Parankylosauria

| Parankylosaurs Temporal range: Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

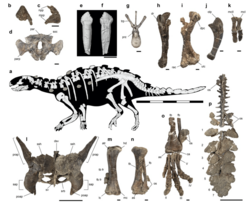

| Fossil material of Stegouros, a parankylosaur | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Thyreophora |

| Clade: | †Ankylosauria (?) |

| Clade: | †Parankylosauria Soto-Acuña et al., 2021 |

| Genera | |

Parankylosauria is a group of armored thyreophoran dinosaurs known from the Cretaceous of South America, Antarctica, and Australia. Most analyses place parankylosaurs as a member of the Ankylosauria, in which case the group would have split from other ankylosaurs during the mid-Jurassic period, despite this being unpreserved in the fossil record. Another analysis has proposed that parankylosaurs are instead a distinct lineage of non-ankylosaurian armored dinosaurs with more ancestral anatomy. Several parankylosaurs are characterized by a distinctive frond-like tail weapon (called a 'macuahuitl'), made of several fused osteoderms projecting outward.

History of research

During the Mesozoic era, the southern continents (South America, Antarctica, Australia, and Africa in addition to India and Zealandia) were unified into a supercontinent known as Gondwana. This was in contrast to the supercontinent of Laurasia in the Northern Hemisphere, with both originating from the breakup of Pangaea. Gondwana itself gradually split apart over the course of the Jurassic and Cretaceous eras.[1] Ankylosaurian dinosaurs from Laurasia have historically been far more extensively recorded and studied. Reports of the group in Gondwana date back to 1904, with a specimen from Australia and include referrals of Loricosaurus, Lametasaurus, and Brachypodosaurus to group among assorted fragmentary material.[2] Much of this material including would later be shown to be misidentified and not belonging to ankylosaurs, including the named genera.[2][3][4] The first definitive ankylosaur to be recognized from Gondwana was discovered in Australia in 1964 and later named in 1980 as Minmi paravertebra.[2] The possibility of a biogeographic connection between South America and ankylosaurs in Australia was raised alongside discovery, though based on conjecture.[5]

Ankylosaurs from Gondwana have remained very mysterious. Fossil material continues to be scant, and southern taxa have been difficult to interpret in a phylogenetic context. Vertebrae of Antarctopelta from Antarctica, for example, were so foreign compared to those of euankylosaurs that it was questioned if they might instead belong to a marine reptile, which would make the genus based on a chimeric specimen. The discovery of the genus Stegouros, published and named in 2021, helped to clear up the previous confusion. The type specimen of the genus preserved enough of the skeleton to make it clear that there was a previously unrecognized monophyletic grouping of these southern ankylosaur taxa. Thus, the study naming the genus, by Sergio Soto-Acuña and colleagues, coined Parankylosauria based on the two aforementioned genera and Kunbarrasaurus. The name, referencing its parent group, means "at the side of Ankylosauria".[6]

The Parankylosauria may not have been the only Gondwanan ankylosaurians; Patagopelta was described from Argentina in 2022, and has been found to be closely allied with North American nodosaurids in the subfamily Nodosaurinae. This would suggest that in addition to the more ancient Parankylosauria, more derived euankylosaurians also inhabited South America, having migrated from North America as part of a biotic interchange during the Campanian.[7] However, more recent studies have suggested a parankylosaur affinity for Patagopelta.[8][9] In one of their analyses, Fonseca et al. (2024) recovered the enigmatic thyreophoran Jakapil as a basal ankylosaur, sister to both Parankylosauria and Euankylosauria. They noted that it took four steps in their analysis for Jakapil to fall within the Parankylosauria—a placement that should not be disregarded—though this is not the most parsimonious position.[10]

Anatomy

Known members of Parankylosauria are all small animals, ranging from 1.5–4.0 metres (4.9–13.1 ft), and possessed proportionally large skulls. The most distinctive trait of the group is their macuahuitl, named after the mesoamerican weapon of the same name. This trait is similar to the thagomizer of stegosaurs and tail clubs known in ankylosaurines, though evolved independently from each. This was a structure at the end of the tail formed by a series of five pairs of robust osteoderms (bones in the skin) fused together, surrounding the sides of the tail and surrounding the entirety of it near the tip. This weapon is known directly in the genus Stegouros, suspected based on indirect evidence in Antarctopelta, and not confirmed in Kunbarrasaurus, for which a complete tail is not known. In the former taxon, the weapon is associated with dramatic shortening of the tail, made up of far fewer vertebrae than any other kind of thyreophoran. As with many other members of this group, osteoderms would have covered much of the body of parankylosaurs, functioning as spiny armor.[6]

Parankylosaurs, compared to the more well-studied euankylosaurs, retain more traits seen in more primitive thyreophorans and stegosaurs. This is most applicable in the body, most distinctively seen in the possession of rather long and slender limbs. The skull, comparatively, is more similar to that of other ankylosaurs, thought to indicate the acquisition of advanced skull traits earlier in ankylosaur evolution. Also, unlike euankylosaurs, it is thought, based on the preserved osteoderms of Kunbarrasaurus and lack of flank osteoderms associated with other known genera, that parankylosaurs may have had rather light coverings of dermal armor compared to their relatives. They possessed a pelvic shield, formed from a thin sheet of bone over the hip region, more reinforced than the superficial shielding of stegosaurs but not as overbuilt as those found in euankylosaurs.[6]

Classification

André Fonseca and colleagues in 2024 formally defined this clade in the PhyloCode as "the largest clade containing Stegouros elengassen, but not Ankylosaurus magniventris and Nodosaurus textilis". This definition ensures both ankylosaurids and nodosaurids are excluded from Parankylosauria.[10] The following cladogram is reproduced from the phylogenetic analysis in the 2021 study by Sergio Soto-Acuña and colleagues:[6]

In 2026, Agnolín and colleagues described several skeletal elements from the Allen Formation of Argentina that they referred to Patagopelta cristata. While this species was initially described as a nodosaurid in 2022,[7] later analyses and discussions preferred parankylosaurian affinities.[9] To test the relationships of Patagopelta, Agnolín et al. added it to the phylogenetic matrix of Raven et al. (2023), a dataset designed to test the relationships of all armored dinosaurs,[11] which had not previously sampled parankylosaurs in detail. Due to this lack of taxon and anatomical character sampling, earlier published iterations of this dataset, which included some traditional parankylosaur taxa (e.g., Patagopelta and Kunbarrasaurus), failed to recover them in a single monophyletic clade.[12] Using an updated version of this matrix, Agnolín et al. (2026) conducted their phylogenetic analysis under equal weighting (Topology A below) and implied weighting (Topology B below). Both versions recovered a monophyletic Parankylosauria, comprising Stegouros, Antarctopelta, Patagopelta, Kunbarrasaurus, and (for the first time) Minmi. Their implied weights analysis also recovered Yuxisaurus, a Jurassic thyreophoran from China, as the earliest-diverging member of the Parankylosauria, a result that has poor statistical support but is based on two shared anatomical characters. This is also consistent with earlier discoveries of relatives of Cretaceous dinosaur taxa from the Southern Hemisphere in Jurassic/Early Cretaceous rocks in China. More surprisingly, both analyses recovered Parankylosauria outside of its traditional placement within Ankylosauria. Instead, it was placed as the sister taxon to Eurypoda (ankylosaurs + stegosaurs) or in an unresolved polytomy with these clades and Yuxisaurus. The authors argued that Parankylosauria should be regarded as a lineage distinct from Ankylosauria, in part due to many plesiomorphic ('ancestral') traits in parankylosaur skeletons.[13]

| Topology A: Equal weights analysis

|

Topology B: Implied weights analysis

|

See also

References

- ^ "Gondwana". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Molnar, R.E. (1980). "An ankylosaur (Ornithischia: Reptilia) from the Lower Cretaceous of southern Queensland". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 20: 65–75.

- ^ Lamanna, Matthew C.; Smith, Joshua B.; Attia, Yousry S.; Doson, Peter (2010). "From dinosaurs to dyrosaurids (Crocodyliformes): removal of the post-Cenomanian (Late Cretaceous) record of Ornithischia from Africa". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (3): 764–768. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2004)024[0764:FDTDCR]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 16525132.

- ^ Salgado, Leonardo (2013). "Considerations on the bony plates assigned to titanosaurs (Dinosauria, Sauropoda)". Ameghiniana. 40 (3): 441–456.

- ^ Arbour, Victoria M.; Currie, Philip J. (2015). "Systematics, phylogeny and palaeobiogeography of the ankylosaurid dinosaurs". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 14 (5): 1. doi:10.1080/14772019.2015.1059985. S2CID 214625754.

- ^ a b c d Soto-Acuña, Sergio; Vargas, Alexander O.; Kaluza, Jonatan; Leppe, Marcelo A.; Botelho, Joao F.; Palma-Liberona, José; Simon-Gutstein, Carolina; Fernández, Roy A.; Ortiz, Héctor; Milla, Verónica; et al. (2021). "Bizarre tail weaponry in a transitional ankylosaur from subantarctic Chile" (PDF). Nature. 600 (7888): 259–263. Bibcode:2021Natur.600..259S. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04147-1. PMID 34853468. S2CID 244799975.

- ^ a b Riguetti, Facundo; Pereda-Suberbiola, Xabier; Ponce, Denis; Salgado, Leonardo; Apesteguía, Sebastián; Rozadilla, Sebastián; Arbour, Victoria (2022-12-31). "A new small-bodied ankylosaurian dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of North Patagonia (Río Negro Province, Argentina)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 20 (1) 2137441. Bibcode:2022JSPal..2037441R. doi:10.1080/14772019.2022.2137441. ISSN 1477-2019. S2CID 254212751.

- ^ Agnolín, Federico L.; Álvarez Herrera, Gerardo; Rolando, Mauro Aranciaga; Motta, Matías; Rozadilla, Sebastián; Verdiquio, Lucía; D'Angelo, Julia S.; Moyano-Paz, Damián; Varela, Augusto N.; Sterli, Juliana; Bogan, Sergio; Miner, Santiago; Moreno Rodríguez, Ana; Muñoz, Gonzalo; Isasi, Marcelo P.; Novas, Fernando E. (2024). "Fossil vertebrates from the Cerro Fortaleza Formation (Upper Cretaceous), Santa Cruz Province, Argentina". Cretaceous Research. 154 105735. Bibcode:2024CrRes.15405735A. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2023.105735.

- ^ a b Soto Acuña, Sergio; Vargas, Alexander O.; Kaluza, Jonatan (2024). "A new look at the first dinosaur discovered in Antarctica: reappraisal of Antarctopelta oliveroi (Ankylosauria: Parankylosauria)". Advances in Polar Science. 35 (1): 78–107. doi:10.12429/j.advps.2023.0036.

- ^ a b Fonseca, A.O.; Reid, I.J.; Venner, A.; Duncan, R.J.; Garcia, M.S.; Müller, R.T. (2024). "A comprehensive phylogenetic analysis on early ornithischian evolution". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 22 (1) 2346577. Bibcode:2024JSPal..2246577F. doi:10.1080/14772019.2024.2346577.

- ^ Raven, T. J.; Barrett, P. M.; Joyce, C. B.; Maidment, S. C. R. (2023). "The phylogenetic relationships and evolutionary history of the armoured dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Thyreophora)" (PDF). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 21 (1). 2205433. Bibcode:2023JSPal..2105433R. doi:10.1080/14772019.2023.2205433.

- ^ Maidment, Susannah C. R.; Ouarhache, Driss; Ech-charay, Kawtar; Oussou, Ahmed; Boumir, Khadija; El Khanchoufi, Abdessalam; Park, Alison; Meade, Luke E.; Woodruff, D. Cary; Wills, Simon; Smith, Mike; Barrett, Paul M.; Butler, Richard J. (2025-08-27). "Extreme armour in the world's oldest ankylosaur". Nature: 1–6. doi:10.1038/s41586-025-09453-6. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ Agnolín, Federico L.; Rozadilla, Sebastián; Marsà, Jordi García; Álvarez Nogueira, Rodrigo; Miner, Santiago; Álvarez-Herrera, Gerardo; Novas, Fernando E.; Pol, Diego (January 13, 2026). "New remains of the armored dinosaur Patagopelta cristata Riguetti et al. 2022 (Ornithischia, Parankylosauria) from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina". Historical Biology: 1–64. doi:10.1080/08912963.2025.2583504. ISSN 0891-2963.