Batn al-Hawa

Batn al-Hawa | |

|---|---|

| Arabic transcription(s) | |

| • Arabic | حي بطن الهوى |

Interactive map of Batn al-Hawa | |

| State | Palestine |

| Governorate | East Jerusalem |

Batn al-Hawa (Arabic: حي بطن الهوى) is a residential neighborhood inside the village of Silwan, which is located southeast of the Temple Mount/al-Aqsa compound, outside the walls of the Old City of Jerusalem. The neighborhood is located on a mount known in Arabic as Jebel Batn el-Hawa ('Mount of the Belly of the Wind'[1]), which is the southernmost section[1] (or southern extension) of the Mount of Olives ridge east of historical Jerusalem; it is separated from the Mount of Olives proper by the Silwan Valley, which connects to the Kidron Valley at the same point.[failed verification][better source needed][2] The mount is known in Christian tradition as the Mount of Offense or Mount of Corruption.[1]

Location

The Mount of Olives ridge consists of three elevations separated by valleys, with Jebel Batn el-Hawa, 2395 ft. high, being the southernmost.[1]

The hill has been identified in Christian tradition with mons offensioni or scandali, Mount of Offense, by association with the hill from 1 Kings 11:7, set "before" Jerusalem, where the Hebrew Bible says Solomon has erected pagan sanctuaries for his foreign wives.[1] Christian tradition also identifies it with the hill from 2 Kings 23:13, the 'mount of corruption' or 'destruction', although, according to Lucien Gautier writing in 1902, this elevation must be interpreted as the entire Mount of Olives ridge, whereby the sanctuaries' location "on its right hand" can place them either on Jebel Batn el-Hawa, or indeed on Jebel Abu Tor (a hill which Christian tradition identified as the Hill of Evil Counsel).[1]

History

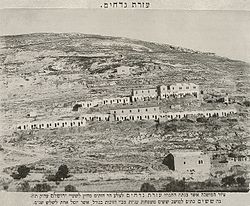

Yemenite-Jewish village (1880s-1930s)

In 1881–82, a group of Jews arrived in Jerusalem coming from Yemen as a result of messianic fervor.[3][4] The year had special meaning to them, for which some thirty Yemenite Jewish families set out from Sana'a for the Holy Land.[5] It was an arduous journey that took them over half a year to reach Jerusalem, where they arrived destitute of all things.[6] Upon reaching Jerusalem, they sought shelter in the caves and grottoes in the hills facing Jerusalem's walls and Wadi Hilweh,[7] while others moved to Jaffa. Initially shunned by the Jews of the Old Yishuv, who did not recognize them as Jews due to their dark complexions, unfamiliar customs, and strange pronunciation of Hebrew, they had to be given shelter by the Christians of the Swedish-American colony, who called them Gadites.[3][4][8] Eventually, to end their reliance on Christian charity, Jewish philanthropists purchased land in the Silwan valley to establish a neighbourhood for them.[9] Between 1885–91, 45 new stone houses were built for the Yemenites[10] at the south end of the Arab village, built for them by a Jewish charity called Ezrat Niddahim.[9] Up to 200 Yemenite Jews lived in the newly built neighbourhood, called Kfar Hashiloach (Hebrew: כפר השילוח, lit.: Siloam Village) or the "Yemenite Village."[11] The neighbourhood included a place of worship now known as the Old Yemenite Synagogue.[9][12] Construction costs were kept low by using the Shiloah spring as a water source instead of digging cisterns. An early 20th-century travel guide writes: In the "village of Silwan, east of Kidron ... some of the fellah dwellings [are] old sepulchers hewn in the rocks. During late years a great extension of the village southward has sprung up, owing to the settlement here of a colony of poor Jews from Yemen, etc. many of whom have built homes on the steep hillside just above and east of Bir Eyyub."[13]

By 1910, the Yemenite Jewish community in Jerusalem and in Silwan purchased on credit a parcel of ground on the Mount of Olives for burying their dead, through the good agencies of Albert Antébi and with the assistance of the philanthropist, Baron Edmond Rothschild. The next year, the community was coerced into buying its adjacent property, by insistence of the mukhtar (headman) of the village Silwan, and which considerably added to their holdings.[14]

Displacement of Palestinians after 1967

After occupying this village in 1967, Israel confiscated more than 73 thousand dunums of its lands for the purpose of establishing settlements there.[15] Settlement began in the town of Silwan with two outposts in the Batn al-Hawa neighborhood in 2004, to which a police station was added to guard, and in 2017 the number increased to thirty Jewish families. The Israeli authorities are planning a massive ethnic displacement operation in the Batn al-Hawa neighborhood, with the aim of judaizing the town of Silwan, where the Israeli authorities intend to issue a decision to displace Palestinian families.[16][17][18][19][20]

18 households (108 people) in the neighborhood are subject of eviction orders issued against them in favor of Ateret Cohanim. The Jewish Benvenisti Trust claim ownership of 5.2 dunums of land, that they say was used to settle Yemenite Jews in the late nineteenth century but who later left Palestine[dubious – discuss] in 1929, during that year's Arab revolt in Mandate Palestine. They premise their claim on a property deed from the Ottoman period. In 2002, the Custodian General transferred the land to the Benvenisti Trust, whose management is now in the hands of Ateret Cohanim. The decision was sanctioned by the Jerusalem District Court. The transfer was done without informing the Palestinian residents who have lived on the land since the 1950s, and who have contracts proving so.[citation needed]

Ateret Cohanim has filed eviction orders against the Palestinian families. The Palestinian residents filed a petition with the Israeli High Court to contest the evictions in 2017 in which they argue that under Ottoman law that applied at the time, the ownership applies only to the buildings, which do not exist anymore, but not to the land itself. In June 2018, the Israeli government acknowledged that the Israeli Custodian General's transfer of the land to the Benvenisti Trust was done without investigating the nature of the Trust, Ottoman laws at the time, or the existing buildings. Yet, the Israeli High Court on November 21, 2018, rejected the appeals of the families, paving the way for the settler group Ateret Cohanim to continue legal proceedings to evict 81 Palestinian families, numbering approximately 436 individuals.[21]

A ruling handed down by the Jerusalem Magistrates Court in January 2020 gave a substantial boost to efforts by the settler organization Ateret Cohanim to evict large numbers of Palestinians in Silwan from their homes. The organization managed to take over control of an Ottoman-era (19th century) Jewish trust, called the Benvenisti Trust after Rabbi Moshe Benvenisti, and claims that land in areas of Silwan, such as the Batan al-Hawa neighborhood, was 'sacred religious land' and that Palestinians residing on this trust land were illegal squatters. The decisions are thought to effectively threaten with displacement some 700 Palestinians in Silwan.[22]

8% of residents are refugees once again at risk of displacement. Since 2015, 14 families have already been evicted. Ateret Cohanim now controls six buildings comprising 27 housing units, the majority of which had been home to Palestinian families.[21]

In June 2021, a plan by Ateret Cohanim to build a heritage center for Yemenite Jewry in the synagogue has been frozen by the Jerusalem Affairs Ministry following an investigation by the religious trusts registry into the Benvenisti Trust in response to a petition by the Ir Amim organization, which alleged that the trust was a shell organization run by Ateret Cohanim for its own purposes and another petition arguing the impropriety of the state financing a heritage center on private property.[23]

On October 25, 2021, the Supreme Court held a hearing on a leave to appeal request by the Duweik family (five households), adjourned with no verdict and will rule in due course.[24] On July 21, 2022, the Court ruled that the case be returned to the Magistrate's Court and the General Custodian be included in the hearing. Therefore the eviction has been prevented for the time being.[25][26]

On January 2, 2026, more than 130 Palestinians in the neighbourhood have faced imminent eviction following a Supreme Court ruling in the largest coordinated displacement wave since 1967, with their appeals being rejected, with evictions beginning as early as January 5. "This is not about individual property disputes or isolated legal cases, but rather a systematic attempt to push Palestinians out of East Jerusalem using discriminatory legislation and mechanisms supported by state institutions," said Emi Cohen, director of international advocacy at Ir Amim.[27]

References

- ^ a b c d e f Gautier, Lucien (1902). "Olives, the Mount of". In Thomas Kelly Cheyne; J. Sutherland Black (eds.). Encyclopaedia Biblica. Vol. III (L-P). Toronto: George N. Morang & Co. Ltd. p. 3496-3499 [3497]. Retrieved October 12, 2025 – via scribd.com.

- ^ "Wadi Hilweh Information Center – Silwan". www.silwanic.net.

- ^ a b Tudor Parfitt (1997). The road to redemption: the Jews of the Yemen, 1900–1950. Brill's series in Jewish Studies, vol 17. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 53.

- ^ a b Nini, Yehuda (1991). The Jews of the Yemen, 1800–1914. Taylor & Francis. pp. 205–207. ISBN 978-3-7186-5041-5.

- ^ Based on a numerological interpretation of the biblical verse "I shall go up on the date palm [tree]" (Song of Songs 7:9), in which the numerical value of the Hebrew words "on the date palm" (Hebrew: בתמר) – 642 – corresponded to the Hebrew year 5642 anno mundi (1881/82), with the millennium being abbreviated, it was expounded to mean, "I shall go up (meaning, make the pilgrimage) in the year 642 of the sixth millennium. Cf. Ramon (1935), p. 5.

- ^ Ramon, Yaakov (1935). Yehudei Teiman Be-Tel Aviv [The Jews of Yemen in Tel-Aviv] (pdf) (in Hebrew). Jerusalem. p. 5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Streetwise: Yemenite steps – Magazine – Jerusalem Post". www.jpost.com. February 28, 2008.

- ^ Messianism, Holiness, Charisma, and Community: The American-Swedish Colony in Jerusalem, 1881–1933, Yaakov Ariel and Ruth Kark, Church History, Vol. 65, No. 4 (Dec., 1996), p. 645

- ^ a b c Man, Nadav (January 9, 2010). "Behind the lens of Hannah and Efraim Degani – part 7". Ynetnews.

- ^ Homepage of the Yemenite Village Synagogue Archived 2021-07-21 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed August 2020.

- ^ Moon, Luke (July 15, 2019). "New York Times Ignores Silwan's Jewish Origins". Providence. Institute on Religion and Democracy. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ Sylva M. Gelber, No Balm in Gilead: A Personal Retrospective of Mandate Days in Palestine, McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP, 1989 p.88

- ^ Cook's Handbook for Palestine and Syria, Thomas Cook Ltd., 1907, p. 105

- ^ Shelomo al-Naddaf (1992). Zekhor Le'Avraham, ed. Uzziel Alnadaf, Jerusalem , pp. 56–57 (in Hebrew).

- ^ "Batan al-Hawa: A Threatened Existence". www.btselem.org.

- ^ "Statement by Manu Pineda on the risk of forced eviction of Palestinians from East Jerusalem | Communiqués | Documents | DPAL | Délégations | Parlement européen". www.europarl.europa.eu.

- ^ "Humanitarian Impact of settlements in palestinian neighbourhoods of East Jerusalem: the coercive environment". United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs – occupied Palestinian territory. July 10, 2018.

- ^ "Subject: Demolition, Evacuation, and Israeli Control of Palestinian Homes and Properties in Occupied Jerusalem". www.palestinepnc.org.

- ^ "Confrontation looms due to continued Israeli land theft". Arab News. March 22, 2021.

- ^ "Three families in Batn Al-Hawa in Silwan are at risk of being evicted and displacing". November 25, 2020 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ a b The Palestinian Human Rights Organisation Council (PHRO) (March 10, 2021). Joint Urgent Appeal to the United Nations Special Procedures on Forced Evictions in East (PDF) (Report).

- ^ 'Settlement Report [The Trump Plan Edition],' Foundation for Middle East Peace January 31, 2020.

- ^ Hasson, Nir. "Project to Open Yemenite Jewish Heritage Center in East Jerusalem Halted" – via Haaretz.

- ^ "Supreme Court Hearing on Duweik Family Eviction Case Adjourns Without a Verdict". us20.campaign-archive.com.

- ^ Ofran, Hagit (July 24, 2022). "The Supreme Court prevented the eviction of the Duweik family from Batan Al-Hawa and returned the hearing to the Magistrate's Court". Peace Now.

- ^ "Israel's Top Court Postpones Eviction of Palestinian Family in East Jerusalem" – via Haaretz.

- ^ العرب, كل (January 2, 2026). "أكثر من 130 فلسطينيًا في القدس الشرقية يواجهون إخلاءً وشيكًا بعد قرار المحكمة العليا - أكبر موجة تهجير منسّقة منذ عام 1967". www.kul-alarab.com (in Arabic). Retrieved January 4, 2026.