Osama bin Laden

Osama bin Laden | |

|---|---|

أسامة بن لادن | |

Bin Laden, c. 1997–1998 | |

| 1st General Emir of al-Qaeda | |

| In office 11 August 1988 – 2 May 2011 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Ayman al-Zawahiri |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Osama bin Mohammed bin Awad bin Laden 10 March 1957 Riyadh, Saudi Arabia |

| Died | 2 May 2011 (aged 54) Abbottabad, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wounds to the head and chest |

| Resting place | Arabian Sea |

| Citizenship |

|

| Spouses | Khadijah Sharif

(m. 1983; div. 1990)Khairiah Sabar (m. 1985)Siham Sabar (m. 1987)Amal Ahmed al-Sadah (m. 2000) |

| Children | Around 20 to 26, including Abdallah, Saad, Omar, and Hamza |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Bin Laden family |

| Education | King Abdulaziz University (BBA) |

| Religion | Sunni Islam[1][2][3][4] |

| Jurisprudence | Hanbali |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Years of service | 1984–2011 |

| Rank | General Emir of al-Qaeda |

| Battles/wars | |

Osama bin Mohammed bin Awad bin Laden[a] (10 March 1957 – 2 May 2011) was the founder and first general emir of the al-Qaeda militant organization. A pan-Islamist and Islamic extremist, bin Laden organized and funded numerous jihadist or anti-Western militants and terrorist attacks worldwide. Al-Qaeda's September 11, 2001 attacks (9/11) against the United States killed 2,977 victims.

He aided the Afghan mujahideen in the Soviet–Afghan War (1979–1989), and then the Bosnian mujahideen in the Bosnian War (1992–1995). He played in role in starting both the Algerian Civil War (1992–2002), in which he aided the GSPC, and the War in Afghanistan (2001–2021), in which he aided the Taliban. Al-Qaeda in Iraq, later named the Islamic State of Iraq, fought in the Iraq War (2003–2011).

Bin Laden was raised into Sunni Islam in Saudi Arabia. His family was wealthy, having financial ties to the country's royal House of Saud. In 1979, he left to help mujahideen repel the Soviet Union's invasion of Afghanistan, and in 1984, co-founded Maktab al-Khidamat to recruit foreigners into the rebellion. In 1988, bin Laden founded al-Qaeda to enact violent jihad worldwide. The Soviets withdrew from Afghanistan in 1989, and he returned to Saudi Arabia. Bin Laden's public beliefs led to his expulsion from Saudi Arabia in 1991. He then moved with al-Qaeda to Sudan. In 1996, Sudan also expelled him, and he moved al-Qaeda to Afghanistan, which soon came under Taliban control.

After the Gulf War (1990–1991), Saudi Arabia allowed American troops to station within Saudi borders for years. This led to bin Laden's 1996 declaration of war on the majority-Christian U.S.; he viewed Muhammad as having banned infidels of Islam from permanently staying in Arabia. Al-Qaeda bombed the World Trade Center in New York City in 1993, U.S. embassies in Africa in 1998, and USS Cole in Yemen in 2000. 9/11 was mainly planned by bin Laden and Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, and they may have been aided by Saudi Arabia. After the attacks, as bin Laden lived in Afghanistan, an international manhunt for him began. The U.S. invaded the country and deposed its Taliban government, forcing him to move to Pakistan.

In 2011, U.S. troops killed bin Laden at his compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, and Ayman al-Zawahiri succeeded him as al-Qaeda's emir. Many Islamists consider bin Laden heroic for supporting rebellions and terrorist attacks in the name of Islam, while elsewhere, he is seen as a symbol of terrorism and mass murder.

Names

Bin Laden's name is most frequently rendered as "Osama bin Laden". During his life, U.S. intelligence internally referred to him as "Usama bin Laden", acronymizing it as "UBL". His last name has also been spelled "bin Ladin".[6][7] Bin, also spelled ibn, means "son of" in Arabic.[8] His full name, Osama bin Mohammed bin Awad bin Laden, thus means "Osama, son of Mohammed, son of Awad, son of Laden".[9] "Mohammed" refers to his father Muhammad bin Ladin,[10] whose full name was "Muhammad bin Awad bin Laden".[11]

At birth, bin Laden was named Usama, meaning "lion", after Usama ibn Zayd, one of the companions of Muhammad.[12] Later in life, bin Laden assumed the kunya (teknonym) Abū ʿAbdallāh, meaning "father of Abdallah", his son. The Arabic linguistic convention would be to refer to Osama as "Osama" or "Osama bin Laden", not "bin Laden" alone, as "bin Laden" is a patronymic surname, not a surname in the Western manner.[13] In the West, he is nonetheless nicknamed "bin Laden", which often begins sentences about him—"Bin Laden effusively praised the Jordanian-born militant"—although, being at the start of a sentence, ibn would be more accurate to Arabic—"Ibn Laden effusively [...]".[8] According to his son Omar, the family's hereditary surname is āl-Qaḥṭānī, but Muhammad bin Ladin never officially registered the name.[13]

According to the FBI, in his life, Osama also used the aliases Osama bin Muhammad bin Laden, Shaykh Osama bin Laden, Mujahid Shaykh, the Prince, the Emir, Hajj, and the Director.[6] A shaykh or sheikh is an older man of authority.[14] A mujahid, plural mujahideen, is someone who engages in jihad (struggle in the name of Islam, peaceful or violent).[15] An emir is a military or political commander.[16] Hajj is the traditional pilgrimage of Muslims to the holy city of Mecca, Saudi Arabia.[17]

Several news outlets have confused Osama's name with that of Barack Obama, U.S. president from 2009 to 2017.[18] In 2011, The Washington Post and BBC News, among many others, published reports on bin Laden's death that referred to him as "Obama bin Laden".[19][18] The similarity of their names is likely a key reason behind conspiracy theories that Obama is an Islamic extremist.[20]

Early life

Osama bin Laden was born on 10 March 1957 in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.[21][22] Despite it being generally accepted that his birthplace was Riyadh, FBI and Interpol documents formerly listed it as Jeddah.[23] He was part of the bin Laden family, based in Saudi Arabia, who were incredibly successful in the construction industry; he later inherited from them around $25–30 million in 2011 USD.[24] Bin Laden's father Muhammad was born in Yemen, and became a billionaire off of his work in construction. He had close ties to the Saudi royal family, the House of Saud. Osama's mother Hamida al-Attas was from Syria, and was Muhammad's tenth wife.[25][26][27] Osama was the 17th of Muhammad's 52 children.[28]

Muhammad divorced Hamida soon after Osama was born. Hamida then married Muhammad's associate, Mohammed al-Attas, in the late 1950s or early 1960s.[29] They had four children, and bin Laden lived in the new household with three half-brothers and one half-sister.[25]

Bin Laden was raised into Sunni Islam.[30] From 1968 to 1976, he attended the prestigious Al-Thager Model School in Jeddah.[25][31] He attended an English-language course in Oxford, England, in 1971.[32] He studied economics and business administration at King Abdulaziz University in Jeddah.[33][34] One source described him as "hard working";[35] another said he left university during his third year, without attaining a college degree.[36] At university, bin Laden's main interest was religion. He studied the Quran and jihad, and did charity work.[37] Other interests included writing poetry; reading, reportedly favoring the works of Bernard Montgomery and Charles de Gaulle; black stallions; and association football, in which he enjoyed playing centre forward. He also followed the English football club Arsenal.[38][39] In Jeddah, bin Laden was taught by influential Islamist scholar Abdullah Yusuf Azzam, and avidly read his treatises. He also read works of several Muslim Brotherhood leaders, and was highly influenced by the radical Islamism advocated by Egyptian revolutionary Sayyid Qutb.[40] Some reports suggest that bin Laden earned a degree in civil engineering in 1979,[41] or a degree in public administration in 1981.[34]

Personal life

At age 17 in 1974, bin Laden married Najwa Ghanem in Latakia, Syria.[42] They separated prior to 2002.[43] His other known wives were Khadijah Sharif (married 1983, divorced 1993); Khairiah Sabir (married 1985); Siham Sabir (married 1987); and Amal al-Sadah (married 2000). Some sources also list a sixth wife of an unknown name, whose marriage to bin Laden was annulled soon after the ceremony.[44] Bin Laden fathered 24 children with his wives.[45] Many of his children fled to Iran following the 11 September 2001 attacks, which he perpetrated, and as of 2010, Iran closely controlled them there.[46] Nasser al-Bahri, bin Laden's bodyguard from 1997 to 2001, described him as a frugal man and a strict father, who enjoyed taking his family on shooting trips and picnics in the desert.[47]

Muhammad bin Laden died in 1967 in an airplane crash in Saudi Arabia, when his pilot misjudged a landing.[48][49] Bin Laden's eldest half-brother, Salem bin Laden, was killed in 1988 in Texas, when he accidentally flew a plane into power lines.[50]

The FBI described adult bin Laden as thin, between 1.93 m (6 ft 4 in) and 1.98 m (6 ft 6 in) in height, and weighing about 73 kilograms (160 lb);[51] journalist Lawrence Wright writes that a number of bin Laden's close friends said he was actually "just over 6 feet (1.8 m) tall".[52] After his death, he was measured to be roughly 1.93 m (6 ft 4 in).[53] Bin Laden was left-handed, usually walking with a cane. He wore a plain white keffiyeh, and at one point he stopped wearing the traditional Saudi male keffiyeh and instead wore the traditional Yemeni male keffiyeh.[54] He was described as soft-spoken and mild-mannered in demeanor.[55]

Religious and political views

Islam, Muslim countries, and systems of government

Bin Laden's beliefs, and his actions as head of the militant organization al-Qaeda, had him designated as a terrorist by Western scholars,[56][57] journalists,[58][59][60] and intelligence analysts.[61][62][63] Bin Laden subscribed to the Athari school of Islamic theology, which interprets the Quran literally, rather than figuratively.[64] While he led al-Qaeda, it organized Islamic ideology classes that listed four principal enemies of Islam: Shia Muslims, heretics of Islam, the U.S., and Israel.[65] Bin Laden believed that the Islamic world was in crisis due to these groups' proliferation in the Middle East, and that only the complete restoration of Sharia law in Muslim countries would set things right; he rejected other types of government as possible solutions, such as secularist, pan-Arabist, socialist, communist, and democratic systems.[66][67] In his 2002 Letter to the American People, bin Laden called upon Americans to convert to Islam and reject fornication, homosexuality, intoxicants, gambling, and usury.[66] Researcher Dale Eikmeier sees these combined beliefs as bin Laden being adherent to the Sunni ideology Qutbism, named after Sayyid Qutb.[68]

He once denounced democracy as a "religion of ignorance" that violates Islam by issuing man-made laws, instead of those made by God.[69] Political analyst Max Rodenbeck wrote in response: "Evidently, [bin Laden] has never heard theological justifications for democracy, [which are] based on the notion that the will of the people must necessarily reflect the will of an all-knowing God."[69] In one instance, Bin Laden also favorably compared Spain's democratic system to certain non-democracies in the Muslim world, praising both as allowing for their rulers to be held accountable by the law.[69]

Attacking the United States

In organizing terrorist attacks against the U.S., bin Laden was motivated by revenge for U.S. foreign policies that killed and oppressed Muslims in the Middle East,[70] particularly those that killed women and children.[71] He believed violent jihad was needed to right such injustices.[72] He also took the permanent stationing of U.S. troops in Saudi Arabia as a provocation to all Muslims, interpreting Muhammad as having banned the "permanent presence of infidels [of Islam]", or kafir, "in Arabia";[73][74] he issued a fatwa in 1996 declaring war against the U.S. for mainly this reason.[75]

Bin Laden did not ambiguously take responsibility for 9/11 until a 2004 video, but implied his motives for the attacks before then.[76] In his 2002 letter, he described the 1948 formation of the State of Israel as "a crime which must be erased";[77][78] he viewed Israelis as kafir, and condemned Israel for oppressing and killing Muslims in Palestine with American funding and arms.[79][80] Bin Laden believed that the U.S. and United Kingdom were being directed by Israel to kill as many Muslims as possible, in service of the Israeli state's goals; Israel, having already invaded multiple Muslim countries, was alleged to be striving towards "Greater Israel" by annexing the rest of the Middle East and enslaving the annexed population.[81][82] In a video released in December 2001, he said:[83][84]

"It has become clear that the West in general and America in particular have an unspeakable hatred for Islam. [...] It is the hatred of crusaders. Terrorism against America deserves to be praised because it was a response to injustice, aimed at forcing America to stop its support for Israel, which kills our people."

In his 2002 letter, multiple factors were implied to have motivated 9/11, including U.S. support of: Israel, against Lebanon during their occupation of Southern Lebanon, and against Palestinians during the Second Intifada; the Philippines, against Muslim militants; Russia, against Muslim militants; and India's oppression of Muslims in Kashmir. He also listed the former U.S.-led intervention against Muslim militants in Somalia, pollution caused by the U.S., and the U.S.' refusal to ratify the Kyoto Protocol.[85][86][87]

Before 9/11, he believed that sending a message to the U.S. through attacks could ultimately deter its troops from targeting Muslims in the future.[71] After 9/11, when the U.S. declared its "war on terror" and began hunting al-Qaeda members, bin Laden decided to try and lure the U.S. military into a long war of attrition in Muslim countries, while he would attract large numbers of jihadists that would never surrender. He predicted this would lead to the economic collapse of the U.S., as he said, by "bleeding America to the point of bankruptcy". He noted in 2004 that this was essentially how his soldiers had help forced the Soviet Union to retreat from Afghanistan at the end of the Soviet–Afghan War (1979–1989).[88][89] In the 2001 video, he said:[83][84]

"We say that the end of the United States is imminent, whether bin Laden or his followers are alive or dead, for the awakening of the Muslim ummah [nation] has occurred. [...] It is important to hit the economy [of the U.S.], which is the base of its military power."

Attacking civilians on 9/11

In his 1996 fatwa, bin Laden mentioned that his war against the U.S. would "not differentiate between [Americans] dressed in military uniforms, and civilians; they are all targets of this fatwa".[75] Legal scholar Noah Feldman writes: "[Bin Laden believed that] since the United States is a democracy, all citizens bear responsibility for its government's actions, and civilians are therefore fair targets."[90] He also felt this was the case due to Americans paying taxes that fund their military.[71] In contrast, he once stated that American democracy was "the law of the rich and wealthy".[91] In a 1998 interview with American journalist John Miller, he stated:[92]

"American history does not distinguish between civilians and military, not even women and children. They are the ones who used bombs against Nagasaki. Can these bombs distinguish between infants and military? America does not have a religion that will prevent it from destroying all people. [...] This is my message to the American people: to look for a serious government that looks out for their interests and does not attack others, their lands, or their honor."

After 9/11, bin Laden claimed that the attacks' targets "were not women and children", saying Muhammad was against killing them; instead, "the main targets were the symbol of the United States: their economic and military power". "Economic" referred to the World Trade Center, a business complex in New York City, and "military" referred to the Pentagon, the headquarters of the U.S. Department of Defense, in Virginia.[93][94] In 2004, he said he had been inspired to target the World Trade Center's "Twin Towers"—1 and 2 World Trade Center, or the North and South Towers, respectively—as revenge for the destruction of towers by U.S.-backed Israeli troops during the siege of Beirut, Lebanon, in the 1982 Lebanon War.[95][96]

"God knows it did not cross our minds to attack the towers [at first], but after [witnessing] the destroyed towers in Lebanon, it occurred to me punish the unjust the same way: to destroy towers in America, so it could taste some of what we are tasting, and to stop killing our children and women."[97]

Judaism

Bin Laden was heavily anti-Semitic.[81] He stated that most of the negative events that occurred in the world were the direct result of Jewish actions,[82] and that Jews and Muslims could never get along, as war was "inevitable" between them.[81] In his 2002 letter, he stated that Jews controlled American media outlets, politics, and economic institutions.[66] The U.S. and U.K.'s governments were also alleged to be under their control, and he mentioned Operation Desert Fox as proof of this.[81][82] Bin Laden once described the Jews in this supposed conspiracy as "masters of usury [and] treachery, [who] will leave you nothing, either in this world or the next."[98] He said in his 1998 interview:[92]

"So we tell the Americans as people, and we tell the mothers of soldiers and American mothers in general, that if they value their lives and the lives of their children, to find a nationalistic government that will look after their interests and not the interests of the Jews."

Deaths of Muslim civilians

Al-tatarrus is an Islamic doctrine which denies—in certain circumstances—that Muslims engaged in a military conflict, whose actions unintentionally caused civilian deaths, had acted immorally. In 2010, bin Laden wrote a letter chastising followers of his—such al-Qaeda's ally, Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan—who had interpreted al-tatarrus to justify routine massacres of Muslim civilians, which had turned away many Muslims that were previously supportive of Islamist jihadism. Around this time, he ordered the creation of a code of conduct that would constrain allied jihadists' miltiary activities to avoid civilian deaths. He also instructed his followers around the world to focus on persuading hesistant Islamic poltical parties to follow Islamist jihadism, instead of fighting them. He urged his allies in Yemen to negotiate an end to their conflict with other Muslims, or at least demonstrate peaceful intentions to Yemeni Muslims. Furthermore, he urged the allied Somalian militant group al-Shabab to pursue economic development in their country, to reduce the extreme poverty that constant warfare had caused there.[99]

Other beliefs

Bin Laden was opposed to music on religious grounds,[100] and his attitude towards technology was varied. He was interested in earth-moving machinery and genetic engineering of plants, while rejecting the use of chilled water.[101] He also believed climate change to be a serious threat to humanity, and once penned a letter to the American public (which was released posthumously) urging them to work with Barack Obama to prevent further climate change, and "save humanity from the harmful gases that threaten its destiny".[102][103]

Militant and political career, 1979–2001

Soviet–Afghan War

After leaving college in 1979, bin Laden went to Pakistan with Abdullah Yusuf Azzam, and used money and machinery from his own construction company to help the Afghan mujahideen resistance in the Soviet–Afghan War.[104] He later told a journalist: "I felt outraged that an injustice had been committed against the people of Afghanistan."[105]

From 1979 to 1992, the U.S. (as part of Operation Cyclone), Saudi Arabia, and China provided between $6–12 billion worth of financial aid and weapons to tens of thousands of fighters in the Afghan mujahideen through Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI).[106]

Bin Laden became acquainted with Hamid Gul, a three-star general in the Pakistani Army and head of the ISI. Although the U.S. provided the mujahideen money and weapons, the militants' training was entirely done by the Pakistan Armed Forces and the ISI.[107] Contrary to popular belief, the U.S. did not train or fund bin Laden's followers directly.[108] However, bin Laden himself was trained by U.S. special forces commando Ali Mohamed.[109] According to Brigadier Mohammad Yousaf, then-head of ISI's Afghanistan operations, Pakistan had a strict policy to prevent any American funding, arming, or training of mujahideen.[110]

According to some CIA officers, beginning in early 1980, bin Laden acted as a liaison between the Saudi General Intelligence Presidency (GIP) and Afghan warlords. Journalist Steve Coll states that while bin Laden was likely not a salaried GIP agent, "it seems clear [that they] did have a substantial relationship."[111]

In 1984, bin Laden and Azzam founded Maktab al-Khidamat (MaK), which funneled money, arms, and fighters from across the Arab world into the Afghan mujahideen.[112] Bin Laden's funded it with his inheritance of his family's fortune. MaK paid for fighters' flight tickets and other travel services.[113][112] He established camps inside Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province in Pakistan, and trained his volunteers to fight the Soviets and the Soviet-backed regime. Between 1986 and 1987, he set up a base in eastern Afghanistan for several dozen of his own soldiers.[112] There, bin Laden participated in some combat against the Soviets, such as the Battle of Jaji in 1987.[112] Despite its little significance to the mujahideen war effort, the battle was lionized in the mainstream Arab press.[112] It was during this time that he became idolized by many Arabs.[114]

Allegation of involvement in 1988 Gilgit massacre

In May 1988, large numbers of Shia civilians from and around Gilgit, Pakistan, were massacred and raped by Sunni militants.[115][116] This came after a local dispute between Sunni and Shia civilians over the latter's celebrations of the Islamic holiday Eid al-Fitr, which marks the end of the holy month of Ramadan. The militants, who were still fasting for Ramadan, had attacked the Shias, already celebrating; the Shias claimed to have made their first sighting of the crescent moon, which commences Eid al-Fitr, and the Sunnis did not believe them.[117][118] A contingent of Sunni militants and armed tribesmen from various other places in Pakistan then came to Gilgit, reportedly sent by the Pakistani government to "teach (the Shias) a lesson".[119] Indian intelligence official B. Raman alleged in 2003 that bin Laden had led one of the tribes during the march.[120][121][122]

Formation and structuring of al-Qaeda

By 1988, bin Laden had split from MaK.[123][124] While Azzam acted as support for Afghan fighters, bin Laden wanted a more military role. One of the main points leading to the split and the creation of al-Qaeda was Azzam's insistence that Arab fighters be integrated among the Afghan fighting groups instead of forming a separate fighting force.[124] Notes of a meeting of bin Laden and others on 20 August 1988, indicate that al-Qaeda was a formal group by that time: "Basically an organized Islamic faction, its goal is to lift the word of God, to make his religion victorious." A list of requirements for membership itemized the following: listening ability, good manners, obedience, and making a pledge (bayat) to follow one's superiors.[125]

According to Wright, the group's real name was not used in public pronouncements because its existence was still a closely held secret.[126] His research suggests that al-Qaeda was formed at an 11 August 1988 meeting between several senior leaders of Egyptian Islamic Jihad (EIJ), Azzam, and bin Laden, where it was agreed to join bin Laden's money with the expertise of the EIJ and take up the jihadist cause elsewhere after the Soviets withdrew from Afghanistan.[127] Others argue that the organization was founded earlier and already existed when the leaders met on 11 August.[128][129]

After the Soviets withdrew in February 1989, bin Laden returned to Saudi Arabia, where he was considered as a hero of jihad.[130] Along with his soldiers, he was thought to have brought down the mighty superpower of the Soviet Union.[131] Bin Laden then engaged in opposition movements to the Saudi monarchy while working for the Saudi Binladin Group.[130] He offered to send al-Qaeda to overthrow the Soviet-aligned Yemeni Socialist Party (YSP) government in South Yemen, but was rebuffed by Prince Turki bin Faisal. He then tried to disrupt the Yemeni unification process by assassinating YSP leaders, but was halted by Saudi Interior Minister Prince Nayef bin Abdulaziz after President Ali Abdullah Saleh complained to King Fahd.[132] He was also angered by the internecine tribal fighting among the Afghans.[114] However, he continued working with the Saudi GID and the ISI. In March 1989, bin Laden commanded eight hundred Arab foreign fighters during the unsuccessful Battle of Jalalabad.[133][134][135] He moved his men to immobilize the 7th Sarandoy Regiment, but this led to massive casualties. He funded the 1990 Afghan coup d'état attempt led by radical communist general Shahnawaz Tanai.[135] He also lobbied the Parliament of Pakistan to carry out an unsuccessful motion of no confidence against Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto.[134]

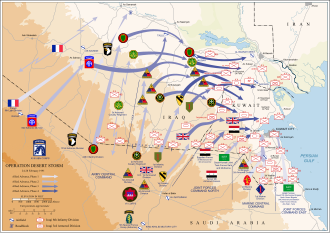

Gulf War

The Iraqi invasion of Kuwait under Saddam Hussein on 2 August 1990, put Saudi Arabia and its royal House of Saud at risk. With Iraqi forces on the Saudi border, Saddam's appeal to pan-Arabism was potentially inciting internal dissent.[136] One week after King Fahd agreed to U.S. Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney's offer of American military assistance, bin Laden met with King Fahd and Saudi Defense Minister Sultan bin Abdulaziz, telling them not to depend on non-Muslim assistance from the U.S. and others and offering to help defend Saudi Arabia with a mujahideen force of his.[136][137] When Sultan asked how bin Laden would defend the fighters if Saddam used Iraqi chemical and biological weapons against them, he replied, "We will fight him with faith."[136] Bin Laden's offer was denied, and the House of Saud invited 500,000 U.S troops to enter Saudi territory.[138][137]

Bin Laden publicly denounced the Saudi deployment.[139] He tried to convince the Saudi ulama to issue a fatwa condemning it, but senior clerics refused out of fear of repression.[140] Bin Laden's continued criticism of the House of Saud led them to put him under house arrest, under which he remained until he was exiled from the country in 1991.[141] After the war, the royals allowed U.S. troops to have a continuous presence there, in Operation Southern Watch, for the purpose of controlling air space in Iraq.[142][143][144] U.S. president George H. W. Bush cited the necessity of dealing with the remnants of Hussein's regime, but decided not to demolish it entirely.[145]

Move to Sudan and first attacks on the U.S.

Meanwhile, on 8 November 1990, the FBI raided the New Jersey home of El Sayyid Nosair, an associate of Ali Mohamed. They discovered copious evidence of terrorist plots, including plans to blow up New York City skyscrapers. This was the earliest discovery of al-Qaeda terrorist plans outside of Muslim countries.[146] It is believed that the first terrorist bombing organized by bin Laden was the 29 December 1992 bombing of the Gold Mohur Hotel in Aden, which killed two people.[130]

In the 1990s, al-Qaeda assisted jihadis financially, and sometimes militarily, in Algeria, Egypt, and Afghanistan. In 1992 or 1993, bin Laden sent an emissary, Qari el-Said, with $40,000 USD to Algeria to aid the local Islamists and urge them to go to war against the Algerian government, rather than negotiate with them. Their advice was heeded. The resulting Algerian Civil War (1992–2002) killed 44,000[147] to 200,000 people, and ended with the Islamists surrendering to the government.[148] In March or April 1992, bin Laden tried to deescalate the civil war in Afghanistan by urging warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar to join other mujahideen leaders in negotiating the creation of a coalition government, instead of Hekmatyar trying to conquer Kabul for himself.[149]

Bin Laden's expulsion from Saudi Arabia came after repeatedly criticizing the Saudi alliance with the U.S.[130][150] He and his followers moved first to Afghanistan, and then relocated to Sudan by 1992,[130][150] in a deal brokered by Ali Mohamed.[151] Bin Laden established a new base for mujahideen operations in Khartoum. He bought a house on Al-Mashtal Street, in the affluent Al-Riyadh neighborhood, and a retreat at Soba on the Blue Nile.[152][153] He personally selected the bodyguards in his security detail, who carried Strela-2s, AK-47s, PK machine guns, rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs), and Stinger missiles.[154] Bin Laden heavily invested in various businesses, like in infrastructure and agriculture.[155] He was popular with local people, who considered him generous to the poor. He built roads in Sudan using the same bulldozers he had employed to construct mountain tracks in Afghanistan, and many of his labourers were former Afghan mujahideen people.[156][157] Bin Laden was also the Sudanese agent for the British aerial photography firm Hunting Surveys.[158] He continued to criticize King Fahd, so in 1994, Fahd stripped him of his Saudi citizenship, and persuaded the bin Laden family to cut off his yearly stipend of $7 million USD.[159][160][161]

In the early 1990s, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed became a top lieutenant of bin Laden, while devising a plan, codenamed "Bojinka", for a series of terrorist attacks by al-Qaeda targeting airliners. In the "Bojinka plot", al-Qaeda and another group, Jemaah Islamiyah, planned for eleven planes departing Southeast Asia towards the U.S. to simultaneously be destroyed by bombs over the Pacific Ocean. Pope John Paul II would also be assassinated.[162][163][164] Mohammed's nephew, Ramzi Yousef, tested out a part of the idea in 1993, when he and a group of men bombed the underground portion of the World Trade Center business complex in New York City, killing six people and injuring more than a thousand.[162][165] In 1994, Yousef rehearsed the Bojinka bombings by setting one off at a theater in Manila, and the other onboard Philippines Airlines Flight 434, which killed a passenger.[166] In 1995, weeks before the planned attack date, the plot was foiled when Yousef's Manila apartment burned down; investigating the fire, police found evidence incriminating him in it.[166][167] Yousef was given life imprisonment in the U.S.,[168] while Mohammed continued working on his idea regarding hijacked airliners.[169]

Around this time, bin Laden had associated more with EIJ, which then made up the core of al-Qaeda. In 1995, the EIJ attempted to assassinate the Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak. The attempt failed, and Sudan expelled the EIJ. After this bombing, al-Qaeda was reported to have developed its justification for the killing of innocent people. According to a fatwa issued by Mamdouh Mahmud Salim, the killing of someone standing near the enemy is justified because any innocent bystander will find a proper reward in death, going to Jannah (paradise) if they were good Muslims, and Jahannam (hell) if they were bad, or non-believers.[170] The fatwa was issued to al-Qaeda members, but not the general public.

The U.S. State Department accused Sudan of being a sponsor of international terrorism, and bin Laden of operating terrorist training camps in the Sudanese desert. However, according to Sudanese officials, this stance became obsolete as Islamist political leader Hassan al-Turabi lost influence in their country. Sudan wanted to engage with the U.S., but American officials refused to meet with them even after they had expelled bin Laden. It was not until 2000 that the State Department authorized U.S. intelligence officials to visit the country.[158]

The 9/11 Commission Report states:

"In late 1995, when Bin Laden was still in Sudan, the State Department and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) learned that Sudanese officials were discussing with the Saudi government the possibility of expelling Bin Laden. CIA paramilitary officer Billy Waugh tracked down Bin Laden in Sudan and prepared an operation to apprehend him, but was denied authorization.[171] US Ambassador Timothy Carney encouraged the Sudanese to pursue this course. The Saudis, however, did not want Bin Laden, giving as their reason their revocation of his citizenship. Sudan's minister of defense, Fatih Erwa, has claimed that Sudan offered to hand Bin Laden over to the United States. The Commission has found no credible evidence that this was so. Ambassador Carney had instructions only to push the Sudanese to expel Bin Laden. Ambassador Carney had no legal basis to ask for more from the Sudanese since, at the time, there was no indictment outstanding against Bin Laden in any country."[172]

In January 1996, the CIA launched a new unit of its Counterterrorism Center (CTC) called the Bin Laden Issue Station, code-named "Alec Station", to track and to carry out operations against his activities. The station was headed by CTC veteran Michael Scheuer.[148] U.S. intelligence monitored bin Laden in Sudan using operatives to run by daily and to photograph activities at his compound, and using an intelligence safe house and signals intelligence to surveil him and to record his moves.[173]

1996 return to Afghanistan

The 9/11 Commission Report states:

"In February 1996, Sudanese officials began approaching officials from the United States and other governments, asking what actions of theirs might ease foreign pressure. In secret meetings with Saudi officials, Sudan offered to expel Bin Laden to Saudi Arabia and asked the Saudis to pardon him. US officials became aware of these secret discussions, certainly by March. Saudi officials apparently wanted Bin Laden expelled from Sudan. They had already revoked his citizenship, however, and would not tolerate his presence in their country. Also Bin Laden may have no longer felt safe in Sudan, where he had already escaped at least one assassination attempt that he believed to have been the work of the Egyptian or Saudi regimes, and paid for by the CIA."

Due to the increasing pressure on Sudan from Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and the U.S., bin Laden was permitted to leave for a country of his choice. He chose to return to Jalalabad, Afghanistan, aboard a chartered flight on 18 May 1996; there he forged a close relationship with Mullah Omar.[174][175] The expulsion from Sudan significantly weakened al-Qaeda.[176] Some African intelligence sources have argued that the expulsion left bin Laden without an option other than becoming a full-time radical, and that most of the three hundred Afghan Arabs who left with him subsequently became terrorists.[158] Various sources report that he lost between $20 million[177] and $300 million[178] in Sudan; the government seized his construction equipment, and he was forced to liquidate his businesses, land, and horses.

In Afghanistan, al-Qaeda raised money from donors bin Laden had associated with during the Soviet–Afghan War—and from the ISI—to establish more training camps for mujahideen fighters.[179] Meanwhile, he effectively took over Ariana Afghan Airlines, which ferried Islamic militants, arms, cash, and opium through the United Arab Emirates and Pakistan, as well as provided false identifications to members of his terrorist network.[180] Russian arms dealer Viktor Bout helped run the airline, maintain planes, and load cargo. Michael Scheuer concluded that Ariana was being used as a terrorist taxi service.[181] In mid-1997, the Northern Alliance threatened to overrun Jalalabad, causing bin Laden to abandon his Najim Jihad compound, and move his operations south to Tarnak Farms.[182]

Declarations of war on the U.S.

In August 1996, bin Laden issued a fatwā titled "Declaration of War against the Americans Occupying the Land of the Two Holy Places", which was published by Al-Quds Al-Arabi, a U.K. newspaper. Saudi Arabia is sometimes called "The Land of the Two Holy Mosques" in reference to Mecca and Medina; "Occupying the Land" referred to Operation Southern Watch.[144] Bin Laden stated: "the 'evils' of the Middle East arose from America's attempt to take over the region and from its support for Israel. Saudi Arabia had been turned into an American colony".[145]

On 23 February 1998, bin Laden issued another fatwā against the U.S., calling upon Muslims to attack the country and its allies. It was entitled "Declaration of the World Islamic Front for Jihad against the Jews and the Crusaders".[183] After listing numerous acts of aggression committed by the U.S., such as the presence of American forces in the Arabian Peninsula, sanctions against Iraq, and the Israeli repression of Palestinians.[184][183] At the fatwa's public announcement, attended by journalists, bin Laden said that North Americans are "very easy targets", and that "you will see the results of this in a very short time."[185] It also claimed the "individual duty for every Muslim "was to liberate [two holy sites] from their grip": Al-Aqsa in Jerusalem and the Masjid al-Haram in Mecca.[186][187]

Late 1990s attacks and criminal charges

Some researchers allege that bin Laden funded the Luxor massacre, the killing of 62 civilians at the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut in Egypt on 17 November 1997.[188][189][190] The Swiss Federal Police later determined that bin Laden had financed the operation.[191]

Another successful attack was carried out in the city of Mazar-i-Sharif, Afghanistan. Bin Laden helped cement his alliance with the Taliban by sending several hundred Afghan Arab fighters to help the Taliban kill 5,000 to 6,000 Hazaras in the city.[192]

On 16 March 1998, Libya issued the first official Interpol arrest warrant against bin Laden. He and three others were charged with killing Silvan Becker, a counterterrorism expert with the German BfV intelligence agency, and his wife Vera in Libya on 10 March 1994.[193][194] Bin Laden was still wanted by the Libyan government at the time of his death.[195][196] He was also indicted by a grand jury in the U.S. on 8 June 1998, on a charges of conspiracy to attack defense utilities of the U.S. and prosecutors further charged that bin Laden was the head of al-Qaeda, and a major financier of Islamic fighters worldwide.[197] Bin Laden and al-Zawahiri organized an al-Qaeda congress on 24 June.[198]

On 7 August 1998, hundreds of people were killed in simultaneous truck bomb explosions at the U.S. embassies in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; and Nairobi, Kenya.[199] The attacks were linked to local members of the EIJ, and brought bin Laden and al-Zawahiri to the attention of the U.S. public for the first time. Al-Qaeda later claimed responsibility for the bombings.[199] Capturing bin Laden became an objective of the U.S.[200] Reception to this initiative among U.S. officials was mixed before 9/11; in 2000, Paul Bremer stated he was in favor of it, while Robert Oakley criticized it.[201] After 9/11, it was revealed that president Bill Clinton had authorized the CIA's Special Activities Division to apprehend bin Laden and bring him to the U.S. to stand trial for the bombings; if taking him alive was deemed impossible, then deadly force could be used.[202] Clinton ordered a series of cruise missile strikes on bin Laden's al-Qaeda training camps in Sudan and Afghanistan on 20 August.[199] They missed bin Laden by a few hours.[203]

On 4 November 1998, bin Laden was indicted by a U.S. federal grand jury in the Southern District Court of New York on charges relating to the embassy attacks. The evidence against him included courtroom testimony by former al-Qaeda members, and records from a satellite phone purchased for bin Laden by al-Qaeda agent Ziyad Khaleel in the U.S.[204][205][206] The Taliban responded to the indictments by saying they would not extradite bin Laden to the U.S., saying there was insufficient evidence present by the court, and that non-Muslim courts lacked standing to try Muslims.[207]

In December 1998, the CIA reported to Clinton that al-Qaeda was preparing attacks in the U.S., including the training of personnel to hijack aircraft.[208] On 7 June 1999, the FBI placed bin Laden on its Ten Most Wanted list.[209] Clinton tried to convince the United Nations (UN) to impose sanctions against Afghanistan in an attempt to force the Taliban to extradite him.[210] He was partially successful, as on 15 October, the UN designated al-Qaeda as a terrorist organization, aiming to freeze assets and impose travel bans on them and their associates.[211] However, the Taliban still did not extradite him.[212]

In late 1999, the CIA and Pakistani military intelligence prepared a team of approximately sixty Pakistani commandos to infiltrate Afghanistan to capture or kill bin Laden, but the plan was aborted upon the Pakistani coup d'état in October.[203] In 2000, foreign operatives working on behalf of the CIA had fired an RPG at a convoy of vehicles in which bin Laden was traveling through the mountains of Afghanistan, hitting one of the vehicles, but not the one he was in.[202]

Involvement in the Yugoslav Wars

Bosnia and Herzegovina

The Bosnian War (1992–1995), an ethnic conflict in the aftermath of the 1991–1992 breakup of Socialist Yugolsavia, saw jihadists in the Bosnian mujahideen, supported by bin Laden, fighting Serb and Croat forces. In 1995, the war ended with the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina's dissolution, and the formation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Following this, many mujahideen veterans formed terrorist groups, which came under the protection of militant elements of the pre-1995 government. Some of these terrorists still had ties to bin Laden as of October 2001.[213][214][215]

Certain ex-mujahideen living north of Sarajevo, the Bosnian capital, around the late 1990s and early 2000s were linked to the same Algerian terrorist cell that once included Karim Said Atmani, a participant in the millennium plots, or to other suspected terrorist groups. Khalil al-Deek was arrested in December 1999 as part of the Jordanian terrorist cell. A second man with Bosnian citizenship, Hamid Aich, lived in Canada at the same time as Atmani, and worked for a charity associated with bin Laden. The New York Times reported in June 1997 that those arrested for the recent bombing of the Al Khobar building in Riyadh confessed to serving with the Bosnian mujahideen. Furthermore, the captured men also admitted to ties with bin Laden.[216][217][verification needed]

In 1999, it was publicized that bin Laden and his Tunisian assistant Mehrez Aodouni had been granted Bosnian citizenship and passports by the previous government in 1993. The new government denied this following the September 11 attacks, but it was later found that Aodouni was arrested in Turkey, and that, at that time, he possessed the Bosnian passport. Following this revelation, a new explanation was given that bin Laden did not personally collect his Bosnian passport, and that officials at the Bosnian embassy in Vienna, which issued it, could not have known who he was at the time.[217][218][verification needed]

Kosovo

The Kosovo War (1998–1999) started over a possible separation of the region of Kosovo—home to many ethnic Albanians—from the Republic of Serbia and Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.[219][220] In 1998, the head of Albania's State Intelligence Service, Fatos Klosi, said that bin Laden had founded a terror network, disguised as a humanitarian organization, in Albania in 1994, and that they were currently taking part in the Kosovo War.[221] Claude Kader, who was a member, later testified to the network's existence during his trial.[221] It was organized by some Islamic leaders in Western Europe allied to bin Laden and al-Zawahiri.[222][218] By 1998, four members of EIJ were arrested in Albania and extradited to Egypt.[223]

In 2002, then-former Serbian and Yugoslav president Slobodan Milošević claimed at his UN trial that he had received an FBI report—which he apparently then read from—that claimed al-Qaeda had aided the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), an ethnic-Albanian paramilitary that had advocated for Kosovo independence, and killed civilians during the Kosovo War. Milošević also claimed that bin Laden had used Albania as a launchpad for violence in the Balkans—as well as that, while Milošević was in office in Yugoslavia (1997–2000), his government had informed U.S. diplomat Richard Holbrooke that the KLA was being aided by al-Qaeda, yet the U.S. decided to continue cooperating with the KLA. Thus, the U.S. was working with bin Laden—despite targeting him after the 1998 embassy bombings—and had created the humanitatrian crisis that the U.S. said had necessitated the 1999 NATO bombing of Yugoslavia.[224][225][226][227]

2000 millennium attack plots

In 1999, al-Qaeda planned multiple terrorist attacks for and around New Year's Day 2000—popularly considered the start of the new millennium—in Jordan, the U.S., Yemen, and India.[228][229][230] The only successful attack was the hijacking of Indian Airlines Flight 814, en route from Kathmandu to Dehli on 24 December 1999. The hijackers, of a connected group to al-Qaeda named Harkat-ul-Mujahideen, kept flying the plane until 31 December, stopping in India, Pakistan, and the UAE along the way. They created a hostage crisis as they kept various passengers on board while making demands from the Indian government. One passenger was killed by the hijackers. The crisis ended when India agreed to let the hijackers be released in Pakistan, and received by the Taliban.[231][232]

Three of the Jordanian targets were symbolic of non-Islamic religions, and were expecting American tourists on New Year's: the Roman Temple of Hercules at the Amman Citadel in Amman; a hill near the Dead Sea where Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist; and Mount Nebo, where Moses climbed to see a view of the Promised Land. Another target was the Radisson hotel in Amman, where many American and Israeli tourists would be. All four attacks were foiled when Jordanian intelligence intercepted a phone call on 30 November from a lieutenant of bin Laden in Pakistan to a member of the terrorist cell in Amman.[228][229]

In the U.S., al-Qaeda planned to bomb Los Angeles International Airport (LAX). It was going to be enacted by a cell in Canada, who would cross the British Columbian border into Washington state before going to Los Angeles. At the border, on 14 December, authorities caught Ahmed Ressam with bomb-making materials in his car.[228][229]

Al-Qaeda also failed in an attempt to bomb USS The Sullivans, a U.S. Navy ship, on 3 January 2000 in Aden, Yemen. The perpetrators had planned to move a boat filled with explosives towards The Sullivans and then detonate them, but they added too many explosives, and the boat sunk before it could reach her. The terrorists then salvaged the boat and the explosives for use in a similar attempt at a later time.[233] They were used in Aden on 12 October, killing 17 Navy sailors aboard USS Cole.[234]

11 September 2001 attacks

On 11 September 2001, 19 al-Qaeda members hijacked four airliners departing the U.S. East Coast in an attempt to crash them into various national landmarks. Two planes, American Airlines Flight 11 and United Airlines Flight 175, were crashed into the Twin Towers in New York City, 1 and 2 World Trade Center (WTC), respectively. American Airlines Flight 77 was crashed into the Pentagon in Virginia. United Airlines Flight 93 did not reach its intended destination, as its passengers overtook the plane, which crashed in a field in Pennsylvania. The Twin Towers eventually collapsed, destroying the World Trade Center.[235][236]

At least 2,977 victims died directly from the four attacks, as well as all of the hijackers.[235][236] An estimated 6,800 people who were near the World Trade Center reported injuries. Numerous people who were at the complex during or after the attacks later received health issues resulting from inhalation exposure caused by dust from the collapse.[237]

U.S. intelligence of 9/11

On the day of the attacks, U.S. and German intelligence intercepted communications that pointed to bin Laden's responsibility in them.[238][239] At 11:30 p.m. EST, U.S. president George W. Bush wrote in his diary: "The Pearl Harbor of the 21st century took place today... We think it's Osama bin Laden."[240] U.S. and U.K. intelligence later stated that classified evidence linking al-Qaeda and bin Laden to 9/11 is clear and irrefutable.[241][242][243] The FBI considers their investigation into 9/11, PENTTBOM, to be their largest criminal investigation ever.[244][245] They conducted 180,000 interviews, reviewed millions of pages of documents, and just within the first few months after the attacks, looked into more than 250,000 leads.[244] Other U.S. federal investigations included Operation Green Quest;[246] the Joint Inquiry into Intelligence Community Activities;[247] and the 9/11 Commission.[248]

July 10, 2001

"The purpose of this communication is to advise the Bureau and [its agents in] New York of the possibility of a coordinated effort by USAMA-BIN-LADEN (UBL) to send students to the United States to attend civil aviation universities and colleges. [The FBI in] Phoenix has observed an inordinate number of individuals of investigative interest who are attending or who have attended civil aviation universities and colleges in the State of Arizona."

In the months before 9/11, U.S. intelligence agenices received numerous warnings about an attack on the U.S. by bin Laden's followers.[249] At the time, many agencies did not significantly cooperate with each other on investigations, so the government did not piece these warnings together to make a cohesive picture of the upcoming attack.[250][251][252] On 10 July 2001, FBI field agent Kenneth Williams wrote the "Phoenix Memo", a warning circulated within the FBI that bin Laden was sending his followers to Arizona for flight training. It was not seen by the agency's leadership until after the attacks.[253] On 6 August, Bush received an intelligence report titled "Bin Laden Determined to Strike in U.S."[254]

Multiple agencies also investigated possible financial ties between Saudi Arabia and bin Laden prior to 9/11.[255][256] Such ties have been alleged by multiple investigators, despite Saudi Arabia having exiled bin Laden in 1991.[257][258] In June 2001, a "high-placed member of a U.S. intelligence agency" told BBC News that after Bush was inaugurated as president that January,[259] his administration forced the agencies to stop looking into any connections.[255]

Militant and political career, 2001–2011

The manhunt for bin Laden and invasion of Afghanistan

The U.S. launched a global "war on terror" in response to 9/11. This included the October 2001 invasion of Afghanistan, to depose the Taliban regime and capture al-Qaeda operatives.[260] This started the War in Afghanistan (2001–2021). Although the Taliban was deposed in December 2001, its members reformed into the Taliban insurgency, which fought the U.S., its allies, and the new Afghan government until the Taliban retook the country in 2021.[261]

The CIA's Special Activities Division was given the lead in tracking down and killing or capturing bin Laden.[262] Bush stated, "I want justice. There is an old poster out west, as I recall, that said, 'Wanted: Dead or Alive'".[263] On 10 October 2001, the FBI introduced a list of its Most Wanted Terrorists, 22 in total, with bin Laden placed atop as the most crucial one to find. The FBI offered a reward of $5 million for information leading to the capture of each person, except bin Laden, who was listed at $25 million.[264][265] In 2007, the Senate voted to double the reward to $50 million, although the amount was never changed.[266] The Airline Pilots Association and the Air Transport Association offered an additional $2 million reward.[267]

Despite these multiple indictments, the Taliban refused to extradite bin Laden. However, they did offer to try him before an Islamic court if evidence of bin Laden's involvement in 9/11 was provided. It was not until eight days after the bombing of Afghanistan began in October 2001 that the Taliban finally did offer to turn over bin Laden to a third-party country for trial, in return for the U.S. ending the bombing. This offer was rejected by Bush, stating that this was no longer negotiable: "there's no need to discuss innocence or guilt. We know he's guilty."[268]

By November 2001, al-Qaeda fighters were still holding out in the mountains around Tora Bora.[269] The CIA, meanwhile, was closely tracking bin Laden's movements in hopes to catch him. On 10 November, they spotted him near Jalalabad traveling in a convoy of two hundred pickup trucks.[270] They then headed towards al-Qaeda's training camp within their defensive complex at Tora Bora, in the Safed Koh mountain range.[270] It was twenty miles from Afghanistan's eastern border with Pakistan.[271] The U.S. attacked it during the Battle of Tora Bora from November to December.[272]

Early in the battle, CIA intelligence had indicated that bin Laden and the al-Qaeda leadership were trapped in the caves of the complex, and on 1 December, CIA officer Gary Berntsen requested General Tommy Franks to send less than a thousand U.S. Army Rangers to block off the mountain passes into Pakistan and cut off bin Laden's escape. However, Franks denied the request, as he agreed with the Bush administration that Pakistan would capture bin Laden if he tried to cross the border.[273][274][275] Bin Laden is conventionally believed to have escaped on 15 December.[276]

Videos and audio recordings

During the invasion of Afghanistan, in November 2001, U.S. forces in Jalalabad reportedly found a videotape in which bin Laden is seen discussing with Khaled al-Harbi what is likely 9/11.[277][278] It was released by the U.S. on 13 December.[278] In it, bin Laden says that it was "calculated in advance [what] the number of casualties from the enemy [would be] based on the position of the towers". He then seems to say that 9/11 exceeded his expectations by the plane impacts unintentionally causing the complete collapse of the towers:[278]

"I was thinking that the fire from the fuel in the plane would melt the iron structure of the building and collapse the area where the plane hit and the floors above it only. That is all we had hoped for."

On 26 December, Al Jazeera broadcast a video message recorded by bin Laden, in which he again seems to imply responsibility for 9/11: "Our terrorism against the United States is worthy of praise to [...]" The tape was probably made around two weeks prior, as he mentions it being three months since a "blessed attack" on the U.S. Many more vague and cryptic audio recordings of bin Laden were released afterwards.[278]

In a 2004 video, he unambiguously confirmed that he had organized 9/11.[95][279] He also threatened new attacks against the U.S., and accused George W. Bush of negligence in not preventing the hijackings.[95][96] The video was first broadcast by Al Jazeera four days before the 2004 U.S. presidential election. Analysts say the timing may have partially led to Bush's win against John Kerry in the election. Supposedly, Americans' fear of terrorism after 9/11 were reintroduced by the video, which, to many voters, may have made Bush seem like a stronger protector of America than Kerry, whose opponents accused him of being weak on terrorism.[95]

After this, al-Qaeda released or distributed videos of bin Laden regularly,[280] some demonstrating his continued survival.[281] One released in 2006 shows him with Ramzi bin al-Shibh, as well as two of the September 11 hijackers, Hamza al-Ghamdi and Wail al-Shehri, as they make preparations for 9/11.[282][283] In a 2007 video, bin Laden denied that the Taliban or the Afghan people had any foreknowledge of 9/11.[284] In 2008, bin Laden threatened to respond to Israeli killings of Palestinians during the 2008–2009 Gaza War with an attack by al-Qaeda. In 2009, he challenged the new U.S. president, Barack Obama, to continue fighting al-Qaeda.[280]

Manhunt, 2002–2005

The CIA opened numerous secret prisons, or black sites, across the world, while the U.S. opened the Guantanamo Bay detention camp in Cuba and the Bagram prison in Afghanistan—all to house confirmed or suspected militants and terrorists.[285][286][287] At those places, the U.S. deployed torture methods, officially named "enhanced interrogation techniques", against prisoners, sometimes in an attempt to get info about al-Qaeda.[288][289][290][291] Research has found torture does not work as an interrogation technique, and often leads to the victims giving false info.[292]

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and bin al-Shibh hid in Pakistan after 9/11.[293] Bin al-Shibh was captured in 2002,[294] then tortured at CIA black sites for four years.[295][296] Mohammed was captured in 2003,[297] then tortured at the sites for three years.[298][297] The CIA unit composed of special operations paramilitary forces dedicated to capturing bin Laden was shut down in late 2005.[299]

Iraq War

Led by the U.S., an international coalition invaded Iraq in 2003 to topple Saddam Hussein's government, starting the Iraq War (2003–2011). In the lead-up to the invasion, the Bush administration tied Hussein to al-Qaeda and 9/11, despite having no evidence internally that Iraq was involved in the attacks.[300][301]

In April 2003, Hussein's government was toppled. Opponents of the invasion then formed the Iraqi insurgency, which fought the coalition and the coalition-installed replacement government.[302] Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the leader of the Sunni insurgent group Jama'at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad (JTJ), declared the group's allegiance to al-Qaeda in 2004, in exchange for bin Laden publicly recognizing him as the head of a new version of JTJ, al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI).[303][304]

AQI became one of the main insurgent forces. Al-Zarqawi intended to use the destabilization caused by the insurgency's war against the coalition to further the sectarian violence between Iraqi Sunnis and Shias, by attacking Shias and their holy sites. He strived for a sectarian civil war that would reestablish the national Sunni dominance over Shias that had been dissolved upon Hussein's ousting.[303][304][305] In February 2006, AQI bombed the al-Askari Mosque in Samarra, Iraq, one of the holiest Shi'ite sites, destroying its upper exterior. The sectarian violence increased as al-Zarqawi intended.[305] He was killed by the U.S. in June, which did not quell the violence.[306]

The vacancy in AQI's leadership led it to become the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI); its allegiance to al-Qaeda continued.[307] ISI decided to capture large swaths of territory in Iraq while fighting the coalition, diminishing support for al-Qaeda among Sunnis who opposed the coalition—even extremist militants.[308][309] The violence between Sunnis and Shi'as only decreased after 2007, as ISI was weakened by greater retaliation from Muslims, and as the U.S. dramatically increased their troop numbers in Iraq in an attempt to stabilize the country.[308][302][304] ISI became independent from al-Qaeda in 2013, when it became the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (IS).[307][310]

Manhunt, 2005–2010

Bush administration

Al-Qaeda member Atiyah Abd al-Rahman sent a letter to al-Zarqawi on 11 December 2005 which indicated that bin Laden and the rest of al-Qaeda's leadership were based in the Waziristan region of Pakistan; Al-Rahman instructed al-Zarqawi to send messengers to Waziristan so that they meet with the other leaders, and indicated that the organization were weak, and experiencing many problems. The letter was found in one of al-Zarqawi's Iraqi safe houses after his death, and was deemed authentic by military and counterterrorism officials.[311][312]

U.S. and Afghan forces again raided the Tora Bora caves in August 2007, after receiving intelligence of a planned meeting between al-Qaeda members for before Ramadan. After killing dozens of al-Qaeda and Taliban members, they did not find either bin Laden or al-Zawahiri.[313]

Obama administration

During Barack Obama's campaign for the 2008 U.S. presidential election, he pledged: "We will kill bin Laden. We will crush al-Qaeda. That has to be our biggest national security priority."[314] Upon being elected, he expressed his plans to renew and ramp up the manhunt.[314] Obama rejected the Bush administration's policy that the manhunt had to consider bin Laden's relation to other militant groups, such as Hamas to Hezbollah, instead narrowing their focus on al-Qaeda and its direct affiliates.[315][316]

In 2009, a UCLA research team led by Thomas Gillespie and John A. Agnew used satellite-aided geographical analysis to pinpoint three compounds in Parachinar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, as bin Laden's likely hideouts.[317] In March 2009, the manhunt had centered in Chitral District of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, including the Kalam Valley, as author Rohan Gunaratna stated that captured al-Qaeda leaders had confirmed that bin Laden was hiding in Chitral.[318] Then-Pakistani prime minister Yusuf Raza Gilani rejected claims that bin Laden was in the country.[319]

Early in December 2009, a Taliban detainee in Pakistan told authorities that bin Laden was in Afghanistan earlier that year. Allegedly, in January or February, the detainee met a trusted contact of his who had seen bin Laden in Afghanistan about fifteen to twenty days earlier.[320] On 6 December 2009, U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates stated that the U.S. had had no reliable information on the whereabouts of bin Laden in years.[320][321] On the 9th, U.S. General Stanley McChrystal said that al-Qaeda would not be defeated unless bin Laden were captured or killed—thus indicating that the U.S. high command believed that he was still alive. Testifying to the U.S. Congress, McChrystal said that bin Laden had become an iconic figure, whose survival emboldened al-Qaeda across the world, and that Obama's deployment of 30,000 extra troops to Afghanistan meant finding bin Laden was possible. He said killing or capturing bin Laden would not dissolve al-Qaeda, but that they definitely could not be dissolved while he remained at large.[321][322]

On 2 February 2010, Afghan president Hamid Karzai arrived in Saudi Arabia for diplomatic talks regarding the Taliban. During the visit, an anonymous official of the Saudi Foreign Affairs Ministry declared that the House of Saud had no intention of getting involved in peacemaking efforts in Afghanistan unless the Taliban severed ties with extremists and expelled bin Laden.[323] On 7 June, the Kuwaiti newspaper Al-Seyassah reported that bin Laden was hiding out in the mountainous town of Sabzevar, in northeastern Iran.[324][325]

In August 2010, as U.S. intelligence was surveilling a man they knew to be a courier of bin Laden, he entered a compound in Abottabad, Pakistan. He continued to frequently the visit the compound, and the U.S. determined that bin Laden was living inside it.[326][327][328] U.S. intelligence later determined that the compound was probably built for him,[329] and may have been his home for at least five years.[330][331] Satellite imagery of the area in 2004 shows no building on the plot.[332] The compound was located less than 2 kilometres (1 mi) from the Pakistan Military Academy, and less than 100 kilometres (62 mi) from Islamabad.[333][334][335]

On 18 October 2010, an unnamed NATO official suggested that bin Laden was alive, well, and living comfortably in Pakistan, protected by elements of the country's intelligence services. A senior Pakistani official denied the allegations, claiming they were made up to put pressure on the Pakistan ahead of talks aimed at strengthening ties between them and the U.S.[336]

2010 European terror plot

In July 2010, a man named Ahmad Sidiqi—who had recently visited a mosque in Germany where some perpetrators of 9/11 had met in the 1990s—was captured in Afghanistan. He was then interrogated by the U.S. at Bagram prison there.[337][338] Notably, American officials tortured Bagram's prisoners during interrogations in the 2000s, and might have still done so by 2012.[339][340] According to the U.S., Sidiqi told them that bin Laden had recently ordered al-Qaeda to conduct terrorist attacks across Europe, which would be similar to the 2008 Mumbai attacks done by Lashkar e-Taiba.[337][341][342] Bin Laden's plot was ultimately foiled by European authorities.[343]

Death and aftermath

On 2 May 2011,[344] Osama bin Laden was shot and killed at his compound in Abottabad, Pakistan, shortly after 1:00 a.m. PKT,[b] in a raid by a U.S. military special operations unit.[345][346][347] The raid, Operation Neptune Spear, was ordered by Obama that April, and carried out in a CIA operation by a team of U.S. Navy SEALs from SEAL Team Six, part of the Joint Special Operations Command. They were supported by CIA operatives on the ground.[333][348][349][350]

The raid was launched from Afghanistan.[351] After the raid, reports at the time stated that U.S. forces had taken bin Laden's body to Afghanistan for positive identification, then buried it at sea, in accordance with Islamic law, within 24 hours of his death.[352] Subsequent reporting has called this account into question—citing, for example, the absence of evidence that there was an imam aboard USS Carl Vinson, where the burial was said to have taken place.[353]

It was widely reported by the press that bin Laden was fatally wounded by Robert J. O'Neill; however, it has also been widely discredited by witnesses, who claim that Bin Laden was possibly already dead by the time O'Neill arrived, having been injured by an anonymous SEAL Team Six member referred to under the pseudonym "Red".[354][355] According to Navy SEAL Matt Bissonnette, bin Laden was struck by two suppressed shots to the side of the head from around ten feet away, after leaning out of his bedroom doorway to survey Bissonnette and a point man. Once the Navy SEALs entered the bedroom, his body began convulsing, and Bissonnette, along with another SEAL, responded by firing multiple shots into his chest.[356]

On 15 June, U.S. federal prosecutors officially dropped all criminal charges against bin Laden.[357] Pakistani authorities demolished the compound in February 2012,[358] to prevent it from becoming a neo-Islamist shrine.[359] In March 2012, a Pakistani intelligence report was released, based on interrogation of bin Laden's three surviving wives, that detailed his movements while hiding in the country.[360]

Allegations of Pakistani support and protection of bin Laden

In 2009, Pakistan said that its intelligence resources were limited, and were thus focused on their war against the Pakistani Taliban and other insurgents, rather than finding bin Laden.[361] After the 2011 raid, the Pakistani ambassador to the U.S., Husain Haqqani, promised a "full inquiry" into how the ISI could have failed to find bin Laden in a fortified compound so close to Islamabad: "Obviously bin Laden did have a support system. [Was] that support system within the government [of] Pakistan, or within the society of Pakistan?"[362] Pakistani columnist Mosharraf Zia wrote at the time: "It seems deeply improbable that bin Laden could have been where he was killed without the knowledge of some parts of the Pakistani state."[363]

For years, the U.S. and Pakistan dually maintained that no Pakistani officials knew of bin Laden's whereabouts prior to, or had prior knowledge of, the raid.[364][365] Journalist Steve Coll wrote in 2018 there was no direct evidence that Pakistan had foreknowledge of bin Laden's location, noting that documents taken from the compound generally show that he was wary of contacting Pakistani intelligence and police about various concerns—especially in light of Pakistan's role in the 2003 arrest of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed.[366]

Journalist Carlotta Gall reported in 2014 that Ahmad Shuja Pasha, while serving as head of the ISI from 2008 to 2012, knew of bin Laden's presence in Abbottabad.[367] Citing U.S. sources, journalist Seymour M. Hersh asserted in 2015 that: bin Laden had been a prisoner of the ISI at the compound since 2006; Pasha knew of Operation Neptune Spear in advance, and authorized the U.S.' helicopters to enter Pakistani airspace; and that the CIA learned of bin Laden's whereabouts from a former agent of Pasha, who was paid an estimated $25 million for the information.[353] Both stories were denied by U.S. and Pakistani officials.

In 2019, Pakistan's prime minister Imran Khan split from his government's prior rhetoric by commenting that the CIA was led to bin Laden by the ISI: "And yet it was [the] ISI that gave the information which led to the location of Osama bin Laden. If you ask [the] CIA, it was [the] ISI which gave the initial location through the phone connection." He did not explain this further.[368] During a 2020 Pakistani parliament session, Khan denounced bin Laden's killing, labelling it as "an embarrassing moment" in their country's history, and also praised bin Laden as a martyr.[369][370][371]

Legacy

After 9/11, numerous countries strengthened their anti-terrorism legislation to deter similar attacks.[260] The U.S. Congress passed the Patriot Act in October 2001, which expanded the powers of U.S. federal agencies to search and surveil criminal suspects; the NSA soon developed a widespread apparatus to surveil U.S. citizens' Internet communications, regardless of if they were suspected for crimes. The extent of the apparatus was only publicized in 2013.[372]

Bin Laden is a reviled figure in the Western world, where he is regarded as a terrorist and mass murderer.[373][374] His The New York Times obituary referred to him as "the North Star" of global terrorism, seen by Americans as equivalent to "Hitler or Stalin."[374] There were large celebrations outside the White House, and in New York City.[375] His killing was also celebrated in India.[376] In Latin America, political leaders expressed opposition to bin Laden upon his death, with Peruvian president Alan García calling him "demonic", while some leftist officials denounced the U.S. for violating Pakistani sovereignty to perform the raid.[377]

Bin Laden's popularity in the Muslim world reached its apex during the Iraq War; opinion polls showed about 50 to 60% of people in certain Muslim countries viewed him favorably.[378][379][380][381] His supporters in those places often displayed photos of him at political demonstrations and speeches.[379] Arab reactions to his death were described as "muted";[382] the Pew Research Center found that bin Laden had become "discredited" in Muslim countries over the preceding years, and support for him had declined steadily. Notably, his favorability rating had reached 1% in Lebanon.[383]

See also

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal 1st General Emir of al-Qaeda Works Killing and legacy |

||

- Allegations of CIA assistance to Osama bin Laden

- List of assassinations by the United States

- Osama bin Laden (elephant)

- Osama bin Laden death conspiracy theories

- Osama bin Laden in popular culture

- The Golden Chain – List of sponsors of Al-Qaeda

Notes

- ^ /oʊˈsɑːmə bɪn ˈlɑːdən/ ⓘ, oh-SAH-mah bihn LAH-dehn.[5] Full name in Arabic: أسامة بن محمد بن عوض بن لادن, romanized: Usāma bin Muḥammad bin ʿAwaḍ bin Lādin, Najdi Arabic pronunciation: [ʔu.saː.ma ben laː.din].

- ^ Depending on the time zone, the date of his death may be different locally.

References

- ^ Fair, C. Christine; Watson, Sarah J. (18 February 2015). Pakistan's Enduring Challenges. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-8122-4690-2. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016.

Osama bin Laden was a hard-core Salafi who openly espoused violence against the United States in order to achieve Salafi goals.

- ^ Brown, Amy Benson; Poremski, Karen M. (18 December 2014). Roads to Reconciliation: Conflict and Dialogue in the Twenty-first Century. Routledge. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-317-46076-3. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016.

- ^ Osama bin Laden (2007) Suzanne J. Murdico

- ^ Armstrong, Karen (11 July 2005). "The label of Catholic terror was never used about the IRA". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016.

- ^ Tedder, Jim (2013). "Voice of America pronunciation of "Osama Bin Laden" from the region of Saudi Arabia". Voice of America. Archived from the original on 2 July 2025. Retrieved 9 June 2025.

- ^ a b "9/11: Why did Osama bin Laden attack the United States?". The Economic Times. 11 September 2025. ISSN 0013-0389. Retrieved 14 February 2026.

- ^ "Fbi – Usama bin Laden". Fbi.gov. 7 August 1998. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ^ a b Engber, Daniel (3 July 2006). "Abu, Ibn, and Bin, Oh My!". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. Retrieved 14 February 2026.

- ^ Davies, William D.; Dubinsky, Stanley (2018). Language Conflict and Language Rights: Ethnolinguistic Perspectives on Human Conflict. Cambridge University Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-107-02209-6.

- ^ "Your questions on the war". 21 November 2001. Retrieved 14 February 2026.

- ^ Zernike, Kate; Kaufman, Michael T. (2 May 2011). "The Most Wanted Face of Terrorism". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 14 February 2026.

- ^ Scheuer 2011, p. 21.

- ^ a b bin Laden, Najwa; bin Laden, Omar; Sasson, Jean (2009). Growing up Bin Laden: Osama's Wife and Son Take Us Inside Their Secret World. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-312-56016-4. Archived from the original on 7 April 2015.

- ^ "Sheikh | Meaning, Title, Significance, & History | Britannica". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 15 July 2025. Retrieved 14 February 2026.

- ^ "Mujahideen | Definition, Meaning, History, & Facts | Britannica". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 11 December 2025. Retrieved 14 February 2026.

- ^ "Emir | Middle East, Rulers, Caliphs | Britannica". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 14 January 2026. Retrieved 14 February 2026.

- ^ "Hajj Pilgrimage Fast Facts". CNN. 21 June 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2026.

- ^ a b ""Obama Osama bin Laden Is Dead"". Columbia Journalism Review. Archived from the original on 14 December 2024. Retrieved 6 February 2026.

- ^ Silverman, Craig (19 December 2011). "The year in media errors and corrections features Osama/Obama, Giffords". Poynter. Archived from the original on 29 January 2025. Retrieved 6 February 2026.

- ^ Reporter, Catherine Bouris (8 February 2025). "CNN Confuses Obama With Osama Bin Laden in Embarrassing On-Air Gaffe". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 7 February 2026. Retrieved 6 February 2026.

- ^ "Usama bin Laden". Rewards for Justice. 29 December 2006. Archived from the original on 29 December 2006.

- ^ "Frontline: Hunting Bin Laden: Who is Bin Laden?: Chronology". PBS. Archived from the original on 10 February 2006. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^ "Osama bin Laden Part 01 of 03". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ "Osama bin Laden Archived 30 July 2025 at the Wayback Machine ", The Economist, 5 May 2011, p. 93.

- ^ a b c Coll, Steve (12 December 2005). "Letter From Jedda: Young Osama- How he learned radicalism, and may have seen America". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 17 January 2010. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^ Scheuer 2011.

- ^ Johnson, David. "Osama bin Laden". infoplease. Archived from the original on 20 January 2008. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^ "Osama bin Laden Fast Facts". CNN. 30 August 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2026.

- ^ "The Mysterious Death of Osama bin Laden". 3 August 2011. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ Beyer, Lisa (24 September 2001). "The Most Wanted Man in the World". Time. Archived from the original on 16 September 2001. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^ Bergen 2006, p. 52

- ^ "Bin Laden's Oxford days". BBC News. 12 October 2001. Archived from the original on 4 September 2017. in, Burke, Jason; Kareem, Shaheen (November 2017). "This article is more than 2 years old Bin Laden's disdain for the west grew in Shakespeare's birthplace, journal shows". The Guardian 1 November 2017 20.50 GMT. Guardian News & Media Limited. Archived from the original on 2 November 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ Messages to the World: The Statements of Osama bin Laden, Verso, 2005, p. xii.

- ^ a b "A Biography of Osama bin Laden". PBS Frontline. Archived from the original on 29 March 2010. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^ Hug, Aziz (19 January 2006). "The Real Osama". The American Prospect. Archived from the original on 30 April 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- ^ Gunaratna, Rohan (2003). Inside Al Qaeda (3rd ed.). Berkley Books. p. 22. ISBN 0-231-12692-1.

- ^ Wright 2006, p. 79.

- ^ Hirst, Michael (24 September 2008). "Analysing Osama's jihadi poetry". BBC News. Archived from the original on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^ "Osama bin Laden's bodyguard: I had orders to kill him if the Americans tried to take him alive". Daily Mirror. 4 May 2011. Archived from the original on 10 June 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ Klausen, Jytte (2021). Western Jihadism: A Thirty Year History (1st ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 44, 45. ISBN 978-0-19-887079-1.

- ^ Encyclopedia of World Biography Supplement, vol. 22, Gale Group, 2002, archived from the original on 18 May 2008

- ^ Slackman, Michael (13 November 2001). "Osama Kin Wait and Worry". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 26 September 2009. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^ Najwa bin Laden, Omar bin Laden, Jean Sasson. Growing Up Bin Laden: Osama's Wife and Son Take Us Inside Their Secret World. p. 414.