| Part of a series on |

| War (outline) |

|---|

|

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, including recruited children, use ambushes, sabotage, terrorism, raids, petty warfare or hit-and-run tactics in a rebellion, in a violent conflict, in a war or in a civil war to fight against regular military, police or rival insurgent forces.[1]

Although the term "guerrilla warfare" was coined in the context of the Peninsular War in the 19th century,[2] the tactical methods of guerrilla warfare have long been in use. In the 6th century BC, Sun Tzu proposed the use of guerrilla-style tactics in The Art of War. The 3rd century BC Roman general Quintus Fabius Maximus Verrucosus is also credited with inventing many of the tactics of guerrilla warfare through what is today called the Fabian strategy, and in China Peng Yue is also often regarded as the inventor of guerrilla warfare. Guerrilla warfare has been used by various factions throughout history and is particularly associated with revolutionary movements and popular resistance against invading or occupying armies.

Guerrilla tactics focus on avoiding head-on confrontations with enemy armies, typically due to inferior arms or forces, and instead engage in limited skirmishes with the goal of exhausting adversaries and forcing them to withdraw (see also attrition warfare). Organized guerrilla groups often depend on the support of either the local population or foreign backers who sympathize with the guerrilla group's efforts.

Etymology

The Spanish word guerrilla is the diminutive form of guerra ("war"); hence, "little war". The term became popular during the early-19th century Peninsular War, when, after the defeat of their regular armies, the Spanish and Portuguese people successfully rose against the Napoleonic troops and defeated a highly superior army using the guerrilla strategy in combination with a scorched earth policy and people's war (see also attrition warfare against Napoleon). In correct Spanish usage, a person who is a member of a guerrilla unit is a guerrillero ([geriˈʎeɾo]) if male, or a guerrillera ([geriˈʎeɾa]) if female. Arthur Wellesley adopted the term "guerrilla" into English from Spanish usage in 1809,[2] to refer to the individual fighters (e.g., "I have recommended to set the Guerrillas to work"), and also (as in Spanish) to denote a group or band of such fighters. However, in most languages guerrilla still denotes a specific style of warfare. The use of the diminutive evokes the differences in number, scale, and scope between the guerrilla army and the formal, professional army of the state.[3]

History

Prehistoric tribal warriors presumably employed guerrilla-style tactics against enemy tribes:

Primitive (and guerrilla) warfare consists of war stripped to its essentials: the murder of enemies; the theft or destruction of their sustenance, wealth, and essential resources; and the inducement in them of insecurity and terror. It conducts the basic business of war without recourse to ponderous formations or equipment, complicated maneuvers, strict chains of command, calculated strategies, timetables, or other civilized embellishments.[4]

Evidence of conventional warfare, on the other hand, did not emerge until 3100 BC in Egypt and Mesopotamia. The Chinese general and strategist Sun Tzu, in his The Art of War (6th century BC), became one of the earliest to propose the use of guerrilla warfare.[5] This inspired developments in modern guerrilla warfare.[6]

In the 3rd century BC, Quintus Fabius Maximus Verrucosus, used elements of guerrilla warfare, such as the evasion of battle, the attempt to wear down the enemy, to attack small detachments in an ambush[7] and devised the Fabian strategy, which the Roman Republic used to great effect against Hannibal's army, see also His Excellency : George Washington: the Fabian choice.[8] The Roman general Quintus Sertorius is also noted for his skillful use of guerrilla warfare during his revolt against the Roman Senate. In China, Han dynasty general Peng Yue is often regarded as the inventor of guerrilla warfare due to his use of irregular warfare in the Chu-Han contention to attack Chu convoys and supplies.[9][10]

In the Byzantine Empire, guerrilla warfare was frequently practiced between the eighth through tenth centuries along the eastern frontier with the Umayyad and then Abbasid caliphates. Tactics involved a heavy emphasis on reconnaissance and intelligence, shadowing the enemy, evacuating threatened population centres, and attacking when the enemy dispersed to raid.[11] In the later tenth century this form of warfare was codified in a military manual known by its later Latin name as De velitatione bellica ('On Skirmishing') so it would not be forgotten in the future.[12]

The Normans often made many forays into Wales, where the Welsh used the mountainous region, which the Normans were unfamiliar with, to spring surprise attacks upon them.[13]

Since the Enlightenment, ideologies such as nationalism, liberalism, socialism, and religious fundamentalism have played an important role in shaping insurgencies and guerrilla warfare.[14]

In the 17th century, Chatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, founder of the Maratha Kingdom, pioneered the Shiva sutra or Ganimi Kava (Guerrilla Tactics) to defeat the many times larger and more powerful armies of the Mughal Empire.[15]

Kerala Varma (Pazhassi Raja) (1753–1805) used guerrilla techniques chiefly centred in mountain forests in the Cotiote War against the British East India Company in India between 1793 and 1806. Arthur Wellesley (in India 1797–1805) had commanded forces assigned to defeat Pazhassi's techniques but failed. It was the longest war waged by East India Company during their military campaigns on the Indian subcontinent. It was one of the bloodiest and hardest wars waged by East India Company in India with Presidency army regiments that suffered losses as high as eighty percent in 10 years of warfare.[16]

The Dominican Restoration War was a guerrilla war between 1863 and 1865 in the Dominican Republic between nationalists and Spain, the latter of which had recolonized the country 17 years after its independence. The war resulted in the withdrawal of Spanish forces and the establishment of a second republic in the Dominican Republic.[17]

The Moroccan military leader Abd el-Krim (c. 1883 – 1963) and his father[18] unified the Moroccan tribes under their control and took up arms against the Spanish and French occupiers during the Rif War in 1920. For the first time in history, tunnel warfare was used alongside modern guerrilla tactics, which caused considerable damage to both the colonial armies in Morocco.[19]

In the early 20th century Michael Collins and Tom Barry both developed many tactical features of guerrilla warfare during the guerrilla phase of the 1919–1921 Irish War of Independence. Collins developed mainly urban guerrilla warfare tactics in Dublin City (the Irish capital). Operations in which small Irish Republican Army (IRA) units (3 to 6 guerrillas) quickly attacked a target and then disappeared into civilian crowds frustrated the British enemy. The best example of this occurred on Bloody Sunday (21 November 1920), when Collins's assassination unit, known as "The Squad", wiped out a group of British intelligence agents ("the Cairo Gang") early in the morning (14 were killed, six were wounded) – some regular officers were also killed in the purge. That afternoon, the Royal Irish Constabulary force consisting of both regular RIC personnel and the Auxiliary Division took revenge, shooting into a crowd at a football match in Croke Park, killing fourteen civilians and injuring 60 others.[20][21]

In West County Cork, Tom Barry was the commander of the IRA West Cork brigade. Fighting in west Cork was rural, and the IRA fought in much larger units than their fellows in urban areas. These units, called "flying columns",[22] engaged British forces in large battles, usually for between 10 – 30 minutes. The Kilmichael Ambush in November 1920 and the Crossbarry Ambush in March 1921 are the most famous examples of Barry's flying columns causing large casualties to enemy forces.

The Algerian Revolution of 1954 started with a handful of Algerian guerrillas. Primitively armed, the guerrillas fought the French for over eight years. This remains a prototype for modern insurgency and counterinsurgency, terrorism, torture, and asymmetric warfare prevalent throughout the world today.[23] In South Africa, African National Congress (ANC) members studied the Algerian War, prior to the release and apotheosis of Nelson Mandela;[24] in their intifada against Israel, Palestinian fighters have sought to emulate it.[25] Additionally, the tactics of Al-Qaeda closely resemble those of the Algerians.[26]

The Mukti Bahini (Bengali: মুক্তিবাহিনী, translates as "freedom fighters", or liberation army), also known as the Bangladesh Forces, was the guerrilla resistance movement consisting of the Bangladeshi military, paramilitary and civilians during the Bangladesh Liberation War that transformed East Pakistan into Bangladesh in 1971. An earlier name Mukti Fauj was also used.

Theoretical works

The growth of guerrilla warfare was inspired in part by theoretical works on guerrilla warfare, starting with the Manual de Guerra de Guerrillas by Matías Ramón Mella written in the 19th century:

...our troops should...fight while protected by the terrain...using small, mobile guerrilla units to exhaust the enemy...denying them rest so that they only control the terrain under their feet.[27]

More recently, Mao Zedong's On Guerrilla Warfare,[28] Che Guevara's Guerrilla Warfare,[29] and Lenin's Guerrilla warfare,[30] were all written after the successful revolutions carried out by them in China, Cuba and Russia, respectively. Those texts characterized the tactic of guerrilla warfare as, according to Che Guevara's text, being "used by the side which is supported by a majority but which possesses a much smaller number of arms for use in defense against oppression".[31]

Foco theory

Why does the guerrilla fighter fight? We must come to the inevitable conclusion that the guerrilla fighter is a social reformer, that he takes up arms responding to the angry protest of the people against their oppressors, and that he fights in order to change the social system that keeps all his unarmed brothers in ignominy and misery.

In the 1960s, the Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara developed the foco (Spanish: foquismo) theory of revolution in his book Guerrilla Warfare,[33] based on his experiences during the 1959 Cuban Revolution. This theory was later formalized as "focal-ism" by Régis Debray. Its central principle is that vanguardism by cadres of small, fast-moving paramilitary groups can provide a focus for popular discontent against a sitting regime, and thereby lead a general insurrection. Although the original approach was to mobilize and launch attacks from rural areas, many foco ideas were adapted into urban guerrilla warfare movements.

Strategy, tactics and methods

Strategy

Guerrilla warfare is a type of asymmetric warfare: competition between opponents of unequal strength.[34] It is also a type of irregular warfare: that is, it aims not simply to defeat an invading enemy, but to win popular support and political influence, to the enemy's cost. Accordingly, guerrilla strategy aims to magnify the impact of a small, mobile force on a larger, more cumbersome one.[35] If successful, guerrillas weaken their enemy by attrition, eventually forcing them to withdraw.

Tactics

Tactically, guerrillas usually avoid confrontation with large units and formations of enemy troops but seek and attack small groups of enemy personnel and resources to gradually deplete the opposing force while minimizing their own losses. The guerrilla prizes mobility, secrecy, and surprise, organizing in small units and taking advantage of terrain that is difficult for larger units to use. For example, Mao Zedong summarized basic guerrilla tactics at the beginning of the Chinese Civil War as:

"The enemy advances, we retreat; the enemy camps, we harass; the enemy tires, we attack; the enemy retreats, we pursue."[36]

At least one author credits the ancient Chinese work The Art of War with inspiring Mao's tactics.[37] In the 20th century, other communist leaders, including North Vietnamese Ho Chi Minh, often used and developed guerrilla warfare tactics, which provided a model for their use elsewhere, leading to the Cuban "foco" theory and the anti-Soviet Mujahadeen in Afghanistan.[38]

Unconventional methods

Guerrilla groups may use improvised explosive devices and logistical support by the local population. The opposing army may come at last to suspect all civilians as potential guerrilla backers. The guerrillas might get political support from foreign backers and many guerrilla groups are adept at public persuasion through propaganda and use of force.[39] Some guerrilla movements today also rely heavily on children as combatants, scouts, porters, spies, informants, and in other roles.[40] Many governments and states also recruit children within their armed forces.[41][42]

Comparison of guerrilla warfare and terrorism

No commonly accepted definition of "terrorism" has attained clear consensus.[43][44][45] The term "terrorism" is often used as political propaganda by belligerents (most often by governments in power) to denounce opponents whose status as terrorists is disputed.[46][47]

While the primary concern of guerrillas is the enemy's active military units, actual terrorists largely are concerned with non-military agents and target mostly civilians.[48]

Weapons of guerrilla warfare

Due to the fluid nature of irregular warfare, the weapons of guerrillas vary widely and reflect on the resources available to the unconventional force.

Molotov cocktail

The Molotov cocktail is a generic name used for a variety of improvised incendiary weapons. Due to the relative ease of production, they are frequently used by amateur protesters and non-professionally equipped fighters in urban guerrilla warfares. They are primarily intended to set targets ablaze rather than instantly destroy them. A Molotov cocktail is a breakable glass bottle containing a flammable substance such as gasoline/petrol or a napalm-like mixture, with some motor oil added, and usually a source of ignition such as a burning cloth wick held in place by the bottle's stopper. The wick is usually soaked in alcohol or kerosene, rather than gasoline.

Improvised explosive devices

An improvised explosive device (IED), also known as a roadside bomb, is a homemade bomb constructed and deployed in ways other than in conventional military action. It may be constructed of conventional military explosives, such as an artillery round, attached to a detonating mechanism. IEDs may be used in terrorist actions or in unconventional warfare by guerrillas or commando forces in a theater of operations. In the second Iraq War, IEDs were used extensively against US-led Coalition forces and by the end of 2007 they had become responsible for approximately 63% of Coalition deaths in Iraq. They were also used in Afghanistan by insurgent groups, and caused over 66% of the Coalition casualties in the 2001–2021 Afghanistan War.[49]

Throughout The Troubles, the Provisional IRA made extensive use of remote control IEDs against the British security forces. Initially, bombs were detonated either by timer or by simple command wire, but later in the conflict, bombs could be detonated by radio control; simple servos from radio-controlled aircraft were used to close the electrical circuit and supply power to the detonator. Roadside bombs were also extensively used; they were typically placed in a drain or culvert along a rural road and detonated by remote control when British security forces vehicles were passing. The IRA also used secondary devices to attack British reinforcements sent in after an initial blast as occurred in the Warrenpoint Ambush. IRA bombs became highly sophisticated, featuring anti-handling devices such as a mercury tilt switch or microswitches. These devices would detonate the bomb if it was moved in any way. Typically, the safety-arming device used was a clockwork Memopark timer, which armed the bomb up to 60 minutes after it was placed by completing an electrical circuit supplying power to the anti-handling device. Depending on the particular design, an independent electrical circuit supplied power to a conventional timer set for the intended time delay, e.g. 40 minutes. However, some electronic delays developed by IRA technicians could be set to accurately detonate a bomb weeks after it was hidden. After the British developed jammers, IRA technicians also developed devices that required a sequence of pulsed radio codes to arm and detonate them that were harder to jam.

Starting six months before the invasion of Afghanistan by the USSR on 27 December 1979, the Afghan mujahideen were supplied by the CIA, among others, with large quantities of many different types of anti-tank mines. The insurgents often removed the explosives from several anti-tank mines and combined the explosives in a tin cooking-oil can in order to ensure that a target vehicle would be destroyed.[50] By combining the explosives from several mines and placing them in tin cans, the insurgents made them more powerful, but sometimes also easier to detect by Soviet sappers using mine detectors. After an IED was detonated, the insurgents often used direct-fire weapons such as machine guns and rocket-propelled grenades to initiate an ambush. Afghan insurgents also made IEDs from Soviet unexploded ordnance, such as 250-500 kg (500-1000) aerial bombs.[50] The devices were triggered by a variety of methods, including remote control, pressure plates (some designed to detonate only after several vehicles drove over them), tripwires, pressure-release plates held down by roadblocks, and electrical cables that triggered only when the metal tracks of a tank or BMP drove over them;[51] these devices were hidden under roads and mountain passes and inside water wells, abandoned caves and buildings.[51] The Soviets responded by issuing soldiers with flak jackets, reinforcing and sandbagging the floors of their vehicles, and riding on top of vehicles instead of inside them,[51] but casualties remained high, with 1,995 Soviet soldiers and 1,191 vehicles lost to mines and IEDs during the Soviet-Afghan War.[52]

During the First and Second Chechen Wars, the separatist Chechen Republic of Ichkeria made use of IEDs extensively against the Russian Armed Forces once they were forced to rely on guerrilla tactics, constructing them from a variety of materials such as 155mm artillery shells, 82mm mortar shells, unexploded ordnance and industrial explosives.[53] These devices were usually command-detonated using an electrical command wire and hidden in sewer lines, piles of trash, destroyed vehicles, or placed directly on or under the surface or shoulder of a road, as well in trees or hillsides.[54] Sometimes, insurgents combined antitank with antipersonnel devices, with one charge to target a vehicle, the other to target infantry dismounting from the vehicle.[54] For propaganda purposes, IED teams often had a cameraman whose job was to record IED attacks and post it online.[53]

Since the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan, the Taliban and its supporters have used IEDs against NATO and Afghan military and civilian vehicles. This has become the most common method of attack against NATO forces, with IED attacks increasing consistently year on year; according to a report by the Homeland Security Market Research in the US, the number of IEDs used in Afghanistan had increased by 400 percent since 2007 and the number of troops killed by them by 400 percent, and those wounded by 700 percent. It has been reported that IEDs are the number one cause of death among NATO troops in Afghanistan.

Beginning in July 2003, the Iraqi insurgency used IEDs to target invading coalition vehicles. Many of these IEDs were made from military explosives looted from munitions bunkers following the 2003 invasion, such as landmines stripped of their explosives, 155-millimetre artillery shells rigged with blasting caps and modified aviation bombs of 500 lb or more, detonated by systems such as pull-wires and mechanical detonators, cell-phones, garage-door openers, cables, radio control (RC), and infrared lasers among others. To counter increasing armor protection, the insurgents have also developed IEDs that make use of explosively formed projectiles (EFPs); these are essentially cylindrical shaped charges usually constructed with a machined concave metal disc (often copper) facing the target, pointed inward. The force of the shaped charge turns the disc into a high velocity slug, capable of penetrating the armor of most enemy vehicles. Commonly positions for IEDs include on utility poles, road signs or trees, buried underground or in piles of garbage, disguised as rocks or bricks, and even inside dead animals. Typically they explode underneath or to the side of the vehicle, however, IEDs in elevated positions such as on road signs are able hit less protected areas. It has been estimated by the Washington Post that as much as 64% of U.S. deaths in Iraq occurred due to IEDs.

IEDs have also been used extensively by other groups, such as Maoists in India,[55] ISIL in Syria and across the world, and by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in Sri Lanka.[56][57]

Acquiring conventional weapons

Captured enemy weapons

Insurgencies have long made use of weapons stolen, captured or otherwise procured from enemy forces due to the ease of procuring them and their ammunition, something that is very important to an insurgency which will be poorly equipped and will need whatever weaponry it can get. Such weapons are typically acquired by either looting them from enemy soldiers that they have defeated, by having infiltrators and sympathisers in the enemy forces steal munitions and secretly supply it to them, by gathering munitions abandoned by retreating, advancing or neglectful enemy soldiers, or by purchasing munitions sold by enemy soldiers on the black market.

During World War II, firearms captured from the Axis powers were used extensively by resistance movements in Europe and the Pacific, due to their availability. These weapons were used alongside weapons supplied by the Allies and weapons inherited from their countries' previous militaries. Methods of acquiring weapons included purchasing them on the black market from Axis soldiers or their allies or stealing from German supply depots or transports.[58] Special efforts were also made to capture weapons from the Axis, such as raids were conducted on trains and vehicles carrying equipment to the front, as well as on guardhouses and gendarmerie posts, that proved highly successful. Sometimes weapons were taken from individual Axis soldiers accosted in streets or were brought over by defecting Axis collaborators. During the Warsaw Uprising, the Polish Armia Krajowa (AK, Home Army) even managed to capture several German armored vehicles, most notably a Jagdpanzer 38 Hetzer light tank destroyer renamed "Chwat" and an Sd.Kfz. 251 armoured personnel carrier renamed "Grey Wolf".[59] Captured German weapons used by European resistance groups included the Karabiner 98k bolt-action rifle and MP 40 submachine gun, while resistance groups in the Pacific used captured Japanese weapons such as the Nambu pistol and Arisaka bolt-action rifle.

During the First Indochina War, the Indochinese Viet Minh used weapons abandoned by or captured from the Japanese during WWII, but also made use of weapons captured from the French and their French Indochina administration, such as the MAS-36 and MAS-49 rifles, MAT-49 submachine gun and the FM 24/29, Reibel, Vickers and Hotchkiss M1914, M1922 and M1929 machine guns.

Japanese and French weapons continued to see service with the Liberation Army of South Vietnam of the Viet Cong during the Vietnam War, with regular units using them during the early stages of the war, before they were passed down to militia units. They also used U.S-made weapons captured from the South Vietnamese Army of the Republic of Vietnam, such as M1911 pistols, Thompson and M3 submachine guns, M1 Garand rifles, M1 and M2 carbines and M1918 BAR and M1919 Browning machine guns, which they either captured in ambushes or raids or purchased off of the black market, the latter case being made possible by corrupt ARVN military officers illegally selling munitions for profit. Later in the war following the U.S intervention, more modern U.S weapons such as M14 and M16 rifles, M60 and M2 Browning machine guns and M79 grenade launchers were captured from U.S forces and the increasingly modernised ARVN.

Plausible deniability and sanitized arms

Plausible deniability allows the supply of arms by governments to insurgents without the need for over elaborate ruses. For instance, the sheer number of AKM (an upgraded version of the AK-47 rifle) manufacturers and users in the world means that governments can supply these weapons to insurgents with plausible deniability as to exactly from where and from whom the guns were acquired. The governments of nations with self-sufficient arms industries may intentionally remove identifying marks of their weapons for this purpose. For example, the Yugoslavian Zastava M48BO (for bez oznake, 'without markings') rifle was manufactured with no markings save for a serial number. These were made in Yugoslavia for delivery to Egypt prior to the Suez Crisis of 1956. Yugoslavia was technically a neutral country, and by sanitizing the rifles sold to the Egyptians, it hoped to distance itself from the conflict between Egypt and Israel. Only a few hundred of the few thousand made were delivered to Egypt, the rest remaining in storage in Yugoslavia until recently rediscovered. They are currently being sold to civilian collectors.[60] [61]

Soviet Bloc weaponry

Due to the massive exportation of weaponry by the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc to communist governments and insurgencies in foreign countries, as well as the production of Soviet-made weaponry by many militaries around the world, Soviet-made weapons and their copies are widely available, being present in most Third World countries throughout Asia, Africa and the Middle East. Of particular notability is the AK-47 assault rifle and its AKM variant which have seen service in almost every conflict since the Korean War in the militaries of Third World countries and insurgent groups due to its wide availability, simplicity, reliability, durability and ease of use, however they are just two of countless other types of Soviet World War II-era weapons, such as the TT pistol, Mosin–Nagant bolt-action rifle, PPSh-41 submachine gun, RPD and SG-43 Goryunov medium machine guns and DShK heavy machine gun, and Cold War-era weapons such as the AK-74 assault rifle, RPK light machine gun, PK general-purpose machine gun, SVD-63 Dragunov sniper rifle and RPG-2 and RPG-7 rocket launchers.

The first large-scale usage by an insurgency of the Kalashnikov series weapons was during the Vietnam War, when massive numbers of Soviet, Chinese and Eastern Bloc-produced AKs and RPKs, along with limited numbers of PKs and SVD-63s, were provided by communist countries to North Vietnam, which supplied them to the South Vietnamese Viet Cong, Laotian Pathet Lao and Cambodian Khmer Rouge. Due to the massive numbers of weapons that were supplied, they became the primary weapons of these groups and of the North Vietnamese army, replacing World War II-era French and Soviet-produced bolt-action rifles and submachine guns and supplanting weapons captured from U.S and South Vietnamese forces.

Rocket-propelled grenades

Rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs) were used extensively during the Vietnam War (by the Vietnam People's Army and Viet Cong),[62] Soviet invasion of Afghanistan by the Mujahideen and against South Africans in Angola and Namibia (formerly South West Africa) by SWAPO guerrillas during what the South Africans called the South African Border War. Twenty years later, they are still being used widely in recent conflict areas such as Chechnya, Iraq, and Sri Lanka.

The RPG still remains a potent threat to armored vehicles, especially in situations such as urban warfare or jungle warfare, where they are favored by guerrillas. They are most effective when used in restricted terrain as the availability of cover and concealment can make it difficult for the intended target to spot the RPG operator. Note that this concealment is often preferably outdoors, because firing an RPG within an enclosed area may create a dangerous backblast.

In Afghanistan, Mujahideen guerrilla fighters used RPG-7s to destroy Soviet vehicles. To assure a kill, two to four RPG shooters would be assigned to each vehicle. Each armored-vehicle hunter-killer team could have had as many as 15 RPGs per unit.[63] In areas where vehicles were confined to a single path (a mountain road, swamps, snow, urban areas), RPG teams trapped convoys by destroying the first and last vehicles in line, preventing movement of the other vehicles. This tactic was especially effective in cities. Convoys learned to avoid approaches with overhangs and to send infantrymen forward in hazardous areas to detect the RPG teams. Multiple shooters were also effective against heavy tanks with reactive armor: The first shot would be against the driver's viewing prisms. Following shots would be in pairs, one to set off the reactive armor, the second to penetrate the tank's armor. Favored weak spots were the top and rear of the turret.[64][65]

The Mujahideen sometimes used RPG-7s at extreme range, exploded by their 4.5-second self-destruct timer, which translates to roughly 950m flight distance, as a method of long distance approach denial for enemy infantry and reconnaissance.[66]

In the period following the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the RPG became a favorite weapon of the insurgent forces fighting U.S. troops. Since most of the readily available RPG-7 rounds cannot penetrate M1 Abrams tank armor from almost any angle, it is primarily effective against soft-skinned or lightly armored vehicles, and infantry. Even if the RPG hit does not completely disable the tank or kill the crew, it can still damage external equipment, lowering the tank's effectiveness or forcing the crew to abandon and destroy it. Newer RPG-7 rounds are more capable, and in August 2006, an RPG-29 round penetrated the frontal ERA of a Challenger 2 tank during an engagement in al-Amarah, Iraq, and wounded several crew members.[67]

During the South African Border War, the Soviet RPGs used by SWAPO guerrillas and their Angolan supporters posed a serious threat to South Africa's lightly armored APCs, which could be easily targeted as soon as they stopped to disembark troops. During the First (1994–1996) and Second Chechen Wars (1999–2009), Chechen rebels used RPGs to attack Russian tanks from basements and high rooftops. This tactic was effective because tank main guns could not be depressed or raised far enough to return fire, in addition, armor on the very top and bottom of tanks was usually the weakest. Russian forces had to rely on artillery suppression, good crew gunners and infantry screens to prevent such attacks. Tank columns were eventually protected by attached self-propelled anti-aircraft guns (ZSU-23-4 Shilka, 9K22 Tunguska) used in the ground role to suppress and destroy Chechen ambushes. Chechen fighters formed independent "cells" that worked together to destroy a specific Russian armored target. Each cell contained small arms and some form of RPG (RPG-7V or RPG-18, for example). The small arms were used to button the tank up and keep any infantry occupied, while the RPG gunner struck at the tank. While doing so, other teams would attempt to fire at the target in order to overwhelm the Russians' ability to effectively counter the attack. To further increase the chance of success, the teams took up positions at different elevations where possible. Firing from the third and higher floors allowed good shots at the weakest armor (the top).[68] When the Russians began moving in tanks fitted with explosive reactive armor (ERA), the Chechens had to adapt their tactics, because the RPGs they had access to were unlikely to result in the destruction of the tank.

Using RPGs as improvised anti-aircraft batteries has proved successful in Somalia, Afghanistan and Chechnya. Helicopters are typically ambushed as they land, take off or hover. In Afghanistan, the Mujahideen often modified RPGs for use against Soviet helicopters by adding a curved pipe to the rear of the launcher tube, which diverted the backblast, allowing the RPG to be fired upward at aircraft from a prone position. This made the operator less visible prior to firing and decreased the risk of injury from hot exhaust gases. The Mujahideen also utilized the 4.5-second timer on RPG rounds to make the weapon function as part of a flak battery, using multiple launchers to increase hit probabilities.[66] At the time, Soviet helicopters countered the threat from RPGs at landing zones by first clearing them with anti-personnel saturation fire. The Soviets also varied the number of accompanying helicopters (two or three) in an effort to upset Afghan force estimations and preparation. In response, the Mujahideen prepared dug-in firing positions with top cover, and again, Soviet forces altered their tactics by using air-dropped thermobaric fuel-air bombs on such landing zones. As the U.S.-supplied Stinger surface-to-air missiles became available to them, the Afghans abandoned RPG attacks as the smart missiles proved especially efficient in the destruction of unarmed Soviet transport helicopters, such as Mil Mi-17. In Somalia, both of the UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters lost by U.S. forces during the Battle of Mogadishu in 1993 were downed by RPG-7s.

Homemade or improvised firearms

The Błyskawica (Lightning) was a simple submachine gun produced by the Armia Krajowa, or Home Army, a Polish resistance movement fighting the Germans in occupied Poland. It was produced in underground workshops. Its main feature was its simplicity, so that the weapon could be made even in small workshops, by inexperienced engineers. It used threaded pipes for simplicity.

In some cases, guerrillas have used improvised, repurposed firearms. One example is described by Che Guevara in his book Guerrilla Warfare. Called the "M-16", it consists of a 16 gauge sawed-off shotgun provided with a bipod to hold the barrel at a 45-degree angle. This was loaded with a blank cartridge formed by removing the shot from a standard shot shell, followed by a wooden rod with a Molotov cocktail attached to the front. This formed an improvised mortar capable of firing the incendiary device accurately out to a range of 100 meters.[69]

Flare guns have also been converted to firearms. This may be accomplished by replacing the (often plastic) barrel of the flare gun with a metal pipe strong enough to chamber a shotgun shell, or by inserting a smaller bore barrel into the existing barrel (such as with a caliber conversion sleeve) to chamber a firearm cartridge, such as a .22 Long Rifle.[70][71]

Purpose-designed weapons

A fairly recent class of firearms, purpose-designed insurgency weapons first appeared during World War II, in the form of such arms as the FP-45 Liberator and the Sten submachine gun. Designed to be inexpensive, since they were to be airdropped or smuggled behind enemy lines, insurgency weapons were designed for use by guerrilla and insurgent groups. Most insurgency weapons are of simple design, typically made of sheet steel stampings, which are then folded into shape and welded. Tubular steel in standard sizes is also used when possible, and barrels (one of the few firearm parts that require fine tolerances and high strength) may be rifled (like the Sten) or left smoothbore (like the FP-45).

The CIA Deer gun of the 1960s was similar to the Liberator, but used an aluminum casting for the body of the pistol, and was chambered in 9×19 mm Parabellum, one of the all-time most common handgun cartridges in the world. There is no known explanation for the name "Deer Gun", but the Deer Gun was intended to be smuggled into Vietnam, attested by the instruction sheet printed in Vietnamese. It was produced by the American Machine & Foundry Co., but was a sanitized weapon, meaning it lacked any marking identifying manufacturer or user. Details of the manufacture of insurgency weapons are almost always deliberately obscured by the governments making them, as in the designation of the FP-45 pistol.

Other insurgency weapons may be sanitized versions of traditional infantry or defensive weapons. These may be purpose-made without markings, or they may be standard commercial or military arms that have been altered to remove the manufacturers markings. Due to the covert nature of insurgency weapons, documenting their history is often difficult. Those that can legally be traded on the civilian market, like the Liberator pistol, will often command high prices; although millions of the pistols were made, few survived the war.

These examples are all arms that were either used as insurgency weapons or designed for such use. Purpose-built weapons were designed from the start to be used primarily for insurgent use, and are fairly crude, very inexpensive, and simple to operate; many were packaged with instructions targeted to speakers of certain languages, or pictorial instructions usable by illiterate users or speakers of any language. Dual-use weapons are those that were designed with special allowances for use by insurgent troops. Sanitized weapons are any arms that have been manufactured or altered to remove markings that indicate the point of origin. IEDs are improvised explosive devices.

The FP-45 Liberator was a single-shot .45 ACP derringer-type pistol, made by the U.S. during World War II. It was made from stamped steel with an unrifled barrel. The designation "FP" stood for "flare projector", which was apparently an attempt to disguise the use of its intended purpose by obscuring the nature of the project. It was packed with ten rounds of ammunition and was intended to be used for assassinating enemy soldiers so that their weapons could then be captured and used by the insurgents. The instructions were pictorial, so that the gun could be distributed in any theatre of war, and used even by illiterate operators. The country in which the largest quantity was used was the Philippines.

The CIA Deer gun was a single-shot 9×19 mm Parabellum pistol, made by the U.S. during the Vietnam War. It was packaged with three rounds of ammunition in the grip and packed with instructions in a plastic box. If air-dropped into water, the plastic box containing the pistol would float. Like the earlier FP-45 Liberator, it was designed primarily for assassination of enemy soldiers, with the intention that it would be replaced by an enemy soldier's left-over equipment. The instructions for the Deer Gun were pictorial, with text in Vietnamese.

Although various submachine guns were manufactured in Northern Ireland with "Round Sections" (Round shaped receivers) and "Square Sections" (Square shaped receivers), the Avenger submachine gun which was used by Loyalist Paramilitaries was considered one of the best designs for its type. The bolts were telescoping with a forward recoil/return spring with in the rear, a heavy coil spring that acts as a buffer increasing accuracy and recoil handling. The barrels were usually found lacking rifling but this can in some cases possibly increase ballistics at close quarters. It used Sten magazines and had the capabilities of adapting suppressors.[72]

During the 1970s–80s, International Ordnance Group of San Antonio, Texas released the MP2 machine pistol. It was intended as a more compact alternative to the British Sten gun (although in its components and overall design have nothing directly similar to the STEN), to be used in urban guerrilla actions, to be manufactured cheaply and/or in less-than-well-equipped workshops and distributed to "friendly" undercover forces. Much like the previously mentioned FP-45 "Liberator" pistol of World War 2, it could be discarded during an escape with no substantial loss for the force's arsenal. The MP2 is a blowback-operated weapon that fires from an open bolt with an extremely high rate of fire. A more common weapon of Guatemalan origin is the SM-9. Another example is the Métral submachine gun designed by Gerard Métral intended for manufacture during occupation and undercover circumstances.[73][74]

A unique example is the Soviet S4M pistol, designed to be used expressly for the purpose of assassination. It was a simple break-open, two-shot derringer, but the unique features came from its specialized ammunition, designed around a cut-down version of the 7.62mm rounds used in the Soviet AK-47. The casings of the round contained a piston-like plunger between the bullet and the powder that would move forward inside the casing when fired. The piston would push the round down the barrel and plug the end of the casing, completely sealing off any explosive gases in the casing. This, combined with the inherently low-velocity round resulted in a truly silent pistol. The nature of the gun and ammunition led to it being wildly inaccurate outside of point-blank range. To add further confusion and throw possible suspicion away from the assassin, the barrel rifling was designed to affect the bullet in such a way that ballistics experts would not only conclude that the round was fired from an AK-47, but that the round was fired from several hundred feet away. Due to the politically devastating nature inherent in this design, the S4M was kept highly secret. Information on the pistol was not known by western governments until well after the end of the Cold War.[citation needed]

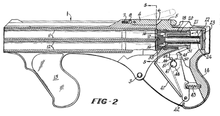

The Winchester Liberator is a 16-gauge, four-barrelled shotgun, similar to a scaled-up four-shot double-action derringer. It was an implementation of the Hillberg Insurgency Weapon design. Robert Hillberg, the designer, envisioned a weapon that was cheap to manufacture, easy to use, and provided a significant chance of being effective in the hands of someone who had never handled a firearm before. Pistols and submachine guns were eliminated from consideration due to the training required to use them effectively. The shotgun was chosen because it provided a high hit probability. Both Winchester and Colt built prototypes, although the Colt eight-shot design came late in the war and was adapted for the civilian law enforcement market. No known samples were ever produced for military use.

More specifically, this invention relates to a four barrel break-open firearm which has a minimum number of working parts, is simple to operate even by inexperienced personnel, and is economical to manufacture.

— Second paragraph of U.S. Patent 3,260,009, by Robert Hillberg granted 1964

Dual-use weapons

Some purpose-designed insurgency weapons were designed for a dual use–that is for use by both insurgents and conventional soldiers. The Welrod pistol was a simple, bolt-action pistol developed by the SOE for use in World War II. It was designed for supplying to foreign British-aligned insurgents and for use by covert British forces. The pistol was designed with an integral sound suppressor, and was ideal for killing sentries and other covert work; the bolt-operated action meant that cocking the gun produced almost no noise, and the bulky but efficient suppressor eliminated nearly all of the muzzle blast. Welrod pistols included a magazine that doubled as a hand-grip, and were originally produced with no markings save a serial number.

The Sten was a 9×19 mm Parabellum submachine gun manufactured by the United Kingdom in World War II. Although not designed as an insurgency weapon, it was designed at a time when Britain had a dire need for weapons and was designed to be easily produced in basic machine shops and use a readily available round, it was therefore the ideal weapon to be produced by resistance groups in occupied territories. Towards the end of the war, the German were in need of weapons and they produced both a version of the Sten, the MP 3008, to arm the Volkssturm and near identical copies of the Sten down to makers marks to arm the Werwolf insurgency force.

Land mines

Land mines have been used extensively by insurgents throughout Cold War and post-Cold War conflicts such as the First Indochina War, Vietnam War, South African Border War and conflicts in Iraq, Syria and Yemen by insurgents as a method of area denial, psychological warfare and attrition.

During the Portuguese Colonial War, mines and other booby traps were one of the principal weapons used by African nationalist insurgents against Portuguese mechanized forces to great effect, who typically patrolled the mostly unpaved roads of their territories using motor vehicles and armored scout cars.[75] To counter the mine threat, Portuguese engineers commenced the herculean task of tarring the rural road network.[76] Mine detection was accomplished not only by electronic mine detectors, but also by employing trained soldiers (picadors) walking abreast with long probes to detect nonmetallic road mines. Guerrillas in all the various revolutionary movements used a variety of mines, often combining anti-tank with anti-personnel mines to ambush Portuguese formations with devastating results. A common tactic was to plant large anti-vehicle mines in a roadway bordered by obvious cover, such as an irrigation ditch, then seed the ditch with anti-personnel mines. Detonation of the vehicle mine would cause Portuguese troops to deploy and seek cover in the ditch, where the anti-personnel mines would cause further casualties. If the insurgents planned to confront the Portuguese openly, one or two heavy machine guns would be sited to sweep the ditch and other likely areas of cover. Mines used included the PMN (Black Widow), TM-46, and POMZ, amphibious mines such as the PDM, and numerous home-made antipersonnel wood box mines and other nonmetallic explosive devices. The impact of mining operations, in addition to causing casualties, undermined the mobility of Portuguese forces, while diverting troops and equipment from security and offensive operations to convoy protection and mine clearance missions.

During the Rhodesian Bush War, the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA) tried to paralyse the Rhodesian effort and economy by planting Soviet anti-tank mines on the roads. From 1972 to 1980 there were 2,504 vehicle detonations of land mines (mainly Soviet TM46s), killing 632 people and injuring 4,410. Mining of roads increased 33.7% from 1978 (894 mines or 2.44 mines were detonated or recovered per day) to 1979 (2,089 mines or 5.72 mines a day).[77] In response, the Rhodesians co-operated with the South Africans to develop a range of mine-protected vehicles. They began by replacing air in tyres with water which absorbed some of the blast and reduced the heat of the explosion. Initially, they protected the bodies with steel deflector plates, sandbags and mine conveyor belting. Later, purpose-built vehicles with V-shaped blast hulls dispersed the blast, and deaths in such vehicles became unusual events. [78] These developments subsequently led to the South African Hippo, Casspir, Mamba and Nyala wheeled light troop carriers.

Land mines were commonly deployed by insurgents during the South African Border War, leading directly to the development of the first dedicated mine-protected armoured vehicles in South Africa. Namibian insurgents used anti-tank mines to throw South African military convoys into disarray before attacking them. In the areas of fighting that covered vast sparsely populated areas of southern Angola and northern Namibia, it was easy for small groups to infiltrate and lay their mines on roads before escaping again often undetected. The anti-tank mines were most often placed on public roads used by civilian and military vehicles and had a great psychological effect. Mines were often laid in complex arrangements. One tactic was to lay multiple mines on top of each other to increase the blast effect. Another common tactic was to link together several mines placed within a few metres of each other, so that all would detonate when any one was triggered. To discourage detection and removal efforts, they also laid anti-personnel mines directly parallel to the anti-tank mines. This initially resulted in heavy South African military and police casualties, as the vast distances of road network vulnerable to insurgent sappers every day made comprehensive detection and clearance efforts impractical. The only other viable option was the adoption of mine-protected vehicles which could remain mobile on the roads with little risk to their passengers even if a mine was detonated. South Africa is widely credited with inventing the v-hull, a vee-shaped hull for armoured vehicles which deflects mine blasts away from the passenger compartment.[79][80]

During the Iraqi,[81] Syrian[82][83] and Yemeni[84] civil wars, landmines have been used for both defensive and guerrilla purposes. Anti-tank mines were also used extensively in Cambodia and along the Thai border, many planted by Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge insurgency. Millions of these mines remain in the area, despite clearing efforts. It is estimated that they cause hundreds of deaths annually to civilians.

Improvised artillery

Improvised and homemade mortars, howitzers and rocket launchers have been used by insurgent groups to attack fortified military installations or to terrorize civilians. They are usually constructed by in a variety of different ways, for example, from heavy steel piping mounted on a steel frame. These weapons may fire factory-made or improvised rounds, and can contain many different explosive fillers and firing mechanisms.

"Barrack buster" is the colloquial name given to several improvised mortars developed in the 1990s by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) during The Troubles. There was several different versions of these mortars constructed by the PIRA, with the most commonly used being the Mark 15 320mm mortar, which fired a projectile constructed of a gas cylinder filled with 196-220 pounds (89-100 kg) of homemade explosives which was remarked as having the effect of a "flying car bomb", and was used in several different attacks on British Army and RUC bases. It was also used in attacks on a number of British helicopters, two of which were successfully shot down in 1994; a British Army Westland Lynx multipurpose helicopter, and an RAF Aérospatiale SA 330 Puma transport helicopter. Several other types of improvised mortars were created by the PIRA during the Troubles, including the "Mark 16” or "Projected Recoilless Improvised Grenade", which was used more like a rocket launcher and fired a projectile made of a tin can filled with 600g of Semtex, the "Mark 12” or "Improvised Propelled Grenade" which fired a 40 ounce (1.1 kg) warhead horizontally at security forces bases and vehicles, and the "Mark 10”, which fired a 44–220 pound (20–100 kg) warhead, one of which was responsible for the first intentional killing of a British soldier in a mortar attack. Because of the weight of these mortars, they often had to be transported on vehicles such as tractors and vans.

Improvised artillery has been used extensively by various factions of the Syrian opposition during the Syrian civil war as a way of making up for deficits in the quantity of military-grade artillery. These "Hell Cannons", as they are known, have been used by various anti-government and Jihadist groups and can fire both improvised and factory-made rounds. The first of these weapons were made in 2012 by the Islamist Ahrar al-Shamal Brigade in the Idlib Governorate around the city of Binnish before the manufacturing was moved to Aleppo by the Free Syrian Army's 16th Division which also appropriated the design. The knowledge spread to other groups in Syria, including the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. Variants of these cannons have also been developed by rebel forces, including the "Thunder Cannon" made from the body of a 100mm tank gun round, the "Mortar Cannon" made by the FSA's 16th Division that fires factory-made rounds, a compressed air cannon made by Ahrar al-Sham, the "Hellfire Cannon" and a number of multi-barrelled cannons such as the 4-barrelled "Quad Hell Cannon" and the 7-barrelled "Bureji" which is named after a Palestinian refugee camp in Gaza.

See also

- Armed Insurrection

- Counter-insurgency

- Free war

- Freedom Fighters (disambiguation)

- "Yank" Levy

- Insurgency weapons and tactics

- List of guerrilla movements

- List of guerrillas

- List of revolutions and rebellions

- Militia

- New generation warfare

- Partisan (military)

- Resistance during World War II

- Special forces

- Civilian Irregular Defense Group program

- United Nations Partisan Infantry Korea

- Violent non-state actor

- National Liberation Front of South Vietnam

- TM 31-210 Improvised Munitions Handbook

Notes

- ^ Asprey 2023.

- ^ a b OED 2023.

- ^ etymonline 2023.

- ^ Keeley 1997, p. 75.

- ^ Leonard 1989, p. 728.

- ^ Snyder 1999, p. 46.

- ^ Laqueur 1977, p. 7.

- ^ Ellis 2005, pp. 99–102.

- ^ "彭越,一个历史量身打造的游击战术的鼻祖". www.sohu.com. Retrieved 29 October 2024.

- ^ "彭越游击战:刘邦反楚的重要推手". Retrieved 29 October 2024.

- ^ McMahon 2016, pp. 22–33.

- ^ Dennis 1985, p. 147.

- ^ Hooper & Bennett 1996, pp. 68-.

- ^ Hanhimäki, Blumenau & Rapaport 2013, pp. 46–73.

- ^ Duff 2014.

- ^ Wilson 1883.

- ^ Pons 1998.

- ^ islamicus 2023.

- ^ Boot 2013, pp. 10–11, 55.

- ^ Ferriter 2020.

- ^ historyireland 2003.

- ^ Chisholm 1911, p. 585.

- ^ Horne 2022.

- ^ Drew 2015, pp. 22–43.

- ^ Chamberlin 2015.

- ^ Boeke 2019.

- ^ Kruijt, Tristán & Álvarez 2019.

- ^ Mao 1989.

- ^ Guevara 2006.

- ^ Lenin 1906.

- ^ Guevara 2006, p. 16.

- ^ Guevara 2006, p. 17.

- ^ Guevara 2006, p. 13.

- ^ Tomes 2004.

- ^ Creveld 2000, pp. 356–358.

- ^ Mao 1965, p. 124.

- ^ McNeilly 2003, pp. 6–7.

- ^ McNeilly 2003, p. 204.

- ^ Detsch 2017.

- ^ Child Soldiers International 2016.

- ^ United Nations Secretary-General 2017.

- ^ Child Soldiers International 2012.

- ^ Emmerson 2016.

- ^ Halibozek, Jones & Kovacich 2008, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Williamson 2009, p. 38.

- ^ Sinclair & Antonius 2012, p. 30.

- ^ Rowe 2002, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Tamer 2017.

- ^ "home.mytelus.com". home.mytelus.com. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ^ a b Ali Ahmad Jalali, Lester W. Grau. The Other Side of the Mountain: Mujahideen Tactics in the Soviet-Afghan War. United States Marine Corps Studies and Analysis Division. pp. 126–127. ISBN 978-1-62358-055-1.

- ^ a b c Grau, Lester W. "IEDs, Land Mines, and Booby Traps in the Soviet-Afghan War" (PDF).

- ^ Grau, Lester W. The Bear Went Over the Mountain: Soviet Combat Tactics in Afghanistan. p. 82.

- ^ a b Billingsley, Dodge. Fangs of the Lone Wolf: Chechen Tactics in the Russian-Chechen Wars 1994-2009. p. 172.

- ^ a b Kulikov, Sergey. "The Tactics of Insurgent Groups in the Republic of Chechnya" (PDF).

- ^ Sethi, Aman (4 April 2010). "Troop fatality figures show changing Maoist strategy". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "Suicide Terrorism: A Global Threat". PBS. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- ^ "13 killed in blasts, arson in Sri Lanka". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 13 April 2006. Archived from the original on 14 April 2006. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- ^ Rafal E. Stolarski, The Production of Arms and Explosive Materials by the Polish Home Army in the Years 1939–1945. Archived 2016-08-23 at the Wayback Machine Archived 30 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine Translated from Polish by Antoni Bohdanowicz. Article on the pages of the London Branch of the Polish Home Army Ex-Servicemen Association. Retrieved 14 March 2008.

- ^ Evan McGilvray (19 July 2015). Days of Adversity: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Helion & Company. pp. 6–. ISBN 978-1-912174-34-8

- ^ Zastava M48 Mauser: Milsurp Gem Breach, Bang, Clear. Bucky Lawson. June 16, 2023

- ^ Syrian Civil War: WWII weapons used WWIIAfterWWII. June 27, 2017

- ^ CCB-18 Memorial Fund Archived 2014-10-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wilson, Jim (March 2004). "Weapons of the Insurgents". Popular Mechanics. Vol. 181, no. 3. Hearst Magazines. ISSN 0032-4558.

- ^ "Army News | News from Afghanistan & Iraq - Army Times". archive.is. 19 July 2012. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "The RPG-7 On the Battlefields of Today and Tomorrow". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ a b Harnden, Toby (1 February 2016). Dead Men Risen: The Welsh Guards and the Defining Story of Britain's War in ... - Toby Harnden - Google Books. Quercus. ISBN 9781849168052. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "News". The Telegraph. 15 March 2016. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "Foreign Military Studies Office Publications - Russian-Manufactured Armored Vehicle Vulnerability in Urban Combat: The Chechnya Experience". 30 April 2010. Archived from the original on 30 April 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ Ernesto "Che" Guevara (1961). Guerrilla Warfare. Praeger.

- ^ US Department of Justice, District of Connecticut. "Project Safe Neighborhoods" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2004.

- ^ UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT. "UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. BARRY WILLIAM DOWNER" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ^ "08 - May - 2009 -". Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ^ The Do-it-Yourself Submachine Gun: Its Homemade, 9mm, Lightweight, Durable And Itll Never Be On Any Import Ban Lists!. Paladin Press (September 1, 1985) English, ISBN 0-87364-840-4, ISBN 978-0-87364-840-0

- ^ "Métral Clandestine SubMachineGun 9x19mm". Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ^ Abbott, Peter and Rodrigues, Manuel, Modern African Wars 2: Angola and Mozambique 1961-74, Osprey Publishing (1998), p. 23: It is estimated that mines planted by insurgents caused about 70 per cent of all Portuguese casualties.

- ^ Abbott, Peter and Rodrigues, Manuel, Modern African Wars 2: Angola and Mozambique 1961–74, Osprey Publishing (1998), p. 23

- ^ Wood, J. R. T. (24 May 1995). "Rhodesian Insurgency". See here www.jrtwood.com for confirmation of authorship.

- ^ Wood, J. R. T. (1995). "The Pookie: a History of the World's first successful Landmine Detector Carrier". Durban. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ^ Camp, Steve; Helmoed-Römer, Heitman (November 2014). Surviving the Ride: A pictorial history of South African Manufactured Mine-Protected vehicles. Pinetown: 30 Degrees South. pp. 19–34. ISBN 978-1-928211-17-4.

- ^ "Namibia". Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- ^ Cousins, Sophie (February 20, 2015). "The treacherous battle to free Iraq of landmines". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on October 11, 2017. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- ^ Mines Advisory Group (January 11, 2017). "New landmine emergency threatens communities in Iraq and Syria". reliefweb.int. Archived from the original on October 11, 2017. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- ^ "Islamic State is losing land but leaving mines behind". The Economist. March 30, 2017. Archived from the original on March 7, 2018. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- ^ "Yemen: Houthi-Saleh Forces Using Landmines". Human Rights Watch. April 20, 2017. Archived from the original on March 22, 2018. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

References

- Asprey, Robert Brown (2023). "guerrilla warfare". Entry within britannica.

- Boeke, Sergei (2019). "Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb". International Relations. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/obo/9780199743292-0267. ISBN 978-0-19-974329-2. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- Boot, Max (2013). Invisible Armies: An Epic History of Guerrilla Warfare from Ancient Times to the Present. Liveright. pp. 10–11, 55. ISBN 978-0-87140-424-4.

- Chamberlin, Paul Thomas (2015). The global offensive : the United States, the Palestine Liberation Organization, and the making of the post-cold war order. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-021782-2. OCLC 907783262.

- Child Soldiers International (2012). "Louder than words: An agenda for action to end state use of child soldiers". Archived from the original on 8 March 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- Child Soldiers International (2016). "A law unto themselves? Confronting the recruitment of children by armed groups". Archived from the original on 8 March 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- Creveld, Martin van (2000). "Technology and War II:Postmodern War?". In Charles Townshend (ed.). The Oxford History of Modern War. New York, USA: Oxford University Press. pp. 356–358. ISBN 978-0-19-285373-8.

- Dennis, George (1985). Three Byzantine Military Treatises. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks. p. 147.

- Detsch, J (2017). "Pentagon braces for Islamic State insurgency after Mosul". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 12 July 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Drew, Allison (2015). "Visions of liberation: the Algerian war of independence and its South African reverberations". Review of African Political Economy. 42 (143): 22–43. doi:10.1080/03056244.2014.1000288. hdl:10.1080/03056244.2014.1000288. ISSN 0305-6244. S2CID 144545186.

- Duff, James Grant (2014). The History Of The Mahrattas. Pickle Partners Publishing. p. 376. ISBN 9781782892335.

- Ellis, Joseph J. (2005). His Excellency : George Washington. New York: Vintage Books. pp. 92–109. ISBN 9781400032532 – via Internet Archive.

- Emmerson, B (2016). "Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism" (PDF). www.un.org. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- etymonline (2023). "guerrilla". Origin and meaning of guerrilla by Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- Ferriter, Diarmaid (2020). "Diarmaid Ferriter: Bloody Sunday 1920 changed British attitudes to Ireland". The Irish Times.

- Guevara, Ernesto Che (2006). Guerrilla Warfare – via Internet Archive.

- Halibozek, Edward P.; Jones, Andy; Kovacich, Gerald L. (2008). The corporate security professional's handbook on terrorism (illustrated ed.). Elsevier (Butterworth-Heinemann). pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-7506-8257-2. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- Hanhimäki, Jussi M.; Blumenau, Bernhard; Rapaport, David (2013). "The Four Waves of Modern Terrorism" (PDF). An International History of Terrorism: Western and Non-Western Experiences. Routledge. pp. 46–73. ISBN 9780415635417. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2014.

- historyireland (2003). "Bloody Sunday 1920: new evidence".

- Hooper, Nicholas; Bennett, Matthew (1996). Cambridge illustrated atlas, warfare : the Middle Ages, 768-1487. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44049-3 – via Internet Archive.

- Horne, Alistair (2022). "A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954–1962. Rev. ed". The SHAFR Guide Online. doi:10.1163/2468-1733_shafr_sim220070002. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- islamicus (2023). "ABD EL-KRIM". Islamicus. Archived from the original on 14 June 2023.

- Keeley, Lawrence H. (1997). War Before Civilization. Oxford University Press.

- Kruijt, Dirk; Tristán, Eduardo Rey; Álvarez, Alberto Martín (2019). Latin American Guerrilla Movements: Origins, Evolution, Outcomes. Routledge. ISBN 9780429534270.

- Laqueur, Walter (1977). Guerrilla : a historical and critical study. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 9780297771845 – via Internet archive.

- Lenin, V. I. (1906). "Guerrilla Warfare". Archived from the original on 11 May 2023 – via Internet archive.

- Leonard, Thomas M. (1989). Encyclopedia of the developing world.

- Mao, Zedong (1965). Selected Works: A Single Spark Can Start a Prairie Fire. Vol. I. Foreign Languages Press – via Internet Archive.

- Mao, Zedong (1989). On Guerrilla Warfare. Washington: U.S. Marine Corps – via Internet Archive.

- McMahon, Lucas (2016). "De Velitatione Bellica and Byzantine Guerrilla Warfare" (PDF). The Annual of Medieval Studies at CEU. 22: 22–33. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2021.

- McNeilly, Mark (2003). Sun Tzu and the Art of Modern Warfare. p. 204.

- OED (2023). "guerrilla". Oxford English Dictionary.

- Pons, Frank Moya (1998). The Dominican Republic: a national history. Markus Wiener Publishers. ISBN 978-1-55876-192-6. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- Rowe, P (2002). "Freedom fighters and rebels: the rules of civil war". J R Soc Med. 95 (1): 3–4. doi:10.1177/014107680209500102. PMC 1279138. PMID 11773342.

- Snyder, Craig (1999). Contemporary security and strategy.

- Sinclair, Samuel Justin; Antonius, Daniel (2012). The Psychology of Terrorism Fears. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-538811-4.

- Tamer, Dr. Cenk (25 September 2017). "The Differences Between the Guerrilla Warfare and Terrorism".

- Tomes, Robert (2004). "Relearning Counterinsurgency Warfare" (PDF). Parameters. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2010.

- United Nations Secretary-General (2017). "Report of the Secretary-General: Children and armed conflict, 2017". www.un.org. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Williamson, Myra (2009). Terrorism, war and international law: the legality of the use of force against Afghanistan in 2001. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-7403-0.

- Wilson, William John (1883). History of Madras Army. Printed by E. Keys at the Govt. Press – via Internet Archive.

Attribution:

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Flying column". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 585.

Further reading

- Asprey, Robert. War in the Shadows: The Guerrilla in History

- Beckett, I. F. W. (15 September 2009). Encyclopedia of Guerrilla Warfare (Hardcover). Santa Barbara, California: Abc-Clio Inc. ISBN 978-0874369298. ISBN 9780874369298

- Derradji Abder-Rahmane, The Algerian Guerrilla Campaign Strategy & Tactics, Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 1997.

- Hinckle, Warren (with Steven Chain and David Goldstein): Guerrilla-Krieg in USA (Guerrilla war in the USA), Stuttgart (Deutsche Verlagsanstalt) 1971. ISBN 3-421-01592-9

- Keats, John (1990). They Fought Alone. Time Life. ISBN 0-8094-8555-9

- Kreiman, Guillermo (2024). "Revolutionary days: Introducing the Latin American Guerrillas Dataset". Journal of Peace Research.

- MacDonald, Peter. Giap: The Victor in Vietnam

- The Heretic: the life and times of Josip Broz-Tito. 1957.

- Oller, John. The Swamp Fox: How Francis Marion Saved the American Revolution. Boston: Da Capo Press, 2016. ISBN 978-0-306-82457-9.

- Peers, William R.; Brelis, Dean. Behind the Burma Road: The Story of America's Most Successful Guerrilla Force. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1963.

- Polack, Peter. Guerrilla Warfare; Kings of Revolution Casemate,ISBN 9781612006758.

- Thomas Powers, "The War without End" (review of Steve Coll, Directorate S: The CIA and America's Secret Wars in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Penguin, 2018, 757 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXV, no. 7 (19 April 2018), pp. 42–43. "Forty-plus years after our failure in Vietnam, the United States is again fighting an endless war in a faraway place against a culture and a people we don't understand for political reasons that make sense in Washington, but nowhere else." (p. 43.)

- Schmidt, LS. 1982. "American Involvement in the Filipino Resistance on Mindanao During the Japanese Occupation, 1942–1945" Archived 5 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine. M.S. Thesis. U.S. Army Command and General Staff College. 274 pp.

- Sutherland, Daniel E. "Sideshow No Longer: A Historiographical Review of the Guerrilla War." Civil War History 46.1 (2000): 5–23; American Civil War, 1861–65

- Sutherland, Daniel E. A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War (U of North Carolina Press, 2009). online Archived 24 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Weber, Olivier, Afghan Eternity, 2002

External links

- abcNEWS: The Secret War on YouTube – Pakistani militants conduct raids in Iran

- abcNEWS Exclusive: The Secret War – Deadly guerrilla raids in Iran

- Insurgency Research Group – Multi-expert blog dedicated to the study of insurgency and the development of counter-insurgency policy.

- Guerrilla warfare on Spartacus Educational

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Guerrilla warfare

- Relearning Counterinsurgency Warfare

- Casebook on Insurgency and Revolutionary Warfare United States Army Special Operations Command

- Counter Insurgency Jungle Warfare School (CIJWS)India

- GunTech.com Archived 2017-09-22 at the Wayback Machine page on Hillberg Insurgency Weapons, with pictures of Winchester Liberator and Colt Defender prototypes based on Hillberg patents.dead link

- Canada's National Firearms Association's page on the FP-45 Liberator and the CIA Deer Gun.

- Marstar Canada firearm's retailer's info page on Yugoslavian M-48BO "sanitized" rifle.

- Christian Science Monitor article On 2003 seizure that found a sanitized Sig Sauer pistol. (May 15, 2003 edition, author Warren Richey)

- Modern Firearms: S-4M silent pistol