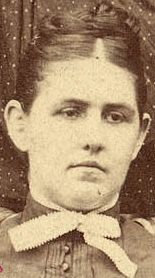

Anna Sarah Kugler

Anna Sarah Kugler | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | April 19, 1856 |

| Died | July 26, 1930 (aged 74) |

| Occupation | Medical Missionary in India |

| Known for | Founding a hospital in Guntur, India and teaching medicine |

Dr. Anna Sarah Kugler (19 April 1856 – 26 July 1930) was the first medical missionary of the Evangelical Lutheran General Synod of the United States of North America. She served in India for 47 years.[1] She founded a hospital in Guntur which was later named for her.

Early life and education

She was born in Ardmore, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, on April 19, 1856, to Charles Kugler and Harriet S. Sheaff.[2] She attended a private school in Bryn Mawr and graduated from Friends' Central High School in Philadelphia. She then attended the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania, graduating in 1879.[2] She interned for two years in the Women's Department of the Norristown State Hospital.[2]

Medical career

In 1882 she received a letter from the Reverend Adam D. Rowe, a Lutheran missionary serving in India, suggesting that India urgently needed medical missionaries to serve women.[3] She decided to apply for sponsorship to the Woman's Home and Foreign Missionary Society of the General Synod of the Lutheran Church in America. The Synod board said it was "not yet ready to undertake work of this kind" (i.e., medical mission) but was willing to send her to India as a teacher for Muslim women living in harems.[4] She accepted the assignment because she was sure she could eventually convince the board to establish medical work in India, and she wanted to be in at the beginning.[3] On August 25, 1883, she sailed for India, arriving on November 29, 1883. She was assigned to Guntur in the state of Andhra Pradesh.

In addition to her teaching duties, she practised medicine for the local women, who had previously received only primitive medical care. Her work was hampered by limitations of caste and race - as a white woman she was regarded as "unclean" by high-caste Hindus - but she said, "it was all in the way of opening up the path for those who came later."[5] Despite the restrictions, during her first year in Guntur she treated 185 patients at their homes, and 276 at the Zenana Home where she lived. Her motto was "Ourselves Your Servants for Jesus' Sake."[3]

She continued her teaching and was placed in charge of the Hindu Girls School and the Girls Boarding School.[3] In December 1885 she was finally appointed a medical missionary.[4] She immediately began planning for a hospital and a dispensary. From 1889 to 1891 she was back in the United States on furlough; she used the time to complete her postgraduate work and study hospital-building and equipment. When she returned to India she was able to purchase an 18-acre plot of land with the donations generated by the goodwill she had earned and also with help from her fellow missionaries who collected money for her.

A dispensary was opened on the land in February 1893, and later that year the cornerstone for the American Evangelical Lutheran Mission Hospital was laid. The hospital itself opened on June 23, 1897. It was a 50-bed hospital and was regarded as one of the best in India. Bhuyanga Rao Bahadur of Ellore, a local Raja, became a supporter of Dr. Kugler's work after she treated his wife and delivered their son, and he donated the "Rao Chinnamagari Satram" as a rest-house opposite the hospital, where Hindu families could stay while their relatives were being treated.

In 1895 she was finally released from other mission duties and was able to devote herself full-time to medical work. In addition to her duties at the dispensary and hospital, she worked to open dispensaries in other villages throughout South India; raised funds for a children's ward, maternity ward and operating room in the hospital; and did medical work in Rentachintala.

While on furlough in the United States in 1928, she wrote Guntur Mission Hospital, an autobiography intended as a guide to future medical missionaries.[6][7]

Colleagues and Collaborators

Dr. Kugler's pioneering work at the American Evangelical Lutheran Mission Hospital was built on a foundation of collaboration with remarkable colleagues who helped establish and sustain the institution's medical and educational programs throughout its formative decades. Together, this network of physicians, nurses, and medical educators created one of the most successful medical missions in colonial India.

Katherine Fahs

Katherine Fahs (also spelled Katharine Fahs; December 11, 1856 – February 13, 1942) was a visionary missionary nurse appointed by the General Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church who became the architect of medical education in Guntur. Working alongside Dr. Kugler, Fahs demonstrated remarkable foresight by establishing the hospital's nursing training program in 1899—a full eight years before the main hospital building even opened its doors. Initial planning for this program began as early as 1889, revealing a decade-long commitment to building sustainable healthcare infrastructure in the region.[8]

The nursing school Fahs founded addressed a critical and often overlooked need. By training both nurses and midwives, she created a pipeline of qualified healthcare workers specifically equipped to serve women and children in a region where deeply entrenched cultural barriers—particularly purdah practices among high-caste families—severely restricted access to medical care. The program's genius lay in its cultural intelligence: by training Indian women to care for Indian women, it circumvented social restrictions that would have made treatment by male or foreign practitioners impossible.

Kugler's 1928 autobiography acknowledges "Miss Fahs" as one of the essential staff members who contributed to the hospital's development, though this modest mention barely captures her transformative impact.[9] Archival photographs from the ELCA Archives provide compelling visual documentation of Fahs's hands-on approach to medical care and education. Images from 1899 show her providing direct patient care in the hospital's early days, while a particularly remarkable 1906 photograph captures her administering anesthesia as Dr. Kugler performs surgery—a powerful testament to their clinical partnership and professional trust.

Fahs's educational model proved transformative not just for Guntur, but for medical missions throughout India. By training Indian women to serve their own communities, she created a culturally sensitive and sustainable healthcare system that could reach populations previously beyond the reach of Western medicine. Her approach recognized that effective healthcare required more than medical expertise—it demanded cultural competence and community integration.[10]

Her legacy endures in brick and mortar: Kugler College of Nursing continues to operate on the historic hospital campus in Guntur today, more than 130 years after Fahs first envisioned it. The institution stands as a living monument to her belief that education, not charity, was the key to lasting change.

Dr. Mary Baer

Dr. Mary Baer (1863–1942) was a distinguished medical missionary who arrived in India in 1895, quickly establishing herself as one of Dr. Kugler's most trusted colleagues and strategic partners in expanding Lutheran medical work. Baer brought impressive credentials to the mission field, having earned both her M.D. and a Master of Arts degree in the United States—an unusual dual qualification that reflected both her intellectual breadth and her commitment to holistic mission work—before her appointment by the Board of Foreign Missions of the General Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church.

Dr. Baer's role extended far beyond routine medical care, encompassing leadership, administration, and strategic planning. During Dr. Kugler's periodic furloughs to the United States—essential breaks that prevented missionary burnout but could disrupt institutional continuity—Baer served as acting superintendent of the Guntur Mission Hospital. Her seamless leadership during these intervals ensured uninterrupted medical services for the women and children who had come to depend on the facility, demonstrating both her clinical competence and her administrative acumen.

In 1912, Dr. Baer undertook her most ambitious initiative by founding Baer Christian Hospital in Chirala, a coastal town in what is now Prakasam district.[11] This expansion represented a calculated strategy to extend quality medical services to underserved communities beyond Guntur's reach. The new institution focused heavily on maternal health and pediatric care, addressing the staggering rates of maternal and infant mortality that plagued the region. Dr. Baer's clinical expertise, combined with her deep understanding of local health challenges, made the hospital an immediate success.

Known for her extraordinary resilience and unwavering dedication, Baer remained in India for over four decades—a tenure that speaks to both her stamina and her genuine love for the communities she served. She became a deeply respected figure not just within the Lutheran mission network, but among the local population who came to see her as their own physician, not merely a foreign missionary. The hospital bearing her name continues to serve the region today, operating for more than a century as a lasting testament to her vision, clinical skill, and commitment to healthcare equity.

Dr. P. Paru

Dr. P. Paru represents one of the mission's greatest success stories—a pioneering Indian physician who joined the Guntur Mission Hospital staff in 1911 and became both Dr. Kugler's valued professional colleague and close personal friend. Her appointment marked a watershed moment in the mission's history, demonstrating an institutional commitment to integrating highly trained Indian women into senior medical positions rather than perpetuating a paternalistic, exclusively foreign-led model. In an era when few Indian women pursued medical education and even fewer achieved positions of significant responsibility, Dr. Paru's role carried profound symbolic and practical importance.

Dr. Kugler frequently praised Paru's clinical skill and unwavering dedication in both private correspondence and public writings, describing her as an indispensable partner in the hospital's daily operations and strategic planning.[12] Their professional partnership embodied the collaborative spirit that distinguished successful missions from failed ones, bridging cultural differences through shared commitment to healing, mutual respect, and genuine friendship. The relationship between Kugler and Paru demonstrated that effective mission work required partnership, not patronage.

After serving at Guntur with distinction for twelve years until 1923, Dr. Paru made the significant decision to return to her home on the Malabar Coast, where she established her own independent medical clinic. This move, far from representing a loss for the Guntur mission, exemplified what might be called the "multiplier effect"—the exponential expansion of impact that occurred when trained Indian practitioners established their own institutions. Dr. Paru's career trajectory embodied the mission's ultimate goal: creating indigenous healthcare leadership that could serve India's needs without perpetual dependence on foreign missionaries. Her success validated the educational investment made by Kugler and Fahs, proving that training and empowering local practitioners created far more sustainable change than maintaining foreign control.

Dr. Eleanor B. Wolf Stewart

Dr. Eleanor B. Wolf Stewart (B.A., M.D.) brought exceptional credentials and advanced surgical expertise to the mission as a graduate of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine—at the time, one of the world's premier medical institutions and a pioneer in modern medical education. She joined the Guntur staff during a period of rapid institutional growth in the early twentieth century, when the hospital was expanding both its physical infrastructure and its clinical capabilities.

Dr. Wolf Stewart quickly became renowned for her work in the operating theater, where her Johns Hopkins training allowed her to perform complex surgical procedures that had previously been impossible in the mission hospital setting. Her leadership proved crucial during the expansion of the hospital's inpatient capacity, as she helped design clinical protocols and train staff to manage the increased patient volume without compromising care quality.

Beyond her surgical expertise, Dr. Wolf Stewart championed the challenging and often dangerous work of "zenana" medical missions. This specialized outreach involved visiting women confined to the secluded domestic quarters of high-caste families—women who were culturally and sometimes physically prohibited from seeking care in public dispensaries. These home visits required not just medical skill but cultural sensitivity, patience, and often considerable negotiation with male family members who controlled access to female relatives. The work was exhausting and frequently frustrating, but it remained essential for reaching populations that would otherwise have no access to medical care whatsoever.

Working alongside Dr. Kugler, Wolf Stewart played a key role in professionalizing the hospital's administration during a critical period of institutional development. She helped ensure that the facility met rigorous standards set by both missionary boards in America and colonial medical authorities in India—a dual accountability that required careful navigation. Her contributions helped establish Guntur Mission Hospital's reputation for clinical excellence, making it a model for other medical missions throughout South Asia.

Other Staff and Assistants

The medical work in Guntur flourished through the contributions of numerous other dedicated professionals whose individual stories deserve fuller documentation:

Dr. Elsie R. Mitchell joined the mission in the early 1900s during a pivotal period of institutional expansion, providing essential medical support as the hospital grew from a small dispensary into a 50-bed facility capable of serving significantly more patients. Her arrival helped distribute the overwhelming clinical workload that had previously fallen on just one or two physicians. Dr. Mary Fleming provided essential support in the hospital's wards while also participating actively in community outreach efforts. She helped bring medical care beyond the hospital walls through village clinics and health education programs, recognizing that preventive care and public health education were as important as treating acute illness. Rebecca Hoffman Davies served as a missionary nurse, dedicating her considerable skills to the hospital's pediatric and maternity wards alongside Katherine Fahs. Her work with mothers and children addressed some of the region's most pressing health crises, particularly the devastating rates of infant and maternal mortality. Dr. D. Joshua, an Indian medical assistant, played a crucial role that extended far beyond his official clinical duties. He provided vital linguistic and cultural mediation for the local Telugu-speaking population, helping bridge the often substantial gap between foreign medical practitioners and the communities they sought to serve. His presence helped patients feel more comfortable and ensured that medical instructions were properly understood and followed—factors that significantly improved treatment outcomes.

Impact and Legacy

Collectively, these colleagues created something far greater than a hospital. They built an interconnected system of medical care, education, and indigenous leadership that transformed healthcare access across the region. The nursing school founded by Katherine Fahs, the satellite hospital established by Dr. Mary Baer, and the independent clinics opened by trained Indian physicians like Dr. P. Paru created a multiplier effect that extended the mission's impact far beyond what any single institution could achieve.

Their model of collaborative, culturally intelligent healthcare delivery offered an alternative to the paternalistic approaches that characterized many colonial-era medical missions. By prioritizing education over dependency, partnership over patronage, and indigenous leadership over permanent foreign control, they created institutions that could sustain themselves and evolve to meet changing community needs—institutions that continue serving their communities more than a century later.

Recognition

In recognition of her work she was twice (1905 and 1917) awarded the Kaisar-i-Hind Medal, an award of distinction bestowed on civilians of any nationality who rendered services to the British Raj.

She fell ill from exhaustion in 1925 and returned to the United States for two years to recuperate. She then returned to India to carry on her work despite having pernicious anemia. She died at her own hospital in Guntur on July 26, 1930. She was buried in Guntur though there is a memorial to her in the Saint Paul's Lutheran Cemetery in Ardmore, Pennsylvania.[13][14][15] Shortly before her death she is reported to have said to Dr. Ida Scudder, her colleague and close associate, "I would like to get well and work longer, for I would like to feel I had served India for fifty years, and I have served only forty-seven." After her death the hospital she had founded was renamed Kugler Hospital in her honor.

References

- ^ "7 influential Lutheran women". Living Lutheran. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ a b c Kurian, George Thomas; Lamport, Mark A. (2016). Encyclopedia of Christianity in the United States, Volume 5. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 1299. ISBN 978-1442244320.

- ^ a b c d "Anna Sarah Kugler". Lutheran Leaders Collection. ECLA Archives. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ a b "The way we were: 1886". The Lutheran. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ Kretzmann, Paul E. (1930). Glimpses of the Lives of Great Missionary Women. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House. p. 80.

- ^ Kugler, Anna Sarah (1928). Guntur Mission Hospital, Guntur, India. Women's Missionary Society, The United Lutheran Church in America.

- ^ Shavit, David (1990). The United States in Asia: A Historical Dictionary. New York: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 288. ISBN 031326788X.

- ^ Kugler, Anna Sarah (1928). Guntur Mission Hospital, Guntur, India. Women's Missionary Society of the United Lutheran Church in America. p. 135.

- ^ Kugler, Anna Sarah (1928). Guntur Mission Hospital, Guntur, India. Women's Missionary Society of the United Lutheran Church in America.

- ^ Singh, Maina Chawla (2005). "Women, Mission, and Medicine: Clara Swain, Anna Kugler, and Early Medical Endeavors in Colonial India". International Bulletin of Missionary Research. 29 (3): 128–133. doi:10.1177/239693930502900304.

- ^ Kugler, Anna Sarah (1928). Guntur Mission Hospital, Guntur, India. Women's Missionary Society of the United Lutheran Church in America.

- ^ Kugler, Anna Sarah (1928). Guntur Mission Hospital, Guntur, India. Women's Missionary Society of the United Lutheran Church in America. p. 142.

- ^ "Dr Anna Sarah Kugler". Find a Grave Memorial. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ "Dr Anna Sarah Kugler Memorial". Lower Merion History. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ^ "Anna S. Kugler, M.D. Guntur Medical Mission Hospital".

Further reading

- Lindley, Susan Hill; Stebner, Eleanor J., eds. (2008). The Westminster Handbook to Women in American Religious History. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 124.

- Elizabeth, Eva Sundari (2017). The Life and Work of Dr. Anna Sarah Kugler.