp. 260–261.

- ^ "Train service withdrawal". Railway World. No. 420. April 1975. p. 138.

- ^ Chatterton, Mark (April 2011). "Ghost trains and eerie stations: Frodsham to Runcorn". Railway Magazine. Vol. 157, no. 1320. p. 42.

- ^ a b Roughly 1987, p. 501.

- ^ "Hooton-Chester line goes 'live'". Railway Magazine. Vol. 139, no. 1111. November 1993. p. 70.

- ^ a b Bridge 2013, p. 35.

- ^ "Halton Curve: Rail line links north Wales and Liverpool". 19 May 2019.

- ^ "New Chester to Liverpool rail service - more details released". 3 April 2019.

- ^ Holmes, David (29 January 2016). "Chester Railway Station sees passenger numbers double in 10 years". Chester Chronicle.

- ^ Major 2015, p. 19.

- ^ "Chester Spring Meeting". Chester Courant. England. 10 May 1848. Retrieved 8 March 2025 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Lawrence 1905, p. 183.

- ^ Major 2015, p. 9.

- ^ Hewitt 1972, p. 32.

- ^ "Railway Appointment". Chester Courant. England. 6 September 1882. Retrieved 22 August 2021 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Mr. W. Thorne". Hereford Times. England. 30 September 1882. Retrieved 21 August 2021 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Death of Mr. T.J. Reddish, Prestatyn". Flintshire County Herald. England. 20 May 1921. Retrieved 21 August 2021 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Mr. Marrs Retirement". Cheshire Observer. England. 2 April 1910. Retrieved 21 August 2021 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "New Stationmaster at Chester". Shrewsbury Chronicle. England. 7 January 1910. Retrieved 21 August 2021 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Chester's New Stationmaster". Crewe Chronicle. England. 4 December 1926. Retrieved 21 August 2021 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "New Chester Stationmaster". Liverpool Echo. England. 13 June 1932. Retrieved 21 August 2021 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Local Notes". Cheshire Observer. England. 14 April 1934. Retrieved 21 August 2021 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Chester's Stationmaster". Liverpool Echo. England. 6 October 1950. Retrieved 21 August 2021 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Chester Stationmaster". Liverpool Echo. England. 4 November 1955. Retrieved 21 August 2021 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Last man to wear top hat at station". Crewe Chronicle. England. 30 December 1971. Retrieved 21 August 2021 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Report on the Collision which occurred on 4th July, 1949, at Chester Station in the London Midland Region British Railways" (PDF). Railways Archive. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ "Report on the Derailment and consequent Fire on 8th May 1972 at Chester General Station in the London Midland Region British Railways" (PDF). Railways Archive. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ "Train crashes into Chester Station barrier". BBC News Online. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ "Buffer stop collision at Chester station 20 November 2013" (PDF). Rail Accident Investigation Branch. November 2014. pp. 5, 9, 29–30, 37. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ^ "Stations: Chester". www.merseyrail.org. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ^ "Chester (CTR)". National Rail. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ^ "Chester station map". National Rail. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ^ "Chester: Live Departures and Arrivals". National Rail Enquiries. Retrieved 3 March 2025.

- ^ a b c d "Train times Holyhead - Llandudno - Chester - Manchester, 15 December 2024 - 17 May 2025" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 February 2025. Retrieved 3 March 2025.

- ^ a b c "Train times Chester - Birmingham, 15 December 2024 - 17 May 2025" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 December 2024. Retrieved 3 March 2025.

- ^ "Train times Holyhead - Cardiff Central (summary), 15 December 2024 - 17 May 2025" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 December 2024. Retrieved 3 March 2025.

- ^ a b c "Train Times for all Avanti West Coast routes to and from London Euston, 15 December 2024 to 17 May 2025" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 January 2025. Retrieved 3 March 2025.

- ^ "Manchester to Chester via Altrincham (Mid Cheshire Line) 17: train times 15 December 2024 – 17 May 2025" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2024. Retrieved 3 March 2025.

- ^ "Chester to Leeds 37: train times 15 December 2024 – 17 May 2025" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2025. Retrieved 3 March 2025.

- ^ "Train times Wirral Line Valid from 3 February until 17 May 2025" (PDF). Merseyrail. Retrieved 3 March 2025.

Bibliography

- Audsley, George Ashdown (1908). The Stranger's Handbook to Chester, Eaton Hall, Hawarden Castles, and vicinity. Chester: Phillipson and Golder.

- Baughan, Peter E. (1972). The Chester & Holyhead Railway. Newton Abbot: David and Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-5617-3. OCLC 641070.

- Baughan, Peter. E. (1980). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain. Vol. 11 North and Mid Wales. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7850-3.

- Bethell, David (2006). A portrait of Chester. Tiverton: Halsgrove. OCLC 1194919222.

- Biddle, Gordon (1986). Great Railway Stations of Britain: Their architecture, growth and development. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-8263-9.

- Biddle, Gordon; Nock, O. S. (1990). Railway Heritage of Britain: 150 years of railway architecture and engineering. London: Studio editions. ISBN 1-85170-595-3.

- Biddle, Gordon (1997). "West Coast Main Line (WCML)". In Simmons, Jack; Biddle, Gordon (eds.). The Oxford Companion to British Railway History From 1603 to the 1990s (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 559–560. ISBN 0-19-211697-5.

- Biddle, Gordon (2003). Britain's Historic Railway Buildings: An Oxford Gazeteer of Structures and Sites. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198662471.

- Body, Geoffrey (1990). Railway Stations of Britain : A guide to 75 important centres. Patrick Stephens. ISBN 978-1-85260-171-3.

- Bradshaw, George (1 March 1847). Bradshaw's Monthly Railway and Steam Navigation Guide for Great Britain, Ireland and the Continent. London: Bradshaw's General Railway Publication Office.

- Bradshaw, George (2012) [March 1850]. Bradshaw's Rail Times for Great Britain and Ireland March 1850: A reprint of the classic timetable complete with period advertisements and shipping connections to all parts. Midhurst: Middleton Press. ISBN 9781908174130.

- Bradshaw, George (1985) [July 1922]. Bradshaw's General Railway and Steam Navigation guide for Great Britain and Ireland: A reprint of the July 1922 issue. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-8708-5. OCLC 12500436.

- Bridge, Mike, ed. (2013). Railway Track Diagrams Book 4:Midlands & North West. Bradford on Avon: Trackmaps. ISBN 978-0-9549866-7-4.

- Gardner, E.H.W. (September 1938). "The Chester & Holyhead Railway - 1". Railway Magazine. Vol. 83, no. 495. pp. 181–188.

- Grant, Donald J. (2017). Directory of the Railway Companies of Great Britain (1st ed.). Kibworth Beauchamp, Leicestershire: Troubador Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-78803-768-6.

- Hartwell, Clare; Hyde, Matthew; Hubbard, Edward; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2011) [1971]. Cheshire. The Buildings of England. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-17043-6.

- Helps, Arthur (2006) [1872]. The life & labours of Thomas Brassey (1894 ed.). Stroud: Nonsuch. ISBN 1-84588-011-0.

- Hendry, R. Preston; Hendry, R. Powell (1992). Paddington to the Mersey. Oxford Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-86093-442-4.

- Hewitt, H.J. (1972). The Building of Railways in Cheshire Down to 1860. E. J. Morten. ISBN 978-0-901598-43-1.

- Holt, Geoffrey O.; Biddle, Gordon (1986). The North West. A Regional history of the railways of Great Britain. Vol. 10 (2nd ed.). David St. John Thomas. ISBN 978-0-946537-34-1. OCLC 643506870.

- Jacobs, Gerald (2009). "Railway Mileages". In Bridge, Mike (ed.). TRACKatlas of Mainland Britain. Bradford on Avon: Trackmaps. ISBN 978-0-9549866-5-0.

- Jenkins, Simon (2017). Britain's 100 Best Railway Stations. Viking. ISBN 978-0-241-97898-6.

- Lawrence, J.T. (September 1905). "Notable Railway Stations: No.33 The Chester General Station". Railway Magazine. Vol. 17, no. 99. pp. 177–183.

- MacDermot, E.T.; Clinker, C.R. (1964a) [1927]. History of the Great Western Railway, Volume I: 1833–1863 (First revised ed.). London: Ian Allan.

- MacDermot, E.T.; Clinker, C.R. (1964b) [1931]. History of the Great Western Railway, volume II: 1863–1921 (First revised ed.). London: Ian Allan.

- Major, Susan (2015). Early Victorian Railway Excursion: the Million go Fourth. Pen and Sword History. ISBN 978-1-4738-3528-3.

- Maund, T. B. (2000). The Birkenhead railway : (LMS & GW joint). Sawtry, Huntingdon: Railway Correspondence and Travel Society. ISBN 978-0-901115-87-4. OCLC 49815012.

- Neele, George P. (2022) [1904]. Railway Reminiscences: Late Superintendent of the line of the London and North Western Railway (Classic reprint ed.). London: Forgotten books. ISBN 978-1-332-03078-1. OCLC 1360265899.

- Parry, Edward (1849). The railway companion from Chester to Holyhead ... to which is added the tourist's guide to Dublin and its environs. Chester [England]: T. Catherall. OCLC 7896287.

- Quick, Michael (2023) [2001]. Railway passenger stations in Great Britain: a chronology (PDF). version 5.05. Railway & Canal Historical Society.

- The Railway Clearing House (1970) [1904]. The Railway Clearing House Handbook of Railway Stations 1904 (1970 D&C Reprint ed.). Newton Abbot: David & Charles Reprints. ISBN 0-7153-5120-6.

- Reed, Malcolm C. (1996). The London & North Western Railway: A History. Atlantic Transport. ISBN 978-0-906899-66-3.

- Roughly, Malcolm (August 1987). "Spotlight Chester". Railway Magazine. Vol. 133, no. 1036. pp. 499–501.

- Slater, J.N., ed. (July 1974). "Notes and News: Western's last "General"". Railway Magazine. Vol. 120, no. 879. London: IPC Transport Press Ltd. p. 361. ISSN 0033-8923.

- Webster, Norman W. (1972). Britain's First Trunk Line:The Grand Junction Railway. Adams & Dart. SBN 239 00105 2.

- Whishaw, Francis (2016) [1842]. The Railways of Great Britain and Ireland practically described and illustrated. Classic reprint series (2nd ed.). Forgotten Books. ISBN 978-1-334-18025-5.

Further reading

- Biddle, Gordon (1981). "Chapter 1 – North Cheshire & The Peak". Railway Stations in the North West. Clapham, Yorkshire: Dalesman. p. 8, fig. 1. ISBN 0-85206-644-9. – photo of station frontage

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (2010). Shrewsbury to Chester. West Sussex: Middleton Press. figs. 112-117. ISBN 9781906008703. OCLC 495274299.

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (2011). Chester to Rhyl. West Sussex: Middleton Press. figs. 1-6. ISBN 9781906008932. OCLC 795178960.

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (2012). Chester to Birkenhead. West Sussex: Middleton Press. figs. 1-8. ISBN 9781908174215. OCLC 811323335.

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (2012). Stafford to Chester. West Sussex: Middleton Press. figs. 102-120. ISBN 9781908174345. OCLC 830024480.

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (2013). Chester to Warrington. West Sussex: Middleton Press. figs. 1-5. ISBN 9781908174406. OCLC 910526793.

External links

- Train times and station information for Chester railway station from National Rail

- Station information for Chester railway station from Merseyrail

- "Chester to Shrewsbury Rail Partnership". Archived from the original on 21 October 2009.

- ORR Station Usage Estimates

![Carved wooden owl above Platform 4 at Chester Railway station intended to scare away pigeons, apparently declared unsuccessful in 1987.[83]](Https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/83/Chester_station_owl.jpg/88px-Chester_station_owl.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.