Université libre de Bruxelles

Seal of the ULB | |

| Latin: Universitas Bruxellensis[a] | |

| Motto | Scientia vincere tenebras (Latin) |

|---|---|

Motto in English | Conquering darkness through science |

| Type | Independent (partly state-funded) |

| Established | 28 May 1970 |

| President | Pierre Gurdjian |

| Rector | Annemie Schaus |

Administrative staff | 4,400 |

| Students | 37,489 (2023–24)[1] |

| Location | , Belgium |

| Campus | Solbosch/Solbos, La Plaine/Het Plein, Erasme/Erasmus, Gosselies |

| Follows | Free University of Brussels |

| Affiliations | |

| Website | www.ulb.be |

| |

| |

The Université libre de Bruxelles (French, pronounced [ynivɛʁsite libʁ də bʁysɛl]; lit. Free University of Brussels; abbreviated ULB) is a French- and English-speaking research university in Brussels, Belgium. It has three campuses: the Solbosch/Solbos campus (in the City of Brussels and Ixelles), the La Plaine/Het Plein campus (in Ixelles) and the Erasme/Erasmus campus (in Anderlecht).

The Université libre de Bruxelles was formed in 1969 by the splitting of the Free University of Brussels,[b] which was founded in 1834 by the lawyer and liberal politician Pierre-Théodore Verhaegen. The founder aimed to establish a university independent from state and church, where academic freedom would prevail.[2] This is still reflected in the university's motto Scientia vincere tenebras, or "Conquering darkness through science".

In 2012, the ULB had about 24,200 students, a diverse student population as well as a diverse staff.[3]

Name

Brussels has two universities whose names mean Free University of Brussels in English: the French-speaking Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB) and the Dutch-speaking Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB). Neither uses the English translation, since it is ambiguous.

History

Establishment of a university in Brussels

The history of the Université libre de Bruxelles is closely linked with that of Belgium itself. When the Belgian State was formed in 1830 by nine breakaway provinces from the Kingdom of the Netherlands, three state universities existed in the cities of Ghent, Leuven and Liège, but none in the new capital, Brussels. Since the government was reluctant to fund another state university, a group of leading intellectuals in the fields of arts, science, and education — amongst whom the study prefect of the Royal Athenaeum of Brussels, Auguste Baron, as well as the astronomer and mathematician Adolphe Quetelet — planned to create a private university, which was permitted under the Belgian Constitution.[4][2]

In 1834, the Belgian episcopate decided to establish a Catholic university in Mechelen with the aim of regaining the influence of the Catholic Church on the academic scene in Belgium, and the government had the intent to close the university at Leuven and donate the buildings to the Catholic institution.[5] The country's liberals strongly opposed to this decision, and furthered their ideas for a university in Brussels as a counterbalance to the Catholic institution. At the same time, Auguste Baron had just become a member of the freemasonic lodge Les Amis Philantropes. Baron was able to convince Pierre-Théodore Verhaegen, the president of the lodge, to support the idea for a new university. On 24 June 1834, Verhaegen presented his plan to establish a free university.[2]

After sufficient funding was collected among advocates, the Université libre de Belgique ("Free University of Belgium") was inaugurated on 20 November 1834, in the Gothic Room of Brussels Town Hall. The date of its establishment is still commemorated annually, by students of its successor institutions, as a holiday called Saint Verhaegen (often shortened to St V) for Pierre-Théodore Verhaegen.[6] In 1836, the university was renamed the Université libre de Bruxelles ("Free University of Brussels").[4]

After its establishment, the Free University faced difficult times, since it received no subsidies or grants from the government; yearly fundraising events and tuition fees provided the only financial means. Verhaegen, who became a professor and later head of the new university, gave it a mission statement which he summarised in a speech to King Leopold I: "the principle of free inquiry and academic freedom uninfluenced by any political or religious authority."[2] In 1858, the Catholic Church established the Saint-Louis Institute in the city, which subsequently expanded into a university in its own right.[7]

Growth and internal tensions

The Free University grew significantly over the following decades. In 1842, it moved to the Granvelle Palace, which it occupied until 1928. It expanded the number of subjects taught and, in 1880, became one of the first institutions in Belgium to allow female students to study in some faculties. In 1893, it received large grants from Ernest and Alfred Solvay as well as Raoul Warocqué to open new faculties in Brussels. A disagreement over an invitation to the anarchist geographer Élisée Reclus to speak at the university in 1893 from the rector Hector Denis led to some of the liberal and socialist faculty splitting away from the Free University to form the New University of Brussels (Université nouvelle de Bruxelles) in 1894. However, the institution failed to displace the Free University and closed definitively in 1919.[8]

In 1900, the Free University's football team won the bronze medal at the Summer Olympics. After Racing Club de Bruxelles declined to participate, a student selection with players from the university was sent by the Federation.[9][10] The team was enforced with a few non-students.[11] The Institute of Sociology was founded in 1902, then in 1904 the Solvay School of Commerce, which would later become the Solvay Brussels School of Economics and Management (part of ULB) and VUB Solvay Business School (part of VUB). In 1911, the university obtained its legal personality under the name Université libre de Bruxelles - Vrije Hogeschool te Brussel.[12]

German occupation and move

The German occupation during World War I led to the suspension of classes for four years in 1914–1918. In the aftermath of the war, the Free University moved its principal activities to the Solbosch/Solbos in the southern municipality of Ixelles, and a purpose-built university campus was created, funded by the Belgian American Educational Foundation.

During the second occupation of World War II, the university protested the two anti-Jewish ordinances of 28 October 1940, but nevertheless collaborated for the expulsion of Jewish professors and students.[13] However, the university ceased its collaboration when it came to accepting Flemish professors of the New Order.[14] Thus, the university was again closed by the German authorities on 25 November 1941, and some of its students were involved in the Belgian Resistance, establishing the sabotage-orientated network Groupe G.[15]

Splitting of the university

Courses at the Free University were taught exclusively in French until the early 20th century. After Belgian independence, French was widely accepted as the language of the bourgeoisie and upper classes and was the only medium in law and academia. As the Flemish Movement gained prominence among the Dutch-speaking majority in Flanders over the late 19th century, the lack of provision for Dutch speakers in higher education became a major source of political contention. Ghent University became the first institution in 1930 to teach exclusively in Dutch.

Some courses at the Free University's Faculty of Law began being taught in both French and Dutch as early as 1935. Nevertheless, it was not until 1963 that all faculties offered their courses in both languages.[16] Tensions between French- and Dutch-speaking students in the country came to a head in 1968 when the Catholic University of Leuven split along linguistic lines, becoming the first of several national institutions to do so.[17]

On 1 October 1969, the French and Dutch entities of the Free University separated into two distinct sister universities. This splitting became official with the act of 28 May 1970, of the Belgian Parliament, by which the French-speaking Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB) and the Dutch-speaking Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB) officially became two separate legal, administrative and scientific entities.[18][19]

Campuses

The ULB comprises three main campuses: the Solbosch/Solbos campus, on the territories of the City of Brussels and Ixelles municipalities in the Brussels-Capital Region, the La Plaine/Het Plein campus in Ixelles, and the Erasme/Erasmus campus in Anderlecht, beside the Erasmus Hospital.

The main and largest campus of the university is the Solbosch, which hosts the administration and general services of the university. It also includes most of the faculties of the humanities, the École polytechnique, the large library of social sciences, and among the museums of the ULB, the Museum of Zoology and Anthropology,[20] the Allende exhibition room and the Michel de Ghelderode Museum-Library.

The La Plaine campus hosts the Faculty of Science and the Faculty of Pharmacy. There are also the Experimentariums of physics and chemistry, the Museum of Medicinal Plants and Pharmacy[21] and student housing. This site is served by Delta station.

The Erasmus campus houses the Erasmus Hospital and the Pôle Santé, the Faculty of Medicine, the School of Public Health and the Faculty of Motor Sciences. There is also the School of Nursing (with the Haute école libre de Bruxelles – Ilya Prigogine), the Museum of Medicine[22] and the Museum of Human Anatomy and Embryology.[23] This site is served by Erasme/Erasmus metro station.

The university also has buildings and activities in the Brussels municipality of Auderghem, and outside of Brussels, in Charleroi on the Aéropole Science Park and Nivelles.

-

Entrance of the Paul-Émile Janson Auditorium on the Solbosch campus

-

The Museum of Medicine on the Erasme/Erasmus campus in Anderlecht

Faculties and institutes

- Institute for European Studies[24]

- Interfacultary School of Bio-Engineering

- School of Public Health

- High Institute of Physical Education and Kinesiotherapy

- Institute of Work Sciences

- Institute of Statistics and Operational Research

- Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Solvay Brussels School of Economics and Management

- Faculty of Sciences

International Partnerships

University of California, Berkeley, University of Oxford, University of Cambridge, Université de Montréal, Waseda University, Université Pierre et Marie Curie - Paris VI, BeiHang University, Universidade de São Paulo, Université de Lausanne, Université de Genève, University Ouaga I Pr. Joseph Ki-Zerbo, University of Lubumbashi[25]

| Faculty or Institute | Bachelor's degrees | Master's degrees | Complementary master's degrees |

|---|---|---|---|

| Faculty of Architecture | Architecture | Architecture | |

| Faculty of Philosophy and Letters |

|

|

African Languages and Cultures |

| Pedagogy in Higher Education | |||

| Language Sciences | |||

| Art History and Archaeology | Art History and Archaeology (1 or 2 years) | ||

| Art History and Archaeology: Musicology | Art History and Archaeology: Musicology (1 or 2 years) | ||

| French and Roman Languages and Literature | Cultural Management | ||

| History | Ethics | ||

| Information and Communication | French and Roman Languages and Literature (1 or 2 years) | ||

| Modern Languages and Literature | French and Roman Languages and Literature: French Foreign Language | ||

|

History (1 or 2 years) | ||

| Philosophy | Information and Communication (1 or 2 years) | ||

| Religious and Secular Studies | Information and Communication Sciences and Technologies | ||

| Linguistics | |||

| Modern Languages and Literature (1 or 2 years) | |||

|

|||

| Multilingual Communication | |||

| Performing Arts | |||

| Philosophy (1 or 2 years) | |||

| Religious and Secular Studies | |||

| Faculty of Law and Criminological Science | Law | Criminology | Economic Law |

| Law | International Law | ||

| Notaries | |||

| Public and Administrative Law | |||

| Social Law | |||

| Tax Law | |||

| Faculty of Psychological Science, and of Education | Psychology and Educational Sciences | Educational Sciences | Pedagogy in Higher Education |

| Psychology and Educational Sciences: Speech Therapy | Psychology | Psychoanalytic Theories | |

| Speech Therapy | Risk Management and Well-being at Work | ||

|

Biology | Actuarial Science | Nanotechnology |

| Chemistry | Biochemistry and Molecular and Cellular Biology | ||

| Computer Sciences | Bioengineering: Agricultural Sciences | ||

| Engineering: Bioengineering | Bioengineering: Chemistry and Bio-industries | ||

| Geography | Bioengineering: Environmental Sciences and Technologies | ||

| Geology | Bioinformatics and Modeling | ||

| Mathematics | Biology (1 year) | ||

| Physics | Chemistry (1 or 2 years) | ||

| Sciences (Polyvalent first year) | Computer Sciences (1 or 2 years) | ||

| Environmental Sciences and Management (1 or 2 years) | |||

| Geography (1 or 2 years) | |||

| Geology (1 or 2 years) | |||

| Mathematics (1 or 2 years) | |||

| Organismal Biology and Ecology | |||

| Physics (1 or 2 years) | |||

| Statistics | |||

| Tourism Sciences and Management (1 or 2 years) | |||

| Faculty of Applied Sciences/Polytechnic School | Engineering: Bioengineering | Bioengineering: Agricultural Sciences | Conservation and Restoration of Immovable Cultural Heritage |

| Engineering: Civil | Bioengineering: Chemistry and Bio-industries | Nanotechnology | |

| Engineering: Civil Architect | Bioengineering: Environmental Sciences and Technologies | Nuclear Engineering | |

| Civil Engineering: Architectural | Transportation Management | ||

| Civil Engineering: Biomedical | Urban and Regional Planning | ||

| Civil Engineering: Chemistry and Material Science | |||

| Civil Engineering: Computer | |||

| Civil Engineering: Constructions | |||

| Civil Engineering: Electrical | |||

| Civil Engineering: Electro-mechanical | |||

| Civil Engineering: Mechanical | |||

| Civil Engineering: Physicist | |||

| Faculty of Medicine | Biomedical Sciences | Biomedical Sciences | |

| Dentistry | Dentistry | ||

| Medicine | Medicine | ||

| Veterinary Medicine | |||

| Institute of Pharmacy | Pharmaceutical Sciences | Biomedical Sciences | Clinical Biology (for pharmacists) |

| Pharmaceutical Sciences | Hospital Pharmacy | ||

| Industrial Pharmacy | |||

| Faculty of Social and Political Sciences | Human and Social Science | Anthropology | |

| Political Science | Human Resources Management | ||

| Sociology and Anthropology | Political Science (1 or 2 years) | ||

| Political Science: International Relations | |||

| Population and Development | |||

| Public Administration | |||

| Sociology | |||

| Sociology and Anthropology (1 year) | |||

| Work Science (1 or 2 years) | |||

| Solvay Brussels School of Economics and Management | Business Engineering | Business Engineering | Industrial Management and Technology |

| Economics | Economics (1 or 2 years) | Microfinance | |

| Institute of European Studies | European Studies | European Law | |

| Interdisciplinary Analysis of European Construction |

Research

At the heart of the Free University of Brussels there are at least 2000 PhD students and around 3600 researchers and lecturers who work around different scientific fields and produce cutting-edge research.

The projects of these scientists span thematics that concern exact, applied and human sciences and researchers at the heart of the ULB have been awarded numerous international awards and recognitions.

The research carried out at the ULB is financed by different bodies such as the European Research Council, the Walloon Region, the Brussels Capital Region, the National Fund for Scientific Research, or one of the foundations that are dedicated to research at the ULB; the ULB Foundation or the Erasme Funds.

Since the early 2000s, the MAPP project has started studying political party membership evolution through the time.

Rankings

| University rankings | |

|---|---|

| Global – Overall | |

| ARWU World[26] | 101–150 (2023) |

| CWUR World[27] | 211 (2020–21) |

| CWTS World[28] | 359 (2020) |

| QS World[29] | =227 (2026) |

| THE World[30] | 201–250 (2024) |

| USNWR Global[31] | =222 (2023) |

Notable people

- Count Richard Goblet d'Alviella (b. 1948), businessman

- Jules Anspach (1829–1879), politician and mayor of Brussels

- Philippe Autier (b. 1956), epidemiologist and clinical oncologist

- Zénon-M. Bacq (1903–1983), radiobiologist, laureate of the 1948 Francqui Prize

- Radu Bălescu (1932–2006), Romanian and Belgian physicist, laureate of the 1970 Francqui Prize

- Saeed Bashirtash (b. 1965), Iranian dentist, writer and political activist

- Didier Bellens (1955–2016), businessman, CEO of Belgacom

- Vincent Biruta (b. 1958), Rwandan physician and politician, Minister of Foreign Affairs

- Jules Bordet (1870–1961), physician, laureate of the 1919 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

- Karel Bossart (1904–1975), aeronautical engineer, designer of the SM-65 Atlas

- Jean Brachet (1909–1998), biochemist

- Robert Brout (1928–2011), American physicist, laureate of the 2004 Wolf Prize

- Jean Bourgain (1954–2018), mathematician, laureate of the 1994 Fields Medal

- Albert Claude (1899–1983), biologist, laureate of the 1974 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

- Heidi Cruz (b. 1972), American businesswoman, wife of U.S. Senator Ted Cruz

- Herman De Croo (b. 1937), liberal politician

- Théophile de Donder (1872–1957), physicist, mathematician, and father of irreversible thermodynamics

- Vũ Đức Đam (b. 1963), Vietnamese politician, Deputy Prime Minister

- Pierre Deligne (b. 1944), mathematician, laureate of the 1978 Fields Medal

- Antoine Depage (1862–1925), surgeon, founder and president of the Belgian Red Cross, and one of the founders of Scouting in Belgium

- Mathias Dewatripont (b. 1959), economist, laureate of the 1998 Francqui Prize

- François Englert (b. 1932), physicist, laureate of the 2004 Wolf Prize, laureate of the 2013 Nobel Prize in Physics

- Jacques Errera (1896–1977), physicochemist, laureate of the 1938 Francqui Prize

- Aleth Félix-Tchicaya (b. 1955), Congolese writer

- Louis Franck (1868–1937), lawyer, liberal politician and statesman

- Matyla Ghyka (1881–1965), Romanian poet, novelist, mathematician, historian, and diplomat

- Michel Goldman (b. 1955), immunologist

- Nico Gunzburg (1882–1984), lawyer and criminologist

- Camille Gutt (1884–1971), economist, politician, and industrialist, first Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund

- Marc Henneaux (b. 1955), physicist, laureate of the 2000 Francqui Prize

- Amir Abbas Hoveida (1919–1979), Iranian economist and politician, Prime Minister

- Enver Hoxha (1908–1985), Albanian politician, leader of Communist Albania

- Julius Hoste Jr. (1884–1954), businessman and liberal politician

- Léon Van Hove (1924–1990), physicist, laureate of the 1958 Francqui Prize, Director General of the CERN

- Paul Hymans (1865–1941), politician and first President of the League of Nations

- Paul Janson (1840–1913), liberal politician

- Bahadir Kaleagasi (b. 1966), Turkish writer, International co-ordinator of TUSIAD

- Jeton Kelmendi (b. 1978), Albanian writer, laureate of the 2010 International Solenzara Prize

- Henri La Fontaine (1854–1943), lawyer, laureate of the 1913 Nobel Peace Prize

- Roberto Lavagna (b. 1942), Argentine economist and politician, Minister of Economy and Production

- Maurice Lippens (b. 1943), businessman and banker

- Lucien Lison (1908–1984), Belgian-Brazilian physician and biochemist, considered the "father of histochemistry"

- Amer Husni Lutfi (b. 1956), Syrian politician, Minister of Economy and Trade

- Paul Magnette (b. 1971), socialist politician and political scientist, mayor of Charleroi, laureate of the 2000 Francqui Prize

- Marguerite Massart (1900–1979), first Belgian female engineer

- Adolphe Max (1869–1939), politician, mayor of Brussels

- Adrien-Jean Le Mayeur (1880–1958), painter

- Fradique de Menezes (b. 1942), São Toméan politician, President

- Françoise Meunier, doctor, Director General of the EORTC

- Charles Michel (b. 1975), politician, Prime Minister and President of the European Council

- Constantin Mille (1861–1927), Romanian socialist militant and journalist

- Axel Miller (b. 1965), businessman, CEO of Dexia

- Roland Mortier (1920–2015), philologist, laureate of the 1965 Francqui Prize

- François Narmon (1934–2013), economist and businessman, President of Dexia and the Belgian Olympic Committee

- Amélie Nothomb (b. 1967), writer, laureate of the 1999 Grand Prix du roman de l'Académie française

- Enrique Olaya Herrera (1880–1937), Colombian journalist and politician, President

- Paul Otlet (1868–1944), author, entrepreneur, lawyer and peace activist, founding father of documentation

- Henri De Page (1894–1969), jurist, Professor in Law, generally seen as the most important Belgian lawyer ever

- Marc Parmentier (b. 1956), scientist, laureate of the 1999 Francqui Prize

- Etienne Pays (b. 1948), molecular biologist, laureate of the 1996 Francqui Prize and of the Carlos J. Finlay Prize for Microbiology

- Robert Peston (b. 1960), British journalist, presenter, and author, ITV News Political Editor

- Martine Piccart (b. 1953), medical oncologist, President of the EORTC

- Marie Popelin (1846–1913), jurist and feminist

- Ilya Prigogine (1917–2003), physicist and chemist, laureate of the 1955 Francqui Prize and of the 1977 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

- Lodewijk De Raet (1870–1914), economist and politician

- Eric Remacle (1960–2013), economist, laureate of the 2000 Francqui Prize

- Jan Van Rijswijck (1853–1906), lawyer, liberal politician and journalist, mayor of Antwerp

- David Ruelle (b. 1935), Belgian-French mathematical physicist

- Pedro Sánchez (b. 1972), Spanish politician, Prime Minister

- Jean Auguste Ulric Scheler (1819–1890), philologist

- Paul-Henri Spaak (1899–1972), politician, statesman, Prime Minister, Secretary General of NATO, and one of the Founding fathers of the European Union

- Isabelle Stengers (b. 1949), philosopher

- Jean Stengers (1922–2002), historian

- Jacques Tits (1930–2021), Belgian-French mathematician, laureate of the 1993 Wolf Prize and of the 2008 Abel Prize

- Michel Vanden Abeele, diplomat, Director-General of the European Commission

- Raoul Vaneigem (b. 1934), writer and Situationist theorist

- Emile Vandervelde (1866–1938), statesman, socialist leader, Minister of Justice, and Minister of Foreign Affairs

- Adamantios Vassilakis (1942–2021), Greek ambassador to the United Nations

- August Vermeylen (1872–1945), writer and literature critic

- Éliane Vogel-Polsky (1926–2015), lawyer and feminist

- Raoul Warocqué (1870–1917), industrialist

- Charles Woeste (1837–1922), lawyer and politician

- Odette De Wynter (1927–1998), first woman to be a notary in Belgium

Nobel Prize Winners

For pre-1970 notable faculty and alumni, see Free University of Brussels:

- Ilya Prigogine (1917–2003): Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1977

- François Englert (b. 1932): Nobel Prize in Physics in 2013

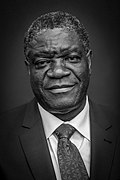

- Denis Mukwege (b. 1955): Nobel Peace Prize in 2018

-

Denis Mukwege, Nobel Peace Prize (2018)

Controversy

Inspired by US protests on university campuses,[32] on 7 May 2024, around a hundred students occupied a university building,[33][34] which they named in honour of Walid Daqqa, a member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine,[35][36][34] while demanding the release of the leader of the Lebanese Revolutionary Armed Faction, Georges Abdallah, from a French prison.[37] The same year, Jewish students reported antisemitic and anti-Zionist insults, vandalism of posters against antisemitism, as well as cases of students being violently attacked.[36][38][39] A passer-by who allegedly declared herself a Zionist was also attacked.[40] The Simon Wiesenthal Center views this as a trend towards antisemitism in Belgian academic circles.[41] Critics have accused the protesters of extremism, however, the Coordinating Body for Threat Analysis did not find any "structural or hierarchical link" with extremist groups.[42]. Notably, French journalist Nora Bussigny claimed in her book "Les nouveaux antisémites"(The new anti-Semites), that she "discovered a more structured and persistent radicalization than at other universities".[43] In November, a declaration targeting the "Zionists" of Brussels and Europe,[42] led the Jonathas Institute, a centre for studies and action against antisemitism in Belgium, to file a complaint against the student group, for inciting hatred and violence.[44]

In August 2025, the Faculty of Law decided to honour the French politician Rima Hassan as a symbolic gesture.[45][46][47] The Belgian League Against Antisemitism criticised the decision, citing Hassan's controversial comments on the "legitimacy" of the antisemitic massacre,[48] as did 50 French intellectuals, given that Hassan is facing charges for incitement to terrorism in France.[45][49] The Minister-President of the French Community, Élisabeth Degryse, also expressed her opposition.[50] Hassan and ULB students celebrated the decision by chanting in favor of armed conflict: "Long live the armed struggle of the Palestinian people".[51] In December, the university awarded two ULB researchers, among others, with a Science Dissemination Prize.[52] The first, François Dubuisson, has portrayed the 7 October attacks as an attempt by Hamas to "break the lines", for which he was criticised by members of the Belgian political class.[53] The latter, Déborah Brosteaux, has also faced criticism for her pro-Palestinian views.[54]

In front of the European Parliament, Céline Imart of the French political party The Republicans has requested the European Commission to suspend aid for the university: "Ask the Commission to immediately suspend the funds allocated to this university, until the safety of Jewish students is guaranteed and the values of the Union are once again respected".[55] Members of the Belgian political party Reformist Movement have also voiced their concerns.[56] Facing renewed criticism in September,[57] the rector, Annemie Schaus, denied allegations of antisemitism against the university.[58] In contrast, university professors have described antisemitism as "rapidly taking hold on ULB campuses since 7 October".[37] Jewish students have voiced their fear of being targeted, describing the hostility on campuses as "significant".[59][60] At the Working Group Against Antisemitism of the European Parliament, the Jonathas Institute warned of "an environment in which antisemitism goes largely unchallenged".[61]

Florida has placed the university on its blacklist for its "boycott" of Israel.[62][63] Instead of ties with Israeli universities, the university has established ties with the Palestinian Birzeit University, despite its support for Hamas in student elections,[47] while maintaining its relations with other universities of autocratic regimes.[64] The Belgian Jewish organization Forum der Joodse Organisaties criticized what it sees as political moves against the academic and scientific networks, concerning Jews and Israelis.[65] Other critics have argued that it constitue a discrimination and a violation of academic principles.[66] According to the university, the "suspension" of partnerships and agreements is related to the war in Gaza, as such, the university put forward the allegation of not "complying" to a remark of the International Court of Justice addressed to Israeli universities.[67] At the same time, pro-Palestinian student groups have protested against ties with "Zionist elements",[68] and some of them against the "Zionist entity".[69] According to the International League Against Racism and Anti-Semitism, the anti-Zionism by members of the university in their support of Palestinian nationalism or boycott, violated the IHRA definition of antisemitism adopted notably by the Senate.[64]

See also

- List of split up universities

- Science and technology in Brussels

- Top Industrial Managers for Europe

- Atomium Culture

- Institut Jules Bordet

- Royal Statistical Society of Belgium

- University Foundation

Notes and references

Footnotes

- ^ lit. 'University of Brussels'. (This Latin name is also used by other institutions, including the Vrije Universiteit Brussel.)

- ^ The split occurred along linguistic lines, forming the French-speaking ULB in 1969, and Dutch-speaking Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB) in 1970.

Citations

- ^

- Chiffres de la rentrée 2023–2024: Étudiantes et étudiants par université et par secteur d'études [Figures for the 2023–2024 academic year: Students by university and by sector of study] (in French), Le Conseil des rectrices et recteurs, Note: Situation provisoire fin février 2024. Les données sont susceptibles d'évoluer d'ici la fin de l'année académique. [Provisional situation at the end of February 2024. The data is likely to change by the end of the academic year.], archived from the original on 6 May 2024, retrieved 13 April 2024

- "Annuaires Statistiques Données statistiques les plus récentes". Le Conseil des rectrices et recteurs (in French). Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ a b c d Witte, Els (1996). Pierre-Théodore Verhaegen (1796–1862) (in Dutch). ISBN 90-5487-140-7.

- ^ ULB Bureau d'Études (June 2012), Statistiques et Études Prospectives – Population étudiante 2011–2012 par domaines études, nationalité, genre (PDF) (in French), Université libre de Bruxelles, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 June 2013, retrieved 4 September 2013

- ^ a b "A University born of an idea". Université libre de Bruxelles. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ^ Lamberts, Emiel; Roegiers, Jan (1990). Leuven University, 1425–1985. Leuven: Leuven University Press. ISBN 90-6186-418-6.

- ^ "Pierre Théodore Verhaegen and St V". Vrije Universiteit Brussel. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ "A short history of Saint-Louis". www.usaintlouis.be. Retrieved 7 December 2025.

- ^ Laqua, Daniel (2013). The Age of Internationalism and Belgium, 1880–1930: Peace, Progress and Prestige. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-8883-4.

- ^ Great Britain's first home Olympic football adventure by Jon Carter, ESPN, 26 Jun 2012

- ^ Before the World Cup: Who were football's earliest world champions? by Paul Brown on Medium Sports, 6 Jun 2018

- ^ Games of the II. Olympiad - Football Tournament by Søren Elbech and Karel Stokkermans on the RSSSF

- ^ Nerincx, Edmond (8 November 1911). Loi du 12 août 1911 accordant la personnification civile aux universités de Bruxelles et de Louvain (PDF) (in French). Brussels: Belgian official journal. p. 4846. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Steinberg, Maxime (1998). "Chapter 4. L'université du libre-examen et ses juifs". Un pays occupé et ses juifs, La Belgique, entre France et Pays-Bas (in French). Brussels: Editions de l'Université de Bruxelles.

- ^ Aron, Paul; Gotovitch, José (2008). Dictionnaire de la Seconde Guerre mondiale en Belgique (in French). Bruxelles: Editions André Versaille. ISBN 9782874950018.

- ^ "A Brief – History of Belgian Resistance". Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ^ "About the University: Culture and History". Vrije Universiteit Brussel. Archived from the original on 16 June 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2007.

- ^ Jonckheere, Willy; Todts, Herman (1979). Leuven Vlaams: Splitsingsgeschiedenis van de Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (in Dutch). Leuven: Davidsfonds. ISBN 9061523052.

- ^ "Chambre des Représen tant" (PDF).

- ^ "Law of 28 May 1970, concerning the splitting of the universities in Brussels and Leuven" (in Dutch). Belgisch Staatsblad/Flemish Government. Retrieved 25 November 2007.

- ^ "Muséum de Zoologie et d'Anthropologie". www2.ulb.ac.be. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ "Université Libre de Bruxelles - page 3". www2.ulb.ac.be. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ "Musée de la Médecine de Bruxelles". Musée de la médecine. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ "Musée d'Anatomie et d'Embryologie humaines - page 2". www2.ulb.ac.be. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ "Home". www.iee-ulb.eu. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ^ "Les relations internationales de l'ULB". www.ulb.ac.be. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ^ "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2020". ShanghaiRanking. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2024.

- ^ "World University Rankings 2020-2021". Center for World University Rankingsg. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ "CWTS Leiden Ranking 2020 - P(top 10%)". CWTS Leiden Ranking. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings".

- ^ "World University Rankings 2024 - Université libre de Bruxelles". Times Higher Education (THE). Retrieved 7 March 2024.

- ^ "Best Global Universities 2022-23 - Université Libre de Bruxelles". U.S. News Education (USNWR). ). Retrieved 7 March 2024.

- ^ "For Campus Protesters in Brussels, Familiar Methods, but Different Outcomes". New York Times. 21 June 2024. Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ "Des étudiants occupent le campus de l'ULB pour dénoncer le « génocide en cours à Gaza » (vidéo)". Le Soir (in French). 7 May 2024. Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ a b "Pro-Palestine student occupation spreads to ULB". www.brusselstimes.com. 7 May 2024. Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ Louazon, Elena (10 May 2024). "A Bruxelles, des étudiants propalestiniens s'opposent à la tenue d'un débat avec Elie Barnavi" (in French). Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ a b Bosco d'Otreppe (6 October 2025). "Vandalisme, violence, injures : de jeunes étudiants témoignent de graves intimidations et faits d'antisémitisme ces derniers mois à l'ULB". La Libre.be (in French). Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ a b "« Le syndrome du déni d'antisémitisme est présent à l'ULB » (carte blanche)". Le Vif (in French). 15 May 2024. Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ Oschinsky, Marc. "'Ici, le mot Juif dérange' : une campagne choc (mais invisible) sur le campus de l'ULB - RTBF Actus". RTBF (in French). Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ "Des affiches dénonçant l'antisémitisme arrachées à l'ULB : "L'Université ignore volontairement les réalités que nous vivons"". DHnet (in French). 18 December 2025. Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ "Fin de la procédure disciplinaire à l'encontre d'un étudiant de l'ULB pour antisémitisme - RTBF Actus". RTBF (in French). 1 December 2025. Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ "SWC Highlights Alarming Rise in Anti-Semitism in Belgium Since October 7th". wiesenthal.org. 15 July 2024. Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ a b "Des mouvements propalestiniens belges sous surveillance". L'Echo (in French). 14 November 2024. Archived from the original on 20 October 2025. Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ Bussigny, Nora (19 December 2025). "L'antisémitisme est plus radical à l'ULB que sur les campus français ou américains". L'Echo (in French). Retrieved 17 January 2026.

- ^ "Plainte contre le mouvement étudiant anti-Israël « Université Populaire de Bruxelles »". Times of Israel (in French). 12 November 2024. Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ a b "Une promotion Rima Hassan confirmée à l'Université libre de Bruxelles". Le Monde (in French). 28 August 2025. Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ "Rima Hassan, la polémique dont l'ULB se serait passée". Le Soir (in French). 25 August 2025. Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ a b Heller, Mathilda (31 August 2025). "Anti-Israel LFI politician Rima Hassan named as Brussels Free U class patron". TheJerusalemPost. Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ De Barochez, Luc (6 September 2025). "Joël Rubinfeld : "Nous sommes la dernière génération juive à vivre en Belgique"". L'Express (in French).

- ^ "Rima Hassan : 50 intellectuels déplorent le choix des étudiants en droit de l'ULB". La Libre.be (in French). 16 September 2025. Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ Zveny, Zhen-Zhen (16 September 2025). "Promotion Rima Hassan à l'ULB : "Je ne suis pas d'accord avec le choix qui a été fait", déclare la ministre-présidente Elisabeth Degryse". DHnet (in French). Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ Bussigny, Nora (19 December 2025). "L'antisémitisme est plus radical à l'ULB que sur les campus français ou américains". L’Echo (in French). Retrieved 1 January 2026.

- ^ Gobbe, Nathalie. "Prix de la diffusion scientifique ULB: les lauréats et lauréates 2025". Actualités de l'ULB (in French). Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ Michael Bouche (9 October 2023). "François Dubuisson, prof ULB: "C'est abject" L'interview du professeur crée un vif débat". 7sur7 (in French). Norbert Digital. Retrieved 12 December 2025.

- ^ Geerts, Nadia (8 December 2025). "À l'université libre de Bruxelles, mieux vaut être radicalement pro-palestinien que juif". Marianne (in French). Retrieved 12 December 2025.

- ^ Furfari, Samuel (4 September 2025). "ULB : de l'idéal du libre examen à la soumission communautariste". Atlantico (in French). Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ Vanhemelen, Emilie (9 May 2024). "Clémentine Barzin (MR) plaide pour la mise en place du métro à Uccle et à Ixelles". BX1 (in French). Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ Burgraff, Eric; Hutin, Charlotte (14 September 2025). "Annemie Schaus, rectrice de l'ULB : « La violence et les invectives n'ont plus de limite… un peu à l'image de la société »". Le Soir (in French).

- ^ ""Non, l'ULB n'est pas bienveillante à l'antisémitisme", dit la rectrice Annemie Schaus". DHnet (in French). 19 September 2025. Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ Zveny, Zhen-Zhen (18 December 2025). "Le conflit israélo-palestinien s'invite à l'ULB: "Je ne suis plus en sécurité sur le campus parce que je suis juif"". La Libre.be (in French). Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ Thaidigsmann, Michael (26 August 2025). "Europäische Unis sind Hotspots des Judenhasses". Jüdische Allgemeine (in German). Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ "WGAS organises conference in the European Parliament on the dramatic rise of antisemitism in European universities". ep-wgas.eu. 8 September 2025. Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ "Florida blacklists Belgian universities due to their position on Gaza | VRT NWS: news". VRTNWS. 20 October 2025. Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ Ducrotois, Martin (18 October 2025). "La Floride place des universités belges sur liste noire en raison du boycott d'Israël". 7sur7 (in French). Retrieved 18 December 2025.

- ^ a b "La lente descente aux enfers de l'Université libre de Bruxelles". Le Droit de Vivre (in French). LICRA (Ligue internationale contre le racisme et l'antisémitisme). 7 January 2026. Retrieved 11 January 2026.

- ^ "Forum der Joodse Organisaties roept universiteiten op Israëlische boycot af te wijzen". BRUZZ (in Dutch). BRUZZ. 12 January 2025. Retrieved 13 January 2026.

- ^ "Guerre Israël-Gaza : les recteurs des universités belges doivent adopter une politique de neutralité institutionnelle". Le Soir (in French). 8 July 2025. Retrieved 17 January 2026.

- ^ "University of Antwerp and ULB pause cooperation agreements with Israeli partners". Belga News Agency. Belga News Agency. 28 May 2024. Retrieved 13 January 2026.

- ^ אסף אוני (15 May 2024). "Belgium and the Netherlands in Academic Boycott of Israel, and the Billion-Program at Risk". גלובס (in Hebrew). Globes. Retrieved 14 December 2025.

- ^ Lachapelle, Aurélie (11 December 2025). "Incursion dans une université qui boycotte Israël… ou presque". Montreal Campus (in French). Retrieved 14 December 2025.

Further reading

- Despy, A., 150 ans de L'ULB. Université libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, 1984

- Noel, F., 1894. Université libre de Bruxelles en crise, Brussels, 1994

External links

![]() Media related to Université libre de Bruxelles at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Université libre de Bruxelles at Wikimedia Commons