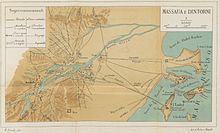

Massawa or Mitsiwa (/məˈsɑːwə/ mə-SAH-wə)[a] is a port city in the Northern Red Sea region of Eritrea, located on the Red Sea at the northern end of the Gulf of Zula beside the Dahlak Archipelago.[2] It has been a historically important port for many centuries. Massawa has been ruled or occupied by a succession of polities during its history, including the Dahlak Sultanate, the Ethiopian Empire, the Ottoman Empire and the Kingdom of Italy.

Massawa was the capital of the Italian Colony of Eritrea until the seat of the colonial government was moved to Asmara in 1897.[3]

Massawa has an average temperature of nearly 30 °C (86.0 °F), which is one of the highest experienced in the world, and is "one of the hottest marine coastal areas in the world."[4]

History

The historical Massawa lies on the islands Basé (with the historical centre) and Taulud (or Tawalut, Tawlud), connected with each other and with the coast by dams. Massawa seems to have emerged as a port sometime between the 8th and 10th centuries, after the decline of the nearby port of Adulis about 50 kilometres (31 mi) to the south. Massawa was known to Arab geographers from an early period. Ya'qubi referred to the Red Sea port in his Kitab al-Buldan as Badi, a corruption of its local Tigre name Base, while al-Masudi spoke of it in 935 as Nase. The nearby Dahlak Archipelago was dominated by Arabs, while the coast of Massawa was then controlled by Beja tribes. With the rise of the Sultanate of Dahlak in the 11th century, Massawa became the main link between the Muslim-dominated Red Sea coast and the Christian highlands. Local tradition speaks of the Seyuma Bahr ("Prefect of the Sea"), an independent ruler of Dahlak and the coastal regions, who controlled the trade routes between Ethiopia and the Arabian Peninsula.[5][6]

From the 14th century onward, Massawa attracted increased interest from Christian highland rulers. During periods of political consolidation, Ethiopian rulers expanded their influence up to Massawa, competing with the ruler of Dahlak. War songs of Emperor Yeshaq I mention campaigns to Massawa, where he subdued the deputy of Dahlak. Emperor Zara Yaqob, after consolidating control over the nearby highlands, appears to have reached Massawa in the mid-15th century. He fortified the Gerer peninsula, opposite of the island city, according to a chronicle of Addi Néýammén. It is also reported that both Massawa and Dahlak were pillaged by the Abyssinians in 1464/65, during which "the qadi" was killed (likely a powerful chief official of Massawa).[7][8]

Massawa only irregularly paid tribute to the Abyssinian rulers of the adjacent highlands, such as the Bahr Negash or the governor of the coastal provinces, but it remained connected to the ruler of Dahlak, who himself was a vassal of the Sultan in Aden. [9][10]

Portuguese influence

In the struggle for domination of the Red Sea the Portuguese succeeded in establishing a foothold in Massawa (Maçua) and Arkiko[11] in 1513 by Diogo Lopes de Albergaria, a port by which they entered the allied territory of Ethiopia in the fight against the Ottomans. King Manuel I first gave orders for the construction of a fortress that was never built. However, during Portuguese presence, it was lifted as well as the existing cisterns and wells for the Portuguese Navy watery.[12] It was drawn by D. João de Castro in 1541 in his "Roteiro do Mar Roxo"[13] in their route to attack El Tor and Suez. The captain of the Arkiko was the Portuguese Gonçalo Ferreira, second port on the coast that guaranteed the presence and maintenance of the Portuguese fleets, whenever the port of Massawa was threatened by the Turkish presence.[12] In 1541 the Adalites ambushed the Portuguese at the Battle of Massawa.[14]

Ottoman rule

Massawa rose to prominence when it was captured by the Ottoman Empire in 1557.[15] The Ottomans tried to make it the capital of Habesh Eyalet. Under Özdemir Pasha, Ottoman troops then attempted to conquer the rest of Eritrea. Due to resistance as well as sudden and unexpected demands for more, the Ottomans did not conquer the rest of Eritrea. The Ottoman authorities then tried to place the city and its immediate hinterlands under the control of one of the aristocrats of the Balaw people, whom they wanted to appoint "Naib of Massawa" and almost made answerable to the Ottoman governor at Suakin.[16] In the city's administration, the local qadi of the sharia court occupied a powerful position in the region, as documented starting from the 16th century to the 19th century his jurisdiction extended over a wide areas from the Habab in the north to the northern Afar coast. Ottoman interest in the city was revived in the early 19th century, when in 1809 a Turkish governor was appointed, and in 1813–23 an Egyptian one. From then on Ottoman governors were appointed regularly, and the naibs lost a part of their influence.[17]

In June 1855, Emperor Tewodros II informed the British Consul, Walter Plowden, of his intention to occupy Tigray and make himself master of "the tribes along the coast", he also informed Frederick Bruce that he was determined to seize the port because it was being used by the Turks as "a deposit for kidnapped Christian children" who were being exported as slaves. Both Bruce and Plowden were sympathetic to the Emperor, but the Foreign Office, who considered the Ottomans to be a useful British ally, refused to support the proposed Ethiopian annexation.[18]

In May 1865, Massawa, and later much of the Northeast African coast of the Red Sea, came under the rule of the Khedive of Egypt with Ottoman consent. The Egyptians originally had a poor opinion of Massawa. Many of the buildings were in a poor state of repair and the Egyptian troops were forced to stay in tents. Sanitary conditions were likewise poor and cholera was endemic. Such considerations caused the Egyptians to contemplate abandonment of the port in favour of nearby Zula. However, the Egyptian governor, Werner Munzinger, was determined to improve the conditions of the port and began a programme of reconstruction. Work began in March 1872 when a new government building and customs house was constructed, and by June a school and a hospital was also established by the Egyptians. Dams were also constructed to connect the islands and the coast.[19]

Egyptian control of Massawa was threatened following the defeat at the Battle of Gura. After the Egyptian-Ethiopian War, Emperor Yohannes IV reportedly demanded that the Egyptians should cede both Zula and Arkiko and pay Ethiopia two million pounds in reparations or, failing this sum, grant him the port of Massawa. The Egyptians refused these demands and Yohannes ordered Ras Alula with 30,000 men to advanced on the port. The population was said to have been "much alarmed" at the Ethiopian show of force, however Alula soon returned to the highlands and the Egyptian control of the coastline remained unbroken.[20]

Italian colonization

The British, feeling that the Egyptians were in no position to hold the port, and being unwilling to occupy it themselves or see it fall into the hands of the French, concurred in its seizure by the Italians in February 1885. In 1885–1897, Massawa (in the Italian spelling: 'Massaua') served as the capital of the region, before Governor Ferdinando Martini moved his administration to Asmara. However, the Italians' disastrous defeat at Adwa ended their hopes of expanding further into the Ethiopian highlands.[21]

Many buildings in Massawa were designed and constructed by the Italians, who made a conscious effort to preserve the city's architectural heritage. Although most old structures had to be rebuilt or repaired, they retained their original scale and physical characteristics, as seen in the old Grand Mosque, Gami’ al-Khulafa ar-Rashidin. The Italians also maintained the layout of the city’s streets, preserving the irregular pattern of narrow, dense alleyways, which remains a defining feature of Massawa today. However, most of the city was completely destroyed by the 1921 earthquake. Post-1921 buildings were constructed using reinforced concrete, often faced with coral block or cement plaster, and typically featured multiple storeys with the character being more European. Between 1887 and 1932, they expanded the Eritrean Railway, connecting Massawa with Asmara and then Bishia near the Sudan border, and completed the Asmara-Massawa Cableway. At 75 kilometres (47 mi) long, it was the longest ropeway conveyor in the world at the time.[22][23]

In 1928, Massawa had 15,000 inhabitants, of which 2,500 were Italians: the city was improved with an architectural plan similar to the one in Asmara, with a commercial and industrial area. With the rise of Fascism a segregation policy was implemented and with the passing of the "racial laws" soon became a real system of apartheid. Natives were segregated from residential areas, bars and restaurants reserved for the white population. However these laws did not stop relationships between Italian men and Eritrean women in the colonial territories. The result was a growing number of meticci (mulattos). Though the chief port of Italian Eritrea, Emilio De Bono who inspected the harbor in 1932 reported that the port had to be reconditioned as it was "absolutely lacking in wharves and facilities for the rapid landing and discharge of cargoes." As a result, the quays were widened, the breakwater lengthened to enable the simultaneous discharge of five steamers and the harbour was equipped with two large cranes.[24][25]

During the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, Massawa served as a base for the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, which caused the town to be flooded with Italian soldiers. An American journalist reported at the height of the invasion, "The streets had obviously sprung up over night. Men slept in completely open barracks - just a skeleton frame-work of wood with galvanized iron roof."[26] After the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, Massawa underwent significant and rapid development. The 115-km road to Asmara was improved, and an aerial cableway connecting Massawa with Asmara was constructed. The railway was extended to Taulud, and infrastructure projects included an electric power plant, fuel depots, a cement factory, new residential areas, a naval base on the Abdalqader Peninsula, and a military airport. By 1938, Massawa had 15,000 civilian inhabitants, including 4,000 Italians, along with thousands of soldiers passing through the city.[27]

Following the end of World War II, the port of Massawa suffered damage as the occupying British either dismantled or destroyed much of the facilities. These actions were protested by Sylvia Pankhurst in her book Eritrea on the Eve.[28]

Ethiopian rule

Under the Ethiopian-Eritrean Federation (1952–62), Massawa developed as a naval base with American assistance. During this period, an Orthodox Church and a mosque were built. Unlike in other predominantly Muslim areas of Eritrea, part of Massawa's population supported Eritrea’s union with Ethiopia, viewing it as beneficial for trade and based on historical experience. However, Ethiopian interference in local administration and the increasing dominance of Christians led to various forms of protest, including docker strikes in 1954.[29]

In 1977–78, Massawa was under siege by the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF), but the attacks were repelled by the Ethiopian garrison.[30]

In February 1990, Massawa was captured by the Eritrean People's Liberation Front in a surprise attack from both land and sea during the Operation Fenkil. The battle utilized both infiltrated commandos and speed boats and resulted in the complete destruction of the Ethiopian 606th Corps. The success of this attack cut the major supply line to the Second Ethiopian Army in Asmara, which then had to be supplied by air. In response, the then leader of Ethiopia Mengistu Haile Mariam ordered Massawa bombed from the air, resulting in considerable damage.[31]

Eritrean independence

With Eritrea's de facto independence (complete military liberation) in 1991, Ethiopia reverted to being landlocked and its Navy was dismantled (partially taken over by the nascent national navy of Eritrea).

During the Eritrean–Ethiopian War the port was inactive, primarily due to the closing of the Eritrean-Ethiopian border which cut off Massawa from its traditional hinterlands. A large grain vessel donated by the United States, containing 15,000 tonnes of relief food, which docked at the port late in 2001, was the first significant shipment handled by the port since the war began.[32]

Transportation

Massawa is home to a naval base and large dhow docks. It also has a station on the railway line to Asmara. Ferries sail to the Dahlak Islands and the nearby Sheikh Saeed Island.

In addition, the city's air transportation needs are served by the Massawa International Airport.

Main sights

Buildings in the city include the shrine of Sahaba,[33] as well as the 15th century Sheikh Hanafi Mosque and various houses of coral. Many buildings, for example some unfinished Ottoman buildings, survive. The local bazaar as well. Later buildings include the Imperial Palace, built in 1872 to 1874 for Werner Munzinger; St. Mary's Cathedral; and the 1920s Banca d'Italia. The Eritrean War of Independence is commemorated in a memorial of three tanks in the middle of Massawa.

Climate

Massawa has a hot desert climate (Köppen climate classification BWh). The city receives a very low average annual rainfall amount totalling around 185 millimetres (7.28 in) and consistently experiences soaringly high temperatures during both day and night. The annual mean average temperature approaches 30 °C (86 °F), which is one of the highest found in the world. Massawa is noted for its very high summer humidity despite being a desert city. This combination of the desert heat and high humidity makes the apparent temperatures seem even more extreme. The sky is usually clear and bright throughout the year.

| Climate data for Massawa (1961 to 1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 29.1 (84.4) |

29.4 (84.9) |

31.8 (89.2) |

33.9 (93.0) |

36.8 (98.2) |

40.2 (104.4) |

40.8 (105.4) |

40.3 (104.5) |

38.7 (101.7) |

35.6 (96.1) |

33.1 (91.6) |

30.5 (86.9) |

35.0 (95.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 24.3 (75.7) |

24.3 (75.7) |

25.9 (78.6) |

27.9 (82.2) |

30.0 (86.0) |

33.0 (91.4) |

34.3 (93.7) |

33.9 (93.0) |

32.1 (89.8) |

29.5 (85.1) |

27.1 (80.8) |

25.2 (77.4) |

29.0 (84.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 19.1 (66.4) |

19.1 (66.4) |

20.1 (68.2) |

21.8 (71.2) |

23.5 (74.3) |

25.7 (78.3) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.5 (81.5) |

25.5 (77.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

21.0 (69.8) |

19.7 (67.5) |

22.8 (73.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 34.7 (1.37) |

22.2 (0.87) |

10.2 (0.40) |

3.9 (0.15) |

7.6 (0.30) |

0.4 (0.02) |

7.8 (0.31) |

7.8 (0.31) |

2.7 (0.11) |

22.4 (0.88) |

24.1 (0.95) |

39.5 (1.56) |

183.3 (7.23) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 3.1 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 2.7 | 15.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76.3 | 75.3 | 73.3 | 70.5 | 65.0 | 53.8 | 53.0 | 55.6 | 60.8 | 66.6 | 69.1 | 74.5 | 66.1 |

| Source: NOAA[34] | |||||||||||||

See also

Further reading

- Miran, Jonathan (2009). Red Sea Citizens: Cosmopolitan Society and Cultural Change in Massawa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-35312-2.

Notes

References

- ^ "World Gazetteer – Eritrea". Archived from the original on 12 April 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ^ Phillips, Matt; Carillet, Jean-Bernard (2006). Lonely Planet Ethiopia and Eritrea. Lonely Planet. p. 340. ISBN 1-74104-436-7.

- ^ Bjunior (8 July 2018). "Dadfeatured: ITALIAN MASSAUA" (blog).

- ^ Melake, Kiflemariam (1 May 1993). "Ecology of macrobenthos in the shallow coastal areas of Tewalit (Massawa), Ethiopia". Journal of Marine Systems. 4 (1): 31–44. Bibcode:1993JMS.....4...31M. doi:10.1016/0924-7963(93)90018-H. ISSN 0924-7963.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (1982). History Of Ethiopian Towns. p. 80. ISBN 9783515032049.

- ^ Uhlig, Siegbert. Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: Volume 3: He-N. p. 851.

- ^ Uhlig, Siegbert. Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: Volume 3: He-N. p. 851.

- ^ Connel, Dan; Killion, Tom (2011). Historical Dictionary of Eritrea. Scarecrow Press. p. 160. ISBN 9780810875050.

- ^ Reid, Richard J. (12 January 2012). "The Islamic Frontier in Eastern Africa". A History of Modern Africa: 1800 to the Present. John Wiley and Sons. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-470-65898-7. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ Uhlig, Siegbert. Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: Volume 3: He-N. p. 851.

- ^ Carvalho, Maria João Loução de (2009). Gaspar Correia e dois perfis de Governador: Lopo Soares de Albergaria e Diogo Lopes de Sequeira - Em busca de uma causalidade (Mestrado em Estudos Portugueses Interdisciplinares thesis) (in Portuguese). Universidade Aberta. hdl:10400.2/1484.

- ^ a b Barros, João; de Couto, Diogo (1782). Da Asia (in Portuguese). Vol. 16. Lisbon: Regia Officina Typografica. OCLC 835029242.

- ^ a b "D. João de Castro (1500-1548)". Ciência em Portugal - Personagens (in Portuguese). Instituto Camões. 2003. Archived from the original on 6 March 2011.

Estes roteiros, tal como toda a obra náutica e oceanográfica de D. João de Castro ficaram inéditos em Portugal até aos séculos XIX e XX, com a excepção do Roteiro do Mar Roxo [1541] que foi divulgado nos séculos XVII e XVIII através de diversas traduções, como acima foi descrito.

- ^ Hespeler-Boultbee, John. A Story in Stones: Portugal's Influence on Culture and Architecture in the Highlands of Ethiopia 1493-1634. CCB Publishing. p. 188.

- ^ Massawa: Pearl of the Red Sea

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (1997). The Ethiopian borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century. Lawrenceville: Red Sea Press. p. 270. ISBN 0-932415-19-9.

- ^ Uhlig, Siegbert. Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: Volume 3: He-N. p. 851.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (1982). History of Ethiopian towns from the mid 19th century to 1935. p. 127.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (1982). History of Ethiopian towns from the mid 19th century to 1935. p. 135.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (1982). History of Ethiopian towns from the mid 19th century to 1935. p. 135.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (1982). History of Ethiopian towns from the mid 19th century to 1935. p. 135.

- ^ Killion, Tom (1998). Historical Dictionary of Eritrea. Lanham, MD/London: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-3437-5.

- ^ Uhlig, Siegbert. Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: Volume 3: He-N. p. 852.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (1982). History of Ethiopian towns from the mid 19th century to 1935. p. 339.

- ^ Santoianni, Vittorio. Il Razionalismo nelle colonie italiane 1928-1943: la «nuova architettura» delle Terre d'Oltremare (PDF) (PhD thesis) (in Italian). Università degli Studi di Napoli "Federico II". p. 65.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (1982). History of Ethiopian towns from the mid 19th century to 1935. p. 340.

- ^ Uhlig, Siegbert. Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: Volume 3: He-N. p. 852.

- ^ Wrong, Michela (2005). "The Feminist Fuzzy-Wuzzy". I Didn't Do it for You: How the World Betrayed a Small African Nation. New York: Harper-Perennial. pp. 116–150. ISBN 0-00-715096-2.

- ^ Uhlig, Siegbert. Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: Volume 3: He-N. p. 852.

- ^ Uhlig, Siegbert. Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: Volume 3: He-N. p. 852.

- ^ Ethiopia: "Mengistu has Decided to Burn Us like Wood": Bombing of Civilians and Civilian Targets by the Air Force (PDF). News from Africa Watch (Report). Human Rights Watch. 24 July 1990.

- ^ "Horn of Africa, Monthly Review, covering the months between November and December, 2001" (PDF). UN-OCHA. Retrieved 24 February 2009.

- ^ Gebremedhin, Naigzy; Denison, Edward; Mebrahtu, Abraham; Ren, Guang Yu (2005). Massawa: A Guide to the Built Environment. Asmara: Cultural Assets Rehabilitation Project. OCLC 1045996820.

- ^ "Massawa Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 24 June 2015.