República Mista

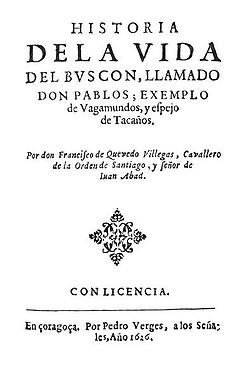

Title page for volume one of República Mista (1602), A Treatise on Three Precepts by Which the Romans Were Better Governed. | |

| Author | Tomás Fernández de Medrano |

|---|---|

| Original title | República Mista: Sobre los Tres Preceptos que el Embajador de los Romanos Dio al Rey Ptolomeo Respecto al Buen Gobierno de su República. |

| Language | Early Modern Spanish and Latin |

| Series | 1 of 7 |

| Subject | Political philosophy, governance, reason of state literature, moral-philosophical discourse, Catholic political theology, Spanish Baroque political literature |

| Genre | Mirrors for princes, political treatise |

| Publisher | Juan Flamenco |

Publication date | 5 March 1602 |

| Publication place | Royal press, Madrid, Spain |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 158 |

República Mista (English: Mixed Republic)[1] is a political treatise of the Spanish Golden Age by Tomás Fernández de Medrano, a Basque-Castilian nobleman, philosopher, royal counselor, and Lord of Valdeosera. Published in Madrid on the royal press in 1602 by decree of King Philip III, it was the first volume of seven treatises Medrano had written, of which only the initial part was published.[2] Composed in early modern Spanish and Latin, the work provides a doctrine of governance grounded in a mixed republic combining monarchy, aristocracy, and timocracy, structured around the foundational precepts of religion, obedience, and justice.[3] Situated within the mirrors for princes tradition, República Mista examines the moral and juridical responsibilities of rulers, magistrates, and subjects, and is noted for its systematic articulation of delegated authority in early modern political thought.[4]

The first treatise of the República Mista significantly influenced early seventeenth-century conceptions of royal authority in Spain, notably shaping Fray Juan de Salazar's 1617 treatise, which adopted Medrano's doctrine to define the Spanish monarchy as guided by virtue and reason, yet bound by divine and natural law.[5]

Without explicitly naming him, it aligns with the anti-Machiavellian tradition by rejecting the view that religion functions only as a political instrument. For Medrano, religion is the foundation of moral order and the precondition for legitimate governance.[6]

Overview and structure

Tomás Fernández de Medrano's codified doctrine, as outlined in the first treatise of República Mista, emphasizes a system of mixed republic explicitly opposed to absolutism, integrating monarchy, aristocracy, and timocracy into a single moral and legal order grounded in religious devotion. He argues that each form of rule embodies particular virtues as well as inherent vices, but when combined within a mixed republic, their strengths serve to limit one another's weaknesses. This mixed model, he maintains, offers the most effective system for securing justice, stability, and the common good.[7]

His República Mista was a written seven-part series, with each volume addressing three key precepts drawn from the seven most flourishing republics in history. Only the first volume was published, devoted to the Roman precepts of religion, obedience, and justice, rooted in ancient philosophy and applied to governance within the Spanish Empire.[3]

The work is structured as a dialogue between King Ptolemy and ambassadors of the classical republics, each presenting three precepts of their polity. In its prologue, Medrano sets out this political doctrine in a style reminiscent of earlier Spanish literature influenced by Arabic traditions, combining narrative with philosophical reflection.[8]

Tomás, who permitted his son Juan to bring the work to publication, explicitly stated he wrote seven treatises, publishing only the first, and included his original intent at the outset of the treatise:

I present only the first of seven treatises I have written, each addressing three points. This one focuses on the primary precepts of religion, obedience, and justice, to see how it is received. If it is well-received, the others will follow, collectively titled Mixed Republic. Since these matters concern everyone, I dedicate this to all, so that each may take what best suits their purpose.[9]

In the first and only printed volume, Tomás Fernández de Medrano illustrates three Roman precepts through scriptural references, historical examples, and contemporary models of leadership. From classical antiquity, he draws on thinkers such as Cicero, Tacitus, Plato, and Aristotle, whose reflections on governance, virtue, and justice underpin much of his analysis.[10]

Exemplary rulers including Lycurgus, Numa Pompilius, and Alexander the Great are invoked as models of wise and ethical leadership, while figures like Codrus and Aristides are cited for their self-sacrifice and devotion to justice.[10] Medrano also praises leaders of his own era, such as Pope Sixtus V, Pope Pius V, and Pope Gregory XIII, for their clemency, piety, and commitment to social order. He incorporates mythological references as well, using Deucalion to symbolize political renewal, Atlas to represent endurance and structure, and Bacchus as an emblem of communal joy and harmony.[11]

Codifying a Universal Doctrine

Although composed in the early seventeenth century, the first volume of the República Mista codified a doctrine of natural precepts already present in earlier traditions across various civilizations. Drawing from classical, biblical, philosophical, legal, and royal sources, Tomás Fernández de Medrano codified these doctrines and natural precepts through the scholastic method, historically upheld in Spanish administrative practice and in the historical vocation of the Medrano family. The treatise united these inherited doctrines and precepts into a coherent system of lawful prosperity (medrar), grounded in virtue, service, delegated authority, and bound by natural and divine law. Together, the family generationally shaped dynastic, legal, educational, and cultural structures across the centuries.[12][13][14]

Authorship

Miguel Herrero García, in his introduction to Fray Juan de Salazar's book, declares:

Don Juan Fernández de Medrano y Sandoval, of the house of the Lords of Valdeosera, is credited as the author of this book, published in Madrid in 1602 under the title República Mista. However, despite what the cover states, we conclude that the book was written by his father, Tomás Fernández de Medrano.[15]

The Spanish bibliographer Nicolás Antonio, knight of Santiago, unequivocally attributes the authorship of the Mixed Republic to Tomás Fernández de Medrano.[16] This father-son collaboration is echoed in the Orazion Consotoria dedicated to Lord Carlo Emanuel, Duke of Savoy, with Tomás as the author and his son Juan responsible for its publication. Similarly, the funeral oration honoring the virtues of King Philip II is also credited to Tomás Fernández de Medrano.[17]

According to the royal printing license issued by Philip III of Spain, Juan Fernández de Medrano y Sandoval discovered "a book titled A Treatise on Three Precepts by Which the Romans Were Better Governed" among the papers of his father, Tomás Fernández de Medrano.[10]

Miguel Herrero García asserts that the royal printing license "leaves no room for doubt" regarding Tomás Fernández de Medrano's authorship. He argues that this was not simply a harmless literary device of the time, citing several points: Medrano was alive when the license was granted, the book contains multiple first-person accounts of events in Italy, it simultaneously functions as a preserver of the oration by Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy, under whom Medrano served as advisor and secretary of state and war (1591—1598).[18]

Author

In his preface, Tomás Fernández de Medrano used a chivalric and theatrical metaphor to explain why he initially wrote República Mista anonymously:

Let no one inquire about the identity of this adventurer, who has dared to step into the public arena with a masked face, fearing the risk of gaining no honor. For that reason, I ask earnestly not to be commanded to reveal myself, for I come from the confines of a prison where I find myself, and I am running this course with these three lances. And if, due to their strength, I cannot break them, I humbly ask the judges to observe where the blows land. I promise they will all strike above the belt, and with such skill that no one will be harmed, offended, or dismounted from their horse. My intentions are truly good.[19]

Born in Entrena, La Rioja, Tomás Fernández de Medrano of the influential House of Medrano held numerous civic, noble, and ecclesiastical titles. He served as Mayor, Chief Magistrate, Divisero, and Lord of Valdeosera, as well as a Knight of the Order of Saint John and Patron of the Convent of San Juan de Acre in Salinas de Añana.[20] Medrano advised the monarchs of Spain and held high office abroad, including Secretary of State and War to Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy, and to Princess Catalina Micaela of Spain, daughter of Philip II.[8]

From 1579 to 1581, he served as secretary to Prince Giovanni Andrea Doria, and later spent eight years in Rome under Enrique de Guzmán, 2nd Count of Olivares.[8] He was appointed Secretary of the Holy Chapters and Assemblies of Castile, maintaining a continued role in both religious and political governance.[20]

Summary by Philip III of Spain

According to the royal decree of King Philip III of Spain in 1601:

Tomás Fernández de Medrano writes first, concerning the importance of kings and princes being religious in order to be more obedient to their subjects; the second, regarding the obedience owed to them by their subjects and the reverence with which they should speak of them and their ministers, councils, and magistrates; and the third, on the Ambassador's role among the Romans, where he discusses why it is important to reward the good and punish the bad.[10]

Historical context

Philip III of Spain (1598–1621), ruler of the Spanish Empire at the height of its power, nevertheless faced challenges in governance.[21][22] In the first volume of the República Mista, titled On the Three Precepts that the Ambassador of the Romans Gave to King Ptolemy Regarding the Good Governance of His Republic, Medrano frames his treatise as a codified doctrine upheld in Spain and focused on the three precepts of religion, obedience, and justice as the foundation of Spanish governance.[10] Philip III's reign established the Pax Hispanica as a doctrinal enactment of these precepts, expressing the unity of religion, obedience, and justice in foreign and domestic governance. Through this, the monarchy was redefined by aligning Roman Catholicism with Hispanidad.[23]

Medrano's doctrinal resolution of early modern ambiguity in mixed government

Early seventeenth-century Spanish political thought combined republican language, scholastic natural law, and classical classifications of government within monarchical frameworks described using republican and mixed constitutional language.[24] As analyzed by Rubiés, this convergence produced persistent uncertainty over how unified royal authority related to plural structures of governance, including councils, magistracies, and representative institutions, in the absence of a settled account of their relation to sovereign power.[24] The República Mista (1602) of Tomás Fernández de Medrano provides a doctrinal resolution of this problem. Medrano defines the Spanish polity as a mixed Republic ordered to the common good and governed through sound doctrines and natural precepts, treating monarchy, aristocracy, and timocracy as enduring forms of governance operating within a single moral and legal order.[4]

Sovereign authority is unified in the prince, while the exercise of government proceeds through councils, offices, and virtuous magistrates selected according to service, merit, and equity.[25] These institutions regulate the use of power, preserve justice, and maintain political stability without fragmenting sovereignty. The República Mista codified doctrine and precepts already upheld in Spanish governance, transmitted through the reign of Philip II and confirmed in law under Philip III. In the 1595 preamble to the Ordenações Filipinas, Philip II defines kingship as the administration of justice for the preservation of peace within the Republic.[26]

The Doctrine of Medrano ensured the sacred and judicial legacy of the Spanish Monarchy was preserved and passed on as the definitive model for the largest empire on the planet. While the Ordenações Filipinas provided binding legal precepts of justice, merit, and equity within the Portuguese realm, the República Mista extended these precepts into a comprehensive mixed republic, applicable to the Spanish Monarchy as a whole, clarifying the relationship between unified sovereignty and plural forms of governance.[4]

The eight royal regalia in the Spanish Empire

In the early 17th century, a strong royalist ethos emerged, asserting that the king was legibus solutus (not bound by laws) in civil matters, though still subject to divine and natural law. Phrases like scientia certa, motu proprio, and non obstante facilitated the development of royal sovereignty, which was nevertheless distinguished from tyranny.[27][28] This interpretation of royal power was so widely accepted that República Mista (1602) by Tomás Fernández de Medrano codified and reaffirmed the king's authority in civil affairs and taught that resistance to a legitimate ruler was contrary to divine and natural law, citing scriptural foundations from 1 Samuel 8 to Jeremiah 27.[28]

Tomás teaches that free rulers possess the authority to make and enforce laws upon all, both generally and individually. This authority contains the symbols and acts of supreme sovereignty that jurists call the Regalia. He states that the Regalia may be distilled into eight primary points, so that their lawful exercise may be better understood and obeyed:

- Eight Primary Points of Regalia: To create and repeal laws. To declare war or establish peace. To act as the highest court of appeal. To appoint and remove high officials. To levy and collect taxes and public contributions. To grant pardons and dispensations. To set or alter the value and currency of money. To require oaths of loyalty and obedience from all subjects.

If rulers exercise these powers, either directly or through ministers to whom authority is delegated, subjects must not scorn or violate the authority of their superiors. Established by God through many decrees and testimonies, this authority must be respected and held as a source of majesty, even if at times it is administered by individuals who are unworthy and make it odious. Subjects must obey laws and ordinances without scheming or undertaking anything that undermines the dignity and authority of princes, ministers, and magistrates.

The two forms of authority and justice in the Spanish Empire

Tomás Fernández de Medrano asserted there are two types of authority:

- (1) One supreme and absolute, answerable only to God (fundamentally opposed to absolutism).

- (2) Subordinate and bound by law, exercised by magistrates for a limited time under royal commission (e.g. a valido).[3]

Tomás taught that any discussion of royal authority must begin with the classical distinction between the two forms of justice. He explained that philosophers divide justice into distributive and commutative, and that the first is most relevant for kingship.

- (1) Distributive justice concerns the rightful granting of honor, dignity, office, punishment, and reward according to each person's condition.

- (2) Commutative justice concerns the fair observance of promises, contracts, and reciprocal duty.

He cited the universal maxim:

Quod tibi non vis, alteri ne feceris "Do not do unto others what you would not wish done unto you."[7]

Medrano emphasized that all justice is ordered toward the preservation of human society. It is the guardian of the laws, the defender of the good, the enemy of the wicked, and indispensable to all estates. Even pirates and highway robbers, he noted with Cicero, cannot exist without some form of internal justice among themselves. This demonstrates that justice is not only a virtue but a structural condition of any society, lawful or unlawful.

To characterize its supreme importance, Medrano invoked the Pythagorean Paul, who taught that justice is the mother from whose breast all other virtues are nourished. Without justice, he explained, no one could be temperate, moderate, courageous, or wise. In this sense, justice is not merely one virtue among many, but the foundation upon which the moral order rests and through which every other virtue becomes possible.

Tomás added that the perfection of justice requires an even higher standard. Drawing from Plato, he taught that true justice cannot distinguish among men on the basis of friendship, kinship, wealth, or dignity. It demands that rulers set aside personal pleasures and private benefits in order to embrace the common good, even at their own cost.

He explained that good governance requires the prohibition of anything doubtful, because uncertainty itself signals danger.

Equity is by nature so clear and resplendent that where doubt exists, injustice is near.[7]

By this, Medrano affirmed that just rulers must banish ambiguity from public affairs. Justice provides the vigilant preservation of clarity, equity (aequitas) and the public good.

Medrano's Contemporary Defense of Philip III of Spain

While many modern historians regard Philip III of Spain as a weak and disengaged monarch,[29] Medrano presents a humble description in República Mista (1602):

Is there a greater example of justice and sanctity than the one shown by our Lord King Philip III in Valladolid? When constructing a passage for his own comfort and convenience, he graciously sent a request to a poor baker, asking him, with utmost respect, if he would allow the passage to go through a small room in his house. The baker, responding with loyalty and wisdom beyond his station, answered that the King's will should be done, as his life and livelihood were at the King's disposal. In return, the King rewarded this common man with generous gifts befitting a humble subject who had served his King like a true noble.

Anecdotes, such as the king requesting permission from a baker to pass through his home, illustrate Medrano's view of Philip III grounded in fairness and magnanimity.

Tomás Fernández de Medrano teaches that discretion and restraint are necessary virtues for subjects who live under a just Catholic king. He writes:

Interdum "Sometimes it is convenient not to know certain things."

He then cites Seneca:

Qui plus scire velle quam satis sit; intemperantiae genus est "Wanting to know more than is necessary is a form of excess."

Such restraint strengthens loyalty to the king, to his councils, and to his magistrates. It helps preserve a measure of peace in this life and reminds humanity that this world is not their lasting home. Therefore, the loyalty and silence of subjects toward their king and rightful lord, and toward his councils and magistrates, are crucial virtues within the populace and powerful means of attaining some peace in this life. He teaches that this peace reminds us "that we live and journey toward an eternal life, not this fleeting, mortal, and transitory one."

All great monarchies eventually fall. Nothing beneath heaven is immortal. Tomás therefore asks:

qui potest dicere immortalitatem sub coelo "Who can claim immortality under heaven?"

Subjects are instructed to pray that God preserve their holy, valiant, magnanimous, generous, just, wise, and compassionate king.

Tomás then describes Philip III's virtues. The king is holy because he has no disordered inclinations and entrusts difficult matters to wise and religious counselors placed beside him by divine providence. He is valiant because he understands that power collapses unless it is accompanied by real strength. For this reason he assembled a great fleet and army that humbled his greatest enemies without requiring bloodshed or his personal presence on the battlefield.

He is magnanimous because he could have annihilated certain princes for his advantage yet chose to show them mercy. Tomás cites Saint Isidore:

Plerunque princeps iustus etiam malorum errores dissimulare novit, non quod iniquitati eorum consentiat; sed quod aptum tempus correctionis expectet "A just prince often knows how to overlook even the errors of the wicked, not because he approves of their iniquity but because he waits for the appropriate time to correct them."

Medrano affirms that Philip III is just because he knows the gravity of governing well and has personally visited his realm, listening to and correcting the needs of his subjects.

Tomás then repeats the ancient warning that an emperor who encloses himself at home and sees only what others report will judge poorly. He quotes Diocletian:

Bonus, cautus, optimus venditur Imperator "The good, the prudent, and the excellent emperor is a rare treasure."

The king is prudent because although naturally inclined to hunting and war, he has set these aside for noble and sacred reasons, serving God, preserving his health, and benefiting his people. A ruler's moderation, he writes, reforms customs.

He is compassionate because, at the urging of Pope Clement VIII, whom he deeply venerates, he acted against the harsh maxim of Sallust:

Nemo alteri imperium volens concedit; et quamvis bonus, atque clemens sit, qui plus potest, tamen quia malo esse licet formidatur "No one willingly yields power to another; and even though he may be good and gentle, one who holds power is feared because he has the capacity to be otherwise."

Though kings generally believe that yielding is as shameful as defeat, Philip III yielded when justice and charity required it, choosing to safeguard the peace the monarchy enjoys. Tomás cites Saint Gregory:

Reges quando boni sunt, muneris est Dei; quando vero iniqui, sceleris est populi "Good kings are the gift of God, and wicked ones are the punishment of the people."

He concludes with a reflection on human nature. Those inclined to speak freely and condemn injustice often displease the powerful. Tomás recalls Tacitus:

Semper alicui potentium invisus, non culpa, sed ut flagitiorum impatiens "One who is always disliked by the powerful is not guilty of wrongdoing but rather intolerant of wrongdoing."

For this reason he advises that those who seek peace and security will often prefer to live far from courts and the pressures of public life, where they may enjoy a more tranquil existence.

In his República Mista, Tomás Fernández de Medrano presents Philip III as the model of a virtuous Catholic monarch, demonstrating that holy kingship is upheld not through force alone but through justice, prudence, mercy, and piety.

Medrano's Doctrine of Royal Sovereignty and its Impact

In 1617, Medrano's codified doctrine in the República Mista was fully embraced by Fray Juan de Salazar in his attempt to define the Spanish monarchy.[30][31] In the República Mista, Medrano further advised King Philip III that royal withdrawal from public view could be perceived "as a form of religion," comparing the king's distance from his subjects to the veneration reserved for the Eucharist.[32][33] In response to this vision, Philip III took the idea of royal inaccessibility even further than his father, restricting public access and delegating the management of audiences to the Duke of Lerma, reinforcing the king's sacred distance with the second type of authority.[34][35] He balances sacred distance by arguing that what is rarely seen is more deeply revered, and that this deliberate isolation preserved the king's idealized image by concealing potential flaws, thereby legitimizing the presence of a valido to act as his public and political representative.[36][37]

Medrano's Classical Model of Sacred Royal Reserve

After affirming that reverence for God restrains the violent impulses of power and that princes must protect the sanctity of the Church above all, Medrano shifted to the classical figure who embodied these precepts most fully. Tomás Fernández de Medrano turned to the classical figure of Numa Pompilius to define the proper form of sacred kingship. Following the violent era of Romulus, Numa governed by moderation, peace, and religious example. Medrano used this contrast to show that a kingdom shaped by war and ambition can only be stabilized by a ruler whose virtues restrain the impulses of the people. Numa, in Medrano's account, performed the duties of government and then withdrew to contemplation of divine matters, cultivating a kingdom whose religious discipline made even foreign nations regard Rome as inviolable.

At the center of Medrano's political theology was the principle that the king exists so that his subjects may prosper (medrar). He expressed this using the foundational maxim of the doctrine:

Rex eligitur non ut sese moliter curet, sed ut per ipsum, qui elegerunt, bene beateque agant. A king is chosen not to care for himself but so that, through him, those who chose him may live well and prosper.

For Medrano, royal majesty depends on measured distance. The sovereign must avoid excessive familiarity and be known primarily through counselors whose own conduct inspires confidence. Drawing on the example of Tiberius, he wrote:

Continuus aspectus venerationem minorum hominum ipsa societate facit. Continual familiarity diminishes the reverence held for men by simple association.

From these teachings Medrano concluded that a king's dignity grows from his rare public presence and from the elevation of a trusted minister who serves as the visible executor of royal will. Philip III's restricted audiences, his disciplined reserve, and his reliance on the Duke of Lerma were therefore not signs of indolence or weakness. They were enactments of a sacral form of government in which distance magnified majesty and delegated authority allowed the people to live well and prosper, fulfilling the doctrinal standard Medrano had inherited and codified.

Reception and International Influence

In a letter dated around 1607, Tomás Fernández de Medrano reported that Philip III and his ministers were well aware of the services he had rendered by sea and land, in peace and war, and of his political treatise concerning the governance of the Republic.[38]

His Majesty was pleased by the book he wrote on the Republic (dedicated to the Duke of Lerma), in which he discussed, among other things, how important it is for kings and princes to be religious in order to be better obeyed by their subjects.[38]

Medrano's República Mista significantly shaped Philip III's approach to kingship.[39][40][37] His República Mista reinforced Madrid-Rome ties,[41] and associated a religious foundation with the Spanish monarchy's "greatness" and prestige.[42]

Medrano's Contemporary Defense of the Valido of Spain

Tomás Fernández de Medrano's vision of kingship, rooted in sacred distance, obedience, and divine legitimacy, naturally called for a trusted intermediary to manage public affairs. In this context, the figure of the valido emerged not as a rival to the monarch, but as a functional extension of his will: a visible minister acting on behalf of an invisible king.[43]

With the accession of Philip III in 1598, political literature increasingly turned its attention to the role of the valido. In República Mista (1602), Tomás Fernández de Medrano defined and defended the value and legitimacy of the valido through historical examples.[44] Drawing on lesser-known figures such as Callisthenes, adviser to Alexander the Great, and Panaetius of Rhodes, companion to Scipio Aemilianus, Medrano argued that trusted confidants could serve not as threats to royal authority but as prudent and loyal counselors who strengthened effective governance.[45]

He observes the value of such counsel:

We see that there has not been a great and prudent prince who did not have a servant as a faithful friend, someone (to discreetly moderate his passions, help him carry the burden, and speak the truth) with more authority than all others. Callisthenes served this role for Alexander, Panaetius for Scipio, and many other secretaries whose experience and prudence have brought much glory to the governance of many princes. These princes, if they are wise and experienced, shape their ministers to fit their needs. And conversely, expert ministers make prudent and glorious the princes who are not, if those princes are teachable. Happy, then, in my view, is the one who says this, and happy the republic when such a servant, friend, or valido proves to be of such a nature that the deeds of his heart and courage correspond in greatness to the one whom kings and princes ought to have. For where there is nobility of blood, and noble habits and customs, there can be nothing that does not reflect it. And so, what shall we say when to all this is added such zeal, goodness, and piety as we now see, witness, and experience?[46]

Amid growing criticism of the valido (royal favourite) during the early reign of Philip III, Tomás Fernández de Medrano offered a contrasting perspective in República Mista (1602). While many contemporary thinkers viewed the concentration of royal trust in a single individual as a threat to authority, Medrano, writing under the patronage of the Duke of Lerma, defended the political utility of the valido.

He presented the figure of the valido not as a rival to the king, but as a necessary extension of royal governance, someone entrusted with distinct responsibilities that contributed to a more unified and effective administration.[47] While defining delegated authority, Medrano simultaneously denounces favoritism and the corruption of courtly life. He strongly criticizes nepotism, flattery, and the promotion of the unworthy, urging sovereigns to honor merit and uphold justice as a foundational precept of their authority.[48]

This vision of a prudent valido did not end with Tomás Fernández de Medrano, Lord of Valdeosera. His great-nephew, Diego Fernández de Medrano y Zenizeros, Lord of Valdeosera and Sojuela; a nobleman, a presbyter, and chaplain to Luis Méndez de Haro, Valido of Philip IV, carried the doctrine forward in a later panegyric-treatise titled Heroic and Flying Fame.[49] He invoked figures such as Aristotle, Euclid, Apelles, and Lysippus to frame Haro's statesmanship as surpassing the achievements of antiquity. Where Tomás drew on classical examples to justify the role of the valido, Diego used them to exalt Haro as its most refined expression. His work immortalizes Luis de Haro, nephew and successor of the Count-Duke of Olivares, as an exemplary valido whose conduct embodied wisdom, restraint, and virtue, notably during his negotiations at the treaty of the Pyrenees.[49]

Dedication to the Duke of Lerma

Tomás Fernández de Medrano's son presented a spirited defense of the system of the valido that emerged with the rise of Philip III.[5] The República Mista is openly dedicated to Francisco de Sandoval y Rojas, 1st Duke of Lerma, the first great valido, as its patron, dated 22 August 1601.[6]

Medrano's son, Juan Fernández de Medrano y Sandoval, addresses the Duke as follows:

The ship governed by two captains is endangered even without a storm. An empire that depends on more than one cannot endure, as experience teaches. If a second sun were joined to the fourth heaven, where our own sun shines, the earth would burn. Though this kingdom and monarchy may seem like the image of many bodies, it is but one, governed and animated by a single soul, when the members (as now) are united in preserving the whole, which is the public good. The King our lord made Your Excellency (God made it so) the captain of this ship, the soul of this body, and the sun that illumines us, knowing (as the Wise know) that in you resided the equal light required for such a role. From birth, you were as great in substance and form as you are now in action; all that was needed was a shadow to allow you, as His secondary cause, to exercise and extend the rays of your virtue across the globe. It seemed (and the world agreed) that Your Excellency's heart and spirit, like Augustus’, could hold such greatness. His Majesty daily recognizes the truth of his choice through the effects it brings. There is no one of good faith who does not wish this blessing to endure and to show gratitude to Your Excellency. I, as your most obliged servant, child of grateful servants, offer these three bouquets of Religion, Obedience, and Justice, colored with the civility that has ever cloaked Your Excellency. Though these are found in the garden of my father, open to all, there is no flower I would not cultivate especially for your service, as the universal father of the republic to whom all is owed. I humbly ask you to place them (so they do not wither) in the vessels of your grace, continuing the mercy Your Excellency has always shown us. In this, by your virtue and merits, we hope for what may be expected of so great a prince. To repay such a debt, I can only echo Ausonius: Nec tua fortuna desiderat remuneradi vicem, nec nostra suggerit restituendi facultatem ("Your fortune does not seek a reward in return, nor does ours offer the means to repay it").[10]

Juan's dedication uses metaphor and political allegory to elevate the Duke of Lerma as the divinely chosen steward of the monarchy.[50]

Prologue

In the prologue, titled Princes, Subjects, Ministers, Medrano references ambassadors from various ancient republics to introduce precepts essential for maintaining a strong and enduring republic. Medrano sought to unify twenty-one precepts to showcase the diverse yet essential precepts underlying effective statecraft. Medrano describes:

When Ptolemy, King of Egypt, was discussing matters with the most distinguished ambassadors of the most flourishing republics of that era, he requested from each of them three essential precepts or laws by which their nations were governed.[51]

Each Republic and its corresponding three precepts represents one of the seven complete treatises Medrano had already written. Only the first, on religion, obedience, and justice, was published in 1602 as the first volume of the República Mista.[10]

Twenty-one precepts of the República Mista

- The Roman ambassador said: "We Romans hold great respect and reverence for our temples and our homeland. We deeply obey the mandates of our governors and magistrates. We reward the good and punish the wicked with severity."

- The Carthaginian ambassador states, "In our republic, the nobles never cease to fight, the officials and commoners never stop working, and the philosophers continually teach."

- The Sicilian ambassador asserts, "Among us, justice is strictly upheld. Business is conducted with truthfulness. All are esteemed as equals."

- The Rhodian ambassador remarks, "In Rhodes, the elderly are honorable, the young men are modest, and the women are reserved and speak sparingly."

- The Athenian ambassador declares, "We do not allow the rich to be partial, the poor to be idle, or those who govern to be ignorant."

- The Lacedaemonian (Spartan) ambassador proclaims, "In Sparta, envy does not reign because there is equality; greed does not exist because goods are shared in common; and idleness is absent because everyone works."

- The Sicyonian ambassador explains, "We do not permit anyone to travel abroad, so that they do not bring back new and disruptive ideas upon their return; nor do we allow physicians who could harm the healthy, nor lawyers and orators who would take up the defense of disputes and lawsuits."

Medrano concludes that if these customs were upheld in a state, it would maintain its greatness for a long time. He encourages a deep study and thoughtful application of these precepts, integrating lessons from both sacred texts and historical accounts to guide governance and societal harmony.[9]

Preface

República Mista begins with a foundational 16-page preface, establishing Medrano's vision of governance through history, philosophy, and divine law. Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas, historian to Philip III, recognized its importance, advising the king that it was essential to understanding the work.[10] The preface explores the foundations of politics and society, including the progression from family to municipality, province, and kingdom. Medrano defines politics as "the soul of the city," equating its role to prudence within the human body, as it "directs all decisions, preserves all benefits, and wards off all harms." This opening lays a conceptual framework for understanding the intricate balance of governance within a mixed republic. Focusing on the three essential pillars of religion, obedience, and justice, Medrano writes:

Divine justice and human governance are so closely intertwined that one cannot exist among men without the other.[10]

Building on this conceptual framework, Medrano introduces three virtuous forms of government: monarchy, aristocracy, and timocracy, contrasting them with their corrupt counterparts: tyranny, oligarchy, and democracy in its degraded form. He explains that each virtuous form serves the public good, while the corrupt forms devolve into self-serving rule. By presenting these three opposites, Medrano reveals the need for a mixed republic that blends monarchy, aristocracy, and timocracy, creating a governance structure capable of resisting the vices of each individual system.

Drawing on historical and philosophical examples, Medrano demonstrates how this balance fosters societal harmony and stability while avoiding the pitfalls of purely singular forms of government. He argues that each system degenerates when it loses its foundational virtues and becomes consumed by selfishness or disarray. In chapter three of República Mista, on justice, he writes:

For if Kings, Councils, and Magistrates on earth are the image of God, they should also strive to imitate Him in goodness, perfection, and justice, as our superiors imitate Him to the extent of their abilities, in order to induce true piety and virtue to those under their charge with their example (which is the most powerful thing). For just as the heart in the body of animals always remains the last to corrupt, because the last remnants of life remain in it, it seems appropriate that, having some illness entered to corrupt the people, the Prince and Magistrates remain pure and unharmed until the end.[50]

Monarchy

Medrano views monarchy as the most natural and cohesive form of governance. A single ruler, he argues, provides unity and decisiveness, ensuring that decisions are made in the interest of the entire state. He draws on philosophical reasoning, quoting Aristotle's assertion that "a multitude of rulers is not good," and emphasizes that a virtuous monarch must prioritize the public good over personal gain. However, Medrano warns of monarchy's potential to devolve into tyranny if power becomes unchecked or if rulers lack moral integrity. Medrano identifies monarchy as the closest reflection of divine governance, citing the singularity of God as the ideal for unity and authority:

As there is one God, creator and ruler of all, so should there be one prince, governing with wisdom and justice... the governance of one represents the order of nature, by which all things are reduced to a primary ruling principle, just as all celestial orbs and moving things are ordered by the prime mover. Hence, we observe in the universe a single God, creator and governor of all (Rex Deus quifpiam humanus est); in the bees, one queen; in the flock, one shepherd. And for the sake of peace and the preservation of all things, what is more appropriate than to concentrate power in a single ruler?[10]

A monarch, he argues, must emulate divine virtues, prioritizing the common good over personal desires. Medrano warns, however, that monarchy can devolve into tyranny if the ruler strays from these virtues, emphasizing the need for piety and humility to align earthly authority with divine will. Regarding tyranny, he states, "A tyrant governs not for the people, but for his own desires, treating the state as his possession rather than a sacred trust." Tyranny arises when a monarch abandons justice and piety, becoming an oppressor rather than a protector.

Aristocracy

Aristocracy, the governance by the virtuous, is extolled by Medrano for its focus on wisdom, experience, and the common good. He presents historical examples like the governance of Sparta, which achieved remarkable longevity and stability through a carefully structured aristocratic system. Medrano acknowledges that aristocracy is most effective when it selects leaders based on merit rather than privilege, but he cautions against its corruption into oligarchy, where power serves a narrow, self-serving minority. In aristocracy, Medrano sees the potential for collective wisdom and virtue to govern effectively. He compares the selection of aristocratic leaders to the idea of God entrusting His divine work to angels, revealing the importance of moral integrity and expertise:

Just as God surrounds Himself with those who serve Him faithfully, so too must an aristocracy be composed of virtuous and capable individuals.[10]

Medrano acknowledges that aristocracy risks corruption into oligarchy if power is used for selfish ends rather than the public good. Such a system exploits the many for the benefit of the few, undermining the harmony of the state. He necessitates a divine moral framework to guide these leaders. Oligarchy, Medrano contends, is the result of aristocracy corrupted by greed and self-interest, stating that:

Oligarchy is nothing more than a conspiracy of the wealthy against the public, using power to advance their fortunes at the expense of justice.[10]

Timocracy

Timocracy, which Medrano defines as governance by individuals of moderate wealth and merit, occupies a middle ground between monarchy and aristocracy. Drawing on Aristotle's insights, Medrano notes that this form of governance ensures that neither extreme wealth nor poverty dominates, fostering a more equitable society. However, he notes that timocracy is vulnerable to instability when personal interests outweigh collective responsibility. Medrano regards timocracy as a governance system rooted in moderation and equity, drawing parallels to God's justice in rewarding virtue and punishing vice. He writes:

Cities are well-governed when power rests in the hands of those with sufficient means to be invested in the public good without succumbing to greed... God's governance is neither arbitrary nor excessive, but measured and fair—qualities that must define a timocracy.[10]

This form of government relies on individuals with sufficient means and merit to serve the public interest without succumbing to greed. Medrano warns, however, that without divine principles to temper human ambition, timocracy can degenerate into chaos or selfish governance. Timocracy's opposite, Democracy, which he calls "a depraved form of republic," while acknowledging its appeal to liberty, is described as unstable and prone to excess. Medrano writes:

When the multitude rules unchecked, their passions replace reason, and the state suffers from the clamor of conflicting desire.[10]

Medrano warns that unchecked democracy, though appealing in its promise of liberty, can easily descend into mob rule (ochlocracy), where fleeting passions overpower reason and governance becomes erratic.

Mixed Republic

Tomás Fernández de Medrano's vision culminates in the concept of a mixed republic, where the strengths of monarchy, aristocracy, and timocracy are interwoven to create a balanced and enduring system. For Medrano, only a divinely guided mixed republic can sustain lasting stability, equity, and justice, anchoring human governance in the civil, natural and divine laws of God:

From these three forms, philosophers composed a mixed Republic, saying that any form of Republic established on its own and in simple terms soon degenerates into the nearest vice if not moderated by the others; and that, to sustain Republics in proper governance, they must incorporate the virtues and characteristics of the other forms, for none of them fears excessive growth that might lead it to incline towards its closest vice and consequently fall into ruin. For this reason, many ancient and modern thinkers have held the view that the Republics of the Lacedaemonians, Carthaginians, Romans, and other renowned Republics were composed and justly blended from Royal, Aristocratic, and Popular powers. To avoid any confusion or ambiguity, we can say that if authority lies in a single Prince, the Magistracy is a Monarchy, as in Spain, France, Portugal, and (in earlier times) England, Scotland, Sweden, and Poland. If all the people have a share in power, then the State is popular, like in Switzerland, the Grisons, and some free cities of Germany. If only the smallest portion of the people hold power (as in Venice, where it's held by the nobles, and in Genoa, by the twenty-eight families), it is called a Signoria, and the State is Aristocratic, as it was with the Romans, the Athenians, and many other republics that flourished most when they incorporated elements of both popular and aristocratic governance. Although time's injuries and the malice of people may strain the form of any of these governments against its own nature, its essence does not change even if it acquires a different quality.[10]

He praises historical examples like the Roman Republic, which successfully blended these elements to achieve remarkable governance. "Republics that integrate the virtues of multiple systems of government," Medrano argues, "achieve a balance that guards against the excesses of any single form." For Medrano, power must always be tempered with virtue. He advocates for a governance structure that unites the authority of monarchy, the wisdom of aristocracy, and the equity of timocracy, ensuring that justice, stability, and prosperity endure.

At the core of his doctrinal framework lies a divine principle: just as God's singularity is absolute, so too must governance uphold unity, justice, and moral accountability. Medrano asserts, true leadership requires a reflection of divine virtues. Authority must not be wielded arbitrarily but must align with God's justice, shaping a government that is not only permissible but enduring. He writes:

As one ancient writer said, a prince should serve the same God, observe the same law, and fear the same death as his subjects. For in the end, all things of this world pass away, consumed by the flow of time, and when they reach their peak, their greatness and state come to an end. The Creator has set this law, so that men do not become arrogant, believing their kingdoms to be eternal, and thus realize that they are made of matter subject to celestial and incorruptible causes.[52]

Chapter one: Religion

The first chapter of República Mista, which begins on page 17, establishes religion as the cornerstone of governance and societal harmony:

To begin at the true beginning, with the origin and end of all things, God, I will illustrate the importance for Princes to recognize this Supreme Majesty. In obedience and reverence, they must recognize that they, too, are His creatures, subject to His laws and divine will, just like everyone else. For the example of faith that they set becomes a law and a model for their subjects, fostering a society rooted in love and charity. This is the surest path to preserving, expanding, and fortifying the realms and borders of their kingdoms and empires.[10]

In the religion chapter of Republica Mista, Tomás Fernández de Medrano argues that religion is the essential foundation of all civil governance. He draws from natural philosophy to show that everything, from celestial bodies to human societies, follows a divine order, stating: "This entire lower world obeys the higher, governed by it as a secondary cause."[4] Medrano insists that even the most isolated or undeveloped societies possess "some specific order, arrangement, and agreement... and some awareness of the divine,"[4] noting that no people exist without customs, laws, or spiritual practices. He sees this universal inclination toward religion as evidence of its necessity in human affairs. Citing Plutarch, he writes: "A city might sooner do without the sun... than without some establishment of law or belief that God exists and upholds creation."[53] He connects divine justice and human governance as inseparable, arguing that "one cannot exist among men without the other."

For Medrano, religion precedes and enables laws, obedience, justice, and the cohesion of republics. He praises ancient lawmakers Lycurgus, Numa Pompilius, Solon, and others for instilling reverence for the divine, noting that fear and hope in the gods secured social order and civic duty.

He quotes Aristotle in asserting that religion is natural to mankind and vital to leadership: "It is necessary that the prince... be esteemed as religious... for subjects more easily endure hardship when they believe rulers have the gods on their side." Medrano surveys religious practices across cultures, from Egyptian sacrifices to Phoenician sky worship, to show that "all are moved by religion," quoting Cicero: "They believe that they must diligently worship and uphold the ancestral gods." He also recounts Roman reverence for the divine, quoting Cicero and Virgil to highlight how "piety preserved the republic." In contrast, Medrano laments that when the Athenians, under the influence of skeptics like Protagoras and Diagoras, "began to show contempt for God and His ministers," their republic declined. The rise and fall of states correlate directly with the respect shown to religion and its institutions, warning: "No fault is greater than that of one who does not know God."[1]

Religious Legitimacy and the Moral Foundations of Rule

In Republica Mista, Tomás Fernández de Medrano emphasizes that the prosperity and stability of monarchies are deeply tied to fidelity to their faith and their reverence for religious authority. He credits the expansion of the Spanish monarchy to the devoutness of its rulers, writing that since they "began to enjoy the special protection of the Holy Apostolic See," they have prospered by "persecuting the enemies of our holy faith." He recounts the story of King Alfonso the Chaste, whose devotion led to divine miracles, such as the appearance of angels crafting a jeweled cross, which affirmed Spain's sanctified imperial mission. In contrast, Medrano attributes the decline of France and England to their betrayal of religious fidelity: "By scorning the Apostolic See, the supreme pontiffs, and the Catholic faith," the English monarchy brought ruin not only to itself but also to Scotland and other allied nations.

He describes the sacredness of religious spaces, citing Theodosius and Valentinian's decree that "those who forcibly remove anyone seeking refuge in the church should be punished with death," affirming that "one should be safer under the protection of religion than under arms."

Throughout, Medrano insists that true political order rests on respect for divine law, warning against rulers who disguise ambition with false sanctity. "Nothing is more deceptively attractive than false religion," he quotes Livy, "where the divine power of the gods is pretended to cover wickedness." He condemns the use of religion to justify factionalism and civil war, invoking the chaos caused by false prophets and reformers across Europe.

Medrano praises historical examples like Numa Pompilius, who instilled fear of God into a warlike people, showing that:

if such a religious prince had not succeeded Romulus, the Roman people would have become uncontrollable and violent.

A prince, he argues, must be:

truthful and perceived as truthful, since no power gained by crime is enduring.

He acknowledges that rulers may need to practice discretion in politics, but always within bounds: "Nothing must be done against faith, charity, humanity, or religion." According to Medrano, the prince's word, once given, should be as unbreakable as divine law:

His word should be as true, certain, constant, and reliable as the word of God.[50]

Medrano warns that "God despises those who are false and deceitful," and sees the rise of corrupt rulers as divine punishment: "The Holy Spirit will make a hypocrite ruler as punishment for the sins of the people."[4] Ultimately, he argues, religion is not merely personal but foundational to legitimate rule, and any governance that opposes it is destined to fail.

Oration of the Duke of Savoy

In his Republica Mista, Tomás Fernández de Medrano, Secretary of State and War to Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy, recounts a powerful oration delivered by the Duke to the people of Thonon and surrounding territories, urging their return to the Catholic faith. The Duke appeals to religious tradition and loyalty, asking:

If the lord has the authority to command his vassals... how much more so in matters that serve [God], glorify Him, and are for your own good?[4]

The 11th Duke of Savoy reminds them of their six-hundred-year history under Catholic rule and laments their departure into heresy, "living as heretics, though they claim the name of Christians." Appealing to history, doctrine, and royal duty, he urged his subjects to reject false religions and remain loyal to the Church of Rome, warning that religious division undermines both faith and sovereignty. He invoked ancestral loyalty, the sanctity of the sacraments, and the divine role of Catholic monarchs to defend orthodoxy and civil peace:

There is one true religion, just as there is only one true God; all else is ruin.[10]

With this declaration, the Duke of Savoy aligned his rule with divine order, asserting that those who abandon the Catholic faith ally themselves with disorder, sedition, and spiritual death. His words sparked widespread repentance, restoring allegiance among towns, nobles, and clerics across the region.[4] The oration denounces sectarianism and warns of the civil disorder it causes, citing examples such as Münster, La Rochelle, and Geneva, which became "fortresses of the devil within Christendom." The Duke emphasizes that a prince who does not preserve the Catholic faith cannot expect to retain true sovereignty: "If the Catholic religion is not protected... it will be all too easy for another to take its place."

He invokes historical and biblical authorities to reinforce that rulers must serve and uphold divine law to maintain peace and legitimacy. Medrano, personally witnessing the Duke's address, affirms its transformative power: "This had such an impact on the minds of everyone that all begged for mercy." He praises the Duke's personal piety, military rituals, and protection of religious institutions, presenting him as an ideal Catholic ruler who embodies Cicero's maxim: "In every republic, the first care is for divine matters." In República Mista, the Duke's oration stands as a practical illustration of Medrano's codified doctrine, affirming that true sovereignty requires harmony between political authority and religious devotion, with rulers acting not only as temporal governors but as defenders and nurturers of the Catholic faith.[1]

Religious Order and the Threat of Sectarian Sedition

In República Mista, Tomás Fernández de Medrano presents the defense of Catholic religion not only as a spiritual necessity, but as a cornerstone of republican stability. Among the most serious threats to the health of a republic, he argues, are not only external wars but internal seditions that disguise themselves in the form of religious zeal. When princes fail to uphold the true faith with vigilance and reverence, they leave space for sectarian movements to arise. These movements frequently shelter individuals who are fugitives from justice, political opportunists, or enemies of lawful order.

Citing Aristotle's Politics, Medrano writes:

"Fear breeds seditions, for as many commit crimes to avoid punishment as do so to strike first before others strike them." (Et metus seditiones movent, tam enim qui fecerunt iniurias metuentes poenam, quam ii qui infens expectant, praevenire volentes, priusquam ea inferatur.)[11]

According to Medrano, many such factions form under a pretense of persecution. They use religious justification to mask personal ambition or resentment. These groups often organize around a single charismatic leader, frequently one of humble or illegitimate origin. United in defiance of lawful authority, they seize towns or fortresses and proclaim rival republics built upon rebellion.

He identifies the Anabaptist seizure of Münster as a prime example, describing the great effort undertaken by Emperor Charles V and the ecclesiastical princes to suppress what he regarded as a heretical regime. He adds the examples of La Rochelle and Montauban in France, which fell under the control of the Huguenots, and Geneva under the Calvinists. He considers all of these cities to be fortresses of error, where rebellion and disorder persisted against rightful monarchy.

Medrano warns that wherever the Catholic religion is not upheld with strength and reverence, destructive doctrines will take root. A prince who neglects the true faith cannot expect to retain real authority, as sectarian factions will eventually challenge his sovereignty and limit his power.

A prince can be certain that if the Catholic religion is not protected and cherished as it should be in his dominion, it will be all too easy for another to take its place. And once another religion has taken hold, he cannot freely call himself lord of that province, for he will remain dependent on it all his life.[11]

From such disorder follows licentiousness, impiety, and division. These forces gradually undermine the body politic. For Medrano, no republic can endure without religion, and no military power can remain strong if the soul of the nation is weak. Religion and law must remain united if political order is to be sustained:

If an empire lacks a strong religion, it is impossible for it to be powerful in arms. Without these two things, it must fall. But if they remain united, as they do in this Monarchy, then it will live and stand for a thousand ages.[11]

This duty of preserving religious and political unity belongs above all to the sovereign.

"Who does this duty belong to more than the prince? It is fitting that what is best be honored by the best, and that what rules be served by the ruler." (Ad quem autem ea potius quam ad Principem pertinet? Decet enim quod optimum est, ab optimo coli, quod imperat, ab imperante.)[11]

Medrano concludes by affirming the enduring legitimacy of the Catholic faith. He contrasts its divine origin and spiritual fruitfulness with the false religions of apostates and pagans, which endure only through ignorance or rebellion:

If the false religions of apostates and pagans could sustain themselves for so long, and still persist in some places as good religions in the eyes of the ignorant and the blind, what hope can we not place in our true religion? It pleases and delights our God, from whom it originates, and to whom we owe our being, preservation, and the abundance of goods He so generously provides to both the good and the bad.[11]

Piety, superstition, and the power of belief

In Republica Mista, dedicated to the 1st Duke of Lerma, Tomás Fernández de Medrano, contrasts genuine religious devotion with the dangers of superstition and false belief. He praises figures like Francisco de Sandoval, Duke of Lerma, who, despite his immense power, invested in sacred architecture and remained mindful of mortality.

Medrano also highlights the zeal of Charles Emmanuel I of Savoy, who instructed his secretary to prioritize any matter that served both God and the king. These leaders, Medrano suggests, exemplify the ideal union of power and piety. When advised to act militarily against foreign alliances, Savoy replied that Spain's strength lay in having "a very Catholic king, a true friend of God," whose faith alone could secure divine protection.

He presents historical examples, from the Hebrews who defied Emperor Caligula, to Christian martyrs, and even pagan figures like Calanus the Indian philosopher, to show the enduring strength of belief. Even misguided religions, he argues, have inspired profound sacrifice: "Nothing rules the masses more effectively than superstition," he quotes Quintus Curtius, warning that uneducated people are particularly vulnerable to false wonders and omens.

For Medrano, true religion must be distinguished from superstition and astrology, which he condemns as deceitful distractions. Superstition, he says, is "empty appearance and false imagination," and leads people away from divine truth. He denounces judicial astrologers for misleading the public, undermining reason and faith alike. Citing authorities like Pico della Mirandola, Aquinas, and Varro, he warns that only through proper reverence and obedience to divine law can virtue, faith, and courage be sustained.[4]

Patria

The concept of Patria (love and duty to one's Fatherland) is not an abstract idea by Tomás Fernández de Medrano in his República Mista, rather it was lived by Spain and his ancestors. The town of Medrano, La Rioja, bears not only the name but the arms of the noble House of Medrano, from which it descends. The heraldic motto: "To die for Faith, King, and Patria is glorious," reflects the enduring legacy of the family's doctrine, embedded in the municipality's civic identity since its first recorded donation in 1044.[55]

In the Religion chapter of República Mista, Tomás Fernández de Medrano presents Patria (love and service to one's homeland) as a sacred duty, rooted in natural affection, divine law, and moral conscience.[11]

Drawing on ancient and biblical examples, he argues that:

Every person is obligated to serve and aid the public good... for within its welfare lie the life, honor, and prosperity of each individual.[56]

Medrano recounts the story of Nehemiah, who was moved to tears upon hearing of Jerusalem's desolation and was granted royal support to rebuild his city. He cites Cicero, who said: "All affections are encompassed in our homeland, for which any noble person would seek death if it would be beneficial."

Examples such as Cato the Younger, who resisted unjust laws and rejected political alliances that compromised the Republic, show that true loyalty lies in justice and conscience: "Our conscience and the immortal gods are given to us, and they cannot be separated from us."

The chapter continues with patriotic acts across history: El Cid, despite exile, served Castile with valor; Juan Mendez of Évora opposed unjust taxation and was later vindicated by the king; and Lycurgus bound Sparta to his laws even after death. Medrano also recalls Codrus, who gave his life to ensure Athens' survival, asserting that "to die for virtue is no death at all."

He praises Spain's Catholic monarchs for defending the faith, founding churches, and extending the Gospel to distant lands. In particular, he honors Philip III for upholding the Inquisition as a "mighty shield and sacred institution." Medrano concludes that the strength of a kingdom depends on its moral and spiritual foundations, quoting Seneca: "Where there is no regard for law, holiness, piety, and faith, the kingdom is unstable."

Ultimately, he argues that good governance aligns with religious principles, embodying truth and virtue to earn the people's trust and God's favor, as only He bestows and withdraws power: "The Lord changes the times and seasons; He raises and deposes kings," quoting Daniel 4.[4]

Chapter two: Obedience

Introduction to the Second Chapter

Before the second chapter of República Mista, Medrano begins with an introduction on obedience, and a meditation on the necessity of obedience for both spiritual life and civil harmony. Medrano opens by quoting Seneca: "Our minds, like noble and generous horses, are better governed with a light rein." He asserts that if even the ancient Persians taught their children to "love, obey, and revere their princes and magistrates," then Christians should not neglect what even pagans held as sacred.

He argues that the strength of the Roman Republic rested on this precept, and that Christians, called to serve and revere God, must likewise obey their earthly rulers. Obedience to Kings, Councils, and Magistrates, he writes, flows naturally from the teachings of the fourth commandment and should be instilled from the earliest age. Medrano's doctrine is deeply rooted in Spanish-Arabic tradition and serves both as a reminder to the wise and a guide to the unknowing. He closes the introduction with a pointed reflection:

To give counsel to a fool is an act of charity; to give it to the wise, one of honor; but to offer it in times of depravity, an act of wisdom.

Obedience to Princes and Magistrates

The second chapter of República Mista, which begins on page 69, elaborates on the importance of obedience to princes and magistrates as a safeguard against disorder and rebellion. Medrano states:

If knowing how to govern well is the most effective preventative against corruption, then knowing how to obey well which is crucial among the people, is of even greater importance. Where obedience is lacking, order is lost, and disorder takes its place. The most important and advantageous quality that has been preserved in these kingdoms is the high regard we have always held for councils, magistrates, ministers, judges, and public officials, recognizing them as men placed there by the hand of God. For this reason, we honor and respect them as representatives of divine rule over all creatures. Just as the Almighty in His glory has created an order among beings (setting some to serve and others to govern) and placed certain stars in the heavens to shine more brightly than others, as a symbol of His divinity, with the Sun itself illuminating, warming, and nurturing all things on earth for humanity's use, so too He wished that the supreme councils and magistrates in cities, provinces, and kingdoms would shine by virtue of their excellence.[57]

Quoting Erasmus, Medrano affirms: "To command and to obey are two things that keep sedition away from citizens and ensure concord." He compares a well-ordered kingdom to a body where the ruler is the head and the law its soul, insisting that "where obedience is lacking, order is lost, and disorder takes its place."

Medrano recounts that Sparta's success was not due to the wisdom of its rulers, but because "the citizens knew how to obey." He argues that Spanish unity and prosperity result from a careful balance of powers, ensuring that neither nobility nor commoners dominate, sustained by reverence for public officials as "men placed there by the hand of God."

He stresses that kings must be honored as God's representatives, with respect extended also to their ministers and councils. "This authority," he writes, "is the true source of their greatness... achieved not through intelligence, but through honoring the king and the realm."

Drawing heavily on sacred Scripture, Medrano cites Romans 13, Titus 3, and 1 Peter 2, reinforcing that "there is no power but from God," and that resisting rulers is resisting divine order. Subjects must obey not out of fear alone, but "for conscience' sake." As Tacitus writes, "There can be no peace without arms, no arms without pay, and no pay without taxes." He adds, "Render tribute to whom tribute is due... honor to whom honor."

Medrano also reflects on the burdens of rulership, writing: "While we sleep, they remain vigilant... they carry the weight of countless souls under their dominion." He quotes Seleucus: "If one truly knew the weight of a scepter, they would not have the courage to pick it up."

He warns against slandering magistrates, stating that "no one should judge the actions of Councillors... but the Prince himself," and praises emperors like Augustus and Vespasian for the honors they showed to senators. Vespasian declared: "I can respond to the injuries they commit, but [subjects] are not allowed to speak ill of them." He asserts that obedience, respect, and prayer for rulers are not only civic duties but sacred obligations that sustain both peace and divine order.

Ministers, Obedience, and Counsel

Medrano expands the concept of obedience to include reverence for the ministers and servants of kings, particularly those close to court. He affirms the high dignity historically granted to officers such as the Reyes de Armas (Kings of Arms), describing their role as "a profession akin to the heroic," with privileges dating back to Bacchus, Alexander the Great, Augustus, and Charlemagne. These included safe passage, exemption from common duties, the authority to judge dishonor, and the honor of wearing royal insignia. Such prerogatives, he argues, show that even humble servants of the king "are invested with mysteries," and should be respected accordingly. Medrano writes:

In my view, both the counselor and the realm will be fortunate when such a servant and confidant possesses qualities worthy of the royal station they serve, especially when their innate nobility and virtues align with the dignity required for such a role. Where noble lineage and habit join with noble actions, there can be no doubt of their merit. And when this is accompanied by piety, goodness, and holiness—as we see, experience, and witness in our time—such virtue indeed stands as a model worthy of our admiration and emulation, does it not?[10]

Medrano cautions private individuals against interfering in public governance, stating that reform must come through proper authority. "No public display should be made," he writes, advising that concerns be directed to lawful superiors. Those who carry out the will of the prince, he says, "are his hands," and as such, are owed honor and obedience.

Quoting Plautus, "What a king does should be considered honorable; it is the duty of subjects to obey," he defends rulers against misjudgment by the ignorant, stating that "what is done piously by the good is often judged as cruelty by the wicked." Empire, he writes, brings envy and misunderstanding, and "the reward... is to be maligned." Yet true rulers focus on justice and the common good, trusting that over time, their deeds will be recognized.

He contrasts the harsh Locrian law, where lawmakers faced execution for failed proposals, with Mecenas's advice to Augustus: "Praise and honor those who offer sound counsel... but neither disgrace nor accuse those who err." Moderation and prudence, Medrano insists, are essential in courtly matters.

He praises those counselors who temper princes' passions and offer discreet, virtuous guidance. "No wise and great prince has ever lacked a trusted confidant," he writes, naming Calisthenes, Panaetius, and others who brought wisdom and glory to their rulers. When such figures possess noble lineage, wisdom, and piety, they serve as "a model worthy of admiration and emulation." This understanding of obedience and royal council served as a justification for the valido in Habsburg Spain.[46]

Types of Authority and the Dangers of Flattery

In República Mista, Tomás Fernández de Medrano distinguishes between two types of authority: one supreme and absolute answerable only to God, and the other subordinate and bound by law, exercised by magistrates for a limited time under royal commission. The supreme prince, he writes, "acknowledges none greater than himself (after God)," and magistrates derive their authority from him and remain subject to his laws.

Medrano affirms that individuals must obey these powers in all matters not contrary to divine or natural law, even when commands seem unjust: "They should not judge their judges." The supreme magistrate is likened to "a father to the kingdom," tasked with maintaining peace, justice, and the common good.

He warns, however, of the widespread aversion to tyrants and the ease with which rulers who lack visible virtue may fall into contempt. Yet Scripture teaches obedience even to corrupt rulers, as they act as "instruments of [God's] wrath, punishing the people's wickedness." He quotes, "When God is angered, the people receive such a ruler as they deserve for their sins."

Citing Tacitus and Augustine, Medrano illustrates how power can corrupt even the seemingly virtuous. Tiberius, Nero, and Galba are presented as cautionary examples, men who ruled poorly despite early promise. "Things feigned cannot last long," Augustine warns.

Flattery, more than open enemies, is seen as the chief corrupter of rulers. Those "who make it a habit to praise all things in their rulers, be they virtuous or vicious," erode truth and judgment. Tiberius lamented: "Oh, men prepared for servitude!" Medrano recounts how Caesar, influenced by a flatterer, "came to a miserable end."

He writes: "Flattery has overthrown more than the enemy," criticizing courtiers who, instead of offering honest counsel, enable a prince's whims to serve their own gain.

Obedience to rulers, just or unjust

In República Mista, Tomás Fernández de Medrano contends that obedience and reverence are due to all rulers, whether just or unjust. "Let the good not be scandalized to see the wicked exalted," he writes, asserting that the rise and fall of kings is governed by divine providence. Drawing on Daniel 4, he declares: "The Most High is sovereign over the kingdoms of men... and sets over them the lowliest of men," emphasizing that even seemingly unworthy rulers are chosen by God for a purpose.

Medrano cites the example of Nebuchadnezzar, whom God rewarded with Egypt despite his tyranny, and King Amasis of Egypt, who overcame public contempt for his humble origins through strength and wisdom. From 1 Samuel 8 to Jeremiah 27, Medrano presents biblical arguments for unconditional obedience: "I have handed over all these lands to my servant Nebuchadnezzar... all nations will serve him." He urges subjects to trust that God raises kings not only to reward the good but also to punish the wicked.

He praises the historical patience of Christians under pagan and heretical rulers such as Nero, Julian the Apostate, and Diocletian, highlighting their peaceable endurance. Even David refused to harm King Saul, affirming: "Who can lay a hand upon the Lord's anointed and be guiltless?" Medrano cites both religious and legal prohibitions against cursing rulers, warning that murmuring against authority invites divine judgment.

The duty of a good subject, he insists, is to remain "humble, gracious, obedient, and devout," without aspiring beyond their station. Those who suffer under harsh rule should interpret it as a correction from God: "I will give you a king in my anger" (Hosea), and endure it with prayer and patience, trusting that "He who wounds also heals."

Medrano explains that rulers hold Regalia, symbols of sovereign authority which entitle them to create and enforce laws over all subjects. These Regalia are expressed through eight primary points, which, when properly observed in practice, ensure public obedience and preserve the order and stability of the realm.[50]

The Eight Royal Prerogatives and Limits of Public Judgment

In República Mista, Tomás Fernández de Medrano outlines eight primary prerogatives, or Regalia, that define sovereign power:

- To create and repeal laws

- To declare war or establish peace

- To act as the highest court of appeal

- To appoint and remove high officials

- To levy and collect taxes and public contributions

- To grant pardons and dispensations

- To set or alter currency and its value

- To require unconditional oaths of loyalty

He argues that rulers may exercise these powers directly or through delegated ministers and must not be disrespected, even when their administration is imperfect. Their authority, Medrano states, is divinely instituted and must be regarded as sacred:

Established by God through countless decrees and testimonies, this authority ought to be respected and held as a source of majesty.[50]

Subjects, he asserts, should not scheme against their superiors or question their actions. Public calamities, such as famine, plague, or war, should not be attributed to rulers without clear evidence. "One is not to be condemned if their thoughts are not laid bare," he quotes, warning against judging secret intentions or mistaking natural events for political failure.

Royal Virtue and the Nature of Public Speech

Medrano reaffirms that discretion, obedience, and reverence are owed not only in action but in speech and silence. Drawing on the example of Otho, he writes: "Tam nescire quædam milites, quam facere oportet"–"It is as necessary for soldiers to be ignorant of certain things as it is for them to carry out their duties." Just as commanders do not divulge all plans to their soldiers, who face constant danger, private citizens, even less so, should seek to uncover the secret intentions of princes.

Echoing Seneca's wisdom, "Qui plus scire velle quam satis sit; intemperantiæ genus est" ("To wish to know more than is sufficient is a kind of excess"), Medrano argues that excessive curiosity disrupts peace and loyalty. Silence and obedience are therefore "powerful means of attaining peace," reminding subjects that this world is not their final home, therefore:

The loyalty and silence of subjects toward their king and rightful lord, and toward his councils and magistrates, are crucial virtues within the populace and powerful means of attaining some peace in this life. This peace reminds us that it is not our permanent home nor our final destination and is best suited to remind us that we live and journey toward an eternal life, not this fleeting, mortal, and transitory one.[58]

In República Mista, Medrano contemplates the mortality of even the greatest monarchies, emphasizing the need for prayer and moral vigilance. Within this reflection, he elevates Philip III of Spain as a living embodiment of Christian kingship, whose reign aligns with divine order and the spiritual duties of sovereign rule.