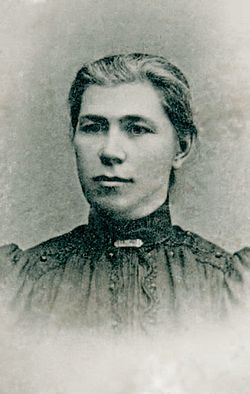

Maria Hrinchenko

Maria Mykolayivna Hrinchenko | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | Марія Миколаївна Грінченко |

| Born | Maria Gladilina 13 July 1863 |

| Died | 15 July 1928 (aged 65) |

| Pen name | Maria Zahirnia[1] |

| Occupation | Folklorist, teacher, writer |

| Spouse | Borys Hrinchenko |

Maria Mykolayivna Hrinchenko (Ukrainian: Марі́я Микола́ївна Грінче́нко, Russian: Мари́я Никола́евна Гринче́нко; 13 July 1863, Bohodukhiv – 15 July 1928)[2] was a Ukrainian folklorist and pedagogue active at the turn of the 20th century. She played a significant role in the preservation and development of Ukrainian folklore.[3][4] The four volume dictionary of the Ukrainian language she compiled with her husband, Borys Hrinchenko, is considered "one of the most important works in the history of the modern Ukrainian language."[3][5]

During her life, she collected and published more than 100 Ukrainian folk tales and over 1200 folk proverbs. She also authored research and memoirs on Opanas Markovych, Leonid Hlibov, Ivan Franko, and Borys Hrinchenko, among others.[2][4]

Biography

She was born in 1863 as Maria Gladilina near Bohodukhiv in the Kharkov Governorate,[2] a daughter of a minor official in the local government. Her family belonged to the merchant class,[1] and their status afforded Maria a good education; she studied history, literature and several foreign languages. Despite her family's Russian ancestry, starting from her youth Maria was an avid reader of Ukrainian literature, with Taras Shevchenko's Kobzar being among her favourite books. Her correspondence from the young years demonstrates her good knowledge of the Ukrainian language.[1]

Maria was a member of Kharkiv academy. Her last years at academy were considered as her most active ones. She met her lifelong friends and later correspondents during this part of her education life. She also became close to the new young principal during her last days in the academy. After leaving academy, she attended female seminary for a brief period of ten months, cut short most likely due to poor health.[citation needed]

Starting from 1881, Maria worked at a people's school in her native town.[1] In 1884 she married Borys Hrinchenko,[6] a fellow pedagogue whom she had met one year earlier while attending courses in Zmiiv. The couple's wedding ceremony took place in the village of Nyzhnia Syrovatka. Their only daughter Anastasia was born in the same locality in December 1884.[1]

In 1887 the family moved to Oleksiivka (modern-day Luhansk Oblast), where Borys and Maria taught at a private Ukrainian school established by Khrystyna Alchevska. During that period several of Maria's literary translations were published. However, in 1893 teaching of Ukrainian language in private schools was forbidden by authorities, and soon thereafter Borys was fired from his position, allegedly due to his support of Socialist ideas. In 1894 Maria moved to Chernihiv, where she was active in the local underground Ukrainian hromada. During that time she had close contacts with Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky and Sofia Rusova. In Chernihiv Maria engaged in the organization of the local museum, which was opened in 1902. It was even proposed to appoint her head the museum's manager, but this idea didn't find the support of the local governor.[1]

In 1901 Borys Hrinchenko was invited to Kyiv by the magazine Kievskaya starina in order to work on a dictionary of the Ukrainian language. Maria followed her husband. After her daughter Anastasia left to study philosophy in Lviv in 1903, Maria engaged into the work of various Ukrainian civic organization, including Prosvita, publishing books and organizing reading halls. During that period she continued publishing her own works.[1]

Between 1908 and 1910, Maria Hrinchenko lost her daughter, grandchild and husband. Her husband died of tuberculosis in 1910.[6] Despite the heavy loss, Maria continued her activities, establishing a publishing house. She continued to be associated with the Ukrainian intelligentsia, publishing works against repression of the Ukrainian language.[6] In 1917 she served as a member of the All-Ukrainian National Congress, and from 1919 was active in a commission of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, working on a Russian-Ukrainian dictionary. Between 1926 and 1927 she edited a 10-volume collection of works by her late husband.[1]

In her last years, much of her work was focused on a commission compiling a dictionary of the colloquial Ukrainian language.[6] She worked as an editor of her second dictionary together with Ahatanhel Krymsky.[1]

Maria Hrinchenko died suddenly in July 1928 after receiving a letter, in an environment just before the beginning of the 1929–1930 show trials persecuting Ukrainian intellectuals, including her associates.[6]

Work

Hrinchenko wrote her first works in German, beginning in 1880. Besides a proficiency in German she spoke Ukrainian as well as Polish. Taras Shevchenko and Ivan Franko were the main inspiration of her early poetry. It was associated with the poet's loneliness, social isolation and by an adoration of Ukrainian nation's freedom. Her first collection of poetry was published in 1898.

Between 1895 and 1899, Hrinchenko wrote a three volume collection of ethnographic materials from Chernihiv and surrounding areas.[6] In 1900, she wrote a collection of Ukrainian fables and folk tales entitled, "Из уст народа" (From the Mouths of the People).[6] In 1901, she wrote a book entitled, "Література украинского фолкльора" (Literature of Ukrainian Folklore).[6]

In 1906, Hrinchenko was a contributor to the Ukrainian daily newspaper, "Громадська думка" (Hromadska Dumka).[6]

Between 1907 and 1909, she and her husband, Borys, published a Ukrainian dictionary entitled, "Словарь української мови".[6]

Bibliography

Translations

- Black Sea Cossacks in Captivity (Чорноморці в неволі, 1889)

- Socrates, the Greek Teacher (Сократ, грецький учитель, 1893)

- The Good Soul (Добра душа, a translation of Alfred, Lord Tennyson, 1895)

Original works

- How Car Driving Was Invented (Як вигадано машиною їздить, 1896)

- Joan of Arc, Maid of Orleans (Орлеанська дівчина Жанна Д’Арк, 1897)

- A Good Advice (Добра порада, 1898)

- Under Sea Waves (Під морськими хвилями, 1901)

- Abraham Lincoln (Абрахам Лінкольн, 1901)

- The Struggle of England's American Colonies for Freedom (Боротьба англійських колоній американських за волю, 1905)

- Who is the People's Enemy? (Хто народові ворог?, 1905)

- Hetman Petro Sahaidachny (Гетьман Петро Сагайдачний, 1909)

- On Marriage in Ukraine during the Old Times (Про одружіння на Вкраїні в давніші часи, 1912)

- On State Institutions among All Peoples (Про державний лад у всіх народів, 1917)

- On Electoral Law (Про виборче право, 1917)[1]

Influences

In addition to Shevchenko and Franko, Hrinchenko's work was influenced by Henrik Ibsen, Edmondo De Amicis and Leo Tolstoy.[citation needed]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Марія Загірня — «тінь» генія чи окрема величина?". 2025-12-26. Retrieved 2026-01-04.

- ^ a b c "Hrinchenko, Mariia". www.encyclopediaofukraine.com. Retrieved 2023-07-20.

- ^ a b "Animals, Folk Tales and Tragedy: the family story behind a Ukrainian reading book". blogs.bl.uk. Retrieved 2023-07-20.

- ^ a b Альошина, Марина Дмитрівна (2013). "Modernizing trends in translation works by Borys Hrinchenko's family". Scientific Journal "Scientific Horizons" (in Ukrainian) (1): 38–43.[dead link]

- ^ "Головна сторінка Словника української мови за редакцією Грінченка | Словник української мови. Словник Грінченка". hrinchenko.com. Retrieved 2023-07-20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lashko, M.V. (July 20, 2023). "До 155 – річчя М. Грінченко" (PDF). Kyiv University named after B. Hrinchenko. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 20, 2023. Retrieved July 20, 2023.

External links

- Skrypnyk, P. Maria Hrinchenko (ГРІНЧЕНКО МАРІЯ МИКОЛАЇВНА). Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine. 2004