The Golden Rondelle Theater is a theater at the Johnson Wax Headquarters complex of S. C. Johnson & Son in Racine, Wisconsin, United States. Designed by Lippincott & Margulies, the theater was originally the Johnson's Wax Pavilion at the 1964 New York World's Fair. Construction of the theater began in October 1962, and the attraction opened on April 22, 1964, along with the rest of the World's Fair. The theater included 500 seats under a gold-colored, disk-shaped dome raised above ground. Originally, the theater screened Francis Thompson's short film To Be Alive!, and the rest of the Johnson's Wax Pavilion contained shoeshine machines, a home-information center, and a playground.

After the fair, the theater was relocated to Racine, and two brick pavilions designed by Taliesin Associated Architects were built. The Golden Rondelle was mostly rebuilt from scratch, except for the steelwork. It reopened in July 1967 and was renovated in 1976. Since being relocated to Racine, the Golden Rondelle has hosted numerous films, including several produced by Thompson. The theater has also been used for seminars, lectures, meetings, and events, and it has functioned as a visitor center.

History

World's Fair

Development

Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in Queens, New York, United States, hosted the 1964 New York World's Fair.[1] New York City parks commissioner Robert Moses was president of the New York World's Fair Corporation, which leased the park from the government of New York City.[2] The household-goods company S. C. Johnson & Son of Racine, Wisconsin, had signaled its intention to build a pavilion at the fair by early 1962, leasing space from the World's Fair Corporation.[3] Herbert Fisk Johnson Jr., the company's president, wanted to build an exhibit at the 1964 World's Fair because he had enjoyed the 1939 New York World's Fair.[4] Other S. C. Johnson executives did not want the pavilion to be built,[4] worrying that it would be unprofitable.[5] In spite of these concerns, Johnson had the pavilion built anyway.[5][6]

A groundbreaking ceremony for S. C. Johnson's pavilion took place on October 16, 1962.[7][8] Lippincott & Margulies, which had helped S. C. Johnson devise a brand identity,[9] was hired to design the structure.[10][11] The pavilion was to occupy a 33,000-square-foot (3,100 m2) site in the fair's industrial section, making it the first company from Wisconsin with an exhibit at the fair.[7][10] The structure itself, consisting of a steel canopy above a disc-shaped auditorium,[7][8] was to be dismantled and relocated after the fair.[10][12] Johnson Wax president Howard M. Packard believed that Frank Lloyd Wright, who had designed the Johnson Wax Headquarters in Racine, would have approved of the design if he were still alive.[13] Francis Thompson and Alexander Hammid were commissioned to produce the short film To Be Alive! for the pavilion;[14] the film demonstrated children in various parts of the world maturing into adulthood.[13][15] The film was originally 40 minutes long, but was reduced to 18 minutes to increase visitor throughput.[14]

The pavilion topped out on October 29, 1963, with a ceremony attended by Wisconsin lieutenant governor Jack B. Olson, Johnson Wax executive Robert P. Gardiner, and Miss Wisconsin 1963 titleholder Barbara Bonville.[16] A Norway pine tree from Boscobel, Wisconsin, was shipped to Flushing Meadows in 1963 to be displayed outside the Johnson Wax pavilion.[17] By the end of that year, the theater had been labeled the Golden Rondelle, a reference to the theater's faceted-diamond shape.[18] Due to inclement weather, there were delays in painting the pavilion's exterior and landscaping the site.[13] A short film about the pavilion was broadcast on the television series Challenge in late March 1964,[19] and S. C. Johnson soft-opened the pavilion for journalists on April 8.[13] One-third of S. C. Johnson's annual advertising budget, $5 million, had been spent on the pavilion.[20]

Operation

The World's Fair formally opened on April 22, 1964,[21][22] and the Golden Rondelle Theater was dedicated that day.[23] S. C. Johnson selected ten multilingual college graduates from different countries to serve as the pavilion's hosts;[24] it also hired ten hosts from the U.S.[25] The pavilion originally screened To Be Alive! 24 times a day,[26][27] for which no admission fees were charged.[28] Within a month, 308,615 people had visited the Johnson Wax Pavilion, making it one of the fair's most popular attractions.[26] Visitors included former U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower,[29] as well as various other politicians, actors, and entertainers. On some days, the theater accommodated 13,000 daily visitors, and more than 5,000 people each used the pavilion's shoeshine machines and information center. Guests sometimes had to wait up to 40 minutes to see the film.[26] As such, S. C. Johnson increased the number of daily screenings of To Be Alive!.[26][27] Moses designated June 23, 1964, as "Johnson's Wax Day", during which special events were hosted at the Johnson's Wax Pavilion.[30]

The Johnson's Wax Pavilion had recorded one million visitors by mid-July 1964;[31] the pavilion was especially popular for its free shoeshine service and its film.[32] By September, two million people had visited the pavilion.[33] Toward the end of the fair's first season, screenings of To Be Alive! were shortened slightly so the theater could accommodate more visitors.[34] The pavilion temporarily closed when the first season ended on October 18, 1964.[35] Around 2.5 million people had seen To Be Alive! during the 1964 season,[27][36] making the Johnson's Wax Pavilion one of the most popular attractions at the fair.[37] The pavilion's shoeshine machines had given more than 1 million shoe shines,[27][38] and its information center had answered over 450,000 questions.[27][39] S. C. Johnson renovated the pavilion between the 1964 and 1965 seasons.[40][41] The pavilion's information center was expanded, additional objects were installed in the pavilion's play area, crowd control was improved,[27] and the shoeshine machines were refurbished.[38] Privet bushes were planted around the auditorium,[42] though the auditorium itself was unchanged.[27][43]

The pavilion reopened at the beginning of the fair's second season on April 21, 1965,[44] following a soft opening the previous week.[43] To Be Alive! had continued to garner critical acclaim during the off-season,[36][43] so S. C. Johnson decided to screen the film 30 times a day for the 1965 season.[27] During the first two months of the season, visitation to the pavilion increased compared with 1964, even as overall fairground attendance decreased.[45] The pavilion reached 3 million total visitors in mid-June 1965[45] and 5 million visitors by mid-October.[46] The second season ended on October 17, 1965,[47] with the pavilion recording wait times of up to three hours on that date.[48] The Johnson's Wax Pavilion had recorded 5 million visitors over two seasons, making it the 12th-most-popular attraction at the fair,[49] and it had shined 1.98 million pairs of shoes.[50] A New York Times reporter wrote that To Be Alive! had made the Johnson's Wax Pavilion a successful low-budget attraction.[51] Lippincott & Margulies itself said, "The entire Johnson exhibit has won so much acclaim that our company is pleasantly embarrassed by its success."[5]

Subsequent use

Relocation and reopening

After the fair, the theater was dismantled so it could be relocated.[52][53] S. C. Johnson considered moving the Golden Rondelle Theater to Racine,[54] but no decision had been made on this by late 1965.[55] The company announced in January 1966 that the theater would be relocated to Racine, being rebuilt next to the Johnson Wax Headquarters.[56][57] Taliesin Associated Architects, a firm formed by apprentices of Frank Lloyd Wright, was to design a pair of pavilions flanking the theater.[57][58] The theater would screen To Be Alive! and would also be used for corporate meetings.[59][60] S. C. Johnson donated the pavilion's playground to the Wisconsin State Welfare Board, which reinstalled it at the Southern Colony and Training School, a special education school in Union Grove, Wisconsin.[61][62]

Excavations for the relocated theater began in late June 1966.[60] S. C. Johnson awarded a general contract for the theater's relocation to local firm Johnson & Henrickson,[60] while another local company, Nielsen Iron Works, was hired as the steel contractor.[63] More than a dozen buildings to the north of the headquarters, including property on both sides of 14th Street between Franklin and Howe streets, was acquired and demolished to create a park-like setting for the theater. The structure itself was rebuilt on the south side of 14th Street, and a parking lot was built south of the theater.[64] When the structure itself was rebuilt, the steel shell was the only part of the original pavilion that was retained.[63] The project cost $350,000 in total.[65] The theater was rededicated on July 27, 1967, with a screening of To Be Alive!.[66][67] The Golden Rondelle was the last building added to the Johnson Wax Administration complex until the completion of Fortaleza Hall in 2010.[68]

Initially, the Golden Rondelle Theater screened To Be Alive! 32 times a week.[69][70] The theater also initially hosted S. C. Johnson meetings.[71][72] This consisted of six shows per weekday (with two additional shows on Thursdays) and three shows per day on the weekend.[69] The theater accommodated 140,000 visitors in the year after its relocation, at which point it was one of Racine's most popular attractions.[70] The Capital Times of Madison, Wisconsin, wrote that visitors hardly had to wait to enter the theater in Racine, unlike at the World's Fair.[73] S. C. Johnson hired Llewelyn Davies Associates in 1969 to create plans for redeveloping the area around the Johnson Wax Headquarters.[74] The plan was released in 1970 and called for a public park around the Golden Rondelle Theater and housing north of the theater, which never occurred.[75]

1970s to present

After interest in To Be Alive! declined, the Golden Rondelle began to host other free events in 1972, when Marge Davis was hired as the theater's event organizer.[71] The events there included as workshops,[76] pantomime performances,[77] and the Ecology Film Festival.[78] By 1976, the relocated theater had hosted 700,000 visitors.[79] The same year, to celebrate the American bicentennial, a larger screen and a surround sound system were installed so the theater could display the film American Years.[80] After the bicentennial, visitors had to make reservations to see American Years.[71][81] In addition, the theater hosed annual events such as Christmas gift-making programs, environmental seminars, and St. Patrick's Day folk concerts.[71] The Golden Rondelle Theater was hosting 100,000 annual visitors by the late 1970s, hosting 4,000 events annually.[71] The theater was frequently filled to two-thirds capacity, though more visitors tended to come during the summer.[53] Nearly two-thirds of the theater's events were open to the general public, although S. C. Johnson (which had priority over events at the theater) was responsible for around 35% of the theater's programming.[71]

The Francis Thompson film To Fly was screened at the Golden Rondelle starting in 1978,[53][82] and Johnson Wax began hosting the Kaleidoscope Educational Series at the Golden Rondelle the next year.[83] The Golden Rondelle began screening Thompson's film Living Planet in 1980,[84] and it continued to screen American Years, To Be Alive!, and To Fly as well.[85][86] It also showed IMAX films on its wide screen.[87] To attract visitors, the theater became part of the Greater Milwaukee Visitors and Convention Bureau in the early 1980s.[71] By that decade, the Golden Rondelle Theater had become a visitor center for the headquarters, with guided tours originating out of the theater.[81][88] The Golden Rondelle also hosted community events such as recitals, lectures, and seminars. Religiously and politically neutral nonprofit organizations held meetings at the Golden Rondelle, and the theater produced some of its own comedy and films.[88] In 1986, the theater started displaying another Thompson film, On the Wing, which replaced To Fly.[88][89]

By the 1990s, the theater screened the films Living Planet, On the Wing, and To Be Alive! upon request.[90] Screenings of To Be Alive! had to be halted because the physical film was decaying, though the film was later restored and digitized.[6] About 10,000 of the Johnson Wax Headquarters' annual visitors watched one of the Golden Rondelle's films; many of these visitors hailed from other states or nations.[83] A film about Frank Lloyd Wright in Wisconsin was displayed to these visitors.[91] In addition, 35,000 local students visited the theater annually as part of the Golden Rondelle's Kaleidoscope Educational Series.[83] The Golden Rondelle continues to function as a visitor center for the Johnson Wax Headquarters in the 21st century.[92][93] Tours of the headquarters begin there, and it also hosts events for S. C. Johnson & Son and was rented to third parties.[93] The film Carnauba, A Son's Memoir was also screened at the theater starting in 2002.[94] In addition, the theater's roof was repaired in 2018 after S. C. Johnson staff discovered a leak.[95]

Description

The Golden Rondelle Theater is just north of the Johnson Wax Headquarters' Research Tower,[96] near the intersection of 14th and Franklin streets in Racine, Wisconsin, United States.[63] It was designed by Lippincott & Margulies as a 1964 New York World's Fair pavilion.[10][11] Measuring 90 feet (27 m) in diameter,[7][18][25] the theater has a saucer-shaped, gold-colored roof.[63] The frame uses 300 short tons (270 long tons; 270 t) of steel.[97] According to Lippincott & Margulies, the design was meant to convey the company's brand image so that it could "be readily appreciated by Hottentots or Eskimos".[9] The New York Times cites the design as having been inspired by a church that Frank Lloyd Wright designed.[92]

By the late 20th century, the Golden Rondelle was one of a relatively small number of attractions that remained from the 1964 World's Fair, along with structures such as the Wisconsin Pavilion and pieces of the Coca-Cola and Spanish pavilions.[98] The theater was one of three 1964 World's Fair exhibits in Wisconsin that were detailed in the 2014 documentary After the Fair.[99]

Original layout

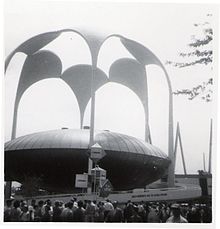

When the theater was located at Flushing Meadows–Corona Park, it sat at the intersection of the Avenue of Europe and the Eisenhower Promenade.[30] The theater was was covered by another canopy with six columns that surrounded a reflecting pool, curving inward at their tops.[10][25] The columns were variously cited as measuring 80 feet (24 m)[10][8] or 90 feet (27 m) high.[16][25][30] Each of the columns was made of concrete and weighed 10 short tons (8.9 long tons; 9.1 t).[100] The canopy above the columns was variously described as resembling a tulip,[101] a clamshell,[102][103][104] or a mixture of a clamshell and a spaceship.[5]

The theater itself was originally 24 feet (7.3 m)[10] or 25 feet (7.6 m) above ground and was accessed by an overpass from a neighboring building.[13][30] There was a double-level promenade surrounding the theater.[10] Inside were 500 seats[5][18][15] or 600 seats,[7][8] which consisted of simple benches.[53][63] There were also three screens each measuring 18 feet (5.5 m) wide,[13][15] which were placed next to each other.[105] In an early precursor to the IMAX film format,[104][106][107] three projectors could display a wide shot across multiple screens or separate images on each screen.[15][105] Another ramp led from the exit to ground level. In addition, a walkway led from the ground to a staging area on the second floor; this walkway was lined with industrial exhibits.[13] The theater's ceiling was filled with batts, which were made of mineral wool.[108][109] The batts reduced vibrations caused by planes at the nearby John F. Kennedy and LaGuardia airports, and it also allowed the auditorium to use smaller air conditioning equipment.[108]

Next to the theater was a two-story building with various educational displays and entertainment,[10][30] These included ten automatic shoe shining machines that could shine visitors' shoes for free.[13][36][110] For the 1964 season, the Home Care Information Center had eight teleprinters,[13] where visitors could ask questions about household matters such as homes, automobiles, and furniture finishes.[111][15] Additional teleprinters were installed during the 1965 season.[36] The queries were sent to computers in the National Cash Register pavilion, and the answers were typed out on the teleprinters.[13][25] There was also a playground on the ground floor, which included robots, mirrors, tunnels, and noisemakers.[13][25] These objects could be moved or unhidden using switches, buttons, and cranks.[62] Marigold flowers were grown in greenhouses and planted around the theater,[112] and there were also privet bushes during the 1965 season.[42]

Reconfiguration

The Golden Rondelle Theater was moved to the Johnson Wax Headquarters after the fair closed.[93][113] It functions as a visitor center for the Johnson Wax Headquarters.[71][93] The roof of the Golden Rondelle is supported by six reinforced-concrete piers. The lower section of the roof is covered with cement plaster, while the upper half is covered with several coats of neoprene, gold-colored synthetic rubber, and a lacquered finish. Both sections of the roof are covered with 500 pounds (230 kg) of plaster glitter, in addition to triangular pieces of precast concrete.[63]

Inside the auditorium are 308[63] or 320 seats.[58] In contrast to the seats in the original pavilion, the current theater has 11 rows of individual, padded seats,[53] arranged in a continental seating layout.[63] The three projectors from the original pavilion were preserved in the relocated theater.[69][73] The three 18-foot-wide screens from the World's Fair were also originally installed at the theater,[73] but they were replaced in 1976 with a single screen.[80] The newer screen measures 54 feet (16 m)[114] or 55 feet (17 m) across[81] and is capable of screening IMAX films.[87] Eleven surround sound speakers also date from the theater's 1976 renovation.[80]

Flanking the theater are two brick pavilion with glass-tube windows, designed by Taliesin Associated Architects.[57] The pavilion to the south includes a lobby and display area, in addition to Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning machinery.[60] Also within the southern pavilion is a hydraulic elevator for disabled patrons.[63] The other structure, to the north, is an exit.[58][60] The pavilions' architecture was intended to complement the Johnson Wax Headquarters' design.[52] The theater's roof is wedged between the pavilions, and part of the roof overhangs the offices inside one of the pavilions.[53]

Reception

When the Johnson's Wax Pavilion was built, a critic for The Cincinnati Enquirer praised the structure for the "buoyant qualities of its circular spaceship-moorings design",[115] while Variety magazine wrote that the building was "themed to inspiration".[15] The New Pittsburgh Courier characterized the pavilion as having "spinnaker-like petals and [a] golden disc-shaped theater",[116] while Time magazine called the canopy "a huge gold clam over a blue pool inside six slender white pylons that rise high and flare into unearthly petals".[102] Ada Louise Huxtable of The New York Times characterized the canopy as one of several "accidental juxtapositions and cockneyed contrasts built into the fair that give it its particular attraction and charm",[101] while Architectural Forum regarded the pavilion as one of a small number of "exceptional" attractions at the fair.[5] By contrast, a reporter for The Atlanta Constitution criticized the fact that the pavilion's movie did not actually promote S. C. Johnson products,[117] and a writer for The Morning News said that the exhibit "may prove rather heady stuff for some" despite its high acclaim.[118]

After the Golden Rondelle Theater was relocated to Racine, the Chicago Tribune wrote that the "golden disc [...] looks much the same as it did when it stood in Flushing Meadow".[66] The Kenosha News wrote that the theater "stands for positive values in an often negative world" mainly because of To Be Alive!,[67] while another Kenosha News article likened the theater to "a spaceship tethered to the ground".[114] Te Racine Journal Times described the theater as a "golden gift" to Racine in 1986,[88] and the same newspaper wrote in 2014 that it "has come to stand as one of the City of Racine's most recognizable symbols".[93] A writer for Backstage magazine wrote that the Golden Rondelle's location was particularly apt because To Be Alive! and the Johnson Wax Headquarters both "challenged traditions".[106] Conversely, The Wall Street Journal wrote that the theater "gleams incongruously, like some vestige of The Jetsons".[104]

References

Citations

- ^ La Guardia International Airport and John F. Kennedy International Airport, Port Authority of New York and New Jersey Airport Access Program, Automated Guideway Transit System (NY, NJ): Environmental Impact Statement. Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, United States Department of Transportation, Federal Aviation Administration, New York State Department of Transportation. June 1994. p. 1.11. Archived from the original on January 23, 2023. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- ^ Schumach, Murray (June 4, 1967). "Moses Gives City Fair Site as Park; Flushing Meadows in Queens Becomes the 2D Biggest Recreation Area Here". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 7, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ Schmedel, Scott R. (May 9, 1962). "GM Plans Costliest Pavilion for New York World's Fair of '64–65: Company Undecided on Contents; Fair Officials Hope the Plan Will Spur Leasing of Space". The Wall Street Journal. p. 9. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 132775520.

- ^ a b Sharma-Jensen, Geeta (September 21, 1986). "Sam Johnson does his homework". The Journal Times. pp. 2G, 3G. Retrieved February 22, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Dunne, Carey (April 24, 2014). "The Golden Rondelle, Space-Age Hit Of 1964". Fast Company. Retrieved February 23, 2025.

- ^ a b Burke, Michael (May 21, 2005). "Sam's lasting wish: 'To Be Alive!' restored". The Journal Times. pp. 1A, 7A. Retrieved February 23, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e "Wisconsin Firm Plans Theater at World's Fair". The Oshkosh Northwestern. UPI. October 16, 1962. p. 4. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ a b c d "Pavilion at World's Fair". Chicago Daily Tribune. October 17, 1962. p. C6. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 182843972.

- ^ a b Kaufman, Michael T. (May 7, 1998). "J. Gordon Lippincott, 89, Dies; Pioneer Design Consultant". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 23, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Johnson's Wax Plans World's Fair Theater". The Journal Times. October 16, 1962. pp. 1A, 2A. Retrieved February 20, 2025; "Novel Theater at the Fair". New York Herald Tribune. October 17, 1962. p. 32. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1342443220.

- ^ a b Perry, Ellen; Burns, James T. Jr. (October 1964). "The Busy Architect's Guide to the World's Fair" (PDF). Progressive Architecture. Vol. 45, no. 10. p. 228. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 19, 2024.

- ^ "Up, Down, Up". The Record. UPI. August 24, 1963. p. 11. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Hoffman, Verne A. (April 9, 1964). "Johnson's 'Golden Disc Theater' Promises Fair-goers Unique Thrill". The Journal Times. p. 4. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ a b "Vaudeville: Johnson Wax's Producers Dittoing to Promote Fair". Variety. Vol. 236, no. 1. August 26, 1964. p. 47. ProQuest 964077904.

- ^ a b c d e f "N.Y. World's Fair: Johnson's Wax Ind Potent Soft". Variety. Vol. 234, no. 8. April 15, 1964. pp. 54, 56. ProQuest 1032432418.

- ^ a b "Spruce Up at the Fair". The Journal Times. October 30, 1963. p. 4. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ "Tree That Grew in Boscobel to Show at New York Fair". The Boscobel Dial. November 14, 1963. p. 9. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ a b c "'Golden Rondelle'". News and Record. United Press International. December 8, 1963. p. 73. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ "Johnson Pavilion at Fair on TV". The Racine Journal-Times Sunday Bulletin. March 29, 1964. p. 6. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ Sharma-Jensen, Geeta (September 21, 1986). "Sam Johnson does his homework". The Journal Times. pp. 2G, 3G. Retrieved February 22, 2025.

- ^ Samuel 2007, p. 32.

- ^ "World's Fair Opens To Picketing; Stall-In Fails: Johnson Foresees Global Peace Soon Rain, Racial Troubles Keep Crowd To 90,000; More Than 290 Integrationists Seized". The Sun. April 23, 1964. p. 1. ProQuest 540050678; Johnson, Thomas A; Aronson, Harvey (April 23, 1964). "Vow More Protests at Fair: Threaten More Protests; 200 Jailed". Newsday. p. 1. ISSN 2574-5298. ProQuest 913631689; "Rain Soaks Crowd; Sit-Ins Mar Festivities at Some Pavilions—Attendance Cut". The New York Times. April 23, 1964. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 14, 2024. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ "Golden Touch at Fair". The Journal Times. April 23, 1964. p. 55. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ "Johnson Pavilion Will Use 10 from Abroad as Hosts". The Journal Times. April 12, 1964. p. 26. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f "Can Get Shoe Shine at Fair". Henryetta Daily Free-Lance. UPI. June 16, 1964. p. 6. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ a b c d "Johnson's 'Off Broadway' Theater a Success". The Journal Times. June 7, 1964. p. 28. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Johnson Won't Change Winning Exhibit at Fair". The Racine Journal-Times Sunday Bulletin. April 11, 1965. p. 42. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ Bach, Erwin (October 8, 1964). "Going to World's Fair? Take Camera, Fast Film: Tells Variety of Subjects for Visitor". Chicago Tribune. p. D12. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 179634143; Harris, Radie (May 8, 1964). "On the Town". Newsday. p. 103. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ Johnson, Thomas A. (June 3, 1964). "You Don't Know Politics? But Ike, Only Last Week..." Newsday. p. 4. Retrieved February 20, 2025; Spagnoli, Eugene (June 3, 1964). "An Added Attraction at the Fair: Ike, Making Like Drama Critic". Daily News. p. 405. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e "Wax Pavilion Wins Fair 'Day' in June". Coney Island Times. August 16, 1963. p. 3. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ "On the House". The Journal Times. July 13, 1964. p. 19. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ "World's Fair Lives Up to Its Billing". Leader-Telegram. UPI. November 1, 1964. p. 2. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ "Sensitive Fingers Bring Fair Into World of 11 Blind Kids". Daily News. September 19, 1964. p. 272. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ Frederick, Robert B. (January 6, 1965). "Pictures: N. Y. World's Fair Showcased Wondrous Sizes and Techniques In Specially-Created Films". Variety. Vol. 237, no. 7. pp. 5, 67. ProQuest 1505834837.

- ^ "Young Employes Say Farewells Gather to Reminisce on Six Months at Fair — Few Expecting to Return". The New York Times. October 19, 1964. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 16, 2024. Retrieved May 16, 2024; Cassidy, Joseph (October 19, 1964). "Fair's Last Day Draws Crowd". New York Daily News. p. 67. ISSN 2692-1251. Archived from the original on May 16, 2024. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "'To Be Alive' Will Again Be Feature at Fair". The Morning Union. April 11, 1965. p. 74. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "N.Y. World's Fair Promoters Cry Foul on Publicity". Chicago Tribune. April 11, 1965. p. 153. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ a b "Changed World's Fair Opens for Second Year April 21". The Troy Record. March 13, 1965. p. 41. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "Homemakers Make Computers Hum". Portland Press Herald. May 16, 1965. p. 72. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ Frederick, Robert B. (October 21, 1964). "N.Y. World's Fair: Hibernating N. Y. Fair Eyes Finale Anni; Seeks New Face for Fun Area". Variety. Vol. 236, no. 9. p. 62. ProQuest 962978940.

- ^ Ferretti, Fred (December 27, 1964). "1965 World's Fair to Ballyhoo International Aspects". The Forum. p. 12. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ a b Aronson, Harvey (April 2, 1965). "World of Difference as Fair Faces 2nd Year". Newsday. p. 15. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ a b c Kuhn, John H. (April 15, 1965). "World's Fair of '65 Readied for Inaugural". The Record. p. 4. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ Alden, Robert (April 22, 1965). "158,000 Open the Fair's Second Year; Paid Admissions Are 3 Times More Than First Day's in '64 158,000, Half of Them Children, Attend World's Fair on Crisp, Sunny Opening Day". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 16, 2024. Retrieved May 16, 2024; O'Neill, Maureen (April 22, 1965). "The Natives Return—They're Hardy Lot". Newsday. p. 91. ISSN 2574-5298. Archived from the original on May 16, 2024. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ a b "Johnson Show Tops 3 Million". The Journal Times. June 13, 1965. p. 13. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "Five Million". The Journal Times. October 15, 1965. p. 4. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ Abrams, Arnold; Smith, Edward G. (October 18, 1965). "Drunks and Vandals Close the Fair: They Dig the World's Fair on Its Last Day". Newsday. p. 1. ISSN 2574-5298. ProQuest 914444914; Alden, Robert (October 18, 1965). "Vandalism Mars Last Day Of the Two-Year Exposition; Weeping Children, Sad Employes and Vandalism Abound as World's Fair Closes". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 16, 2024. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ Mallon, Jack (October 17, 1965). "Hour by Hour, Records Fall at the Fading Fair". Daily News. p. 83. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "Report GM Top Fair Attraction With 29,002,186". The Daily Freeman. October 19, 1965. p. 2. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "Shoe Shine Line Long". The Times Record. AP. December 9, 1965. p. 24. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ Alden, Robert (October 17, 1965). "Despite Controversies, Attendance Passes All Other Expositions; World's Fair, Closing Today, to Establish Record With More Than 51 Million Visitors in 2 Years". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ a b "Movie Featured at World's Fair Goes to Racine". The Morning Call. UPI. February 16, 1966. p. 29. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Woessner, Bob (May 14, 1978). "Racine Theater Shows Award-Winning Movies Free". Green Bay Press-Gazette. p. 12. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "World Fair Demolition Is Wrecker's Bonanza". The Plain Dealer. November 21, 1965. p. 179. Retrieved February 21, 2025; Quigg, H. D. (September 26, 1965). "World's Fair Closeout: Anyone for 'Bargains'?". Democrat and Chronicle. p. 103. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "Changes Policy on Hiring Women". The Journal Times. December 26, 1965. p. 52. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "Johnson Wax Moving Exhibit". Stevens Point Journal. AP. January 13, 1966. p. 6. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ a b c "Redesign Golden Rondelle Theater to Match Johnson Wax Buildings". The Journal Times. January 13, 1966. p. 4. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c Evjue, William T. (December 31, 1966). "Hello, Wisconsin". The Capital Times. pp. 1, 3. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ "Pictures: Johnson Wax Expo Film Shows in Plant Town". Variety. Vol. 241, no. 9. January 19, 1966. p. 32. ProQuest 1017141379.

- ^ a b c d e "Will Break Ground for Golden Rondelle". The Journal Times. June 26, 1966. p. 19. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "World's Fair Device Will Aid Retarded". The Sacramento Bee. AP. July 5, 1966. p. 32. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ a b "Johnson's 'Fair Fun House' is Gift to Southern Colony". The Journal Times. March 10, 1966. p. 29. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "S.C. Johnson's Golden Rondelle Dedication Ceremonies Thursday". The Journal Times. July 26, 1967. p. 5. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ "Johnson Clears Areas to Get Park Setting for Rondelle". The Journal Times. April 2, 1967. p. 49. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ Pfankuchen, Dave (June 11, 1967). "Big Building Projects Are Numerous but Volume Dips from Record Years". The Journal Times. p. 45. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ a b Cross, Robert (July 28, 1967). "And in Racine, a New Theater". Chicago Tribune. p. 43. ISSN 1085-6706. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Edwards, Elaine (July 28, 1967). "'To Be Alive' dedicates theater". Kenosha News. p. 11. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "SC Johnson offers free tours at new corporate building". Kenosha News. February 6, 2010. p. 14. Retrieved February 23, 2025.

- ^ a b c "'To Be Alive' Showings to Begin in Rondelle". The Journal Times. July 23, 1967. p. 6. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ a b "Prize film to be shown to public". Kenosha News. July 2, 1968. p. 6. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tancill, Karen B. (September 7, 1980). "Rondelle shows off its community pride". The Journal Times. p. 47. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ "New Racine Theater Like Flying Saucer". The La Crosse Tribune. July 11, 1967. p. 1. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c Koelsch, J. W. (July 27, 1968). "Golden Rondelle Theater, Racine, Has 'Finest Free Show in State'". The Capital Times. p. 25. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ Sheldon, Robert E. (March 17, 1970). "Southside Study Group Eyes Parks, Shops, Housing, Industry". The Journal Times. p. 1. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ Sheldon, Robert (March 22, 1970). "Business, Industry Role in Revitalization Plan". The Journal Times. p. 15. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ See, for example: "Golden Rondelle Fishing Program". The Journal Times. March 7, 1974. p. 14. Retrieved February 21, 2025; "Workshop encourages health work". Kenosha News. April 14, 1970. p. 6. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "Pantomime group scheduled for Golden Rondelle program". Kenosha News. January 14, 1975. p. 22. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ "Film Festival at Starbuck, Too". The Journal Times. April 8, 1971. p. 9. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ Davies, Donald K. (July 9, 1976). "'American Years' is treat this Bicentennial summer". Wisconsin State Journal. p. 43. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ a b c "Bicentennial Film Produced for Public". Herald-Times-Reporter. July 6, 1976. p. 19. Retrieved February 21, 2025; Tancill, Karen B. (July 2, 1976). "Bicentennial film to open at Rondelle". The Journal Times. p. 7. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

- ^ a b c Murphy, Ken (June 11, 1984). "Golden Rondelle is easy on wallet". Kenosha News. p. 5. Retrieved December 30, 2024.

- ^ Dose, Emmert H. (April 6, 1978). "'To Fly' taking off at Rondelle". The Journal Times. p. 45. Retrieved February 22, 2025.

- ^ a b c Scolaro, Joseph A. (April 27, 1997). "Room with a view". The Journal Times. p. 67. Retrieved February 23, 2025.

- ^ "Living Planet movie showing announced". Ozaukee County News Graphic. July 9, 1980. p. 13. Retrieved February 22, 2025; Thayer, Emily (June 9, 1980). "'Planet Earth' opens at Rondelle". Kenosha News. p. 7. Retrieved February 22, 2025.

- ^ Tancill, Karen B. (September 7, 1980). "Rondelle shows off its community pride". The Journal Times. p. 47. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ "Racine County Tours". The Herald. September 25, 1980. p. 38. Retrieved February 22, 2025.

- ^ a b Higgins, Jim; Higgins, Shirley (August 16, 1981). "IMAX productions eye-opening, exciting: Movie fan's guide". Chicago Tribune. p. J7. ISSN 1085-6706. ProQuest 170506982.

- ^ a b c d Tancill, Karen B. (September 21, 1986). "It's a golden gift to Racine". The Journal Times. p. 75. Retrieved February 22, 2025.

- ^ Jensen, Don (September 30, 1986). "Pterodactyl flies at Rondelle". Kenosha News. p. 7. Retrieved February 22, 2025.

- ^ Campbell, Genie (May 5, 1996). "Racine Shifts Gears From Industrial to Recreational". Wisconsin State Journal. p. 2. ProQuest 390711349.

- ^ Casetta, Curt (March 19, 1999). "Racine buildings have the 'Wright' stuff". The Daily Tribune. p. 11. Retrieved February 23, 2025.

- ^ a b Sharoff, Robert (April 29, 2014). "A Corporate Paean to Frank Lloyd Wright". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 23, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Roberts, Lee B. (September 12, 2014). "Golden Rondelle Theater Is an Architectural Gem". Journal Times. Archived from the original on May 23, 2024. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ Michaelson, Mike (January 20, 2002). "Racine polishes up for visitors; A wax dynasty, Wright designs, fun shops and hearty foods are among top attractions". Des Moines Register. p. F.5. ProQuest 889774720.

- ^ "Sprucing Up the Golden Rondelle". The Journal Times. September 12, 2018. pp. A7. Retrieved February 23, 2025.

- ^ Huhti, T. (2017). Moon Wisconsin. Travel Guide. Avalon Publishing. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-63121-430-1. Retrieved December 25, 2024.

- ^ "Racine County Tours". The Herald. September 25, 1980. p. 38. Retrieved February 22, 2025.

- ^ "Where the Fairs' Artifacts Live On". The New York Times. April 28, 1989. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 22, 2025.

- ^ "Three Wisconsin landmarks featured in documentary". Marshfield News Herald. October 29, 2014. p. 3. ProQuest 1617925648.

- ^ "Won't Wilt". The Sacramento Bee. UPI. February 17, 1964. p. 5. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ a b Huxtable, Ada Louise (April 22, 1964). "Architecture: Chaos of Good, Bad and Joyful: Grotesque Contrasts, Wholly Unplanned, Give Fair Charm Few Ideas Are New – State Pavilion Is Star of Show". The New York Times. p. 25. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 115763522.

- ^ a b "Fairs: The World of Already". TIME. June 5, 1964. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ "Fair Marching on Toward Opening; Overcomes Strikes, Disputes and a Boycott in Drive to Be Ready on April 22". The New York Times. January 22, 1964. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ a b c Buss, Dale (January 10, 2009). "Wright's House of Wax: An office building takes us back to the future of the '30s". The Wall Street Journal. p. W12. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 2651422969.

- ^ a b "Moving Forward; Advance in Art of Cinema Seen in Film at World's Fair". The New York Times. May 10, 1964. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ a b Finehout, Robert M. (April 20, 1984). "The Music Goes Round & Round". Back Stage. Vol. 25, no. 16. pp. 36B, 37B. ProQuest 962980328.

- ^ "The New Commercial Large-format Theatres". Film Journal International. Vol. 102, no. 11. November 1, 1999. p. 20. ProQuest 1286220612.

- ^ a b "Insulation Bars Heat, Noise From Theater at World's Fair". Republican and Herald. February 18, 1964. p. 2. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ Moor, Ruth M. (February 21, 1964). "Why Choose?--Spacious Privacy in Illinois: Transition Difficult". The Christian Science Monitor. p. 13. ISSN 0882-7729. ProQuest 510470662.

- ^ "Something Free". Valley Morning Star. UPI. March 30, 1964. p. 8. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ "More than 70 World Fair Exhibits to Appeal to Feminine Interests". Green Bay Press-Gazette. March 29, 1964. p. 14. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ Garlich, Ed (March 29, 1964). "Across the Fields and Furrows". Jacksonville Journal Courier. p. 16. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ Samuel 2007, p. 85.

- ^ a b Fisher, Dan (July 9, 1988). "Big screen viewing at Golden Rondelle". Kenosha News. p. 34. Retrieved February 22, 2025.

- ^ Radcliffe, E. B. (October 20, 1963). "New York World's Fair Preview Takes Viewer Up to Cloud Nine". The Cincinnati Enquirer. p. 91. Retrieved February 20, 2025.

- ^ "The NY World's Fair Wiil Be Family Affair". New Pittsburgh Courier. April 25, 1964. p. 13. ProQuest 371618347.

- ^ Galphin, Bruce (June 26, 1964). "The World's Fair: Gross, Irresistible". The Atlanta Constitution. p. 4. ProQuest 1554772333.

- ^ Malone, Tom (April 19, 1965). "This Bears Mention". The Morning News. p. 13. Retrieved February 21, 2025.

Sources

- Samuel, Lawrence R. (August 30, 2007). The End of the Innocence: The 1964–1965 New York World's Fair (1st ed.). Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0890-5.