The culture of New Mexico is a unique fusion of Native American, Spanish, Mexican and U.S. culture which makes up part of the broader culture of the United States. The confluence of indigenous, Hispanic (Spanish and Mexican), and American influences is also evident in New Mexico's unique cuisine, New Mexican Spanish, New Mexico music, and Pueblo Revival and Territorial styles of architecture. There are more World Heritage Sites in New Mexico than any other U.S. state. New Mexico is one of only seven majority-minority states, with the nation's highest percentage of Hispanic and Latino Americans and the second-highest percentage of Native Americans, after Alaska.[3] The state is home to one-third of the Navajo Nation, 19 federally recognized Pueblo communities, and three federally recognized Apache tribes. Its large Latino population includes Hispanos descended from settlers during the Spanish era, and later groups of Mexican Americans since the 19th century.

New Mexico is an important center of Native American culture. The state bears some of the oldest evidence of human habitation, with thousands of years of indigenous heritage giving way to centuries of successive migration and settlement by Spanish, Mexican, and Anglo-American colonists. The intermingling of these diverse groups is reflected in New Mexico's demographics, toponyms, cuisine, dialect, and identity. Some 200,000 residents, about one-tenth of the population, are of Indigenous descent,[4] ranking third in size,[5] and second proportionally,[6] nationwide. There are 23 federally recognized tribal nations, each with its distinct culture, history, and identity. Both the Navajo and Apache share Athabaskan origin, with the latter living on three federal reservations in the state.[7] The Navajo Nation, which spans over 16 million acres (6.5 million ha), mostly in neighboring Arizona, is the largest reservation in the U.S., with one-third of its members living in New Mexico.[4] Pueblo Indians, who share a similar lifestyle but are culturally and linguistically distinct, live in 19 pueblos scattered throughout the state, which collectively span over 2,000,000 acres (810,000 ha).[8] The Puebloans have a long history of independence and autonomy, which has shaped their identity and culture.[9] Many indigenous New Mexicans have moved to urban areas throughout the state, and some cities such as Gallup are major hubs of Native American culture.[10] New Mexico is also a hub for indigenous communities beyond its borders: the annual Gathering of Nations, which began in 1983, has been described as the largest pow wow in the U.S., drawing hundreds of native tribes from across North America.[11]

Compared to other Western states, New Mexico's Spanish and Mexican heritage remain more visible and enduring, due to it having been the oldest, most populous, and most important province in New Spain's northern periphery.[12] However, some historians allege that this history has been understated or marginalized by persistent American biases and misconceptions towards Spanish colonial history.[13] Almost half of New Mexicans claim Hispanic origin; many are descendants of colonial settlers called Hispanos or Neomexicanos, who settled mostly in the north of the state between the 16th and 18th centuries; by contrast, the majority of Mexican immigrants reside in the south. Some Hispanos claim Jewish ancestry through descendance from conversos or Crypto-Jews among early Spanish colonists.[14] Many New Mexicans speak a unique dialect known as New Mexican Spanish, which was shaped by the region's historical isolation and various cultural influences; New Mexican Spanish lacks certain vocabulary from other Spanish dialects and uses numerous Native American words for local features, as well as anglicized words that express American concepts and modern inventions.[15]

Like other states in the American Southwest, New Mexico bears the legacy of the "Old West" period of American westward expansion, characterized by cattle ranching, cowboys, pioneers, the Santa Fe Trail, and conflicts among and between settlers and Native Americans.[10] The state's vast and diverse geography, sparse population, and abundance of ghost towns have contributed to its enduring frontier image and atmosphere.[10] Many fictional works of the Western genre are set or produced in New Mexico. The state's distinct culture and image are reflected in part by the fact that many Americans do not know it is part of the U.S.;[16] this misconception variably elicits frustration, amusement, or even pride among New Mexicans as evidence of their unique heritage.[17][18]

Architecture

Examples of New Mexico's architectural history date back to the Ancestral Puebloans within Oasisamerica.[citation needed] The Hispanos of New Mexico adapted the Pueblo architecture style within their own buildings, and following the establishment of Albuquerque in 1706, the Territorial Style of architecture blended the styles.[19] Rural communities incorporated both building types into a New Mexico vernacular style, further exemplifying the indigenous roots of New Mexico.[20] After statehood, the modern Pueblo Revival and Territorial Revival architectural styles became more prevalent, with these revival architectures becoming officially encouraged since the 1930s.[21] These styles have been blended with other modern styles, as happened with Pueblo Deco architecture,[22] within modern contemporary New Mexican architecture.[23][24]

Art, literature, and media

The earliest New Mexico artists whose work survives today are the Mimbres Indians, whose black and white pottery could be mistaken for modern art, except for the fact that it was produced before 1130 CE. Many examples of this work can be seen at the Deming Luna Mimbres Museum[25] and at the Western New Mexico University Museum.[26]

Santa Fe has long hosted a thriving artistic community, which has included such prominent figures as Bruce Nauman, Richard Tuttle, John Connell, Steina Vasulka and Ned Bittinger.[27] The capital city has several art museums, including the New Mexico Museum of Art, Museum of Spanish Colonial Art, Museum of International Folk Art, Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, SITE Santa Fe and others. Colonies for artists and writers thrive, and the small city teems with art galleries. In August, the city hosts the annual Santa Fe Indian Market, which is the oldest and largest juried Native American art showcase in the world. Performing arts include the Santa Fe Opera, which presents five operas in repertory each July to August; the Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival held each summer; and the restored Lensic Theater, a principal venue for many kinds of performances. The weekend after Labor Day boasts the burning of Zozobra, a fifty-foot (15 m) marionette, during Fiestas de Santa Fe.

As New Mexico's largest city, Albuquerque hosts many of the state's leading cultural events and institutions, including the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, the National Hispanic Cultural Center, the National Museum of Nuclear Science & History, and the famed annual Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta. The National Hispanic Cultural Center has held hundreds of performing arts events, art showcases, and other events related to Spanish culture in New Mexico and worldwide in the centerpiece Roy E Disney Center for the Performing Arts or in other venues at the 53-acre facility. New Mexico residents and visitors alike can enjoy performing art from around the world at Popejoy Hall on the campus of the University of New Mexico. Popejoy Hall hosts singers, dancers, Broadway shows, other types of acts, and Shakespeare.[28] Albuquerque also has the unique and iconic KiMo Theater built in 1927 in the Pueblo Revival Style architecture. The KiMo presents live theater and concerts as well as movies and simulcast operas.[29] In addition to other general interest theaters, Albuquerque also has the African American Performing Arts Center and Exhibit Hall which showcases achievements by people of African descent[30] and the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center which highlights the cultural heritage of the First Nations people of New Mexico.[31]

New Mexico holds strong to its Spanish heritage. Old Spanish traditions such zarzuelas and flamenco are popular;[32][33] the University of New Mexico is the only institute of higher education in the world with a program dedicated to flamenco.[34] Flamenco dancer and native New Mexican María Benítez founded the Maria Benítez Institute for Spanish Arts "to present programs of the highest quality of the rich artistic heritage of Spain, as expressed through music, dance, visual arts, and other art forms". There is also the annual Festival Flamenco Internacional de Alburquerque, where native Spanish and New Mexican flamenco dancers perform at the University of New Mexico; it is the largest and oldest flamenco event outside of Spain.[35]

In the mid-20th century, there was a thriving Hispano school of literature and scholarship being produced in both English and Spanish. Among the more notable authors were: Angélico Chávez, Nina Otero-Warren, Fabiola Cabeza de Baca, Aurelio Espinosa, Cleofas Jaramillo, Juan Bautista Rael, and Aurora Lucero-White Lea. As well, writer D. H. Lawrence lived near Taos in the 1920s, at the D. H. Lawrence Ranch, where there is a shrine said to contain his ashes.

New Mexico's strong Spanish, Anglo, and Wild West frontier motifs have contributed to a unique body of literature, represented by internationally recognized authors such as Rudolfo Anaya, Tony Hillerman, and Daniel Abraham.[36] Western fiction folk heroes Billy the Kid, Elfego Baca, Geronimo, and Pat Garrett originate in New Mexico.[37] These same Hispanic, indigenous, and frontier histories have given New Mexico a place in the history of country and Western music,[38][39][40] with its own New Mexico music genre,[41][42][43] including the careers of Al Hurricane,[44] Robert Mirabal,[45] and Michael Martin Murphey.[46]

Silver City, originally a mining town, is now a major hub and exhibition center for large numbers of artists, visual and otherwise.[47] Another former mining town turned art haven is Madrid, New Mexico, which was brought to national fame as the filming location for the 2007 movie Wild Hogs.[48] Las Cruces, in southern New Mexico, has a museum system affiliated with the Smithsonian Institution Affiliations Program,[49] and hosts a variety of cultural and artistic opportunities for residents and visitors.[50]

The Western genre immortalized the varied mountainous, riparian, and desert environment into film.[51] Owing to a combination of financial incentives, low cost, and geographic diversity, New Mexico has long been a popular setting or filming location for various films and television series. In addition to Wild Hogs, other movies filmed in New Mexico include Sunshine Cleaning and Vampires. Various seasons of the A&E/Netflix series Longmire were filmed in several New Mexico locations, including Las Vegas, Santa Fe, Eagle Nest, and Red River.[52] The widely acclaimed Breaking Bad franchise was set and filmed in and around Albuquerque, a product of the ongoing success of media in the city in large part helped by Albuquerque Studios, and the presence of production studios like Netflix and NBCUniversal.[53][54][55]

Cuisine

New Mexico is known for its unique and eclectic culinary scene,[56] which fuses various indigenous cuisines with those of Spanish and Mexican Hispanos originating in Nuevo México.[57][58][59] Like other aspects of the state's culture, New Mexican cuisine has been shaped by a variety of influences from throughout its history;[60][57][61] consequently, it is unlike Latin food originating elsewhere in the contiguous United States.[62]: 109 [63][64] Distinguishing characteristics include the use of local spices, herbs, flavors, and vegetables, particularly red and green New Mexico chile peppers,[65][66][67] anise (used in bizcochitos),[68] and piñon (pine nuts).[69]

Among the dishes unique to New Mexico are frybread-style sopapillas, breakfast burritos, enchilada montada (stacked enchiladas), green chile stew, carne seca (a thinly sliced variant of jerky), green chile burgers, posole (a hominy dish), slow-cooked frijoles (beans, typically pinto beans), calabacitas (sautéed zucchini and summer squash), and carne adovada (pork marinated in red chile).[70][71][72] The state is also the epicenter of a burgeoning Native American culinary movement, in which chefs of indigenous descent serve traditional cuisine through food trucks.[73]

New Mexican Spanish

New Mexican Spanish (Spanish: español neomexicano), or New Mexican and Southern Colorado Spanish, refers to the varieties of Spanish spoken in the United States in New Mexico and southern Colorado. It includes an endangered[74] traditional indigenous dialect spoken generally by Oasisamerican peoples and Hispano—descendants, who live mostly in New Mexico, southern Colorado, in Pueblos, Jicarilla, Mescalero, the Navajo Nation, and in other parts of the former regions of Nuevo Mexico and the New Mexico Territory.[75][page needed][76][77][78][page needed][79]

Due to New Mexico's unique political history and over 400 years of relative geographic isolation, New Mexican Spanish is unique within Hispanic America,[74] with the closest similarities found only in certain rural areas of northern Mexico and Texas;[80] it has been described as unlike any form of Spanish in the world.[81] This dialect is sometimes called Traditional New Mexican Spanish, or the Spanish Dialect of the Upper Rio Grande Region, to distinguish it from the relatively more recent Mexican variety spoken in the south of the state and among more recent Spanish-speaking immigrants.[74]

The Spanish language first arrived in present-day New Mexico with Juan de Oñate's colonization expedition in 1598, which brought 600-700 settlers. Almost half the early settlers were from Spain, including many from New Spain, with most of the rest from various parts of Latin America, the Canary Islands, and Portugal. Following the Pueblo Revolt in 1680, New Mexico was resettled again starting in 1692, primarily by refugees from the Pueblo Revolt and others born in northern New Spain. The Spanish-speaking areas with which New Mexico had the greatest contact were Chihuahua and Sonora.[82]

Likely as a result of these historical origins and connections, Traditional New Mexican Spanish shares many morphological features with the rural Spanish of Chihuahua, Sonora, Durango, and other parts of Mexico.[83] Colonial New Mexico was very isolated and had widespread illiteracy, resulting in most New Mexicans of the time having little to no exposure to "standard" Spanish.[84] This linguistic isolation facilitated New Mexican Spanish's preservation of older vocabulary[85] as well as its own innovations.[86]

During that time, contact with the rest of Spanish America was limited because of the Comancheria, and New Mexican Spanish developed closer trading links to the Comanche than to the rest of New Spain. In the meantime, some Spanish colonists co-existed with and intermarried with Puebloan peoples and Navajos, also enemies of the Comanche.[87]

Like most languages, New Mexican Spanish gradually evolved. As a result the Traditional New Mexican Spanish of the 20th and 21st centuries is not identical to the Spanish of the early colonial period. Many of the changes that occurred in older New Mexican Spanish are reflected in writing.[88] For example, New Mexican Spanish speakers born before the Pueblo Revolt were generally not yeístas; that is, they pronounced the ⟨ll⟩ and ⟨y⟩ sounds differently. After the Pueblo Revolt, New Mexico was re-settled with many new settlers coming in from central Mexico, in addition to returning New Mexican colonists. These new settlers generally did merge the two sounds, and dialect leveling resulted in later generations of New Mexicans consistently merging /ʎ/ and /ʝ/.[89] Colonial New Mexican Spanish also adopted some changes which occurred in the rest of the Spanish speaking world, like the elimination of the future subjunctive tense and the second-person forms of address vuestra merced and vuestra señoría;[88] while the standard subjunctive form haya and the nonstandard form haiga of the auxiliary verb haber have always coexisted in New Mexican Spanish, the prevalence of the nonstandard haiga increased significantly over the colonial period.[90]

Before the middle of the 18th century, there is little evidence of the deletion and occasional epenthesis of ⟨y⟩ and ⟨ll⟩ in contact with front vowels, although that is a characteristic of modern New Mexican and northern Mexican Spanish. The presence of such deletion in areas close and historically connected to New Mexico makes it unlikely that New Mexicans independently developed this feature. Although colonial New Mexico had a very low rate of internal migration, trade connections with Chihuahua were strengthening during this time. Many of the people who moved into New Mexico were traders from Chihuahua, who became socially very prominent. They likely introduced the weakening of ⟨y⟩ and ⟨ll⟩ to New Mexico, where it was adapted by the rest of the community.[91]

New Mexico's 1848 annexation by the U.S. led to a greater exposure to English. Nevertheless, the late-19th-century saw the development of print media, which allowed New Mexican Spanish to resist assimilation toward American English for many decades.[92] The 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica, for instance, noted, "About one-tenth of the Spanish-American and Indian population [of New Mexico] habitually use the English language."[93] At the beginning of the 20th century, there was an attempt by both Anglos and Hispanos to link New Mexico's history and language to Spain rather than Mexico. This led to the occasional use of vosotros rather than ustedes in some newspaper ads. Since vosotros isn't actually part of New Mexican Spanish, in these advertisements it was used interchangeably with ustedes, occasionally with both being used in the same ad. That artificial usage differs drastically from the natural usage of vosotros in Spain.[94]

After 1917, Spanish usage in the public sphere began to decline and it was banned in schools, with students often being punished for speaking the language.[95] This punishment was occasionally physical.[96] Newspapers published in Spanish switched to English or went out of business.[97] From then on, Spanish became a language of home and community. The advance of English-language broadcast media accelerated the decline. Since then, New Mexican Spanish has been undergoing a language shift, with Hispanos gradually shifting towards English.[98] In addition, New Mexican Spanish faces pressure from Standard and Mexican Spanish. Younger generations tend to use more Anglicisms and Mexican and standard Spanish forms. The words most characteristic of Traditional New Mexican Spanish, with few exceptions, are less likely to be found in the speech of young people.[99] This is in part due to language attrition. The decline in Spanish exposure in the home creates a vacuum, into which "English and Mexican Spanish flow easily."[100]

In 1983 New Mexican linguist and folklorist Rubén Cobos published the first dictionary of New Mexican Spanish, A Dictionary of New Mexico and Southern Colorado Spanish. Cobos wrote in the introduction that

A dialect of Spanish has been spoken uninterruptedly since the end of the seventeenth century in New Mexico, and since the middle of the nineteenth century in southern Colorado. … Since the early 1940s, with the help of my students at the University of New Mexico and the cooperation of villagers in their sixties, seventies and eighties, I have recorded a large body of New Mexico and southern Colorado Indo-Hispanic folklore materials on magnetic tape. Included in this collection are hundreds of personal interviews and countless examples of corridos and inditas (local ballads), children's games and songs, folktales, chistes (anecdotes), jokes, home remedies, recipes, narratives dealing with local events, proverbs, riddles, songs, versos (rhymed quatrains), and witch stories and accounts of witchcraft. These materials gave me the majority of terms. ...

THE SPANISH SPOKEN in rural areas of New Mexico and southern Colorado can be described as a regional type of language made up of archaic (sixteenth- and seventeenth-century) Spanish; Mexican Indian words, mostly from the Náhuatl; a few indigenous Rio Grande Indian words; words and idiomatic expressions peculiar to the Spanish of Mexico (the so-called mexicanismos); local New Mexico and southern Colorado vocabulary; and countless language items from English which the Spanish-speaking segment of the population has borrowed and adapted for everyday use. New Mexico and southern Colorado Spanish, quite uniform over the whole geographical area, has survived by word of mouth for over four hundred years in a land that until very recent times was almost completely isolated from other Spanish-speaking centers. … offshoot of the Spanish of northern Mexico, especially with respect to usage and pronunciation. ...

in the 1980s, the dialect is losing its struggle for existence because English is the official language of the area (notwithstanding state constitutional articles or amendments to the contrary–especially in New Mexico). The Hispano population in the region lives in an Anglo-oriented environment where all facets of daily living (commerce, education, entertainment, local and national news communications, politics, etc.) use English for their expression. ...

Most young Hispano parents in their twenties and thirties are no longer speaking Spanish to their children. If these young people know Spanish themselves, they find it very difficult and inconvenient to transmit it to their offspring.[80]

Among the distinctive features of New Mexican Spanish are the preservation of archaic forms and vocabulary from colonial-era Spanish (such as haiga instead of haya or Yo seigo, instead of Yo soy);[85] the borrowing of words from Puebloan languages,[101] in addition to the Nahuatl loanwords brought by some colonists (such as chimayó, or "obsidian flake", from Tewa and cíbolo, or buffalo, from Zuni);[102] independent lexical and morphological innovations;[86] and a large proportion of English loanwords, particularly for technology (such as bos, troca, and telefón).[103]

Nowadays the New Mexican Spanish of northern New Mexico, including Albuquerque, is being heavily influenced by Mexican Spanish, incorporating numerous Mexicanisms, while at the same time retaining some archaisms characteristic of traditional New Mexican Spanish. The use of Mexicanisms is most prominent in Albuquerque and Santa Fe, compared to other areas in the north.[96] Some older Spanish speakers have noted Mexican immigrants showing surprise at non-immigrants speaking Spanish. In Albuquerque, the use of Mexicanisms correlates only with age, with younger speakers, regardless of their parents' background, being more likely to use Mexicanisms.[104] Today many native speakers of New Mexican Spanish use the language largely as a sacred language, with many traditional devotions and prayers being in Spanish,[105] and many native speakers are actively using the language with their children.[106] Some experts fear the dialect is threatened with extinction over the next few decades;[74] due to rural flight from the isolated communities that preserved it, the growing influence of Mexican Spanish, and intermarriage and interaction between Hispanos and Mexican immigrants.[96][104] The traditional dialect has increasingly mixed with contemporary varieties, resulting in a new dialect sometimes called Renovador.[80] Today, the language can be heard in a popular folk genre called New Mexico music and preserved in the traditions of New Mexican cuisine.

Sports

No major league professional sports teams are based in New Mexico, but the Albuquerque Isotopes are the Pacific Coast League baseball affiliate of the MLB Colorado Rockies. The state hosts several baseball teams of the Pecos League: the Roswell Invaders, Ruidoso Osos, Santa Fe Fuego and the White Sands Pupfish. The Duke City Gladiators of the Indoor Football League (IFL) plays their home games at Tingley Coliseum in Albuquerque; the city also hosts two soccer teams: New Mexico United, which began playing in the second tier USL Championship in 2019, and the associated New Mexico United U23, which plays in the fourth tier USL League Two.

Collegiate athletics are the center of spectator sports in New Mexico, namely the rivalry between various teams of the University of New Mexico Lobos and the New Mexico State Aggies.[107] The intense competition between the two teams is often referred to as the "Rio Grande Rivalry" or the "Battle of I-25" (in reference to both campuses being located along that highway). NMSU also has a rivalry with the University of Texas at El Paso called "The Battle of I-10". The winner of the NMSU-UTEP football game receives the Silver Spade trophy.

Olympic gold medalist Tom Jager, an advocate of controversial high-altitude training for swimming, has conducted training camps in Albuquerque at 5,312 feet (1,619 m) and Los Alamos at 7,320 feet (2,231 m).[108]

New Mexico is a major hub for various shooting sports, mainly concentrated in the NRA Whittington Center in Raton, which is largest and most comprehensive competitive shooting range and training facility in the U.S.[109]

Historic Sites

Owing to its millennia of habitation and over two centuries of Spanish colonial rule, New Mexico features a significant number of sites with historical and cultural significance. Forty-six locations across the state are listed by the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, the 18th highest of any state.[110]

New Mexico has nine of the country's 84 national monuments, which are sites federally protected by presidential proclamation; this is the second-highest number after Arizona.[111] The monuments include some of the earliest to have been created: El Morro and Gila Cliff Dwellings, proclaimed in 1906 and 1907, respectively; both preserve the state's ancient indigenous heritage.[111]

New Mexico is one of 20 states with a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and among only eight with more than one. Excluding sites shared between states, New Mexico has the most World Heritage Sites in the country, with three exclusively within its territory.[112][113][114]

Humor

Since 1970, New Mexico Magazine has had a standing feature, One of Our 50 Is Missing Archived June 21, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, which relates often humorous anecdotes about instances in which people elsewhere do not realize New Mexico is a state, confuse it with the nation of Mexico, or otherwise mistake it as being a foreign country. The state's license plates say "New Mexico USA", so as to avoid confusion with Mexico, which it borders to the southwest. New Mexico is the only state that specifies "USA" on its license plates.[115]

Notes

References

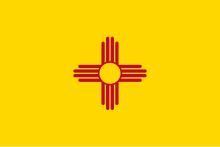

- ^ Kaye, Edward B. (2001). "Good Flag, Bad Flag, and the Great NAVA Flag Survey of 2001". Raven: A Journal of Vexillology. 8: 11–38. doi:10.5840/raven200182. ISSN 1071-0043.

- ^ "New Mexico State Flag – About the New Mexico Flag, its adoption and history from". Netstate.Com. Archived from the original on September 16, 2012. Retrieved June 10, 2012.

- ^ Norris, Tina; Vines, Paula L.; Hoeffel, Elizabeth M. (February 2012). "The American Indian and Alaska Native Population: 2010" (PDF). Census 2010 Brief. United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 5, 2012. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- ^ a b "New Mexico is fourth among states with largest Native American population". Rio Rancho Observer. November 25, 2022. Archived from the original on November 26, 2022. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ^ Rezal, Adriana (November 26, 2021). "Where Most Native Americans Live". Archived from the original on December 28, 2022. Retrieved December 28, 2022.

- ^ "Census.gov". Census.gov. Archived from the original on December 27, 1996. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ Clausing, Jeri. "Fort Sill Apache win land in New Mexico". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on January 19, 2023. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

- ^ "New Mexico". Encyclopædia Britannica. § Climate. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ "The First American Revolution - Archaeology Magazine". www.archaeology.org. Archived from the original on January 19, 2023. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

- ^ a b c "New Mexico". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on October 12, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ "Largest powwow draws Indigenous dancers to New Mexico". The Washington Post.

- ^ Simmons, Marc (1988). New Mexico: An Interpretive History. University of New Mexico Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-8263-1110-8.

- ^ "Apache historian questions official narratives: 'How is it possible that 120 soldiers cut off the feet of 8,000 of our brave Indigenous people?'". MSN. Archived from the original on November 29, 2022. Retrieved November 29, 2022.

- ^ Romero, Simon (October 29, 2005). "Hispanics Uncovering Roots as Inquisition's 'Hidden' Jews" Archived May 14, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times.

- ^ Romero, Simon; Rios, Desiree (April 9, 2023). "New Mexico Is Losing a Form of Spanish Spoken Nowhere Else on Earth". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 10, 2023. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- ^ "Is New Mexico a State? Some Americans Don't Know". NPR. Archived from the original on February 5, 2018. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "Many Americans Can't Quite Place It: New Mexico Finds It's a Lost State". Los Angeles Times. May 31, 1987. Archived from the original on August 18, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "Yes, New Mexico Is a State". www.newmexico.org. June 15, 2018. Archived from the original on August 18, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Shapland, Jenn (November 28, 2018). "The Slash that Killed Santa Fe Style". Southwest Contemporary. Archived from the original on January 11, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ Shacklette, Ben (2012). "Syncretistic Vernacular Architecture Santa Fe, New Mexico". The International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences: Annual Review. 6 (10). Common Ground Research Networks: 157–176. doi:10.18848/1833-1882/cgp/v06i10/52173. ISSN 1833-1882. Archived from the original on April 25, 2023. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- ^ Nelson, Kate (March 24, 2021). "In Mud We Trust". New Mexico Magazine. Archived from the original on January 11, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ Secord, P.R. (2012). Albuquerque Deco and Pueblo. Images of America. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-9526-9. Archived from the original on March 21, 2023. Retrieved March 21, 2023.

- ^ Thompson, H.; Dunn, C. (2021). Santa Fe Modern: Contemporary Design in the High Desert. Monacelli Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-58093-561-6. Archived from the original on March 21, 2023. Retrieved March 21, 2023.

- ^ Keates, Nancy (September 18, 2019). "Thanks to Skiing, It's All Uphill for Santa Fe's Luxury-Home Market". WSJ. Archived from the original on March 21, 2023. Retrieved March 21, 2023.

- ^ "Deming Luna County Museum". Lunacountyhistoricalsociety.com. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 21, 2014.

- ^ "Western New Mexico University Museum". Wnmumuseum.org. Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved April 21, 2014.

- ^ The Santa Fe New Mexican (January 14, 2004), The Santa Fe New Mexican Eldorado, retrieved July 29, 2023

- ^ "Popejoy Hall". Archived from the original on May 16, 2012. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ "KiMo Theater". Archived from the original on May 16, 2012. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ "African American Performing Arts Center, Albuquerque, New Mexico". Aapacnm.org. Archived from the original on April 18, 2012. Retrieved June 10, 2012.

- ^ "Indian Pueblo Cultural Center". Archived from the original on May 13, 2012. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ "Zarzuela in New Mexico". Zarzuela.net. Archived from the original on April 15, 2012. Retrieved June 10, 2012.

- ^ [1] Archived March 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Professor who brought Flamenco to UNM retires". UNM Newsroom. Archived from the original on August 10, 2021. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ Fjeld, Jonathan (June 9, 2023). "Albuquerque to host largest, oldest flamenco event outside of Spain". KOB.com. Archived from the original on June 9, 2023. Retrieved June 9, 2023.

- ^ "New Mexico Authors Page". Archived from the original on August 8, 2012. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ "Billy the Kid, Elfego Baca, Pat Garrett, ca. 1980s – 1990s". New Mexico Archives UNM. December 16, 2022. Archived from the original on November 20, 2023. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ^ "How Clovis Impacted the Growth of Rock & Roll". New Mexico Tourism & Travel. March 18, 2019. Archived from the original on December 16, 2022. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ^ Elizondo, Aleli (November 11, 2022). "International Western Music Association being held in Albuquerque". KRQE NEWS 13 – Breaking News, Albuquerque News, New Mexico News, Weather, and Videos. Archived from the original on December 16, 2022. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ^ Segarra, Curtis (July 8, 2022). "How an Albuquerque nightclub became a library". KRQE NEWS 13 – Breaking News, Albuquerque News, New Mexico News, Weather, and Videos. Archived from the original on December 16, 2022. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ^ "Billy Dawsons Songwriters Country Music Festival". Nashville To New Mexico. June 18, 2022. Archived from the original on December 16, 2022. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ^ Arellano, Gustavo (November 8, 2017). "The 10 Best Songs of New Mexico Music, America's Forgotten Folk Genre". Latino USA. Archived from the original on December 16, 2022. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ^ "NNSA hidden talents: Eric Yee and Lawrence Trujillo make music in New Mexico". Energy.gov. January 8, 2020. Archived from the original on December 16, 2022. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ^ Interns, Our (October 31, 2017). "Viejo el viento – Remembering Al Hurricane". Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. Archived from the original on December 16, 2022. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ^ "Two Taos County musicians named Platinum Music Award honorees". The Taos News. August 14, 2019. Archived from the original on December 16, 2022. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ^ Doland, Gwyneth (July 3, 2018). "Michael Martin Murphey on Why He Loves New Mexico". New Mexico Magazine. Archived from the original on December 16, 2022. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ^ "Silver City Art". Archived from the original on April 21, 2012. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ "Madrid Art". Archived from the original on May 18, 2012. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ "City of Las Cruces". Archived from the original on April 13, 2012. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ "Las Cruces Convention and Visitors Bureau". Archived from the original on June 28, 2012. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ Grabowska, John; Momaday, N. Scott (2006), Remembered earth: New Mexico's high desert, OCLC 70918459

- ^ Christine (January 16, 2012). "A & E will film the new series 'Longmire', starring Katee Sackhoff & Lou Diamond Phillips, in New Mexico this spring". Onlocationvacations.com. Archived from the original on May 11, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2012.

- ^ "Ten Years Later, Albuquerque Is Still Breaking Bad's Town". Vanity Fair. January 17, 2018. Archived from the original on February 20, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- ^ Sisson, Patrick (May 3, 2021). "Albuquerque Is Winning the Streaming Wars". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on April 17, 2023. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ^ Padilla, Anna (June 24, 2021). "NBCUniversal New Mexico production studio to bring hundreds of jobs". KRQE NEWS 13. Archived from the original on December 15, 2022. Retrieved December 15, 2022.

- ^ "Cuisine in Northern New Mexico". Frommer's. Archived from the original on December 28, 2022. Retrieved December 28, 2022.

- ^ a b Casey, C. (2013). New Mexico Cuisine: Recipes from the Land of Enchantment. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-5417-4. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ Swentzell, R.; Perea, P.M. (2016). The Pueblo Food Experience Cookbook: Whole Food of Our Ancestors. Museum of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-89013-619-5. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ Nostrand, R.L. (1996). The Hispano Homeland. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-8061-2889-4. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ Taylor, C. (2016). Moon Route 66 Road Trip. Travel Guide. Avalon Publishing. p. 361. ISBN 978-1-63121-072-3. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ New Mexico Magazine (in Italian). New Mexico Department of Development. 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ Arellano, Gustavo (2013). Taco USA: How Mexican Food Conquered America. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781439148624. Archived from the original on July 15, 2023. Retrieved January 18, 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Laine, Don; Laine, Barbara (2012). Frommer's National Parks of the American West. Wiley. ISBN 9781118224540. Retrieved January 18, 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Sutter, Mike (September 14, 2017). "Review: Need a break from Tex-Mex? Hit the Santa Fe Trail". Mysa. Archived from the original on March 20, 2018. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ "Local Obsession: New Mexican Hatch Chile". Video. April 30, 2022. Archived from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved April 30, 2022.

- ^ Tanis, David (October 14, 2016). "Inside New Mexico's Hatch Green Chile Obsession". Saveur. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved April 30, 2022.

- ^ Larese, Steve (July 1, 2013). "New Mexico Chile: America's best regional food?". USATODAY. Archived from the original on April 30, 2022. Retrieved April 30, 2022.

- ^ Jamison, Cheryl Alters (October 4, 2013). "A Classic Biscochitos Recipe". New Mexico Tourism & Travel. Archived from the original on July 8, 2018. Retrieved July 8, 2018.

- ^ Piñon Nut Act (PDF) (Act). 1978. Retrieved June 25, 2018. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 4, 2021. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "8 quintessential New Mexican foods we wish would go national". Matador Network. May 27, 2011. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ^ "State Symbols". New Mexico Secretary of State. July 3, 2018. Archived from the original on July 7, 2018. Retrieved July 8, 2018.

- ^ "Albuquerque". Bizarre Foods: Delicious Destinations with Andrew Zimmern. Season 3. Episode 15. Archived from the original on November 5, 2020. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ^ "The Native American-owned food trucks taking New Mexico by storm". The Guardian. December 27, 2022. Retrieved December 28, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Romero, Simon; Rios, Desiree (April 9, 2023). "New Mexico Is Losing a Form of Spanish Spoken Nowhere Else on Earth". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 10, 2023. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- ^ Cobos (2003).

- ^ Sando, J.S. (2008). Pueblo Recollections: The Life of Paa Peh. Clear Light Pub. ISBN 978-1-57416-085-7. Retrieved June 2, 2024.

- ^ Iverson, P. (1994). When Indians Became Cowboys: Native Peoples and Cattle Ranching in the American West. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2884-9. Retrieved June 2, 2024.

- ^ Espinosa (1909).

- ^ Espinosa, A.M. (1913). Studies in New Mexican Spanish: Morphology. Sekretariat der "Société internationale de dialectologie romane" Edmund Siemers Allee. Retrieved June 3, 2024.

- ^ a b c Cobos (2003), "Introduction"

- ^ Romero, Simon; Rios, Desiree (April 9, 2023). "New Mexico Is Losing a Form of Spanish Spoken Nowhere Else on Earth". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- ^ Lipski (2008), pp. 193–200.

- ^ Sanz & Villa (2011), p. 425.

- ^ Lipski (2008), pp. 200–202.

- ^ a b Bills & Vigil (2008), pp. 51–74, Ch.5 "Retentions"

- ^ a b Bills & Vigil (2008), pp. 123–151, Ch.8 "El Nuevo México"

- ^ Hämäläinen, Pekka (2008). The Comanche Empire. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12654-9.

- ^ a b Sanz (2009), p. 256.

- ^ Sanz & Villa (2011), pp. 423–424.

- ^ Sanz (2009), p. 219.

- ^ Sanz (2009), pp. 376–381.

- ^ Great Cotton, Eleanor and John M. Sharp. Spanish in the Americas. Georgetown University Press, p. 278.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Gubitosi, Patricia; Lifszyc, Irina (September 2020). "El uso de vosotros como símbolo de identidad en La Bandera Americana, Nuevo México" (PDF). Glosas (in Spanish). 9. ISSN 2327-7181.

- ^ Bills & Vigil (2008), p. 145.

- ^ a b c Waltermire, Mark (2020). "Mexican immigration and the changing face of northern New Mexican Spanish". International Journal of the Linguistic Association of the Southwest. 34: 149–164. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- ^ Gubitosi, Patricia (2010). "El español de Nuevo México y su uso como lengua pública: 1850-1950" (PDF). Camino Real. Estudios de las Hispanidades Norteamericanas. (in Spanish).

- ^ Bills & Vigil (2008), pp. 241–260, Ch.13 "The Long Goodbye"

- ^ Bills & Vigil (2008), pp. 217–218.

- ^ Bills & Vigil (2008), pp. 258–260, 343

- ^ Bills & Vigil (2008), pp. 153–164, Ch.9 "Uneasy Alliances"

- ^ Bills & Vigil (2008), pp. 93–120, Ch.7 "Nahuatlisms"

- ^ Bills & Vigil (2008), pp. 165–190, Ch.10 "Anglicisms"

- ^ a b Waltermire, Mark (2017). "At the dialectal crossroads: The Spanish of Albuquerque, New Mexico". Dialectologia. 19: 177–197. ISSN 2013-2247.

- ^ Dell'orto, Giovanna (May 22, 2023). "New Mexican Spanish, a unique American dialect, survives mostly in prayers". Associated Press. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "A beloved and unique New Mexican Spanish dialect could be fading away". KUNM. April 14, 2023. Retrieved January 18, 2024.

- ^ "New Mexico – The arts". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on October 12, 2023. Retrieved August 11, 2021.

- ^ (10-15-08) "High Hopes: Altitude Training for Swimmers", by Michael Scott, SwimmingWorldMagazine.com Magazine Archives. Archived July 3, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Associated Press (May 2, 2009). "The N.R.A. Whittington Center Shooting Range in New Mexico Caters to All in the Middle of Nowhere". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 13, 2017. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

- ^ "National Register Database and Research – National Register of Historic Places (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on August 28, 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ^ a b Mazurek, Anna (June 18, 2021). "A monumental journey through New Mexico". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 30, 2021. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ^ "Chaco Culture". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on July 27, 2021. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ^ "Taos Pueblo". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on August 14, 2021. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ^ "Carlsbad Caverns National Park". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on August 13, 2021. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ^ Kurtz, Todd (June 21, 2017). "Loving the Land of Enchantment: License Plates". KOAT. Archived from the original on June 27, 2023. Retrieved June 27, 2023.

Sources

- Bills, Garland D.; Vigil, Neddy A. (December 16, 2008). The Spanish Language of New Mexico and Southern Colorado: A Linguistic Atlas. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-4551-6.

- Cobos, Rubén (2003). A Dictionary of New Mexico & Southern Colorado Spanish (2nd ed.). Museum of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-89013-452-9.

- Espinosa, Aurelio Macedonio (1909). Studies in New-Mexican Spanish: Phonology. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- Lipski, John M. (2008). Varieties of Spanish in the United States. Georgetown University Press. ISBN 978-1-58901-651-4. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- Sanz, Israel (2009). The Diachrony of New Mexican Spanish, 1683-1926: Philology, Corpus Linguistics and Dialect Change (PhD). University of California, Berkeley. ProQuest 193999397.

- Sanz, Israel; Villa, Daniel J. (2011). "The Genesis of Traditional New Mexican Spanish: The Emergence of a Unique Dialect in the Americas". Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics. 4 (2): 417–442. doi:10.1515/shll-2011-1107. S2CID 163620325. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

You must be logged in to post a comment.