Siphusauctum

| Siphusauctum Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

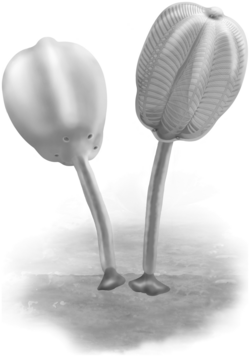

| Holotype of S. gregarium | |

| |

| Fossil of S. lloydguntheri | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Ctenophora |

| Stem group: | Ctenophora |

| Family: | †Siphusauctidae O'Brien & Caron, 2012 |

| Genus: | †Siphusauctum O'Brien & Caron, 2012 |

| Species | |

| |

Siphusauctum, also known as the tulip animal, is an extinct genus of filter-feeding animals that lived during the Middle Cambrian.

Description

Siphusauctum was a sessile animal that was attached to the substrate by a holdfast. It had a tulip-shaped body, called the calyx, into which it actively pumped water that entered through pores and filtered out and digested organic contents. It grew to a length of only about 20 cm (7.9 in).[1][2] It is suggested to have primarily consumed microplankton.[3]

Taxonomy

Species

Siphusauctum gregarium was described in 2012 from numerous fossils recovered from the "Tulip Beds" strata of the Burgess Shale of Yoho National Park, British Columbia, Canada. The generic name comes Latin siphus ("cup" or "goblet") and auctus ("large"), referring to the general shape and size of the animal. The specific epithet comes from Latin gregalis ("flock" or "herd") referring to the large numbers of specimens recovered.[1] This species is colloquially referred to as the "Tulip Animal" due to its similar shape to the flower, and this colloquial name is also where the Tulip Beds derived their name from, due to the abundance of Siphusauctum fossils found there.[1]

In 2017 a new species, Siphusauctum lloydguntheri, was reported from the Middle Cambrian Spence Shale of Utah.[2]

Affinity

In its original 2012 description, Siphusauctum was placed as the only member of the family Siphusauctidae, and suggested to have affinities with Bilateria, due to the suggestion that it possessed a digestive tract and anus, characteristic of the group.[1] However, later studies suggested that it was likely a member of the stem-group of Ctenophora (comb jellies) instead, due to sharing characteristic large cillia structures with the group. While living members of Ctenophora are typically free-living pelagic animals, other suggested members of the ctenophore stem-group, like Dinomischus, Daihua and Xianguangia are also sessile filter feeders.[4][3]

References

- ^ a b c d Lorna J. O'Brien & Jean-Bernard Caron (2012). "A new stalked filter-feeder from the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale, British Columbia, Canada". PLoS ONE. 7 (1) e29233. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...729233O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029233. PMC 3261148. PMID 22279532.

- ^ a b Julien Kimmig, Luke C. Strotz & Bruce S. Lieberman (2017). "The stalked filter feeder Siphusauctum lloydguntheri n. sp. from the middle Cambrian (Series 3, Stage 5) Spence Shale of Utah: its biological affinities and taphonomy". Journal of Paleontology. 91 (5): 902–910. Bibcode:2017JPal...91..902K. doi:10.1017/jpa.2017.57.

- ^ a b Zhao, Yang; Hou, Xian-guang; Cong, Pei-yun (2023-01-01). "Tentacular nature of the 'column' of the Cambrian diploblastic Xianguangia sinica". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 21 (1) 2215787. Bibcode:2023JSPal..2115787Z. doi:10.1080/14772019.2023.2215787. ISSN 1477-2019.

- ^ Zhao, Yang; Vinther, Jakob; Parry, Luke A.; Wei, Fan; Green, Emily; Pisani, Davide; Hou, Xianguang; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Cong, Peiyun (April 2019). "Cambrian Sessile, Suspension Feeding Stem-Group Ctenophores and Evolution of the Comb Jelly Body Plan". Current Biology. 29 (7): 1112–1125.e2. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.02.036. hdl:1983/40a6bcb8-a740-482c-a23c-7d563faea5c5. PMID 30905603.