Nile

| Nile River | |

|---|---|

The Nile downstream from Murchison Falls | |

| Location | |

| Countries | Burundi, DR Congo, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda[1] |

| Major cities | Bahir Dar, Cairo, Khartoum, Jinja, Juba |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Rukarara River, Rwanda[2][a] |

| • coordinates | 02°19′35″S 29°21′30″E / 2.32639°S 29.35833°E[2] |

| • elevation | 2,539 m (8,330 ft)[2] |

| Length | 7,088 km (4,404 mi)[3] |

| Basin size | 2,927,843 km2 (1,130,447 mi2)[1] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Nile Delta into Mediterranean Sea |

| • average | 150 m3/s (5,300 cu ft/s)[4] |

The Nile[b] (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa and flows into the Mediterranean Sea. At 7,088 km (4,404 mi) long, it is the longest river in the world, although the volume of water it carries is much smaller than other major rivers such as the Amazon or Congo. Its drainage basin covers eleven countries: the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania, Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda, Kenya, Ethiopia, Eritrea, South Sudan, Sudan, and Egypt. It plays an important economic role in the economy of these nations, and it is the primary water source for South Sudan, Sudan and Egypt.

The Nile has two major tributaries: the White Nile and the Blue Nile. The White Nile, being the longer, is traditionally considered to be the headwaters, while the Blue Nile actually contributes 80% of the water and silt below the confluence of the two. The White Nile begins at Lake Victoria and flows through Uganda and South Sudan, while the Blue Nile begins at Lake Tana in Ethiopia[7] and flows into Sudan from the southeast. The two rivers meet at the Sudanese capital of Khartoum.

After Khartoum the river flows north, almost entirely through the Nubian Desert, to Cairo and its large delta, joining the Mediterranean Sea at Alexandria. Egyptian civilization and Sudanese kingdoms have depended on the river and its annual flooding since ancient times. Most of the population and cities of Egypt lie along those parts of the Nile valley north of the Aswan Dam. Nearly all the cultural and historical sites of Ancient Egypt developed and are found along river banks. The Nile is, with the Rhône and Po, one of the three Mediterranean rivers with the largest water discharge.

Etymology

The word Nile is derived from the from the Latin Nilus and the Ancient Greek Νεῖλος (Neilos), which probably originated from the Semitic term naḥal, meaning "river".[8] In the ancient Egyptian language, the Nile was called Ar or Aur, meaning "black".[8] In Coptic, it was called ⲫⲓⲁⲣⲟ.[8]

Physical geography

Sources

The source of the Nile is a tributary of the Rukarara River, in Nyungwe National Park, Rwanda, at 2°19′35″S 29°21′30″E / 2.32639°S 29.35833°E, at an elevation of 2,539 meters.[2][a] The source is defined as the starting point of the longest year-round watercourse in the Nile's drainage basin.[3] From this source, the river runs 7,088 km to the river's mouth at the Mediterranean Sea.[3] The distance was determined from satellite imagery, and was measured along the centerline of the river.[3]

The highest sources of the Nile (based on elevation) are on the slopes of the Rwenzori Mountains in Uganda.[10][c] The legendary Mountains of the Moon, described by Ptolemy, have been associated with Rwenzori.[10]

The southernmost source of the Nile is in Burundi at one of the heads of the Ruvyironza River, which feeds into the Kagera River. A monumuent was erected there in 1937 by Burkhart Waldecker near the town of Rutovu, close to Mount Kikizi.[12][d]

Lake Victoria is sometimes informally described as the source of the Nile, partly because early European explorers claimed that the lake was the source; and partly because the lake's outflow river is the most upstream river called the "Nile" (rivers flowing into Lake Victoria, such as the Kagera River, do not have the word "Nile" in their names).[13] Some have suggested that the true source of the Nile is the rain clouds that are often found above Lake Victoria, because they supply five times more water to the lake than the lake's inflow rivers.[11]

The source of the Blue Nile tributary is near the town of Gish Abay, south of Lake Tana.[14][e]

Regions of the Nile Basin

The Nile Basin can be divided into seven regions; five of these regions encompass the longest course of the Nile River. Proceeding in a downstream sequence, these five regions are: the African Great Lakes, the Mountain Nile, the White Nile, the main Nile, and the Nile Delta. Two additional regions encompass major tributaries: the Blue Nile and the Atbarah River.[8]

The region Africa around its Great Lakes contains the source of the Nile river. The source is the Rukarara River within Rwanda's Nyungwe National Park,[3] and it leads to the Kagera River,[f] which drains into Lake Victoria.[8] Although it is a large lake – the second-largest freshwater lake in the world[g] – Lake Victoria is relatively shallow. The Nile river first assumes the name "Nile" where Lake Victoria empties on its north side: the course from there to Lake Albert is called the Victoria Nile.[8] A pair of waterfalls – Ripon Falls and Owen Falls – were located where the Nile exits Lake Victoria, but have both been submerged by the construction of the Nalubaale dam. After Bujagali Falls and Bujagali Power Station, the Victoria Nile empties into Lake Kyoga. After exiting Lake Kyoga, the river is joined by the River Kafu tributary, then passes over Murchison Falls and flows into Lake Albert. Unlike Lake Victoria, Lake Albert is a deep lake surrounded by mountains. The river exits Lake Albert on its north shore, where it is called the Albert Nile; this stretch of the river is relatively flat and broad, and suitable for navigation by steamboats.[8]

The second region of the Nile Basin, proceeding downstream, is the Mountain Nile (Arabic: Bahr al Jabal).[15] This region begins near the town of Nimule and extends to Lake No, and is entirely within South Sudan. After passing through Nimule, the river goes through the Fula Rapids and on to Juba – the capital city of South Sudan. After Juba, the Nile passes through the town of Bor, then enters the Sudd, a large swamp located in a flat plain. The slope of the ground in the Sudd is only 1:13,000, so the river slows down and widens. Lush vegetation, including sedges, papyrus, and common water hyacinth (an invasive species) clog the waterways and make navigation difficult. At the downstream edge of the Sudd swamp, the Nile is joined by the Bahr el Ghazal River (Arabic: "gazelle river") a tribuatary flowing from the west. This confluence happens in Lake No.[8]

Continuing downstream, the third region of the Nile Basin is the White Nile region.[h] About 140 km after Lake No, the swamps diminish near the city of Malakal, and the river enters a long, placid stretch extending to Khartoum, where it is joined by the Blue Nile near Khartoum, the capital of Sudan.[8]

The fourth region of the Nile Basin – the main Nile[i] – extends from Khartoum to Cairo, the capital of Egypt. Soon after leaving Khartoum, the river goes enters the Sabloka Nature Reserve[j] and goes through the sixth (and furthest upstream) of the renowned six cataracts of the Nile. The Atbarah River – a major tributary – joins the Nile, which then follows a large S-shape curve to the west. Four more cataracts are encountered in this large S-curve, which render the river unnavigable, although ships may travel between the cataracts. The river then enters a large reservoir, Lake Nasser.[k] This lake – the world's second largest man-made lake – was formed when the Aswan High Dam was built in Egypt, and inundates more than 480 km of the Nile river. A second dam, older and smaller, lies beneath the Aswan High Dam, near the location of the first Nile cataract (now submerged). From these dams, the Nile flows about 800 km through a limestone plateau, bordered by large amounts of irrigated farmland, until it reaches Cairo.[8]

The fifth, and final, region encompassing the Nile river is the Nile Delta, a large triangular river delta that extends from Cairo to the Mediterranean Sea.[8] The river splits into two major distributaries (channels) within the delta: the Rosetta branch and the Damietta branch. The soil in the delta, ranging from 15 to 22 meters thick, was built-up over millennia from silt carried by the river from far upstream, in the Ethiopian highlands.[8]

The final two regions of the Nile Basin are the Blue Nile basin and the Atbarah River basin,[8] both discussed in the section on Tributaries.

Tributaries

The longest course of the Nile, which includes the White Nile tributary, has several other tributaries that feed into it.

Blue Nile

The Blue Nile springs from hills in Ethiopia[14] where it originates as a stream named Abay near the town of Gish Abay: Gish in an Amharic word meaning 'source', and Abay is the name of the stream.[14][17] Gish Abay flows into Lake Tana, a large, shallow lake, which has a single outflow where it adopts the 'Blue Nile' name. The Blue Nile travels south, then north passing through South Sudan into Sudan, where it joins with the White Nile at Khartoum to form the main Nile.[17] Along its course, the Blue Nile generates electricity at several hydro power plants, including the Tisabay hydropower project at the Blue Nile Falls, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam near the border between Ethiopia and South Sudan, the Roseires Dam near town of Ad Damazin, and the Sennar Dam.[18] The size of the Blue Nile's drainage basin is over 306,000 square km.[19]

Atbarah River

The Atbarah River is a tributary of the Nile which arises in northern Ethiopia, and joins the Nile about 320 km north of Khartoum.[20] Its drainage basin covers over 204,000 square km.[19] The Atbarah has a heavy flow during and following the monsoon season in Ethiopia (summer and fall), but can dry up in the winter and spring. Despite the intermittent nature of the river, it provides more than 10% of the total annual flow of the Nile.[20] Dams on the Atbarah include the Khashm el-Girba Dam, the Upper Atbara and Setit Dam Complex, and the Tekezé Dam (on the Tekezé River tributary).[21]

Bahr el Ghazal and Sobat River

The Bahr al Ghazal and the Sobat River are two tributaries of the White Nile. The Bahr el Ghazal arrives from the west, joining the White Nile at Lake No. The drainage basin of the Bahr el Ghazal river is large – about 860,000 square km[22] – and receives a relatively large amount of rain, but its contribution to the Nile is insignificant.[l] The basin includes Lake Kundi and Lake Keilak. The Bahr el Ghazal passes through the city of Wau, South Sudan: it is a permanent stream east of Wau, but a seasonal stream to the west.[24]

Another tributary, the Sobat River, joins the White Nile (after the Bahr el Ghazal confluence, before the Blue Nile) near the town of Malaka. Its basin – which includes the Machar Marshes[25] – covers about 225,000 square km.[26] The Sobat floods between July and December.[8]

Hydrography

Nile River |

|---|

| Schematic diagram. Distances not to scale. Top = upstream/south; Bottom = downstream/north. [S3] are stations used in tables below.[27] |

Flow and floods

Although the Nile is the longest river in the world, it is far from having the largest discharge. Its flow – about 84 cubic km per year[m] – is small compared to other major rivers. The Nile's discharge is only 1% of the Amazon, 6% of the Congo, and 12% of the Yellow River.[28]

The present flow regime of the Nile was established about 15,000 years ago, when the summer monsoon shifted and substantially increased rainfall in the area of Lake Victoria and Lake Albert.[29]

The annual contributions to the main Nile from the three primary tributaries are: 54% from the Blue Nile, 32% from the White Nile (including contributions from the Bahr el Ghazal and Sobat tributaries), and 14% from the Atabarah.[30] The White Nile passes through the Sudd swamps before it reaches the Blue Nile; about half the water flowing into the Sudd is lost to evaporation before it flows out.[31] At the confluence of the Blue Nile and White Nile in Khartoum, the Blue Nile provides two thirds of the water.[32]

About 80% to 85% of the Nile's water reaching Egypt originates in Ethiopia (the Blue Nile, Atbarah, and Sobat tributaries combined); the remaining 15% to 20% is from the Great Lakes region and western South Sudan (the Mountain Nile and Bhar Ghazal tributaries).[33]

The highlands of the White Nile and Blue Nile both experience seasonal rain, but the White Nile's flow into the main Nile is much more constant than the Blue Nile.[8] This is due to the many lakes and wetlands on the White Nile, which moderate the threat of flooding.[34]

In contrast, the Blue Nile has tremendous variability in its flow: it floods between July and October, due to summer monsoon rains.[8] The waters of the Blue Nile are so substantial during the summer and autumn, that the White Nile backs-up during this time at the confluence.[35] During the summer floods, the contributions to the main Nile are about 70% from the Blue Nile, about 20% from the Atbarah, and about 10% from the White Nile.[8] At the peak of the flood, the daily flow into Lake Nasser is about 0.71 km3, about three times the annual daily average of 0.23 km3 per day.[36] The Blue Nile, although shorter than the White Nile, contributes more water to the main Nile.[37]

As the Blue Nile flow diminishes in the winter, the pent-up waters of the White Nile increase their flow past Khartoum.[35] In April and May, the White Nile supplies about 80% of the main Nile's water. Thus, the areas downstream of Khartoum receive a steady (not to say constant) flow that made irrigation possible year-round.[35]

Prior to the construction of dams on the Nile, the variability of flow in Egypt was significant: higher in the summer/fall; lower in the winter/spring. However, following the construction of the Aswan High Dam – which created a reservoir that can hold about two years of river flow – the flow downstream from that dam is now more constant year-round.[38][n]

Hydrology data

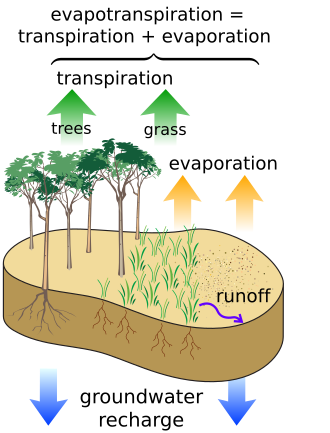

Scientists analyze water balance in the Nile basin with hyrdological principles. Within any river basin, the water inputs equal the water outputs. This balancing principle relies on measuring several aspects of water movement: precipitation (P), evaporation and transpiration (ET), groundwater recharge (), lake-filling (D), and stream runoff (Q). These values are related by the following water balance equation:

Basin data

The following tables summarize some of those water measurements for several basins within the Nile basin. The data is based on measurements made at twelve river measurement stations.[27][o] The stations divide the Nile basin into twelve smaller basins. These basins are each named after their downstream station. For example, the Murchison Falls station (2) is downstream of the Lake Victoria outlet station (1), so the basin between them is named the Murchison Falls basin.[40] The data includes the following:

- Per-basin data: land surface area, precipitation, evapotranspiration, surface runoff

- Per-station data: discharge

Most of the per-basin data is presented as annual measurements (usually in km3); but some data is also presented as an equivalent "depth" value (millimeters per year, covering the entire basin).[27] The discharge "rate" data is an average of the entire year.

The basin data in the table is for each individual basin; it is not cumulative. For example, the runoff of station 5 is the runoff for the basin between stations 4 and 5, and excludes runoffs from upstream basins (1,2,3).

The water balance datum of each basin shown in the following tables is a rudimentary calculation of precipitation−evapotranspiration.[41] Each basin is classified as a source, sink, or neutral, indicating if it is a net contributor to the river's flow (source) or if the adjusted evapotranspiration significantly exceeds precipitation (sink).[42]

The measuring stations are listed in the tables proceeding from upstream to downstream.

| Measuring Station |

Basin Area km2 |

Precip km3 (depth) |

Evap km3 (depth) |

Water Balance km3 |

Runoff km3 (depth) |

Discharge km3 (rate) |

Source? (No=sink) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Lake Victoria outlet[p] | 264,259 | 353 (1,337 mm) |

279 (1,055 mm) |

74 | 57 (214 mm) |

37 (1,176 m3/sec) |

Yes |

| 2 Murchison Falls[q] | 85,513 | 109 (1,276 mm) |

94 (1,105 mm) |

15 | 9 (102 mm) |

30 (946 m3/sec) |

Yes |

| 3 Mongalla[r] | 131,691 | 159 (1,209 mm) |

158 (1,201 mm) |

1 | 5 (38 mm) |

33 (1,050 m3/sec) |

Neutral |

| 4 Malakal[s] | 925,160 | 798 (863 mm) |

957 (1,034 mm) |

−159 | 150 (162 mm) |

30 (939 m3/sec) |

No |

| 5 Khartoum[t] | 257,130 | 134 (520 mm) |

174 (676 mm) |

105 | 14 (53 mm) |

28 (897 m3/sec) |

No |

| Measuring Station |

Basin Area km2 |

Precip km3 (depth) |

Evap km3 (depth) |

Water Balance km3 |

Runoff km3 (depth) |

Discharge km3 (rate) |

Source? (No=sink) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 Roseires Dam[44] | 188,296 | 246 (1,309 mm) |

142 (752 mm) |

105 | 70 (372 mm) |

49 (1,548 m3/sec) |

Yes |

| 7 Khartoum[u] | 118,651 | 96 (686 mm) |

72 (605 mm) |

10 | 9 (75 mm) |

48 (1,513 m3/sec) |

Neutral |

| Measuring Station |

Basin Area km2 |

Precip km3 (depth) |

Evap km3 (depth) |

Water Balance km3 |

Runoff km3 (depth) |

Discharge km3 (rate) |

Source? (No=sink) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 Khashm el Girba[v] | 100,318 | 95 (951 mm) |

66 (656 mm) |

30 | 10 (104 mm) |

10 (302 m3/sec) |

Yes |

| 9 Mouth of Atbarah River[w] | 104,051 | 22 (215 mm) |

25 (242 mm) |

−3 | 1 (6 mm) |

12 (373 m3/sec) |

Neutral |

| Measuring Station |

Basin Area km2 |

Precip km3 (depth) |

Evap km3 (depth) |

Water Balance km3 |

Runoff km3 (depth) |

Discharge km3 (rate) |

Source? (No=sink) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 Dongola[44] | 390,180 | 34 (87 mm) |

45 (116 mm) |

−11 | 0 (0 mm) |

83 (2,622 m3/sec) |

Neutral |

| 11 Aswan dam[44] | 188,011 | 2 (12 mm) |

13 (70 mm) |

−10 | 0 (0 mm) |

87 (2,757 m3/sec) |

No |

| 12 Cairo/Delta[x] | 145,293 | 3 (18 mm) |

12 (85 mm) |

−10 | 0 (0 mm) |

40 (1,251 m3/sec) |

No |

Country data

This table contains hydrology data for the Nile Basin, on a per-country basis. Portions of countries outside the Nile Basin are excluded from the values.

| Country | Basin Area km2[y] |

Precip km3 (depth) |

Evap km3 (depth) |

Water Balance km3 |

Runoff km3 (depth) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burundi | 13,240 | 14 (1,092 mm) |

13 (951 mm) |

2 | 3 (242mm) |

| DR Congo | 19,919 | 96 (686 mm) |

72 (605 mm) |

10 | 9 (75 mm) |

| Egypt | 235,108 | 4 (1,092 mm) |

13 (951 mm) |

39 | 0 (0mm) |

| Eritrea | 24,427 | 14 ( 572 mm) |

12 (507 mm) |

2 | 0 (16 mm) |

| Ethiopia | 363,775 | 459 ( 1,262 mm) |

295 (812 mm) |

164 | 138 (380 mm) |

| Kenya | 49,513 | 21 (1,532 mm) |

49 (987 mm) |

1 | 23 (465 mm) |

| Rwanda | 20,676 | 76 ( 993 mm) |

20 (966 mm) |

27 | 4 (180mm) |

| South Sudan | 617,256 | 612 ( 991 mm) |

757 (1,227 mm) |

−146 | 92 (150 mm) |

| Sudan | 1,226,660 | 364 ( 297 mm) |

445 (363 mm) |

−81 | 23 (19 mm) |

| Tanzania | 120,506 | 160 (1,327 mm) |

122 (1,014 mm) |

38 | 18 (150 mm) |

| Uganda | 236,763 | 301 (1,271 mm) |

276 (1,165 mm) |

25 | 22 (91mm)

|

| Total (depths are means) |

2,927,843 | 2,048 (699 mm) |

2,056 (702 mm) |

−8 | 324 (111 mm) |

Sediment transport

The Nile carries sediment downstream. The movement of sediment is classified as suspended sediment (particles suspended in the water) or bedload (sediment on the river bottom that rolls or tumbles downstream).

Ninety-six percent of the transported sediment carried by the Nile[46] comes from the Atbarah and Blue Nile, both of which originate in Ethiopia, with fifty-nine percent of the water coming from the Blue Nile. The erosion and transportation of silt only occurs during the Ethiopian rainy season when rainfall is especially high in the Ethiopian Highlands; the rest of the year, the great rivers draining Ethiopia into the Nile have a weaker flow. In harsh and arid seasons and droughts, the Blue Nile dries out completely.[47]

Sediment carried by the Nile, or its tributaries, into a reservoir has the potential to settle in the reservoir and reduce the storage capacity of the reservoir. Sediment accumulated behind the Sennar Dam, Roseires Dam (on the Blue Nile), and Khashm el Girba Dam (on the Atbarah) has significantly reduced the storage capacity of their reservoirs since they were built.[48]

Annual sediment transport measured at several locations are listed in the following table.[49] These measurements conducted at various dates, ranging from 1997 to 2019. The bedload percentages are the ratio of bedload sediment to total (bedload and suspended) sediment. These data were collected before the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, which has a significant impact on sediment loads downstream of the dam.[49]

- Gilgel Abay, Ethiopia : 7.6 million tonnes of suspended, and an additional 0.7% of bedload

- El Deim (at the border of Ethiopia and Sudan): 140 million tonnes[48]

- Aswan, Egypt: 0.14 million tonnes of suspended, and an additional 28% of bedload

- Beni Sweif, Egypt: 0.5 million tonnes of suspended, and an additional 20% of bedload

- Qena, Egypt: 0.27 million tonnes of suspended, and an additional 27% of bedload

- Sohag, Egypt: 1.5 million tonnes of suspended, and an additional 13% of bedload

Nilometers

Measurements of the Nile's flow has always been essential to help Egyptians manage their safety and irrigation. Simple gauges, called nilometers, have been used to measure the level of the Nile for thousands of years.[50] An important nilometer has been in use on Roda Island since at least 622 AD; Egyptians kept records of maximum and minimum river levels from that gauge until 1921.[50] Modern gauges to measure the river level began to be installed in the 1860s, and gauges that measured the river's current – which provide more accurate flow information – were installed around 1900.[50]

Geological history

Eonile in the Cenozoic era

During the Cenozoic era, the water drainage in northeast Africa (roughly where modern Egypt is) went through three major phases. First, in the late Eocene, the Gilf system drained to the west, then north, and then into the Tethys Sea.[51] This was followed, in the early Miocene, by the Qena system, in which several fragmentary rivers were formed near the Red Sea, generally flowing to the south.[51] Finally, the Eonile river was formed in the late Miocene (8 to 6 MYA), which connected the Qena segments into a single river. The Eonile reversed the flow of the Qena, and flowed north into the Mediterranean Sea.[51]

During the late-Miocene Messinian salinity crisis, when the Mediterranean Sea was a closed basin and evaporated to the point of being empty or nearly so, the Nile cut its course down to the new base level until it was several hundred meters below world ocean level at Aswan and 2,400 m (7,900 ft) below Cairo.[52][53] This created a very long and deep canyon which was filled with sediment after the Mediterranean was recreated.[54] At some point the sediments raised the riverbed sufficiently for the river to overflow westward into a depression to create Lake Moeris.[citation needed]

Lake Tanganyika drained northwards into the Nile until the Virunga Volcanoes blocked its course in Rwanda. The Nile was much longer at that time, with its furthest headwaters in northern Zambia.[citation needed]

The predecessor to the modern Nile first flowed through Egypt approximately on its modern course during the early part of the Würm glaciation period.[55]

Since 2 million years ago

After the Eonile was formed about 6 million years ago (MYA), it subsequently evolved through several phases before the modern Nile was formed:[56]

- Paleo-Nile, formed about 1.7 MYA

- Proto-Nile, formed about 1.5 MYA

- Pre-Nile, formed about 700 KYA (KYA = thousand years ago)

- Neo-Nile, formed about 120 KYA

- Modern Nile, formed about 30,000 years ago, when the African Great Lakes region tilted northward, and began draining into the Nile.[57]

Integrated Nile

There are two theories about the age of the integrated Nile. One is that the integrated drainage of the Nile is of young age and that the Nile basin was formerly broken into series of separate basins, only the most northerly of which fed a river following the present course of the Nile in Egypt and Sudan. Rushdi Said postulates that Egypt supplied most of the waters of the Nile during the early part of its history.[58]

The other theory is that the drainage from Ethiopia via rivers equivalent to the Blue Nile, the Atbara and the Takazze flowed to the Mediterranean via the Egyptian Nile since well back into Tertiary times.[59]

R. B. Salama suggests that a series of separate closed continental basins each occupied one of the major parts of the Sudanese Rift System that during the Paleogene and Neogene periods (66 million to 2.588 million years ago): Mellut rift, White Nile rift, Blue Nile rift, Atbara rift and Sag El Naam rift.[60]

Human history

Ancient Egyptian civilization

The Greek historian Herodotus wrote that "Egypt was the gift of the Nile". An unending source of sustenance, it played a crucial role in the development of Egyptian civilization. Because the river overflowed its banks annually and deposited new layers of silt, the surrounding land was very fertile. The Ancient Egyptians cultivated and traded wheat, flax, papyrus and other crops around the Nile. Wheat was a crucial crop in the famine-plagued Middle East. This trading system secured Egypt's diplomatic relationships with other countries and contributed to economic stability. Far-reaching trade has been carried on along the Nile since ancient times.[citation needed] A tune, Hymn to the Nile, was created and sung by the ancient Egyptian peoples about the flooding of the Nile River and all of the miracles it brought to Ancient Egyptian civilization.[61]

As the Nile was such an important factor in Egyptian life, the ancient calendar was even based on the three cycles of the Nile.[citation needed] These seasons, each consisting of four months of thirty days each, were called Akhet, Peret, and Shemu. Akhet, which means inundation, was the time of the year when the Nile flooded, leaving several layers of fertile soil behind, aiding in agricultural growth.[62] Peret was the growing season, and Shemu, the last season, was the harvest season when there were no rains.[62]

European exploration

To the ancient Greeks and Romans, the upper reaches of the White Nile remained largely unknown, as they failed to penetrate the Sudd wetlands of South Sudan. Vitruvius thought that source of the Nile was in Mauritania, on the "other" (south) side of the Atlas Mountains.[65] Various expeditions failed to determine the river's source. Agatharchides records that in the time of Ptolemy II Philadelphus, a military expedition had penetrated far enough along the course of the Blue Nile to determine that the summer floods were caused by heavy seasonal rainstorms in the Ethiopian Highlands, but no European of antiquity is known to have reached Lake Tana. The Tabula Rogeriana depicted the source as three lakes in 1154.[citation needed]

Europeans began to learn about the origins of the Nile in the 14th century when the Pope sent monks as emissaries to Mongolia who passed India, the Middle East and Africa, and described being told of the source of the Nile in Abyssinia (Ethiopia).[66] Later in the 15th and 16th centuries, travelers to Ethiopia visited Lake Tana and the source of the Blue Nile in the mountains south of the lake. Supposedly, Paolo Trevisani (c. 1452–1483), a Venetian traveller in Ethiopia, wrote a journal of his travels to the origin of the Nile that has since been lost.[67][68] James Bruce claimed to be the first European to have visited the headwaters.[69] Modern writers give the credit to the Jesuit Pedro Páez. Páez's account of the source of the Nile[70] is a long and vivid account of Ethiopia. It was published in full only in the early 20th century, but was featured in works of Páez's contemporaries, like Baltazar Téllez,[71] Athanasius Kircher[72] and Johann Michael Vansleb.[73]

Europeans had been resident in Ethiopia since the late 15th century and one of them may have visited the headwaters even earlier without leaving a written trace. The Portuguese João Bermudes published the first description of the Tis Issat Falls in his 1565 memoirs, compared them to the Nile Falls alluded to in Cicero's De Republica.[74] Jerónimo Lobo describes the source of the Blue Nile, visiting shortly after Pedro Páez. Telles also uses his account.[citation needed]

The White Nile was even less understood. The ancients mistakenly believed that the Niger River represented the upper reaches of the White Nile. For example, Pliny the Elder writes that the Nile had its origins "in a mountain of lower Mauretania", flowed above ground for "many days" distance, then went underground, reappeared as a large lake in the territories of the Masaesyli, then sank again below the desert to flow underground "for a distance of 20 days' journey till it reaches the nearest Ethiopians."[75]

Modern exploration of the Nile basin began with the conquest of the northern and central Sudan by the Ottoman viceroy of Egypt, Muhammad Ali, and his sons from 1821 onward.[citation needed] As a result of this, the Blue Nile was known as far as its exit from the Ethiopian foothills and the White Nile as far as the mouth of the Sobat River. Three expeditions under a Turkish officer, Selim Bimbashi, were made between 1839 and 1842, and two got to the point about 30 kilometres (20 miles) beyond the present port of Juba, where the country rises and rapids make navigation very difficult.[citation needed]

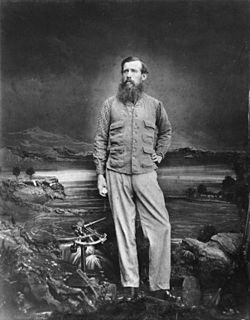

Lake Victoria was first sighted by Europeans in 1858 when British explorer John Hanning Speke reached its southern shore while traveling with Richard Francis Burton to explore central Africa and locate the great lakes.[citation needed] Believing he had found the source of the Nile on seeing this "vast expanse of open water" for the first time, Speke named the lake after Queen Victoria. Burton, recovering from illness and resting further south on the shores of Lake Tanganyika, was outraged that Speke claimed to have proven his discovery to be the true source of the Nile when Burton regarded this as still unsettled. A quarrel ensued which sparked intense debate within the scientific community and interest by other explorers keen to either confirm or refute Speke's discovery. British explorer and missionary David Livingstone pushed too far west and entered the Congo River system instead. It was ultimately Welsh-American explorer Henry Morton Stanley who confirmed Speke's discovery, circumnavigating Lake Victoria and reporting the great outflow at Ripon Falls on the lake's northern shore.[citation needed]

Economy

The Nile has long been used to transport goods along its length. Winter winds blow south, up river, so ships could sail up river using sails and down river using the flow of the river. While most Egyptians still live in the Nile valley, the 1970 completion of the Aswan Dam ended the summer floods and their renewal of the fertile soil, fundamentally changing farming practices. The Nile supports much of the population living along its banks, enabling Egyptians to live in otherwise inhospitable regions of the Sahara. The river's flow is disturbed at several points by the Cataracts of the Nile which form an obstacle to navigation by boats. The Sudd also forms a formidable navigation obstacle and impedes water flow, to the extent that Sudan had once attempted to build the Jonglei Canal to bypass the swamp.[76][77]

Nile cities include Khartoum, Aswan, Luxor (Thebes), and the Giza – Cairo conurbation.[citation needed] The first cataract, the closest to the mouth of the river, is at Aswan, north of the Aswan Dam. This part of the river is a regular tourist route, with cruise ships and traditional wooden sailing boats known as feluccas. Many cruise ships ply the route between Luxor and Aswan, stopping at Edfu and Kom Ombo along the way. Security concerns have limited cruising on the northernmost portion for many years.[citation needed]

Despite the development of many reservoirs, drought during the 1980s led to widespread starvation in Ethiopia and Sudan, but Egypt was nourished by water impounded in Lake Nasser. Drought has proven to be a major cause of fatality in the Nile river basin. According to a report by the Strategic Foresight Group, droughts in the last century have affected around 170 million people and killed half a million people.[78] From the 70 incidents of drought which took place between 1900 and 2012, 55 incidents took place in Ethiopia, Sudan, South Sudan, Kenya and Tanzania.[78]

Water politics

Colonial era

Post-colonial era

The Nile waters have affected the populations, cultures, economies, and politics of Northeast Africa and the Nile Basin for many decades. The most recent water sharing dispute is the dispute between Egypt and Ethiopia over the $4.5 billion Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, which has become a national preoccupation in both countries, stoking patriotism, deep-seated fears and even murmurs of war.[79] In both Egypt and Ethiopia the Nile and the Grand Ethiopian Renaisance Dam are parts of the national identity. In Ethiopia it is seen as a path towards increased development, whereas in Egypt fears of drought and water shortage prevail.[80] For Egypt, to justify its excessive access to Nile waters, three treaties signed in 1902, 1929, and 1959 are used, which are however criticized. The 1902 and 1929 treaties were heavily influenced by colonialism as the British Empire made African colonies make concessions on Nile waters to the benefit of British Egypt. With the end of colonialism and the emergence of postcolonialism, these treaties are seen as colonial products, which have lost their validity.[81] The distribution of Nile waters in the treaties also sets the foundation for the alliance of Sudan and Egypt in the Nile Basin. Both states distributed practically all Nile waters between them in the 1959 agreement and still align their politics regarding the Nile waters.[82][83] After the announcement of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, Sudan and Egypt conducted three military exercises together.[84][85]

Already before the plans for the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam were published in 2014, several attempts have been made to establish new agreements between the countries sharing the Nile waters. Countries including Uganda, Sudan, Ethiopia and Kenya have complained about Egyptian domination of its water resources and the 1999 Nile Basin Initiative promoted a peaceful cooperation among those states.[86][87] On 14 May 2010 at Entebbe, Uganda, Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Tanzania signed a new agreement on sharing the Nile waters even though this agreement raised strong opposition from Egypt and Sudan. Ideally, such international agreements should promote equitable and efficient usage of the Nile basin's water resources. Without a better understanding about the availability of the future water resources of the Nile, it is possible that conflicts could arise between these countries relying on the Nile for their water supply, economic and social developments.[88] The conflicting priorities of the Nile riparian countries according to different domestic factors such as socioeconomic status, level of development, or climatic conditions severely affect the stance of Egypt and Ethiopia in negotiations.[89] In the several rounds of negotiations since 2014 especially the filling and operation of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam in times of water scarcity appeared to be a critical topic where no consensus was found.[89] The talks about the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam are almost exclusively between Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia, however some rounds of negotiations were accompanied and led by other actors such as the United States, the African Union, or the European Union.[90] The failure of the several rounds of negotiations has led some to argue that the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam dispute might develop into a water war. Especially after the failed negotiations led by the United States, this risk was discussed as president Trump threatened that Egypt might "blow up the dam".[91][92] Nevertheless, a water war is thus far considered unlikely, given the serious consequences this would have for the countries involved and the region.[93] Also, given the high protection of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam it is unclear if the Egyptian military would be successful in an attack.[94]

Ecology

Plants

Plants common in the Sudd swamp include species that thrive in deep flooding (such as Vossia, Echinochloa stagnina, and Cyperus papyrus) as well as species that thrive in shallow flooding (such as Oryza, Echinochloa pyramidalis, and Phragmites).[95]

Animals

Conservation

Pollution

Sources of pollution in the Nile include agricultural, industrial, and household waste. There are 36 industries that discharge their pollution sources directly into the Nile, and 41 into irrigation canals. These types of industries are: chemical, electrical, engineering, fertilizers, food, metal, mining, oil and soap, pulp and paper, refractory, textile and wood. There are over 90 agricultural drains that discharge into the Nile that also include industrial wastewater.[96]

Pollution sources in the Nile between Aswan and the delta include human activities, agricultural runoff, and industrial waste. Concentrations of pollutants increase as the river flows downstream, due to the cumulative effects of pollution sources.[97] The Nile delta has relatively high levels of heavy metal concentrations. The delta is susceptible to accumulated concentrations because of poor flushing actions, exacerbated by a flat topography and heavy silting in the riverbed.[98] The northeast region of the delta is the most polluted part of the river in Egypt, and has a high incidence of pancreatic cancer, which may be related to high levels of heavy metals and organchlorine pesticides found in the soil and water.[99]

Climate change

In culture

Art

Myth and religion

References

Footnotes

- ^ a b The source location was initially determined in 1969 by a group of researchers from Waseda University. In 2006, a group of adventurers rediscovered this source, and placed a large marker on a nearby tree. In 2009, academics used satellite imagery to further refine the location of the source, placing it at a nearby spring, several km from the 1969/2006 source.[2]

- ^

- ^ Some have described these high sources as the "true source" of the Nile.[11]

- ^ This southernmost source is at 3°54′54″S 29°50′16″E / 3.914926960316476°S 29.83791290756115°E[12]

- ^ The source of the Blue Nile is about 75 km south of Lake Tana, at 10°58′12″N 37°11′55″E / 10.9699262917°N 37.198626789087°E.[14]

- ^ The Rukarara River leads to the Mwogo River, which leads to the Nyabarongo River, which leads to the Kagera River, which drains into Lake Victoria.

- ^ Measured by area, not volume.

- ^ The White Nile River – distinguished from the White Nile region – is the portion of the Nile that extends from Lake Victoria to Khartoum.

- ^ The segment of the Nile river between the Blue/White confluence and the Mediterranean is called the main Nile or the Sharan Nile.[16]

- ^ Also transliterated as Sablūkah or Sababka.

- ^ Lake Nasser is called 'Lake Nubia' in Sudan.

- ^ Most precipitation in the Bahr el Ghazal basin is lost to evaporation before reaching the Nile.[23]

- ^ Measured at Aswan.[28]

- ^ The annual flow of the river at Aswan is about 84 cubic km; and the capacity of the Aswan High Dam's reservoir is about 160 cubic km.[39]

- ^ The names of some stations with obscure or confusing names are presented here with names of nearby major geographic features. For example, the Kilo3 source is presented here as "Mouth of the Atbarah River". The Paara source is presented here as "Murchison Falls". The "Owen Reservoir" is presented here as "Lake Victoria outlet".

- ^ Measured at Nalubaale dam.[44]

- ^ Measured at Paara (Uganda), slightly downstream from Murchison Falls.[44]

- ^ Measured at Mongalla, South Sudan, about 40 km downstream (north) of Juba.[44]

- ^ Malakal is after the confluence of the White Nile and Sobat. It includes both Bahr el Ghazal and Sobat River tributaries.[44]

- ^ Measured at Al Mogran before the Blue Nile confluence (includes only the White Nile).[44]

- ^ Includes only Blue Nile (excludes White Nile).[44]

- ^ Roughly at the midpoint of the Atbarah river.[44]

- ^ Measured at the Kilo3 station, where the Atbarah joins the Nile.[44]

- ^ Station is El Ekhsase, near Cairo. Basin data includes the Nile Delta, even though the delta is downstream of the station.[45]

- ^ Basin area is the Nile basin within the country.

Citations

- ^ a b c Senay 2014, Table 5.

- ^ a b c d e

- Liu 2009.

- Tvedt 2021, p. 278.

- ^ a b c d e Liu 2009.

- ^ "Water Accounting in the Nile River Basin". United Nations.

- ^ "ⲓⲁⲣⲟ". Wiktionary. Archived from the original on 14 July 2023. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ Reinisch, Leo (1879). Die Nuba-Sprache. Grammatik und Texte. Nubisch-Deutsches und Deutsch-Nubisches Wörterbuch Erster Theil. Zweiter Theil. p. 220.

- ^ The river's outflow from that lake occurs at 12°02′09″N 37°15′53″E / 12.03583°N 37.26472°E

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Hurst 2025.

- ^ "The Nile River". Nile Basin Initiative. 2011. Archived from the original on 2 September 2010. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ a b

- Eggermont 2009, pp. 243–246.

- Tvedt 2021, p. 282.

- ^ a b Sutcliffe 2009, pp. 340–341.

- ^ a b Tvedt 2021, pp. 300–301.

- ^ Tvedt 2021, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d Tvedt 2021, pp. 323–324.

- ^

- Hurst 2025.

- Tvedt 2021, p. 5. Arabic translation.

- ^

- Sutcliffe 2009, p. 360.

- Williams 2009, p. 62.

- ^ a b McKenna 2025.

- ^

- Tvedt 2021, pp. 274, 339. Blue Nile Falls.

- Tvedt 2021, pp. 116, 135. Roseires Dam.

- Tvedt 2021, p. 341. Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.

- Tvedt 2021, pp. 118, 131, 348. Sennar Dam.

- ^ a b Senay 2014, Table 3.

- ^ a b

- Hurst 2025.

- Dumont 2009, p. 7.

- Sutcliffe 2009, p. 339.

- ^

- Tvedt 2021, pp. 321, 336–337. Tekezé Dam.

- Sutcliffe 2009, p. 359. Khashm el-Girba Dam.

- Hafez 2024. Upper Atbara and Setit Dam Complex.

- ^ "Baḥr al-Ghazāl" Britannica.

- ^ Sutcliffe 2009, p. 352-354.

- ^

- Sutcliffe 2009, p. 352-354.

- Dumont 2009, p. 6.

- ^ Dumont 2009, p. 6.

- ^ Shahin 2002, p. 276.

- ^ a b c Senay 2014.

- ^ a b Tvedt 2021, p. 4.

- ^ Williams 2009, pp. 61, 70.

- ^ Senay 2014, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5. Based on annual discharge figures: Blue Nile 48 km3; White Nile 28 km3; Atbarah 12 km3.

- ^ Sutcliffe 2009, p. 346.

- ^ Sutcliffe 2009, p. 339.

- ^ Okidi 1994, pp. 321, 325, 330, 341.

- ^ Sutcliffe 2009, p. 357.

- ^ a b c Tvedt 2021, p. 5.

- ^

- Hurst 2025. Summer flood: 25.1 billion ft3 per day, or 0.71 km3 per day.

- Senay 2014, Table 4. Annual mean measured at Dongola station: 83 km3 per year, or 0.23 km3 per day.

- ^ Sutcliffe 2009, pp. 339, 356.

- ^

- El-Shabrawy & Dumont 2009, p. 125.

- Tvedt 2021, p. 5.

- ^ El-Shabrawy & Dumont 2009, p. 125.

- ^ Senay 2014, Sec. 2.2.

- ^ Senay 2014, Sec. 2.2.5, 2.2.6.

- ^ Senay 2014, Sec. 3.5.5, Table 6.

- ^ a b c d Senay 2014, Table 3, Table 4, Table 6, Sec 3.5.5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Senay 2014, Figure 1, Table 2.

- ^ Senay 2014, Figure 1, Table 2, Sec 2.2.5.

- ^ Marshall et al.,"Late Pleistocene and Holocene environmental and climatic change from Lake Tana, source of the Blue Nile" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2006. Retrieved 30 September 2006.

- ^ "Two Niles Meet: Image of the Day". earthobservatory.nasa.gov. 26 April 2013. Archived from the original on 15 April 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ a b Sutcliffe 2009, p. 359.

- ^ a b Lemma 2019, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d Sutcliffe 2009, pp. 340, 361.

- ^ a b c Hamza 2009, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Warren, John (2006). Evaporites: Sediments, Resources and Hydrocarbons. Berlin: Springer. p. 352. ISBN 3-540-26011-0.

- ^ El Mahmoudi, A.; Gabr, A. (2008). "Geophysical surveys to investigate the relation between the Quaternary Nile channels and the Messinian Nile canyon at East Nile Delta, Egypt". Arabian Journal of Geosciences. 2 (1): 53–67. doi:10.1007/s12517-008-0018-9. ISSN 1866-7511. S2CID 128432827.

- ^ Embabi, N.S. (2018). "Remarkable Events in the Life of the River Nile". Landscapes and Landforms of Egypt. World Geomorphological Landscapes. pp. 39–45. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-65661-8_4. ISBN 978-3-319-65659-5. ISSN 1866-7538. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ Said 1981, p. 4.

- ^

- Said 1981, pp. 12–13, 17, 24, 40, 46, 51, 61.

- Van Damme & Bocxlaer 2009, p. 606.

- ^ Van Damme & Bocxlaer 2009, p. 606.

- ^ Said 1981.

- ^ Williams, M.A.J.; Williams, F. (1980). Evolution of Nile Basin. In M.A.J. Williams and H. Faure (eds). The Sahara and the Nile. Balkema, Rotterdam, pp. 207–224.

- ^ Salama, R.B. (1987). "The evolution of the River Nile, The buried saline rift lakes in Sudan". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 6 (6): 899–913. doi:10.1016/0899-5362(87)90049-2.

- ^ Halsall, Paul (May 1998). "Hymn To The Nile". Fordham University. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ a b Springer, Lisa; Neil Morris (2010). Art and Culture of Ancient Egypt. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-4358-3589-4.

- ^ Garstin & Cana 1911, p. 698.

- ^ Garstin & Cana 1911, p. 693.

- ^ Vitruvius, de Architectura, VII.2.7.

- ^ Yule, Henry. Sir Henry Yule, Cathay and the way thither: being a collection of medieval notices of China Vol. II (1913–16). London: Hakluyt Society. pp. 209–269. Archived from the original on 22 January 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ Dizionario biografico universale, Volume 5, by Felice Scifoni, Publisher Davide Passagli, Florence (1849); page 411.

- ^ Ten Centuries of European Progress Archived 30 May 2023 at the Wayback Machine by Lowis D'Aguilar Jalkson (1893) pages 126–127.

- ^ Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile

- ^ History of Ethiopia, circa 1622

- ^ Historia geral da Ethiopia a Alta, 1660

- ^ Mundus Subterraneus, 1664

- ^ The Present State of Egypt, 1678.

- ^ S. Whiteway, editor and translator, The Portuguese Expedition to Abyssinia in 1441–1543, 1902. (Nendeln, Liechtenstein: Kraus Reprint, 1967), p. 241. Referring to Cicero, De Republica, 6.19 Archived 2 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Natural History, 5.(10).51

- ^ Shahin 2002, pp. 286–287.

- ^ "Big Canal To Change Course of Nile River" Archived 5 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine. October 1933. Popular Science (short article on top-right of page with map).

- ^ a b Blue Peace for the Nile, 2009 Archived 8 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine; Report by Strategic Foresight Group

- ^ Walsh, Decian (9 February 2020). "For Thousands of Years, Egypt Controlled the Nile. A New Dam Threatens That". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 February 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ Yihdego, Zeray (25 May 2017). "The Fairness 'Dilemma' in Sharing the Nile Waters: What Lessons from the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam for International Law?". Brill Research Perspectives in International Water Law. 2 (2): 2–3. doi:10.1163/23529369-12340006. hdl:2164/12347. ISSN 2352-9350.

- ^ Milas, Seifulaziz Leo (2013). Sharing the Nile: Egypt, Ethiopia and the geo-politics of water. London: Pluto Press. pp. 65–68, 72–73. ISBN 978-1-84964-813-4.

- ^ Ranjan, Amit (2 January 2024). "Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam dispute: implications, negotiations, and mediations". Journal of Contemporary African Studies. 42 (1): 18, 23–24. doi:10.1080/02589001.2023.2287425. ISSN 0258-9001.

- ^ Matthews, Ron; Vivoda, Vlado (4 July 2023). "'Water Wars': strategic implications of the grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam". Conflict, Security & Development. 23 (4): 339. doi:10.1080/14678802.2023.2257137. ISSN 1467-8802.

- ^ Matthews, Ron; Vivoda, Vlado (4 July 2023). "'Water Wars': strategic implications of the grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam". Conflict, Security & Development. 23 (4): 349. doi:10.1080/14678802.2023.2257137. ISSN 1467-8802.

- ^ İlkbahar, Hasan; Mercan, Muhammed Hüseyin (2023). "Hydro-Hegemony, Counter-Hegemony and Neoclassical Realism on the Nile Basin: An Analysis of Egypt's Response to the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD)". Journal of Asian and African Studies. 60 (2): 7–8. doi:10.1177/00219096231188953. ISSN 0021-9096.

- ^ "The Nile Basin Initiative". Archived from the original on 27 June 2007.

- ^ Cambanis, Thanassis (25 September 2010). "Egypt and Thirsty Neighbors Are at Odds Over Nile". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ Elsanabary, Mohamed Helmy Mahmoud Moustafa (2012). Teleconnection, Modeling, Climate Anomalies Impact and Forecasting of Rainfall and Streamflow of the Upper Blue Nile River Basin (PhD thesis). Canada: University of Alberta. doi:10.7939/R3377641M. hdl:10402/era.28151.

- ^ a b Roussi, Antoaneta (23 July 2020). "Row over Africa's largest dam in danger of escalating, warn scientists". Nature. 583 (7817): 501–502. Bibcode:2020Natur.583..501R. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-02124-8. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 32669727.

- ^ Ranjan, Amit (2 January 2024). "Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam dispute: implications, negotiations, and mediations". Journal of Contemporary African Studies. 42 (1): 28–30. doi:10.1080/02589001.2023.2287425. ISSN 0258-9001.

- ^ Matthews, Ron; and Vivoda, Vlado (4 July 2023). "'Water Wars': strategic implications of the grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam". Conflict, Security & Development. 23 (4): 346. doi:10.1080/14678802.2023.2257137. ISSN 1467-8802.

- ^ İlkbahar, Hasan; Mercan, Muhammed Hüseyin (1 March 2025). "Hydro-Hegemony, Counter-Hegemony and Neoclassical Realism on the Nile Basin: An Analysis of Egypt's Response to the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD)". Journal of Asian and African Studies. 60 (2): 10. doi:10.1177/00219096231188953. ISSN 0021-9096.

- ^ Milas, Seifulaziz Leo (2013). Sharing the Nile: Egypt, Ethiopia and the geo-politics of water. London: Pluto Press. pp. 168–176. ISBN 978-1-84964-813-4.

- ^ Matthews, Ron; and Vivoda, Vlado (4 July 2023). "'Water Wars': strategic implications of the grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam". Conflict, Security & Development. 23 (4): 348–350. doi:10.1080/14678802.2023.2257137. ISSN 1467-8802.

- ^ Sutcliffe 2009, p. 350.

- ^ "Nile Basin National Water Quality". Nile Basin Initiative.

- ^ Hegab 2025.

- ^ Abotalib 2023.

- ^ Soliman 2006.

Sources

Books

- Dumont, Henri (2009). "A Description of the Nile Basin, and a Synopsis of Its History, Ecology, Biogeography, Hydrology, and Natural Resources". In Dumont, Henri (ed.). The Nile: Origin, Environments, Limnology and Human Use. Monographiae Biologicae. Springer Netherlands. pp. 1–22. ISBN 9781402097263. Retrieved 1 December 2025.

- Eggermont, Hilde; et al. (2009). "Rwenzori Mountains (Mountains of the Moon): Headwaters of the Nile". In Dumont, Henri (ed.). The Nile: Origin, Environments, Limnology and Human Use. Monographiae Biologicae. Springer Netherlands. pp. 243–262. ISBN 9781402097263. Retrieved 1 December 2025.

- El-Shabrawy, Gamal; Dumont, Henri (2009). "Lake Nasser-Nubia". In Dumont, Henri (ed.). The Nile: Origin, Environments, Limnology and Human Use. Monographiae Biologicae. Springer Netherlands. pp. 125–156. ISBN 9781402097263. Retrieved 1 December 2025.

- Garstin, William E.; Cana, Frank R. (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 692–699.

- Hamza, Waleed (2009). "The Nile Delta". In Dumont, Henri (ed.). The Nile: Origin, Environments, Limnology and Human Use. Monographiae Biologicae. Springer Netherlands. pp. 75–94. ISBN 9781402097263. Retrieved 1 December 2025.

- Okidi, C. O. (1994). "History of the Nile and Lake Victoria Basins through Treaties". In Howell, P.P.; Alan, J. J. (eds.). The Nile: Sharing a Scarce Resource. Cambridge University Press. pp. 321–350. ISBN 9780521450409. Retrieved 12 January 2026.

- Said, Rushdi (1981). The geological evolution of the River Nile. Springer Verlag. ISBN 3540904840. Retrieved 15 December 2025.

- Shahin, Mamdouh (2002). Hydrology and Water Resources of Africa. Springer Netherlands. ISBN 9781402008665. Retrieved 7 January 2026.

- Sutcliffe, John; et al. (2009). "The Hydrology of the Nile Basin". In Dumont, Henri (ed.). The Nile: Origin, Environments, Limnology and Human Use. Monographiae Biologicae. Springer Netherlands. pp. 334–364. ISBN 9781402097263. Retrieved 1 December 2025.

- Tvedt, Terje (2021). The Nile: History's Greatest River. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9780755616800. Retrieved 10 December 2025.

- Van Damme, Dirk; Bocxlaer, Bert (2009). "Freshwater Molluscs of the Nile Basin, Past and Present". In Dumont, Henri (ed.). The Nile: Origin, Environments, Limnology and Human Use. Monographiae Biologicae. Springer Netherlands. pp. 585–630. ISBN 9781402097263. Retrieved 1 December 2025.

- Williams, M.A.J. (1980). Evolution of Nile Basin. Balkema. ISBN 9061910129. Retrieved 15 December 2025.

- Williams, Martin; et al. (2009). "Late Quaternary Environments in Nile Basin". In Dumont, Henri (ed.). The Nile: Origin, Environments, Limnology and Human Use. Monographiae Biologicae. Springer Netherlands. pp. 61–72. ISBN 9781402097263. Retrieved 1 December 2025.

Journals and websites

- Abotalib, Abotalib; et al. (2023). "Irreversible and Large-Scale Heavy Metal Pollution Arising from Increased Damming and Untreated Water Reuse in the Nile Delta". Earth's Future. 11 (3) e2022EF002987. American Geophysical Union. doi:10.1029/2022EF002987. ISSN 2328-4277. Retrieved 31 December 2025.

- Hafez, Ahmed; et al. (2024). "Assessing the Influences of Future Water Development Projects in Tekeze-Atbara-Setit Basin on the Nile River Inflow at Aswan, Egypt". Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies. 56 102007. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/j.ejrh.2024.102007. ISSN 2214-5818. Retrieved 31 December 2025.

- Healy, R. W.; et al. (2007). "Water Budgets: Foundations for Effective Water-resources and Environmental Management}," (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 14 January 2026.

- Hegab, Mahmoud; et al. (March 2025). "Evaluating the Spatial Pattern of Water Quality of the Nile River". Scientific Reports. 15 7626. Nature Portfolio. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-89982-2. ISSN 2045-2322. Retrieved 31 December 2025.

- Hurst, Harold Edwin; et al. (2025). "Nile River". Britannica. Retrieved 11 December 2025.

- Khairy, A.; et al. (1998). "Water Contact Activities and Schistosomiasis Infection in menoufia, Nile Delta, Egypt". Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 4 (1). WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean: 100–106. ISSN 1687-1634. Retrieved 31 December 2025.

- Lemma, Hanibal; et al. (2019). "Bedload Transport Measurements in the Gilgel Abay River, Lake Tana Basin, Ethiopia". Journal of Hydrology. 577 123968. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2019.123968. ISSN 1879-2707. Retrieved 31 December 2025.

- Liu, Shaochuang; et al. (1 March 2009). "Pinpointing the sources and measuring the lengths of the principal rivers of the world". International Journal of Digital Earth . 2 (1): 80–87. doi:10.1080/17538940902746082. ISSN 1753-8955. S2CID 27548511. Archived from the original on 23 December 2018. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- McKenna, Amy; et al. (2025). "Blue Nile River". Britannica. Retrieved 31 December 2025.

- Senay, Gabriel; et al. (2014). "Understanding the Hydrologic Surces and Sinks in the Nile Basin Using Multisource Climate and Remote Sensing Data Sets". Water Resources Research. 50 (11). American Geophysical Union : 8625–8650. doi:10.1002/2013WR015231. ISSN 1944-7973. Retrieved 23 December 2025.

- Soliman, A.; et al. (2006). "Environmental Contamination and Toxicology: Geographical Clustering of Pancreatic Cancers in the Northeast Nile Delta Region of Egypt". Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 51 (1). Springer Science+Business Media: 142–148. doi:10.1007/s00244-005-0154-0. ISSN 1432-0703. Retrieved 31 December 2025.

Unknown author

- "Baḥr al-Ghazāl". Britannica. 2025. Retrieved 7 January 2026.

- "Nile Basin National Water Quality Monitoring Baseline Study Report for Egypt". Nile Basin Initiative. 2005. Retrieved 31 December 2025.

- Water Accounting in the Nile River Basin. Food and Agriculture Organization - United Nations. 2020. doi:10.4060/ca9895en. ISBN 9789251329825. Retrieved 11 December 2025.