Sir John Fogge (c. 1417–1490) was an English courtier, soldier and supporter of the Woodville family under Edward IV who became an opponent of Richard III.

Family

There is some uncertainty over the parents of Fogge. The most well-known source, The Family Chronicle of Richard Fogge of Danes Court in Tilmanstone shows John as the son of Sir William Fogge and an un-named daughter of William Wadham, Sir William Fogge's second wife.[1] The Antiquary states that he was the son of Sir William and his first wife, a daughter of Sir William Septvans[2] (d. 1448[3]). However, Rosemary Horrox argues that he was the son of another John Fogge, Sir William's younger brother, and Jane Cotton.[4]

John Fogge was born about 1417 and it seems certain that he was the grandson of Sir Thomas Fogge—as he was eventually the recipient of his inheritance—[4](d. 13 July 1407[5]) and Joan de Valence (d. 8 July 1420),[6] widow of William Costede of Costede, Kent, and daughter of Sir Stephen de Valence of Repton.

In a lawsuit in 1460 he calls himself son and heir of John.[7][8][9]

In The Family Chronicle of Richard Fogge of Danes Court in Tilmanstone published in 1868, it is strongly suggested that the William Fogge who married the daughters of Wadham and Septvans was the William Fogge (1396[1] – by February 1447[4]) who was the grandson and heir of Sir Thomas Fogge (d. 13 July 1407[5]) by his son Thomas Fogge (d. 1405[1]). The Family Chronicle of Richard Fogge of Danes Court in Tilmanstone also mentions another son of Sir Thomas Fogge (d. 13 July 1407[5]), John Fogge, who Sir Thomas appointed an executor of his will.[1]

In the History of Parliament entry for Sir John Fogge, Josiah C. Wedgwood establishes in 1936 that 'in his suit for Tonford etc., Aug. 1460, he calls himself s. and h. of John, deceased, who was a younger son of Sir Thomas Fogge M.P. Sir John's mother was Jane Catton.'[10]

Tonsure

Gillian Draper writes:

John Fogge, the grandson of Sir Thomas, was probably born in 1417, and was ordained to the first tonsure in Canterbury Cathedral in 1425. This was a first step into the six or seven holy orders, but many boys took it and it did not mean they were firmly destined for the priesthood. Rather it represented a stage in their early education; for some boys it occurred about age seven to eight years. John Fogge was one of several boys or young men ordained to the first tonsure in 1425 including William Fogge, presumably John Fogge's cousin, and one John Cobbes.[11]

Career

According to Horrox, Fogge had reached the age of majority by 1438, but only came to prominence when he inherited the lands of the senior line on the death of Sir Thomas's grandson and heir, William by February 1447.[4]

Fogge was an esquire to Henry VI by 1450, and in that year was involved in the suppression of the rebellion of Jack Cade.[4] He was appointed Sheriff of Kent in November 1453.[4] He was made Comptroller of the Household in 1460 under Henry VI, and knighted the following year.[citation needed]

Despite his earlier service under Henry VI, when the future Edward IV landed in England in June 1460, Fogge joined the Yorkists, and was granted Tonford in Thanington and Dane Court in Boughton under Blean, manors to which he claimed to be entitled by reversion.[4]

After the Yorkist victory at the Battle of Towton on 29 March 1461, 'Fogge emerged as a leading royal associate in Kent, heading all commissions named in the county'. In 1461, he was granted the office of Keeper of the Writs of the Court of Common Pleas,[12] and took part in the investigation of the possible treason of Sir Thomas Cooke, Lord Mayor of London.[13] He was Treasurer of the Household to Edward IV from 1461 to 1468, as well as a member of the King's council, and in March 1462 he and others were granted custody of the lands of John de Vere, 12th Earl of Oxford, forfeited to the crown as a result of the Earl's attainder. In 1469, it was alleged that Fogge was among those whose 'covetous rule and gydynge' had brought Edward IV and the kingdom to 'great poverty and misery'.[4][14]

In 1461 and 1463 he was elected to Parliament as Knight of the Shire for Kent, and in 1467 as MP for Canterbury. He was Sheriff of Kent in 1472 and 1479.[citation needed]

According to Horrox, his name is not found in commissions during the Readeption of Henry VI, suggesting the possibility that he went into exile with Edward IV.[4]

When Edward IV regained the throne, Fogge was rewarded for his loyalty with grants of land, as well as a grant for twelve years of gold and silver mines in Devon and Cornwall.[15][4] During this period Fogge built close ties to the Prince of Wales,[4] and from 1473 was a member of his council and administrator of his property.[citation needed] He was made Chamberlain jointly with Sir John Scott. He again represented Kent in parliament in 1478 and 1483.[14]

In 1483, the future Richard III of England appointed himself Protector of Edward IV's young son and heir, Edward V, accusing the Woodvilles of plotting against him. Sir Thomas More says that Fogge took sanctuary at this time, and that Richard III was prepared to treat him with favour. Despite this apparent reconciliation, Fogge supported Richard Guildford in Kent against Richard III, a rising in support of Edward V, and became part of the unsuccessful Buckingham's rebellion.[16][17][18]

The rising was blocked at Gravesend by John Howard, 1st Duke of Norfolk, and the rebel force retreated.[19] Fogge was attainted, and much of his property was granted to Sir Ralph Ashton, who had been loyal to the King, and who was already in conflict with Fogge over a portion of the Kyriell inheritance from Fogge's first marriage. In February 1485 Fogge bound himself to good behaviour and was pardoned, and four of his manors were returned to him.[4][20][21]

Fogge was a supporter of Henry Tudor. After the latter's accession, however, perhaps due to advancing age, Fogge played little part in national affairs.[4]

Fogge left a will dated 15 July 1490,[22][23] and had died by 9 November of that year.[4]

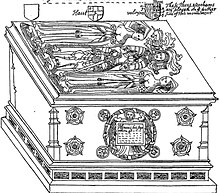

He built and endowed the church at Ashford, Kent as well as the College at Ashford. He was buried beneath a handsome altar-tomb in the church, where he is also commemorated in a memorial window.[24]

The Fogge arms were Argent on a fess between three annulets sable three mullets pierced of the first. The crest was a unicorn's head, argent.[25] At the Siege of Rouen in 1418, a Thomas Fogge who was likely his great-grand-uncle, carried the same arms differenced by having unpierced mullets.[26][self-published source][better source needed]

Sir John Fogge Avenue, built on the former Joint Services School of Intelligence site in Ashford, is named after him.

Literary references

A character named 'Jon Fogge', who appears to be based on this knight, appears in Marjorie Bowen's 1929 novel Dickon about the life of Richard III. In the novel he serves as a sort of sinister shadow, portending the violent fate of the king.

Marriages and issue

Fogge married firstly, by the early 1440s, Alice de Criol or Kyriell, daughter of the Yorkist soldier Sir Thomas de Criol of Westenhanger, beheaded after the Second Battle of St. Albans by order of Margaret of Anjou.[27] The marriage brought him Westenhanger Castle.[28][29] Alice de Criol or Kyriell died between February 1462 when she was amongst those endowing two chaplains to pray for her father and others slain at Northampton, St. Albans and Shirebum,[30] and 9 May 1462.[31] They had a son and heir,

- John Fogge (d.1501), who married Joanne Leigh, daughter of Sir Richard Leigh,[25] Lord Mayor of London (1460, 1469). Their son,

- Sir John Fogge (d.1533), Marshal of Calais and Sheriff of Kent, married Margaret Goldwell, daughter of Jeffrey Goldwell (brother of James Goldwell, Bishop of Norwich), by whom he had three sons and three daughters:[25][4]

- Sir John Fogge (d.1564) of Repton in Ashford, Kent, eldest son, Sheriff of Kent in 1545, who married firstly Margaret Brooke, the daughter of Thomas Brooke, 8th Baron Cobham (d. 19 July 1529) by his first wife, Dorothy Heydon, and secondly Catherine, the daughter of one Holand of Calais.[25][32][33]

- William Fogge (d.1535) of Canterbury, buried in Canterbury Cathedral,[25] and as by his will he expresses it, near his ancestors. He gave by it to the bell-ringers of Christ-church, for the pele, and for the making of his poole 3s. 4d. He left an infant son Francis by Katherine his wife.[34] His only son, "Slayn at Guinse," as said in an old MS.[1]

- George Fogge (died c.1591) of Brabourne and Repton, who married firstly Margaret Kempe (daughter of Sir William Kempe of Olantigh by his second wife, Eleanor Browne, widow of (see below) Thomas Fogge (d. 16 August 1612), and daughter and heir of Robert Browne, son of Sir Thomas Browne of Betchworth Castle), and secondly Honor Palmer, daughter of Sir Thomas Palmer.[25]

- Margaret Fogge, who married Sir Humphrey Stafford.[25] – but see below

- Abigail Fogge, who married Cranmer Brooke (died c.1547) of Ashford, son of Thomas Brooke (third son of Thomas Brooke, 8th Baron Cobham (d. 19 July 1529)), and Susan Cranmer, niece of Archbishop Thomas Cranmer.[25][35][36]

- Bridget Fogge (d.1557[37]), a maid of honour to Queen Katherine of Aragon. She married Anthony Lowe (d.1555[37]), Esquire, of Alderwasley, 'gentleman of the bed-chamber and standardbearer to King Henry VII, King Henry VIII, King Edward VI, and Queen Mary'.[37][38][39][40]

- Daughter whose name is not given in the Fogge pedigree,[25] Lettice.[41]

- Sir John Fogge (d.1533), Marshal of Calais and Sheriff of Kent, married Margaret Goldwell, daughter of Jeffrey Goldwell (brother of James Goldwell, Bishop of Norwich), by whom he had three sons and three daughters:[25][4]

John Fogge married secondly, between February 1462 (when his first wife was alive)[30] and 9 May 1462,[31] Alice Haute or Hawte (born c.1444), the daughter of William Haute, Esquire, MP (d.1462[31]) of Bishopsbourne, Kent,[42] and Joan Woodville, daughter of Richard Woodville.[43][44] Richard Woodville was also the father of Richard Woodville, 1st Earl Rivers, and the grandfather of Elizabeth Woodville,[44][4] [45] and Fogge's second wife, Alice Haute was thus Elizabeth Woodville's first cousin. After her marriage to Edward IV, Elizabeth Woodville brought her favourite female relatives to court. Fogge's second wife, Alice Haute, was one of her five ladies-in-waiting during the 1460s.[46]

By Alice Haute, Fogge had a son and three daughters:

- Thomas Fogge (d. 16 August 1512), esquire, of Ashford, Great Mongeham, Sutton Farm (in Sutton), Tunford (in Thanington), and Walmer, Kent, Sergeant Porter of Calais to Henry VII and Henry VIII. He married before 9 December 1509 Eleanor Browne, daughter of Robert Browne, esquire, and granddaughter of Sir Thomas Browne. They had two daughters, Alice (wife of Edward Scott and Robert Oxenbridge, Knight.) and Anne (wife of William Scott and Henry Isham). He was buried in the church at Ashford. He left a will dated 4 August 1512, proved 16 October 1512 (P.C.C. 9 Fetiplace).[47][48][49][50] Eleanor married secondly Sir William Kempe, Knight, of Ollantigh of Kent and died on 16 September 1559.[49][51]

- Anne Fogge.

- Elizabeth Fogge.

- Margaret Fogge, who married her father's ward,[4] Sir Humphrey Stafford (d. 22 September 1545) of Cottered and Rushden, Hertfordshire, by whom she was the mother of three sons and three daughters, including Sir Humphrey Stafford, who married Margaret Tame,[52] daughter of Sir Edmund Tame, and Sir William Stafford, who married Mary Boleyn.[53][54] Stafford was the son of Humphrey Stafford (died 1486).

Many sources state that Sir Thomas Greene married Fogge's daughter, Joan (or Jane), by whom he was the father of Maud Green, mother of Katherine Parr.[55] However Fogge's will, as transcribed by Pearman in 1490, states that he has three daughters, Anne, Elizabeth and Margaret, and makes no mention of any other daughter.[22] The official biographers of Katherine Parr, Susan E. James and Linda Porter, state that Joan was the granddaughter of Fogge.[56][57] It could be possible that John disowned Joan for unknown reasons, or that she had already died before the will was made, probably after the birth of Joan's younger daughter Maud, who could've been born in 1490.[58][59] The perhaps most likely explanation is that as a married woman Joan and her husband had already received her dowry. Anne, Joan's eldest daughter, was born in 1490,[60] which might indicate a recent marriage. Joan might have been of about the same age as the three daughters mentioned in Sir John Fogge's will who were all unmarried and left sums towards their dowries and to the 'Governance and Guiding' of his wife Alice.[61]

In the Family Chronicle of Richard Fogge of Danes Court in Tilmanstone, it is mentioned in the Fogge family pedigree that Sir John Fogge had four daughters, although only three were mentioned by name so it is likely that the unspecified daughter is Joan.[62]

And the Widville pedigree, taken in 1480–1500, tells us that Iohanna nupta domino Thome Greene militi. This Iohanna was the daughter of Alicia nupta domino Iohanni Fogge militi. And this Alicia was the daughter of Willelmus Hault armiger by a lady Wideuille, to be more specific, the daughter of Ricardus Wideuille armiger and a filia de Bedelsgate.[63]

Joan was their eldest daughter, born between William who died as a child and Thomas.[63]

On 10 July 1471 Sir John Fogge, knight, was granted the wardship and marriage of Thomas, son and heir of Thomas Grene of Norton, county Northampton, knight, deceased.[64] Like her sister Margaret, Joan also married her father's ward.

Sir John Fogge (d. 1490) might also have had another daughter not mentioned in his will, the mother of his 'nephew' (likely grandson, the word could be used also in that sense then) John ffoughler (possibly John Fuller or John Fowler), who was to inherit if his eldest son John Fogge perished without heirs. This could indicate that this daughter was also from his first marriage.[65]

His sentimental bequests were all reserved for his two surviving sons and his wife Alice, though Gillian Draper leaves room for the possibility that he intended for a mass book to pass to one of his daughters:

Sir John Fogge had a private chapel at the manor house of Repton as well as the Fogge chapel in Ashford church. His bequests of the ecclesiastical equipment used at the chapel at the house reveal aspects of life at the manor and the way in which he considered that equipment to be both family possessions and dedicated to service in the chapel. Fogge left his wife Alice a vestment of velvet, a mass book which she was to choose from the two in the chapel, two basins of silver for the altar, a cross and two cruets all of silver and gilt, and a gilt sacring bell. Alice was to keep all of these for her whole life and most of them – apart from the velvet vestment and the mass book – were then to pass to Fogge's son John or his heirs with the intention that they should remain for the use of the chapel at Repton. The velvet vestment could have been considered a personal item with which Alice may have had some involvement, say in its embroidery, or something she might convert for her own wear, and thus unsuitable to pass on. The fact that Alice was to choose the mass book and keep it for her whole life but that it would then not pass to Fogge's son suggests two things: firstly, that she was literate, and secondly that she might herself bequeath the book to whomever she chose, perhaps a daughter, since mothers were the earliest teachers of children, both girls and boys. Sacred books were very important since the 'dynamic of literacy was religion', although parents such as the Fogges also required their children to learn pragmatic literacy for letter-writing and estate management. Eastern Kent, where the Fogges lived and held lands and manors, was an area of extensive literacy mainly because of the proximity of the Cinque Ports with their early traditions of civic record-keeping. Apart from a special decorated 'Standyng Cuppe of gilt' which Sir John bequeathed to John junior, Dame Alice was to receive all the rest of the domestic goods and chattels at Repton to keep or give away as she chose.[66]

Tilting helmet

There is a tilting helmet hanging above Sir John Fogge's monument in Ashsford Church. Weight 23 lb. 15 oz.[67]

Edward V

Sir John Fogge was on the Council in January 1483. Sir Thomas More says— "Fogge had been Treasurer of the Household to Edward IV. Richard III had granted him an ostentatious pardon, but Fogge remained hostile." He was on none of Richard's comns., and was attainted by the Parliament of 1484, "leader of the Duke of Buckingham's rising in Kent." Browne, Fogge and Guildford forfeited their Kentish estates which were handed to the custody of William Mauleverer. Browne lost his head, Fogge took sanctuary. Richard sent for him, shook hands, and pardoned him, 24 February 1485.[68]

Historian Rosemary Horrox has suggested that the mother of Richard III's daughter Katherine Plantagenet was Katherine Haute.

Sir John Fogge had been close with Edward V, one of the Princes in the Tower. John Fogge, Knight, had been appointed Chamberlain to the Prince when he was nine months old.[2] Since John Fogge had gone into sanctuary with Elizabeth Woodville he may have been there when little 9-year-old Richard of Shrewsbury was handed over from his mother's care and into the Duke of Gloucester's, the later Richard III's care.[69]

Indenture and friendship

Gillian Draper writes:

An indenture made after his death by his widow Alice is our major source for the detailed arrangements Fogge made for his commemoration. In 1512 Alice confirmed and extended these arrangements. At this time the College apparently had more personnel than in the 1460s: a master, who was to carry out the three traditional obit services, Mass, dirige and Morrow-Mass, together with three priests, two boy choristers, two clerks and two other priests. The clerk was to ring the new Great Bell of the church in the tower which Fogge had caused to be built, and six wax tapers were to be lighted, presumably on the high altar. This was immediately adjacent to Fogge's tomb and just to the east of the choir with its sixteen stalls with their misericords, where presumably the master and the others sang. When the Great Bell was rung, it would draw the attention of the townspeople and the town's poor: after their attendance at the obit a meal of southern beef, bread and ale was to be provided for thirteen of them, plus a penny each in cash. This was entirely conventional but relatively generous, a total of 31s. 6d. was to be spent each year. However, it does give a glimpse of the link between the Fogge family and the townsfolk, people among whom he had spent many years, rather than with the wealthy and powerful several of whom appeared in the north transept windows which Fogge glazed. Alice confirmed the obit for John's soul for another sixty years and extended it to include the souls of herself, their children, Sir William Haute and his wife Joan Woodville (her parents), and their friends – those already dead and those still to die. This remembrance of friends, while traditional, echoed the concern of Sir John in founding the College and having his friends or allies – including men of the Church – painted in its windows, men with whom he had been through difficult political times and, just possibly, military activity.[70]

In February 1462 Sir John Scott and Sir John Fogge, and Alice, Sir John Fogge's first wife and Kyriel's daughter, 'endowed two chaplains to pray for Home and Kyriel and all others slain at Northampton, St. Albans and Shirebum (Towton) — whence we may suppose that they were present together in these fields.'[30] In November 1467 he endowed an oratory for prayers for Kyriel, Horne and Colt and all slain "for the King's right ", as before:[71]

Nov. 18. Westminster.

Grant in frank almoin to Thomas Wilmote, vicar of the church of Asshettesford, co. Kent, of the manor and town of Dounton Weylate, co. Essex, with the advowson of the church of Dounton, the manor of Preston and Hoo, co. Sussex, lately pertaining to the priory of Okeburn, and a yearly pension of 100''s''. which the prior of Lewes is bound to render to the king from an impost lately due to the abbey of Cluny, to hold with all appurtenances quit of all farms, rents, arrears, tenths, fifteenths and actions and demands from 4 March, 1 Edward IV. to find two chaplains and two secular clerks to celebrate divine service in the said church for the good estate of the king and his kinsman George, archbishop of York, and John Fogge, knight, and Alice his wife and for their souls after death and the souls of Richard, late duke of York, the king's father, Edmund, late earl of Rutland, the king's brother, and Richard, earl of Salisbury, the king's uncle, and Thomas Kyryell, knight, Robert Hoorne and Thomas Colt, esquires, and all others of the county of Kent killed in the conflicts at Northampton, St. Albans and Shirbourne for the king's right and the good of the realm, according to the ordinances of the said John Fogge. By p.s.[72]

Josiah C. Wedgwood writes: 'In spite of a modern novelist, there is little, save his indictment of Cook, that this close examination can bring up against a good soldier, a good comrade and a powerful official.'[73]

Notes

- ^ a b c d e Kent Archaeological Society (1858). Archaeologia cantiana. Getty Research Institute. [London] Kent Archaeological Society. Family tree between p. 124 and p. 125.

- ^ a b Scott, James Renat (1876). Memorials of the Family of Scott, of Scot's-Hall, in the County of Kent. With an Appendix of Illustrative Documents. Boston Public Library. London: J. R. Scott. p. 175.

- ^ "Monuments in the cathedral | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 8 February 2025.

Some little distance higher was an inscription in French, with the figure of a knight in armour, and shields of arms, for Sir William Septvans, who died in 1407. (fn. 4) Near it was an inscription in Latin, with the figures of a knight and his wife, with their shields of arms, for Sir William Septvans, who died anno 1448, and Elizabeth his wife, daughter of Sir John Peche, and these verses, Sum quod eris, volui quod vis, credens quasi credis. Vivere forte diu, mox ruo morte specu Cessi quo nescis, nec quomodo, quando sequeris. Hinc simul in cælis ut simus quoque preceris. 4. This Sir William Septvans, says Weever, p. 234, served in the wars of France under king Edward III. It appears by his will in the consistory court of Canterbury, that his residence was at Milton, near Canterbury, and that which was very remarkable, he gave manumission to divers of his slaves and natives.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Horrox 2004.

- ^ a b c "FOGG, Sir Thomas (d.1407), of Repton in Ashford and Canterbury, Kent. | History of Parliament Online". www.historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 9 February 2025.

- ^ According to Pearman she died in 1425.

- ^ Sir John Fogge of Ashford, by Sarah Bolton, p. 202. The Ricardian Society.

- ^ Draper, Gillian (1 January 2023). "Sir John Fogge's Tomb: The Culmination of his Commemorative Scheme in Ashford Church, Kent". Transactions of the Monumental Brass Society XXIV, 68-92.

- ^ Reference: C 1/11/413. Catalogue Description: Fogge v. Boteller. Plaintiffs: John Fogge, esq. Defendants: John Boteller and Thomas Draper. Subject: Money left to petitioner by his mother Joan Catton. Date: 1432–1443, possibly 1467–1470. Held by: The National Archives, Kew". 1432–1443, possibly 1467–1470.

- ^ Wedgwood Josiah C. (1936). History Of Parliament (1439-1509). pp. 339–340.

- ^ Draper, Gillian (1 January 2019). "Sir John Fogge and the Rebuilding of Ashford Church, Kent 1475–1483". Archaeologia Cantiana. p. 253.

- ^ Lander 1971, p. 180.

- ^ Okerlund 2006, p. 104.

- ^ a b Ross 1981, p. 106.

- ^ Lyte 1901, p. 213.

- ^ Kendall 1972, p. 261.

- ^ Ross 1981, p. 112.

- ^ Bennett1987, pp. 41–43.

- ^ Kendall 1972, p. 271.

- ^ Kendall 1972, p. 276.

- ^ Ross 1981, p. 119.

- ^ a b Pearman 1868, pp. 123–33.

- ^ According to Horrox, his will is dated 9 July 1490.

- ^ Smith 1859, p. 106.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i T.G.F. 1863, p. 125.

- ^ Timms, Brian (October 2013). "Foster Roll of Arms – 219 – Thomas Fogge". briantimms.fr. Archived from the original on 19 March 2016.

- ^ Pearman 1868, p. 25.

- ^ Fortified England 2014.

- ^ Hasted 1799, pp. 63–78.

- ^ a b c Wedgwood Josiah C. (1936). History Of Parliament (1439-1509). p. 340.

- ^ a b c Abstract of will of William Haute, Esquire, proved October 1462, in N.H. Nicolas, Testamenta Vetusta: being illustrations from wills, of manners, customs, &c. (Nichols & Son, London 1826), I, p. 300. The will identifies him as the father.

- ^ Waller 1877, p. 112.

- ^ Richardson IV 2011, p. 381.

- ^ "Monuments in the cathedral | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 8 February 2025.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Waller 1877, p. 111.

- ^ Pearman 1868, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Derbyshire Archaeological and Natural History Society (1881). Journal of the Derbyshire Archaeological and Natural History Society. Vol. III. London Natural History Museum Library. London: Bemrose & Sons, 23, Old Bailey; And Derby. p. 167.

HERE LYETHE ANTONEYE LOWE, ESQUYER, SERVANTE TO KYNGE HENRY THE VII., KYNG HENRY THE VIII., KYNG EDWARDE YE VI. & QUEENE MARIE YE I, BURIED YE 4 OF DECB. A.D. 1555. Bridget, his wife, was the daughter of Sir John Fogge, of Richbury, in Kent, comptroller of the household, and privy counsellor to King Henry VII., and was herself a maid of honour to Queen Katherine of Arragon. By her will, dated September 25th, 1557, and proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, October the 8th, following, she desires to be 'buried in the chauncell of the p'sh churche of Wyrkisworth, near unto my said late husband, Anthony Lowe, and at my buryall to be such convenyante expenses and necessarye observyances as to my worshyp and degree shall apperteyne.'

- ^ "WIRKSWORTH—Parish Records 1608–1899—MIs". wirksworth.org.uk. Retrieved 13 February 2025.

"In the chancel are several striking memorials, in particular the chest tomb of Anthony LOWE (d 1555). He was Lord of the Manor of Alderwasley and Ashleyhay, Gentleman of the Bedchamber and Standard Bearer to Henry VII, Henry VIII, Edward VI and Queen Mary. On the wall behind are the Royal Arms. Pevsner considers this to be the best monument in the church and completely in the new Renaissance style"— M. R. Handley – St. Mary the Virgin, Wirksworth – A Guide and History. For wording see: Ch076 in MI Section

- ^ "WIRKSWORTH—Parish Records 1608–1899—MIs". wirksworth.org.uk. Retrieved 13 February 2025.

[Ch076]..... Here lyethe ANTONYE LOWE esquyer,servant to Kynge HENRY the VII,Kynge HENRY the VIII,Kynge EDWARD ye VI,Quene MARIE ye I,buried ye XXI day of Decemb AD 1555.(Tomb with Alabaster effigy)

- ^ Morris, The Rev. F. O. (Francis Orpen) (1840). A Series of Picturesque Views of Seats of the Noblemen and Gentlemen of Great Britain and Ireland. With Descriptive and Historical Letterpress. Vol. IV. Harold B. Lee Library. London: William Mackenzie, 69, Ludgate Hill. Edinburgh and Dublin. p. 30.

Anthony Lowe, was Gentleman of the Bedchamber and Standard-bearer to King Henry the Eighth, King Edward the Sixth, and Queen Mary.

- ^ Reference: C 1/1501/34-37. Catalogue Description: Fogge v. Fogge. Plaintiffs: Lettice, a daughter of Sir John Fogge, deceased. Defendants: Jane Fogge, late his wife, and John Fogge, knight, her son. Subject: Legacy partly payable out of lands of John Kyrrell (Kyryell) and partly out of goods of Bishop Goldwell. Kent ?. SFP. Date: 1386–1558. Held by: The National Archives, Kew". 1386–1558.

- ^ L.S. Woodger, 'Haute, William (d.1462), of Bishopsbourne, Kent', in J.S. Roskell, L. Clark and C. Rawcliffe (eds), The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1386–1421 (Boydell & Brewer 1993), History of Parliament online.

- ^ Adams 1986, p. 103.

- ^ a b Fleming 2004.

- ^ Paget, p. 95.

- ^ Harris 2002, p. 218.

- ^ Hitchin-Kemp 1902, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Smith 1859, pp. 107–08.

- ^ a b "The Visitations of Kent, Taken in the Years 1530-1 by Thomas Benolte, and 1574 by Robert Cooke. Volume 74". www.familysearch.org. p. 13. Retrieved 8 February 2025.

- ^ "The Visitations of Kent, Taken in the Years 1530-1 by Thomas Benolte, and 1574 by Robert Cooke. Volume 74". www.familysearch.org. p. 17. Retrieved 8 February 2025.

- ^ Stow, John (1735). A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster, Borough of Southwark: And Parts Adjacent : the Whole Being an Improvement of Mr. Stow's and Other Surveys, by Adding Whatever Alterations Have Happened in the Said Cities, Etc. to the Present Year. T.(J.) Read. p. 680.

- ^ Richardson I 2011, pp. 120–21.

- ^ Richardson II 2011, pp. 224–25.

- ^ Richardson IV 2011, p. 64.

- ^ Richardson III 2011, p. 290.

- ^ Porter 2010, p. 17.

- ^ James 2009, p. 14.

- ^ "Maud Green b. 1490 Northamptonshire, England d. 01 Dec 1531 England: The Kingealogy".

- ^ "Maud (Matilda) Green – born 1490".

- ^ Great Britain. Public Record Office (1898). Calendar of inquisitions post mortem and other analogous documents preserved in the Public Record Office. [2d ser.]. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill University Library. London, Printed for H. M. Stationery Off. by Eyre and Spottiswoode, printers to the Queen. p. 163.

Thomas Grene, knight. Writ 12 November, inquisition 13 March, 22 Henry VII." [1507] "He died 9 November last, seised in fee of all the under-mentioned manors and lands &c. Anne Grene, aged 17 years and more, and Maud Grene, aged 13 years and more, are his daughters and heirs.

- ^ Augustus John Pearman (1868). History of Ashford. Harvard University. H. Igglesden. p. 128.

- ^ Family Chronicle of Richard Fogge of Danes Court in Tilmanstone, p. 124–125.

- ^ a b Blair, C. H. Hunter (Charles Henry Hunter) (1930). Visitations of the North; Or, Some Early Heraldic Visitations Of, and Collections of Pedigrees Relating To, the North of England. Part III. A Visitation of the North of England Circa 1480–1500. The Publications of the Surtees Society Vol. CXLIV. Published for the Society by Andrews & Co., Sadler Street, Durham, And Bernard Quaritch, 11 Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. 1930. pp. 57–58.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Calendar of the Patent Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office. Prepared Under the Superintendence of the Deputy Keeper of the Records. Edward IV. Henry VI. A.D. 1467–1477 (PDF). Published by Authorlty of Her Majesty's Principal Secretary of State for the Home Department. London: Printed for Her Majesty's Stationery Office, by Eyre and Spottiswoode, Printers to the Queen's Most Excellent Majesty. 1900. p. 272.

July 10. Westminster. Grant to John Fogge, knight, of the custody of all lordships, manors, Westminster, lands, rents, services and possessions late of Thomas Grene of Norton, co. Northampton, knight, deceased, tenant in chief, during the minority of Thomas his son and heir, and the custody and marriage of the latter without disparagement and so from heir to heir. By p.s.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Augustus John Pearman (1868). History of Ashford. Harvard University. H. Igglesden. pp. 124–125.

- ^ Draper, Gillian (1 January 2019). "Sir John Fogge and Rebuilding of Ashford Church Kent 1475–1483". Archaeologia Cantiana: 261.

- ^ Kent Archaeological Society (1858). Archaeologia cantiana. Getty Research Institute. [London] Kent Archaeological Society. p. 132.

- ^ Wedgwood Josiah C. (1936). History Of Parliament (1439-1509). p. 341.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Kendall, Paul Murray (1955). Richard the Third. London: George Allen & Unwin LTD. p. 223.

- ^ Draper, Gillian (1 January 2023). "Sir John Fogge's Tomb: The Culmination of his Commemorative Scheme in Ashford Church, Kent". Transactions of the Monumental Brass Society XXIV, 68-92: 89.

- ^ Wedgwood Josiah C. (1936). History Of Parliament (1439-1509). p. 341.

- ^ Calendar of the Patent Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office. Prepared Under the Superintendence of the Deputy Keeper of the Records. Edward IV. Henry VI. A.D. 1467–1477 (PDF). Published by Authorlty of Her Majesty's Principal Secretary of State for the Home Department. London: Printed for Her Majesty's Stationery Office, by Eyre and Spottiswoode, Printers to the Queen's Most Excellent Majesty. 1900. pp. 42–43.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Wedgwood Josiah C. (1936). History Of Parliament (1439-1509). p. 342.

References

- Adams, Alison, ed. (1986). The Changing Face of Arthurian Romance. Cambridge: The Boydell Press.

- Bennett, Michael (1987). The Battle of Bosworth.

- Fleming, Peter (2004). "Haute family (per. c.1350–1530)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/52786. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Westernhanger Castle, Westhanger Castle, Westernhanger Manor House, Westyngehangre, Kiriel Castle". Fortified England. 2014. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014.

- Hasted, Edward (1799). "Parishes: Stanford". The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent: Volume 8. Canterbury: W. Bristow. pp. 63–78.

- Harris, Barbara J. (2002). English Aristocratic Women, 1450–1550. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hitchin-Kemp, Frederick (1902). A General History of the Kemp and Kempe Families. London: The Leadenhall Press. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- Horrox, Rosemary (2004). "Fogge, Sir John (b. in or before 1417, d. 1490)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/57617. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Lyte, H.C. Maxwell, ed. (1901). Calendar of the Patent Rolls . . . Edward IV, Edward V, Richard III, A.D. 1476–1485. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- James, Susan (2009). Katherine Parr: Henry VIII's Last Love. p. 14.

- Kendall, Paul Murray (1972). Richard III.

- Lander, J.R. (1971). Conflict and Stability in Fifteenth-century England.

- Okerlund, Arelene (2006). Elizabeth, England's Slandered Queen.

- Paget, Gerald. The Lineage and Ancestry of H.R.H. Prince Charles, Prince of Wales. Vol. I. p. 95.

- Pearman, A.J. (1868). History of Ashford. Ashford: H. Igglesden. p. 123. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- Porter, Linda (2010). Katherine, the Queen: The Remarkable Life of Katherine Parr, the Last Wife of Henry VIII. p. 17.

- Richardson, Douglas (2011). Everingham, Kimball G. (ed.). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. Vol. I (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. ISBN 978-1449966379.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Richardson, Douglas (2011). Everingham, Kimball G. (ed.). Plantagenet Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. Vol. II (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. ISBN 978-1449966348.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Richardson, Douglas (2011). Everingham, Kimball G. (ed.). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. Vol. III (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. ISBN 978-1449966393.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Richardson, Douglas (2011). Everingham, Kimball G. (ed.). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. Vol. IV (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. ISBN 978-1460992708.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Ross, Charles (1981). Richard III. University of California Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-520-04589-7.

- Smith, Herbert L. (1859). "Notes of Brasses, Memorial Windows and Escutcheons Formerly Existing in Ashford and Willesborough Churches". Archaeologia Cantiana. II. London: Kent Archaeological Society: 103–110. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- T.G.F. (1863). "Family Chronicle of Richard Fogge of Danes Court in Tilmanstone". Archaeologia Cantiana. V. London: Kent Archaeological Society. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- Waller, J.G. (1877). "The Lords of Cobham, Their Monuments and the Church". Archaeologia Cantiana. XI. London: Kent Archaeological Society: 49–112. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- Woodger, L.S. (1993). "Fogg, Sir Thomas (d.1407), of Repton in Ashford and Canterbury, Kent". In Roskell, J.S.; Clark, L.; Rawcliffe, C. (eds.). The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1386–1421. Boydell and Brewer.

External links

- Will of Thomas Fogge, proved 21 October 1512, PROB 11/17/267, National Archives Retrieved 23 September 2013

- The town and parish of Ashford, The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent: Volume 7 (1798), pp. 526–545 Retrieved 23 September 2013

- https://web.archive.org/web/20110710171822/http://edwardv1483.com/index.php?p=1_7_Richard-s-Rebels [unreliable source?]