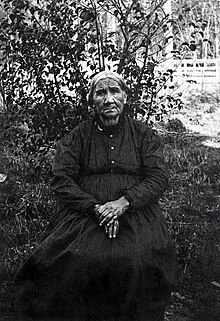

Margaret Grey Eyes Solomon (November 1816 – August 18, 1890), better known as Mother Solomon, was a Wyandot nanny.

Solomon was born along Owl Creek, Ohio, and her father took her to Indigenous sites as a child. After moving to the Big Spring Reservation in 1822, she learned housekeeping and English at a mission school and began attending the Wyandot Mission Church. Solomon married a Wyandot man in 1833. They had a few children, at least two of whom died. The Indian Removal Act forced Wyandots to move to Kansas in 1843, where many died of illness. Solomon recuperated with her family and had a few more children, though by 1860, her husband and remaining children had died. She sought to protect the Huron Indian Cemetery, their burial place. In Kansas, oxen, pigs, and horses were stolen from her.

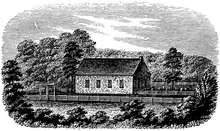

Solomon became homesick after marrying the sheriff John Solomon. Alongside her nephew, the Solomons relocated to Upper Sandusky, Ohio, in 1865. When John died in 1876, Margaret began babysitting children. Throughout the village, she garnered the nickname "Mother Solomon", promoted Wyandot culture, and advocated for the restoration of the run-down mission church. During its rededication in 1889, she sang a Wyandot translation of "Come Thou Fount of Every Blessing". Many attendees admired her stage presence. Solomon became weaker in her final years and died in 1890. She was a popular local figure, and the Wyandot County Museum has since displayed her belongings.

Early life and education

Margaret Grey Eyes Solomon was born in November 1816 along Owl Creek in Marion County, Ohio.[1][2][a] She was the eldest of four siblings and two half-siblings.[4][5] Her father was the Wyandot chief John "Squire" Grey Eyes,[b] and her mother was a Wyandot woman named Eliza.[2][3] Solomon's given name was of Christian origin.[6]

Squire encouraged family visits to Indigenous sites.[7] When Solomon was four, Squire brought her to the Olentangy Indian Caverns. She was too afraid to explore them, but understood the importance of the site and learned that generations of Wyandots held councils or hid from enemies in the caves.[8] Solomon and her family worked as hunters and traders along village footpaths. They moved into a small cabin on the Big Spring Reservation in 1822.[4][8] Solomon recited traditional Wyandot language teachings to her dolls at home, and Wyandots relayed oral tradition to her. Her uncle, chief Warpole, taught her the origin of their family name. Solomon once gathered with other children to hear him describe the origins of the Wyandots in Canada and their relocations to Michilimackinac, Detroit, and Upper Sandusky. He emphasized the importance of maintaining Wyandot culture to the children.[9]

Methodist missionaries were prominent in the reserve and converted many Wyandots; Squire was among a group of chiefs that requested the Methodist Episcopal Church to build a mission school in Upper Sandusky.[10] Upon its opening in 1821, Solomon was one of the first students to be enrolled.[11] She and the other schoolgirls were taught to weave, sew, knit, cook, and housekeep.[12] The missionary Harriet Stubbs taught Solomon hymns,[13] and at age 13, she was improving her English spelling and reading.[14] Solomon began attending the nearby Wyandot Mission Church as a child and eventually befriended each of its pastors.[15]

Two of Solomon's siblings married Wyandots from the Detroit River, and her family kept close relationships with the community there.[5] Solomon married David Young, a Wyandot man who had adopted a Christian name after becoming a Methodist preacher. They were married in the mission church on February 4, 1833, by the priest Thomas Simms.[16] Solomon and Young had at least three children in Ohio.[7][17]

Wyandot removal to Kansas

President Andrew Jackson's Indian Removal Act, calling for Indigenous communities to move west of the Mississippi River, passed in 1830.[18] Treaty commissioners in the region, spurred on by the federal government, began pressuring Wyandots to leave, and nearby Lenapes and Shawnees signed their own removal treaties. However, Wyandot scouting parties out west in 1831 and 1834 rejected their proposed land tracts. Tensions peaked in 1841 when white men murdered the head chief Summundewat.[19][20] Squire was against removing and only conceded when a Wyandot council voted two-thirds in favor. The Wyandots secured 25,000 acres within Kansas City, Kansas, then reluctantly signed a removal treaty in March 1842.[21]

On July 12, 1843, Solomon gathered alongside hundreds at the Wyandot Mission Church. They grieved, spread flowers across the adjacent cemetery, and heard Squire give a farewell speech in the Wyandot language.[6][22][23] Mrs. Parker, a white friend, cried and hugged Solomon before she left.[24] At least two of Solomon's children had died and were buried in the mission church cemetery,[17] and she reportedly felt distraught leaving them behind.[25] Around 664 Wyandots arrived in Cincinnati, Ohio, after a week of travel by wagon, horse, and foot. They were harassed by whiskey traders before boarding two steamships, and in Kansas, a territorial dispute forced many to camp in flooded lowlands. Eye inflammation, measles, and severe diarrhea were widespread, and 18% of the removed Wyandots had died by 1844.[26]

In Kansas, Young began work as a ferryman while Solomon recuperated with her family.[27] The two settled in a small house built around December 1843 then ordered saplings and seeds from a nursery in Ohio. They began an apple tree orchard and a garden of corn, beans, and potatoes. Although the soil had not been plowed and the first summer was extremely hot, they continued to cultivate the garden.[28] Solomon had a few more children,[27] totaling three boys and five girls. However, none of her children born in Ohio or Kansas lived past adolescence.[4] Her two-year-old son died in 1848, and another son died of remittent fever a year later. She had only three living daughters by 1851. That year, Young died of tuberculosis, and in 1852, a daughter died of cholera. By the end of the decade, Solomon had buried her entire family in the Huron Indian Cemetery, which had replaced the mission school and church as a Wyandot fixture.[27][29] Forced enfranchisement threatened her community's legal status, so she continuously tried to prove the cemetery's importance.[30]

A gray horse, bay horse, and brown mare, worth $195 combined,[c] were stolen from Solomon in September 1848, which she attributed to emigrants traveling the Oregon Trail. Further thefts occurred that fall to 30 of her pigs, worth $90 in total.[d] Possessions totaling $580,[e] including oxen and horses, were stolen from her between 1855 and 1859. In one case, a housekeeper named James Cook reportedly fled after stealing $225 worth of gold coins from a trunk owned by her brother.[f] Solomon's friend Catherine Johnson corroborated each theft committed against her in Kansas.[32]

Return to Ohio

Margaret married the Wyandot sheriff John Solomon in 1860,[33][g] and afterwards, was struck by homesickness.[15][34] She convinced John and her nephew, Jimmy Guyami, to return to Ohio with her.[15] Her and John's two-acre land tract on the south end of Tauromee Street was to be put up for auction in October 1862.[35] The three returned to Upper Sandusky in 1865 and settled in a small cabin she previously lived in.[15] The cabin had rafters which Solomon hung corn from to dry, as well as a porch.[36] According to Labelle, "there was little left of the old reservation." The community council house burned down in 1851, and the roof and walls of the mission church had begun to collapse, although a few grave sites and houses remained.[37]

John worked as a tailor until his death on December 14, 1876.[4][15] Now 60 and widowed a second time, Margaret began babysitting the neighborhood children, and she often sought to help struggling families.[15][38] She also became a surrogate mother.[15] The historian Kathryn Magee Labelle described her childcare as tireless and daily, and the village nicknamed her "Mother Solomon" out of respect.[39] Solomon promoted Wyandot culture throughout the village and demonstrated the Wyandot language in community gatherings and public presentations. She taught children about the connections between their ancestors and Wyandots by repeating stories her elders had told.[37] The Hocking Sentinel described her storytelling as "full of interest and romance". A writer for the newspaper claimed to have visited Solomon often and stated that she spoke for hours about early Wyandot history and her childhood.[40] In 1881, Solomon briefly visited her relatives in Kansas, who had sent many invitations.[4] She gave away paintings of the chiefs Mononcue and Between-the-Logs in 1883, and allowed them to be reproduced.[41]

Solomon advocated for the village to restore and continue operating the run-down mission church as a means to preserve part of the historical record of Wyandots in Ohio. In 1888, under a $2,000 budget,[h] the General Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church began repairs.[42] On September 21, 1889, the Central Ohio Conference held a rededication ceremony.[42][43] Guyami was among the estimated 3,000 attendees that afternoon.[43][44] General William H. Gibson was among the ministers who gave speeches,[45] and Elnathan C. Gavitt, the only former missionary in attendance, spoke fondly about his time there.[46] Solomon was the only Wyandot removed in 1843 to attend.[42][45] At the age of 72, she sang a Wyandot translation of "Come Thou Fount of Every Blessing", a hymn she had learned at the church.[17] The Urbana Daily Citizen's J. W. Henley called her an "object of great interest".[43] The Western Christian Advocate agreed and described her as "strong and well preserved".[46] Many attendees found beauty in her native language,[17] and The Bryan-College Station Eagle thought she sang in a "sweet, clear voice".[44] As the participants of the service circulated and shook hands, the Western Christian Advocate concluded: "Mother Solomon, and many others, became very happy, and rejoiced, and shouted the praises of God."[46]

In her final years, Solomon sensed she was weakening.[15] N. B. C. Love, an organizer of the mission church's rededication,[45] reported in 1889: "Native to this soil, she expects before many years to lie down in it, as in the arms of a loving mother, while with the Christian's hope she sings of 'The Land That Is Fairer than Day,' where she expects to meet the loved ones of her people."[47] By July 1890, Solomon agreed to move into the home of Mr. and Mrs. Jacob Hayman.[15] There, she signed a document objecting to the removal of remains in the Huron Indian Cemetery.[30]

Death and legacy

Solomon died on August 18, 1890. Her funeral was held at the Wyandot Mission Church two days later.[15][48] Despite a downpour that morning, a large crowd gathered with people from across Wyandot County. The pastor G. Lease led the service and called her a noble woman.[48][49] Solomon's death was widely reported in local newspapers, and these stories emphasized her father's role as chief, her removal to Kansas and return to Ohio, and her work as a nanny. The historian Kathryn Magee Labelle referred to the coverage as a "momentary acknowledgement of [Wyandot] resilience in Ohio". Though, many stories falsely called Solomon "the last of the Wyandots", which she attributed to the prominent Vanishing Indian stereotype and an attempt at erasing Wyandots from Ohio.[48]

Solomon was a popular local figure. According to the archivist Thelma R. Marsh, she was "almost a legend" when she died.[3][50] Many adults attested to being raised by Solomon, and some deemed it an honor. Labelle thought that her attainment of the honorific "Mother", rather than the lesser "Sister" or "Auntie", indicated success in her work. She ascribed Solomon to a Midwestern, 19th-century wave of mothers who sought to mediate between settler and Indigenous groups.[51]

In February 1931, the Wyandot County Museum displayed a century-old chair built by Solomon that featured a woven shagbark hickory seat and no nails.[52] They dedicated a glass case to her in May 1971 with her glasses, smoking pipe, beaded purse, candle molds, woven basket, and portrait.[53] An exception to the limited studies on Solomon is Marsh's 1984 children's book Daughter of Grey Eyes: The Story of Mother Solomon. It spans 60 pages and draws from archival material, journal articles, and family interviews.[3] On the morning of August 12, 1990, Marsh led a service at the mission church commemorating the centennial of Solomon's funeral.[54] She died and was buried there two years later. In October 2016, the church held an event celebrating the bicentennial of missionaries in Ohio, and Solomon's life was recounted during a tour of the cemetery attended by 192.[55] The McCutchen Overland Inn Museum displayed her saddle in the Anderson General Store in May 2021.[56]

Notes

- ^ Variations on her surname include "Greyeyes" and "Grey-Eyes",[3] sometimes with the spelling "Gray".[4] The Marion Star, The Cincinnati Enquirer, and Ronald I. Marvin Jr. cite November 26, 27 and 29, respectively, as her birthdate.[1][2][4] The Cincinnati Enquirer cites Wayne County as her birthplace.[4]

- ^ Kathryn Magee Labelle cites "Lewis" as his given name.[3]

- ^ Equivalent to $4,800 in 2024.[31]

- ^ Equivalent to $2,200 in 2024.[31]

- ^ Equivalent to $14,000 in 2024.[31]

- ^ Equivalent to $5,600 in 2024.[31]

- ^ The Cincinnati Enquirer and Ronald I. Marvin Jr. cite 1858 as the year of marriage.[4][15]

- ^ Equivalent to $70,000 in 2024.[31]

References

- ^ a b Moran, Joyce (June 14, 1987). "Indian Chief Visits Home of Forebears". The Marion Star. p. 22 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Marvin Jr. 2015, p. 38.

- ^ a b c d e Labelle 2021, p. 53.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Mother Solomon. Last of the Wyandot Indian Tribe in This State". The Cincinnati Enquirer. September 29, 1889. p. 19 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Labelle 2021, pp. 53–54.

- ^ a b Wood, Lucy (June 14, 1987). "Wyandott Mission Retains Sacred Air". The Marion Star. p. 22 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Little 2023, p. 118.

- ^ a b Labelle 2021, p. 55.

- ^ Labelle 2021, pp. 53, 62–63.

- ^ Labelle 2021, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Marvin Jr. 2015, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Labelle 2021, p. 57.

- ^ Stevenson, R. T. (January 12, 1916). "Centennial of the Wyandot Mission: 1816-1916". Western Christian Advocate. p. 6 – via NewspaperArchive.

- ^ Little 2023, pp. 119–120.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Marvin Jr. 2015, p. 39.

- ^ Labelle 2021, p. 54.

- ^ a b c d Labelle 2021, p. 64.

- ^ Labelle 2021, p. 51.

- ^ Littlefield Jr. & Parins 2011, pp. 273–274.

- ^ Labelle 2021, p. 59.

- ^ Labelle 2021, p. 58.

- ^ Labelle 2021, pp. 52, 59.

- ^ Wolf, Jeannie Wiley (May 14, 2023). "Old Mission Church Still Holding Services After 199 Years". The Courier. Archived from the original on April 27, 2024. Retrieved February 22, 2025.

- ^ Kelly 2024, p. 113.

- ^ Little 2023, p. 87.

- ^ Labelle 2021, pp. 59–61.

- ^ a b c Labelle 2021, p. 61.

- ^ Kelly 2024, pp. 130, 284.

- ^ Kelly 2024, p. 111.

- ^ a b Labelle 2021, pp. 90–91.

- ^ a b c d e 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Report of the Commissioners Appointed in Accordance with the Senate Amendment of the 13th Article of the Treaty of 23d of February, 1867, Embracing the Claims of the Wyandott Indians. Index to the Senate Executive Documents for the Second Session of the Forty-First Congress of the United States of America. 1869–'70. (Report). Vol. 2. United States Government Printing Office. 1870. p. 12–13.

- ^ Labelle 2021, pp. 54, 64.

- ^ Labelle 2021, p. 62.

- ^ Wood, Luther H. (May 25, 1862). "Sheriff's Sale". The Olathe News. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Beaded Cap Made by Last Wyandotte Indian in Ohio Prized by Local Woman". The Bluffton News. June 9, 1949. p. 1 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ a b Labelle 2021, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Labelle 2021, pp. 54, 62.

- ^ Labelle 2021, p. 52.

- ^ "The Last of the Wyandottes". The Hocking Sentinel. September 4, 1890. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Schlup, Emil (April 1906). "The Wyandot Mission". Ohio Archaeological and Historical Publications. 15: 169, 177. Archived from the original on May 4, 2024. Retrieved May 4, 2024.

- ^ a b c Labelle 2021, p. 63.

- ^ a b c Henley, J. W. (September 25, 1889). "Rev. J. W. Henley Describes the City and the M. E. Conference Recently Held There". Urbana Daily Citizen. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Famous Old Church". Bryan-College Station Eagle. June 11, 1897. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c King, I. F. (October 1901). "Introduction of Methodism in Ohio". Ohio Archaeological and Historical Publications. 10: 203. Archived from the original on May 5, 2024. Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ^ a b c B., T. N. (October 2, 1889). "Re-dedication of the Wyandot Mission Church". Western Christian Advocate. p. 4 – via NewspaperArchive.

- ^ Love, N. B. C. (March 5, 1889). "The Exodus of the Wyandots". Telegraph-Forum. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Labelle 2021, p. 65.

- ^ "Last of the Wyandots". Cincinnati Commercial Gazette. August 20, 1890. p. 2 – via NewspaperArchive.

- ^ "Wyandotte Indian Tribe Gets Paid for ¼ of Ohio". Dayton Daily News. February 17, 1985. p. 13 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Labelle 2021, pp. 52, 62.

- ^ "Indian Chair 100-Years Old". East Liverpool Review. February 12, 1931. p. 8 – via NewspaperArchive.

- ^ Mathern, Jeanette (May 19, 1971). "Museum Inspires Recollections of Yesterday". Carey Progressor. p. 1 – via NewspaperArchive.

- ^ "Mother Solomon Funeral to Be Remembered Sunday". Telegraph-Forum. August 11, 1990. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Labelle 2021, pp. 53, 66–67.

- ^ Wolf, Jeannie Wiley (July 13, 2021). "Overland Inn Museum Reopens Century-Old General Store". The Courier. Archived from the original on May 8, 2024. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

Bibliography

- Kelly, Mckelvey (2024). Landscapes of Love: Waⁿdat Women and the Politics of Removal, 1795–1910 (PhD thesis). University of Saskatchewan.

- Labelle, Kathryn Magee (2021). Daughters of Aataentsic: Life Stories from Seven Generations. McGill–Queen's University Press. doi:10.1515/9780228006886-007. ISBN 978-0-228-00688-6.

- Little, Tarisa Dawn (2023). 'To Those Who Say We Are Assimilated, I Say Hogwash!': A History of the Wyandot of Anderdon Day School Experience, 1790 to 1915 (PhD thesis). University of Saskatchewan.

- Littlefield Jr., Daniel F.; Parins, James W., eds. (2011). Encyclopedia of American Indian Removal. Vol. 1. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-36042-8.

- Marvin Jr., Ronald I. (2015). A Brief History of Wyandot County, Ohio. The History Press. ISBN 978-1-62585-535-0.