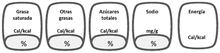

Food labeling in Mexico refers to the official regulations requiring labels on processed foods sold within the country to help consumers make informed purchasing decisions based on nutritional criteria. Approved in 2010 under the Norma Oficial Mexicana (NOM) NOM-051-SCFI/SSA1-2010 (often shortened to NOM-051),[1]: 1 the system includes Daily Dietary Guidelines (Spanish abbrebriation: GDA). These guidelines focus on the total amounts of saturated fats, fats, sodium, sugars, and energy (kilocalories) per package, the percentage they represent per serving, and their contribution to the daily recommended intake.

After its implementation, several studies assessed the effectiveness of the system. The results indicated that most respondents were unaware of the recommended intake levels, struggled to understand the meaning of the values provided by the system, and did not use the system when shopping. Additionally, most undergraduate nutrition students could not interpret the system correctly when questioned.[2] In response, the Secretariat of Health looked for alternatives to the system. In 2016, Chile published a simplified food labeling system, which inspired the creation of a similar system for Mexico.

In 2020, the system was revised and updated with the Food and Beverage Front-of-Package Labeling System (Spanish: {Spanish abbrebriation: SEFAB), developed and implemented by the National Institute of Public Health (INSP).[3] By the end of the year, labeling standards were applied to 85% of food products consumed in Mexico,[4] one of the most obese countries in the world. One year after its implementation, studies found the system had an insignificant impact on sales. However, many companies still adjusted their formulas to reduce risk factor levels.

Development

Background

The influx of foreign food industry capital since the 1980s, coupled with the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994, led to a sharp rise in the import of processed foods into Mexico. These changes triggered an irreversible shift in the country's eating habits and a dramatic increase in obesity rates. In the 1980s, these rates were just 7%.[5] Since then, Mexico has become the leading consumer of processed foods in Latin America and the fourth-largest worldwide, as of 2017.[6]

First front-of-package labeling system

In 2010, the Secretariat of Health (SALUD) requested the establishment of a food labeling norm. After its approval, it was designed as NOM-051-SCFI/SSA1-2010 under the Norma Oficial Mexicana (NOM) standards. The system, called Daily Dietary Guidelines (Spanish: Guías Diarias de Alimentación or GDA), was based on the total amount of saturated fats (grasas saturadas), fats (grasas), sodium (sodio), sugars (azúcares) and energy (calorías) represented in kilocalories per package. It also indicated the percentage these amounts represented per serving and their contribution to daily recommended intake.[7]

The National Institute of Public Health (INSP) began investigating the effectiveness of the labeling system in 2011.[2]: 1 Their findings showed that it was largely ineffective, as most nutrition students were unable to interpret it correctly.[7] In 2016, the National Health and Nutrition Survey (Spanish: Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición) included questions about understanding the GDA food labeling system. The results revealed poor comprehension nationwide. The INSP reported that 97.6% of respondents were unaware of the appropriate calorie intake values for children aged 10 to 12, over 90% did not know the recommended daily calorie intake for adults, and 66.4% never used the GDA system to inform their purchases.[2]: 3 Additionally, a survey conducted by INSP and the University of Waterloo found that only 6% of adults understood the GDA system.[7]

In 2013, the federal government of Mexico launched the 2013 National Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Overweight, Obesity and Diabetes (Spanish: Estrategia Nacional para la Prevención y el Control del Sobrepeso, la Obesidad y la Diabetes),[8] a set of measures by aimed at addressing the obesity crisis and chronic non-communicable diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, and cancer. The strategy highlighted that the current levels of overweight and obesity in Mexico posed a significant threat to the sustainability of the healthcare system, due to their link to non-communicable diseases and the high costs associated with specialized care.[8]: 8 Statistics showed that 42.6% of men over 20 were overweight, and 26.8% were obese. Among women, 35.5% were overweight and 37.5% were obese.[8]: 8 By 2018, 75% of adults were either overweight or obese.[9]

Second front-of-package labeling system

In 2016, the government of Chile enacted the Food Labeling and Advertising Law, which introduced simplified and prominent warning labels to indicate excess calories, added nutrients and additives linked to non-communicable diseases. Inspired by this system, the INSP formed a committee of national academic experts to develop a new regulation for front-of-package labeling of food and non-alcoholic beverages. The Secretariat of Economy (SE) and the Federal Commission for the Protection against Sanitary Risk organized working groups, resulting in a draft standard submitted for public consultation from 11 October to 10 December 2019, gathering 5,200 comments.[10] Simultaneously, civil society organizations, including the Alianza por la Salud Alimentaria (Alliance for Food Health), launched a public campaign to inform the population about these efforts.[9]

On 29 October 2019, reforms and additions to the Mexican General Health Law were approved, including the new front-of-package labeling model. On 27 March 2020, the Official Journal of the Federation published updates to the norm NOM-051-SCFI/SSA1-2010, stipulating that all food and non-alcoholic beverage packaging and containers must display the approved seals.[11]

Labels

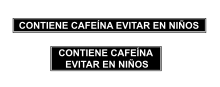

The labels implemented are black octagons with white letters, designed to simply inform consumers about high amounts of sugars, energy, trans fats, and saturated fats. Two rectangular warnings were also added, advising against the consumption of products containing caffeine or sweeteners in children. These labels can appear individually or in groups, which will determine whether the product can include certain persuasive elements, such as toys, rewards, or images of celebrities, fictional characters, or cartoons on the packaging aimed at attracting the attention of minors.[12] Additionally, if the product carries one or more seals, it cannot feature endorsements from medical societies.[13]

| Label | Translation | Application parameters |

|---|---|---|

|

Excessive calories |

|

|

Excessive sugar |

|

|

Excessive sodium |

|

|

Excessive saturated fats | |

|

Excessive trans fats |

|

|

Contains (artificial) sweeteners. Not recommended for children. |

|

|

Contains caffeine. Not recommended for children. |

|

|

1/2/3/4/5 labels |

|

In addition to the seals, packaging must include nutrition facts labels that specify the exact amount of sugars added during the manufacturing process, as well as the nutritional content expressed in quantities of 100 grams or 100 milliliters.[10]

Reception

Companies

The governments of the United States, Canada, Switzerland, and the European Union—where the largest multinational food corporations in the world are based—requested through the World Trade Organization that Mexico postpone the implementation of front labeling. They argued that the measures were "more restrictive than necessary to meet Mexico's legitimate health objectives".[6] The Mexican Consumer Products Industry Council (Consejo Mexicano de la Industria de Productos de Consumo), which represents companies based in Mexico, asked the authorities to eliminate the new front labeling, describing it as confusing and unreliable. Companies such as Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Jugos del Valle and Grupo Bimbo requested the postponement.[15] The latter was able to have some of its products exempted due to its own health strategy.[16] FEMSA, the Coca-Cola producer in Mexico, filed a writ of amparo lawsuit against the labeling of its products.[17] Another amparo lawsuit filed by the National Confederation of Industrial Chambers in March 2020 was dismissed by the Mexican judiciary.[18] The Interamerican Association for the Protection of Intellectual Property and the Mexican Association for the Protection of Intellectual Property stated that food labeling was unconstitutional and violated international agreements Mexico had signed, including the NAFTA.[19] Civil society researchers highlighted the repeated use of this argument in other countries to block new labeling initiatives.[9]

Organizations

Among the organizations and entities that celebrated the implementation of the labeling were UNICEF,[20] the World Health Organization, the Pan American Health Organization,[21] the National Human Rights Commission of Mexico, the country's leading public universities (including the National Autonomous University of Mexico, the National Polytechnic Institute and the Autonomous Metropolitan University), as well as the Mexican Secretariats of Economy and Health and the System for the Integral Protection of the Rights of Children and Adolescents.[10]

Prizes and recognitions

The World Health Organization awarded SALUD for its efforts in the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases due to the front-of-package labeling update.[22][23]

Impact

On population

In a survey conducted shortly after the second front-of-package system was officially implemented, Food Navigator found that only 10% of respondents considered the labels.[24] Researchers from the Obesity Data Lab agreed that the COVID-19 pandemic in the country would likely have indirectly affected the results.[25]

Cuauhtémoc Rivera, president of the National Alliance of Small Merchants (Alianza Nacional de Pequeños Comerciantes), mentioned that consumers initially avoided products with seals, but over time, purchases returned to normal levels.

In 2020, Guadalupe López Rodríguez, nutritionist and researcher of the Autonomous University of the State of Hidalgo, commented that, if the Chilean system were used as a model, the labels would have a significant impact on the population during the initial stage of implementation. However, over time consumers would become accustomed to them and would cease to give them the desired importance.[26] Cuauhtémoc Rivera, president of the Alianza Nacional de Pequeños Comerciantes (National Alliance of Small Merchants), mentioned that consumers initially avoided products with seals, but purchases returned to normal levels subsequently.[27]

After one year of implementation, it was found that consumption had decreased in some categories, but there was no significant impact on sales. Jonás Murillo, vice president of the Food, Beverages, and Tobacco Commission of the Confederation of Industrial Chambers, explained that consumers tended to prefer larger versions of products with labels over smaller, healthier alternatives. Additionally, it was noted that in some cases, consumers favored products with more labels over unlabeled ones. Murillo also pointed out that the key issue with the system was its incorrect application. As an example, he compared a salad with dressing and a bottle of soft drink, concluding that despite their different nutritional values, both products had the same number of labels.[28]

On companies

After its implementation, 85% of the products received a label.[4] Despite inconclusive results, several companies (especially soft drinks and dairy companies) modified the formulas of certain products to reduce the risk levels. In some cases, the total number of labels on products was reduced, while in others, companies opted to sell an alternate version of the same product that was free of labels.[29][30]

See also

Notes

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Rojo Sánchez, Alfonso Guati; Novelo Baeza, José Alonso (27 March 2020). "MODIFICACIÓN a la Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-051-SCFI/SSA1-2010, Especificaciones generales de etiquetado para alimentos y bebidas no alcohólicas preenvasados – Información comercial y sanitaria, publicada el 5 de abril de 2010" [AMENDMENT to Mexican Official Standard NOM-051-SCFI/SSA1-2010, General Labeling Specifications for Prepackaged Foods and Non-Alcoholic Beverages – Commercial and Sanitary Information, published on 5 April 2010] (PDF). Diario Oficial de la Federación (in Spanish). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública (2 May 2019). "Comunicado del Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública de México sobre el amparo indirecto en revisión relacionado con el etiquetado frontal de alimentos" [Press release from the National Institute of Public Health of Mexico regarding the indirect amparo in review related to the front-of-package food labeling] (PDF) (in Spanish). Cuernavaca: El Poder del Consumidor. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Barquera, Simón; et al. (29 May 2018). "Sistema de etiquetado frontal de alimentos y bebidas para México: una estrategia para la toma de decisiones saludables" [A front-of-pack labelling system for food and beverages for Mexico: a strategy] (in Spanish). Salud Pública. Archived from the original on 10 November 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ a b "¿Qué cambia con el nuevo etiquetado de alimentos en México, inspirado en Chile?" [What changes with the new food labeling in Mexico, inspired by Chile?]. El Universal (in Spanish). BBC News. 1 October 2020. Archived from the original on 3 November 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ Jacobs, Andrew; Richtel, Matt (11 December 2017). "El TLCAN y su papel en la obesidad en México" [The NAFTA and its role in obesity in Mexico]. The New York Times (in Spanish). San Cristóbal de las Casas. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ a b Esposito, Anthony (12 August 2020). "Mexico's new warning labels on junk food meet supersized opposition from U.S., EU". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ a b c "Sistema de etiquetado frontal de alimentos y bebidas para México" [Food and Beverage Front-of-Package Labeling System for Mexico]. Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública (in Spanish). Government of Mexico. Archived from the original on 3 November 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Juan López, Mercedes (September 2013). "Estrategia Nacional para la Prevención y el Control del Sobrepeso, la Obesidad y la Diabetes" (PDF) (in Spanish). Government of Mexico. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ a b c White, Mariel; Barquera, Simon (2 June 2020). "Mexico Adopts Food Warning Labels, Why Now?". Health Systems & Reform. 6 (1): e1752063. doi:10.1080/23288604.2020.1752063. ISSN 2328-8604. PMID 32486930. S2CID 219283976.

- ^ a b c "Todo lo que debes saber sobre el nuevo etiquetado de advertencia" [Everything you need to know about the new warning labeling]. El Poder del Consumidor (in Spanish). 12 May 2020. Archived from the original on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ "El nuevo etiquetado de alimentos comenzará a aplicarse el 1 octubre" [The new food labeling system will begin to be implemented on 1 October], Animal Político (in Spanish), 28 March 2020, archived from the original on 15 November 2021, retrieved 15 November 2021

- ^ White, Mariel; Barquera, Simon (1 January 2020). "Mexico Adopts Food Warning Labels, Why Now?". Health Systems & Reform. 6 (1): e1752063. doi:10.1080/23288604.2020.1752063. ISSN 2328-8604. PMID 32486930. S2CID 219283976.

- ^ "Nuevo etiquetado de los alimentos" [New food labeling] (PDF). Dirección General de Personal (in Spanish). National Autonomous University of Mexico. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ "Alimentos con alto contenido de sodio" [Foods with high sodium content] (PDF). PROFECO (in Spanish). Government of Mexico. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ Sánchez, Sheila (28 April 2020). "ConMéxico pide posponer etiquetado frontal para eliminar 'presión' en la industria" [ConMéxico requests to postpone front labeling to eliminate 'pressure' on the industry.]. Forbes (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ "Bimbo se libra de etiquetado de alimentos por contribuir con estrategia de salud" [Bimbo is exempt from food labeling due to its contribution to health strategy]. Reporte Indigo (in Spanish). 30 September 2020. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ "Coca-Cola Femsa promueve amparo contra nuevo etiquetado" [Coca-Cola Femsa files a lawsuit against the new labeling]. Forbes (in Spanish). 28 August 2020. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Rodríguez, Alejandra (6 March 2020). "Revocan a la IP amparo contra norma de etiquetado" [The lawsuit filed by the private sector against the labeling standard is overturned]. El Financiero (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 30 January 2022. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ González, Susana G. (4 December 2019). "Nuevo etiquetado en alimentos y bebidas es anticonstitucional: AIPPI" [New labeling on food and beverages is unconstitutional: AIPPI]. La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Díaz, Ulises (5 February 2020). "UNICEF: El etiquetado frontal de alimentos y bebidas aprobado en México, 'de los mejores del mundo'" [UNICEF: The front labeling of food and beverages approved in Mexico is "one of the best in the world'] (in Spanish). Mexico City: UNICEF. Archived from the original on 22 January 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ "Etiquetado frontal de advertencia, un paso urgente para enfrentar epidemia de sobrepeso y obesidad en México" [Front labeling warning, an urgent step to address the overweight and obesity epidemic in Mexico]. Mexico City: Pan American Health Organization. 30 September 2019. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020.

- ^ "La Secretaría de Salud de México gana premio de las Naciones Unidas por avanzar con el etiquetado frontal de advertencia en alimentos y bebidas" [The Mexican Secretariat of Health wins a United Nations award for advancing with front warning labels on food and beverages.] (in Spanish). Mexico City: United Nations. 24 September 2020. Archived from the original on 23 January 2022. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Montalvo, Alhelí (24 September 2020). "La ONU reconoce a la Secretaría de Salud por nuevo etiquetado frontal de México" [The UN recognizes the Mexican Secretariat of Health for the new front labeling.]. El Economista (in Spanish). Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ "Sin impacto, el nuevo sello" [No impact, the new label]. El Heraldo de México (in Spanish). 6 October 2020. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Rangel, Luz (25 June 2021). "¿Cómo ha impactado en la salud de los mexicanos el nuevo etiquetado frontal de alimentos y bebidas?" [How has the new front labeling of food and beverages impacted the health of Mexicans?]. Reporte Índigo (in Spanish). Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Cadena, Fannia (2020). "Nuevo etiquetado en alimentos y bebidas" [New labeling on food and beverages]. Gaceta UAEH (in Spanish). Autonomous University of Hidalgo State. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ "Etiquetado en alimentos pierde su efectividad" [Food labeling loses its effectiveness]. El Heraldo de México (in Spanish). 11 March 2021. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Saldaña, Ivette; Hernández, Antonio (26 November 2021). "Etiquetado no afecta la venta de comida chatarra" [Labeling does not affect junk food sales]. El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 26 November 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ Gutiérrez, Julio (22 September 2021). "Etiquetado impactó en consumidores; empresas buscan reducir sellos" [Labeling impacted consumers; companies seek to reduce seals]. La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ "Reformulan alimentos chatarra ante etiquetado de advertencia" [Junk food products are reformulated in response to warning labels]. El Heraldo de México (in Spanish). 4 March 2021. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

You must be logged in to post a comment.