Hongwu Emperor

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Rise to power |

||

The Hongwu Emperor (21 October 1328[iii] – 24 June 1398), personal name Zhu Yuanzhang,[xii] was the founding emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1368 to 1398.

In the mid-14th century, China suffered from epidemics, famines, and widespread uprisings under the Mongol Yuan dynasty. During this turmoil, the orphaned Zhu Yuanzhang briefly lived as a novice monk, begging for alms and gaining insight into common people's hardships, while developing a dislike for book-dependent scholars.[10] In 1352, he joined a rebel force, soon proving his ability and rising to command his own army. He captured Nanjing in 1356 and made it his capital, creating a government of generals and Confucian scholars and rejecting Mongol rule. He adopted Yuan administrative practices and applied them to his territory as it expanded. After defeating rival rebels, most notably in his decisive victory over Chen Youliang at Lake Poyang in 1363, he declared himself King of Wu[xiii] in 1364. Nevertheless, in 1367 he formally recognized Han Lin'er, the Red Turban leader who claimed Song legitimacy.

In early 1368, after successfully dominating southern and central China, Zhu chose to rename his state. He decided on the name Da Ming, which translates to "Great Radiance", for his empire, and designated Hongwu, meaning "Vastly Martial", as the name of the era and the motto of his reign. In the following four-year war, he drove out the Mongol armies loyal to the Yuan dynasty and unified the country, but his attempt to conquer Mongolia ended in failure. During the Hongwu Emperor's thirty-year reign, Ming China experienced significant growth and recovered from the effects of prolonged wars. The Emperor had a strong understanding of the structure of society and believed in implementing reforms to improve institutions. This approach differed from the Confucian belief that the ruler's moral example was the most important factor.[11] The Hongwu Emperor also prioritized the safety of his people and the loyalty of his subordinates, demonstrating pragmatism and caution in military affairs. He maintained a disciplined army and made efforts to minimize the impact of war on civilians.[12]

Although the peak of his political system crumbled in a civil war shortly after his death, other results of the Hongwu Emperor's reforms, such as local and regional institutions for Ming state administration and self-government, as well as the financial and examination systems, proved to be resilient.[11] The census, land registration and tax system, and the Weisuo military system all endured until the end of the dynasty.[11] His descendants continued to rule over all of China until 1644, and the southern region for an additional seventeen years.[13][14]

Youth

Zhu Yuanzhang, the future Hongwu Emperor, was born in 1328 in Zhongli (鍾離) village, in Haozhou (present-day Fengyang, Anhui), then under the rule of the Mongol Yuan dynasty. He was the youngest of four sons in a poor peasant family.[15][16] He was given the name Zhu Chongba (朱重八) at birth,[17] but used the name Zhu Xingzong (朱興宗) in adulthood.[2] Later, as a rebel fighter against the Yuan dynasty, he used the name Zhu Yuanzhang, with the courtesy name Guorui.[18] Zhu's father, Zhu Wusi, lived in Nanjing but fled to the countryside to avoid tax collectors. His paternal grandfather was a gold miner, and his maternal grandfather was a fortune-teller and seer. In 1344, during a plague epidemic, Zhu Xingzong's parents and two of his brothers died.[19]

Zhu then entered a local Buddhist monastery.[19] For the next three years, he wandered as a mendicant monk, becoming familiar with the landscape and people of eastern Henan and northern Anhui.[20] He returned to the monastery in 1348 and stayed for four years, during which he learned to read, write, and study the basics of Buddhism.[21]

As rebel

The harsh taxation policies, famine, and catastrophic flooding in the Yellow River basin, caused by inadequate flood control measures, led to widespread opposition to the rule of the Yuan dynasty.[22] This discontent was further fueled by the presence of Taoist and Buddhist secret societies and sects, with the most prominent being the White Lotus society.[23] In 1351, the Red Turban Rebellion erupted and quickly spread throughout northern China.[22]

The initially disorganized Mongol troops were able to launch a counteroffensive and advance along the Grand Canal.[24] In October 1352, the Mongols captured Xuzhou, causing the rebel commanders Peng Da and Zhao Yunyong to flee south to Haozhou,[24] where the Yuan dynasty's power was declining. In Haozhou, Guo Zixing, Sun Deya (孫德崖), and three other leaders, with the support of the local elite, organized the army and took control in order to establish order in the surrounding area.[24] Guo submitted to Peng, while his four colleagues submitted to Zhao.[24]

In 1352, when the Yuan army burned down the monastery after suspecting the monks of links to the White Lotus society, Zhu joined the rebels.[25] On 15 April of the same year, he arrived in Haozhou.[24] While Zhu was considered physically unattractive[10] and he began as a rank-and-file fighter, his exceptional leadership, decisiveness, martial skill, and intelligence quickly earned him significant authority.[26] He became the leader among 24 of his acquaintances who had already joined the rebels. These acquaintances would eventually become generals in the Ming army.[27] By the spring of 1353, Zhu was leading a 700-man squad, and he became Guo's most trusted subordinate.[24] Skilled in both military tactics and political maneuvering, he even married Guo's adopted daughter, surnamed Ma.[28] Unlike other leaders of his time, Zhu had a small number of relatives who were appointed to important positions, at a time when family ties were crucial for ensuring loyalty and reliability.[24]

The rivalry between Peng and Zhao escalated into a full-blown conflict. Guo was initially captured, but his sons and Zhu freed him. This increased Guo's reliance on Zhu.[29] After Peng's death in 1353, Zhao emerged as the dominant leader in the region.[30] He sent Guo to the east and Zhu with a small detachment to the south, hoping to divide them and destroy them. However, Zhu successfully occupied several counties and bolstered his army to 20,000 soldiers, and Guo moved with Zhao's ten thousand men to join him.[30]

Regional ruler

Establishment in Nanjing (1355–1360)

In the beginning of 1355, Zhu, Guo, and the eastern rebel Zhang Shicheng decided to leave the devastated northern territories and cross the Yangtze River into the still-prosperous south.[31] Guo and Zhu entered into a dispute over Hezhou, a city situated on the banks of the Yangtze, leading Zhu to ally with Guo's old enemy Sun Deya, but Guo died before the conflict escalated.[32] Han Lin'er, the Red Turban leader who claimed the title of Song emperor, then appointed Guo's eldest son, Guo Tianxu (郭天敍),[33] as his successor, with Zhang Tianyu (張天祐), Guo's brother-in-law, as first deputy and Zhu as second deputy.[16] In July 1355, the Hezhou rebels obtained a fleet from rebels arriving from Chao Lake, allowing them to cross the Yangtze that same month.[32] Zhu defeated the local Yuan commander Chen Yexian (陳野先), who surrendered to him, but Chen betrayed Guo Tianxu during an attack on Jiqing (present-day Nanjing) in September 1355. Chen, Guo Tianxu, and Zhang Tianyu all died in the subsequent fighting.[34]

In March 1356, Zhu once again marched on Jiqing. Chen Yexian's nephew Chen Zhaoxian (陳兆先) had succeeded his uncle as the Mongol commander. He and 36,000 men surrendered to Zhu. In April 1356, Zhu successfully entered Jiqing,[34] which he renamed Yingtian ("In response to Heaven").[35] In May 1356, Han appointed Zhu as the head of Jiangnan Province, one of the five provinces of the Song state.[36] Zhu soon had Guo's younger son executed, citing a breach of military discipline. This allowed Zhu to establish clear leadership and he immediately began to build his administration, but he faced instances of betrayal and defection to the enemy until the victory at Lake Poyang in 1363.[34][37]

Zhu was now in command of an army of 100,000 soldiers, which was divided into divisions or wings (翼; yi). In Nanjing itself, there were eight divisions and one per prefecture.[38] From 1355 to 1357, he launched attacks against Zhang Shicheng in the direction of Suzhou and successfully occupied southern Jiangxi;[xiv] after this, the border with Zhang's state was fortified on both sides and remained stable until 1366.[38] In Zhejiang, from 1358 to 1359, Zhu controlled four impoverished inland prefectures,[38] while Zhang held control over four prosperous northern coastal prefectures, and Fang Guozhen occupied the eastern coast of the province.[39]

In the summer of 1359, the Mongol warlord Chaghan Temur drove Han Lin'er from Kaifeng. With only a few hundred soldiers left, Han survived in Anfeng, a prefectural city in the west of Anhui, while Chaghan Temur turned to Shandong.[30] After this retreat, Song authority collapsed rapidly; aside from Zhu's effectively autonomous Jiangnan, no Song province remained after 1362.[40] In 1361, Han appointed Zhu as Duke of Wu (Wu Guogong)[36][xiii] and acknowledged his control over conquered territories.[41] Fearing a Yuan advance toward Nanjing, Zhu initially sought cooperation with Chaghan Temur, but after the latter was assassinated in 1362, the Yuan ceased to be a threat and Zhu rejected their offer to make him governor of Jiangxi.[42]

Zhu did not embrace Red Turban ideology; instead of building a new elite based on White Lotus Manichean-Buddhist beliefs, he aligned himself with Confucian scholars.[43] This shift transformed him from a sectarian rebel into a political leader seeking traditional legitimacy, though he still relied on officers devoted to White Lotus teachings.[44]

Zhu's political base strengthened through his collaboration with Li Shanchang, a landowner from Dingyuan who managed civil administration as Zhu expanded.[45] In 1360, after repeated requests, leading scholars such as Song Lian and Liu Ji joined him.[46] Known as the Jinhua school,[xv] they envisioned a unified state with a small but efficient bureaucracy, opposed the corruption of late Yuan rule,[47][48] and believed that state institutions could improve public morals. Though their motives differed from Zhu's, they shared his commitment to reform through a strong state and active monarchy.[49]

As an independent ruler, Zhu promoted moderate taxation, unlike other rebel leaders and generals who frequently seized peasants' grain for military needs.[50] He emphasized orderly governance and peaceful life for the population, working with local elites and understanding villagers' needs due to his own peasant background.[51] Zhu's principles strengthened the economy of his territories: he began minting coins in 1361, created monopolies on salt and tea, and resumed collecting customs duties in 1362. These policies increased tax revenues and helped finance his military campaigns.[46]

Conquest of Han (1360–1365)

In the beginning of 1360, Zhu controlled the southwestern part of Jiangsu, all of Anhui south of the Yangtze River, and the inland of Zhejiang. By 1393, these territories had a population of 7.8 million.[39] Zhang Shicheng's Kingdom of Wu[xiii] had comparable power with a larger population but worse organization. Chen Youlang's state of Han had a similar situation.[39] The state of Han, located west of Zhu's territory, included the provinces of Jiangxi and Hubei. Zhang, based in Suzhou, controlled the lower reaches of the Yangtze, from the eastern borders of Zhu's dominions to the sea. While Zhu, Zhang, and Chen divided up the Yangtze River Basin, the rest of southern and central China was largely under the control of "one-province" regimes. Fang Guozhen controlled the eastern Chinese coast, Ming Yuzhen ruled in Sichuan, and a trio of Yuan loyalists (Chen Youding, He Zhen, and Basalawarmi) controlled Fujian, Guangdong, and Yunnan. These provincial regimes were unable to threaten the states of Song, Wu, and Han, but they were strong in defense.[39]

The war between Song and Han from 1360 to 1363 had a devastating impact on the balance of power in the Yangtze River Basin. This conflict increased Zhu's prestige and gave him a significant advantage over his rivals.[39] The fighting began when the Han army attacked Nanjing in 1360, but Zhu quickly defeated them.[52] In 1361, the war spread to the Han province of Jiangxi, which changed hands multiple times.[53] By 1362, Zhu had gained control of Jiangxi.[54]

In January 1363, Zhang Shicheng's army launched a surprise attack on Anfeng, the residence of Song emperor Han Lin'er, resulting in the death of Han Lin'er's minister Liu Futong. Zhu offered his army to assist Han, who was still highly respected among the troops.[55] As a result, the powerless Han was relocated to Chuzhou, west of Nanjing on the opposite side of the Yangtze River.[56] However, the army remained stationed in the north until August 1363.[57]

The departure of Zhu's main forces to the north presented Chen Youliang with an opportunity to turn the tide of the war. He quickly raised an army of 300,000, outnumbering Zhu's remaining forces.[57] Chen planned to capture Nanchang and rally the local leaders in Jiangxi to join his cause and attack Nanjing,[57] but the Nanchang garrison, led by Deng Yu, held out until early June 1363. In mid-August, Zhu's army and fleet finally set out from Nanjing with approximately 100,000 soldiers.[58] Zhu's fleet defeated Chen's fleet in the battle of Lake Poyang in September 1363, and Chen was killed during the fighting.[59]

In 1364–1365, Zhu focused on conquering and absorbing the Han's territories. Numerous Han prefectural and county commanders surrendered without resistance. By early 1365, Generals Chang Yuchun and Deng Yu had gained control over central and southern Jiangxi, and General Xu Da had pacified Huguang.[60] This annexation of territories provided Zhu with a significant population advantage over his adversaries. The main threats to Zhu at this time were the Mongol warlord Köke Temür in northern China and Zhang Shicheng, who was based in Suzhou.[61]

Expansion of the army with former Han troops required a reorganization of the military.[62] Therefore, in 1364, Zhu implemented the Weisuo system, which involved the formation of guards (wei) comprising 5,600 soldiers. These guards were further divided into 5 battalions (qianhusuo) of 1,120 soldiers each, with 10 companies (baihusuo) in each battalion.[63] After 1364, the army was made up of 17 guards consisting of veterans who had previously served before 1363. The older veterans were demobilized, while the others were assigned to the garrison in Nanjing where they worked as peasants, using their production to provide food for the army.[64] Additional soldiers with shorter periods of service were acquired during the conquest of southern Anhui and central Zhejiang. They were stationed in the former Han territory, with field armies concentrated in Nanchang and Wuchang and garrisons scattered across Jiangxi and Huguang.[65] The remaining soldiers, mostly former Han soldiers, were joined by some veterans in the field armies sent to fight against Zhang's state of Wu under the leadership of Generals Xu and Chang.[65]

Conquest of Zhang's Wu and proclamation of the Ming (1364–1368)

After Chen Youliang's defeat, Zhu used the title of King of Wu (Wu wang) starting from the new year (4 February) of 1364. Zhang Shicheng had used the same title since October 1363.[66][xiii] Zhu still acknowledged his subordinate status to Han Lin'er and used the Song era of Longfeng as long as Han was alive, but he ran his own administration, following the model of the Yuan dynasty.[66]

In 1365–67, Zhu conquered Zhang's state of Wu. Zhang attempted to attack in late 1364, before Zhu could exploit the potential of the newly conquered territories, but Zhu repulsed Zhang's offensive in the spring of 1365.[67] Before launching a final attack on Zhang's heartland, the Suzhou region, Zhu and his generals decided to first "cut off the wings" of Zhang's state by occupying the territory north of the Yangtze and the Zhang-controlled part of Zhejiang. Zhu appointed Xu Da as the supreme commander of the attacking troops, and the attacking army easily captured the area due to its superiority. The ten-month siege of Suzhou began in December 1366.[68]

In January 1367, Han Lin'er drowned in the Yangtze River.[56] Zhu's state of Wu declared its official independence and proclaimed the year 1367 as the "first year of the Wu era". A year later, in 1368, Zhu proclaimed himself emperor and changed the name of the state. He followed the Mongol tradition of elevating titles[69] and named the empire "Great Ming" (Da Ming; 大明). He also designated 1368 as the "first year of the Hongwu era" (洪武).[70]

Unification of China

In the autumn of 1367, Zhu's troops launched an attack against Fang Guozhen. By December of that year, they had successfully taken control of the entire coast.[71] In November 1367, Hu Mei's army, along with the fleets of Tang He and Liao Yongzhong, began their journey south. By February 1368, they had easily conquered Fujian, and by April 1368, they had taken control of Guangdong. In July 1368, with the reinforcement of Yang Jing's army from Huguang, Guangxi province was also occupied.[72]

At the same time as the southern campaign, Zhu sent a 250,000-strong army, led by Xu Da and Chang Yuchun, to conquer the North China Plain.[73] By March 1368, both land and naval forces had successfully captured Shandong.[72] In May, Henan was also occupied.[74] A pause was taken for agricultural work, during which the Hongwu Emperor met with his generals in the captured city of Kaifeng to confirm plans for the campaign.[75] The Ming army resumed its march in mid-August and reached Dadu (present-day Beijing) in early September. They defeated the Mongol army outside Dadu and then occupied the city, while the Yuan emperor Toghon Temür fled north to Shangdu. The Chinese renamed Dadu to Beiping (Pacified North).[76] The campaign then continued with an attack on Shanxi.[77]

In January 1369, the main army, led by Xu Da, captured Taiyuan, while Köke Temür retreated to Gansu. In the spring of 1369, Ming troops also began to occupy Shaanxi.[78] They had fully captured the province by September 1369, but border skirmishes with Köke Temür's troops persisted until 1370.[79]

In 1370, the Ming government launched a two-pronged attack on Mongolia. Generals Li Wenzhong and Feng Sheng led an attack from Beijing to the north, while Xu Da attacked from Xi'an against Köke Temür.[80][81] In early May 1370, Köke Temür was defeated and fled to Karakorum. The Ming forces captured over 84,000 of his troops and continued to advance westward along the Yellow River.[82] At the same time, Li's forces advanced to Shangdu, while the Yuan emperor Toghon Temür retreated further north to Yingchang and died in May 1370. His son Ayushiridara then assumed the imperial title. In June, Li conquered Yingchang. Ayushiridara escaped, but the Ming army captured his wife and son, Maidilibala, along with more than 50,000 soldiers.[83] Ayushiridara continued to flee until reaching Karakorum, where the remnants of Köke Temür's army joined him.[83]

After successfully defeating the Mongols, the Ming government shifted its focus to the Xia state in Sichuan,[84] which maintained positive relations with the Ming but refused to submit. The Emperor ordered General Fu Youde to lead an attack from the north in 1371. Simultaneously, Tang He and Liao Yongzhong advanced with a fleet up the Yangtze River.[84] Although they initially faced resistance, they were able to push forward with the help of artillery and the enemy's decision to send part of their defenders north against the Ming army's successful advance. By September 1371, Sichuan had been conquered.[85] This victory ensured stability in the southwestern border for the next ten years, until the Ming conquered the pro-Mongol Yunnan in 1381–1382.[86]

In 1372, the Emperor launched a massive attack on Mongolia, with Xu Da leading a 150,000-strong army from Shanxi through the Gobi to Karakorum. In the west, Feng Sheng was assigned to conquer the western part of the Gansu Corridor with 50,000 cavalrymen, while Li Wenzhong was tasked with attacking eastern Mongolia and Manchuria with another 50,000 soldiers.[85] Although Feng's forces were able to successfully complete their mission, the Mongols defeated Xu and Li's armies.[87]

These failures in 1372 shattered the Hongwu Emperor's dream of becoming the heir to the entire Yuan Empire, both in China and on the steppe.[88] Furthermore, Japanese piracy increased and rebellions broke out in the provinces of Guangxi, Huguang, Sichuan, and Shaanxi.[87] As a result, the Chinese forces in the north shifted their focus to defense, and two years later returned the captured prince Maidilibala to Mongolia.[89]

1370s: State-building

Goals and law

A favorite passage of the Hongwu Emperor

from Daode jing (The Way and Its Power):[90] Let the state be small and the people few:

So that the people...

- fearing death, will be reluctant to move great distances

- and, even if they have boats and carts, will not use them.

So that the people...

- will find their food sweet and their clothes beautiful,

- will be content with where they live and happy in their customs.

Though adjoining states be within sight of one another

- and cocks crowing and dogs barking in one be heard in the next,

- yet the people of one state will grow old and die

- without having had any dealings with those of another.

The Hongwu Emperor demonstrated sympathy for the peasants in his public statements, and held a deep distrust of the wealthy landowners and scholars.[21] He often referred to himself as a villager from the right bank of the Huai River.[91] His difficult upbringing never left his mind, and even as emperor, he held onto the ideal of a self-sufficient village life in peace. He made every effort to make this dream a reality for his subjects.[92] The ultimate goal of the Emperor's reforms was to achieve political stability for the state. All policies, institutions, and the social and economic structure of society were designed to serve this purpose. The chaos and foreign rule that led to the establishment of a new dynasty only reinforced his determination to maintain order.[93]

The Emperor was meticulous in his efforts to establish a new society after the fall of the Yuan dynasty. He was a dynamic and innovative legislator, constantly issuing, revising, and modifying laws throughout his reign,[94] but these frequent changes sometimes sparked protests from officials.[95] The Emperor's legislation focused on four main themes: the restoration of order and morality in society, the regulation of the bureaucracy, the removal of corrupt and unreliable officials, and the prevention of the natural decline that comes with time. As the patriarch of the family, he aimed to prevent the decay of society and the dynasty in the future, as well as any changes to his laws.[96]

The compilation of the new code, known as the Great Ming Code, began in 1364. This code, which was heavily influenced by Confucian principles, was largely based on the old Tang Code of 653. The initial wording was agreed upon in 1367, and the final version was adopted in 1397. It remained unchanged until the fall of the empire, although additional provisions were later added.[97]

Capital city

The capital of the empire was Nanjing (Southern Capital), which was known as Yingtian until 1368. In the 1360s and 1370s, Nanjing underwent extensive construction. A workforce of 200,000 individuals surrounded the city with walls that were almost 26 km long, making them the longest in the world at the time. Additionally, an imperial palace and government quarter were built.[98] In 1368, the Emperor resided in Kaifeng during the months of June–August and October–November, leading to the city being known as Beijing (Northern Capital).[99]

In 1369, the Hongwu Emperor proposed a debate on the relocation of the capital. In August of that year, it was decided that the capital would be moved to Fengyang (then known as Linhuai), his hometown in northern Anhui.[100] Construction of the future capital, named Zhongdu (中都; 'Central Capital'), began with grand plans. The area had been largely abandoned since the famine of the 1340s, so landless families from the south were resettled in Fengyang.[101] In 1375, the Emperor ultimately abandoned the idea of relocating the capital and the construction was halted.[100]

Central government

Upon ascending to the throne, the Hongwu Emperor appointed his wife, Lady Ma, as empress and his eldest son, Zhu Biao, as his heir.[70] He surrounded himself with a group of military and civilian figures, but the civil officials never attained the same level of prestige and influence as the military.[103] In 1367, he granted the title of duke (gong) to three of his closest collaborators—the generals Xu Da and Chang Yuchun and the official Li Shanchang.[103] After establishing the Ming dynasty, he also bestowed ranks and titles upon a wider circle of loyal generals.[xvi] These military leaders were chosen based on their abilities, but their positions were often inherited by their sons.[105] As a result, the generals became the dominant ruling class, surpassing the bureaucracy in power and influence. The officials had little political autonomy and simply carried out the emperor's orders and requests.[106] This system mirrored the one established during the Yuan dynasty, with the ruling class of Mongols and Semu being replaced by families of distinguished military commanders.[107] These families were often connected through kinship ties with each other and with the imperial family.[108]

The administrative structure of the Ming dynasty was modeled after the Yuan model. The Central Secretariat led the civil administration and was headed by two Grand Councilors who were informally known as Prime Ministers. The Secretariat was responsible for six ministries: Personnel, Revenue, Rites, War, Justice, and (Public) Works. The Censorate oversaw the administration, while the Chief Military Commission was in charge of the army, but under later emperors, the civil administration, which was the core of the government, became primarily focused on supporting the army financially and logistically.[109] Initially, the provinces were under the control of generals, with the civil authorities also reporting to them.[104] In the 1370s, the military's influence decreased as ministers were appointed to leadership positions in the provinces.[104] Regional military commanders were then responsible for managing the affairs of hereditary soldiers in the Weisuo system.[104]

The Weisuo system was introduced in 1364 and stabilized in the 1370s. Soldiers under this system were obligated hereditarily to serve, with each family required to provide one member for military service in each generation.[105] The army was self-sufficient thanks to the production of these hereditary soldiers.[105] By 1393, the empire's armed forces consisted of 326 guards and 65 battalions,[105] but after 1368, the army may have been larger than necessary, as the government feared the consequences of widespread demobilization.[105]

In order to limit the influence of eunuchs in the palace, the Emperor initially restricted their number to 100, but he later allowed their number to increase to 400, with the condition that they were not allowed to learn to read, write, or interfere in politics.[110]

The state administration was reformed based on Confucian principles. In February 1371, the Emperor made the decision to hold provincial and county examinations every three years, with the provincial examinations already taking place in March,[111] but in 1377, he cancelled the civil service examinations due to their lack of connection to the quality of the graduates.[112][113] Despite his support for Confucianism, the Emperor had a deep distrust for the official class and did not hesitate to severely punish them for any wrongdoing.[114] After the resumption of examinations in 1384,[113] he went as far as executing the chief examiner when it was revealed that he had only awarded the jinshi degree to applicants from the south.[112]

Every three years, provincial examinations were held, and those who passed were awarded the title of juren. This title was sufficient for starting an official career in the early Ming period, and also qualified individuals for teaching positions in local schools until the end of the dynasty.[115] Following the provincial examinations, metropolitan examinations were held. Upon passing, candidates advanced to the palace examinations, where the Emperor himself read their work. Successful candidates were awarded the rank of jinshi, with a total of 871 individuals granted it during the Hongwu period.[115][xvii]

There were fewer than 8,000 civil servants,[116] with half of them in lower grades (eighth and ninth), not including the approximately 5,000 teachers in government schools.[115] During the early Ming period, the examinations did not produce enough candidates, and positions were often filled based on recommendations and personal connections.[115] The bureaucratic system was still in its early stages, and the introduction of examinations primarily had symbolic significance as a declaration of allegiance to Confucianism.[117]

Local government and taxation

The villages were self-governing communities that resolved internal disputes without interference from officials, as the Hongwu Emperor did not recommend their presence in the countryside. These communities operated based on Confucian morality rather than laws.[106]

Population and land were registered through two interlocking systems: the Yellow Registers, which recorded households and population, and the Fish-Scale Registers, which recorded land parcels, their quality, tax quotas, and ownership. County authorities appointed wealthy individuals as regional tax captains (liangzhang; 糧長) responsible for collecting taxes.[118] In 1371, the lijia system of local self-government was introduced in the Yangtze River basin and gradually expanded throughout the empire.[119][xviii] Regular state expenses, except for land tax, were covered through mandatory services and supplies from the population. In the lijia system, one jia always provided services, and after a year, it was replaced by another. This form of taxation was progressive, unlike the land tax. Large infrastructure projects, such as road and dam construction or canals, were funded through additional ad hoc requisitions.[121]

Taxes were low, with a fixed amount for each region, intended for peasants to pay 3% of their harvest. These taxes were often collected in kind, with the population responsible for delivering goods to state warehouses,[116] but the transportation of these goods, often over long distances of hundreds of kilometers, placed a heavy burden on taxpayers. The cost of transporting grain to Nanjing was three to four times higher than its price, and even six to seven times higher for supplies to the army on the northern border.[122] The Ministry of Revenue was responsible for collecting taxes and benefits from peasants, while the Ministry of Works oversaw artisans.[123] Artisans were required to work in state factories for three months every 2 to 5 years, depending on their profession.[124] The Ministry of War kept records of hereditary soldiers and also collected taxes and benefits from them.[123] As state income and expenditure were managed through orders for the population to deliver specific goods to designated locations, large warehouses were not necessary. However, officials were not always able to effectively direct supplies to the necessary places, leading to local supply crises.[116]

Society

The Hongwu Emperor promoted parsimony and simplicity, aiming to restore a basic agricultural economy with other industries in supporting roles.[116] To preserve social cohesion and the state's economic foundations, he restricted the consumption of the wealthy, fearing that displays of luxury would damage society. Rooted in Confucian morality, the privileged were expected to practice self-restraint, and the Emperor set the example by living with simple food and furnishings.[125] He regarded comfort, luxury, and property as signs of selfish corruption. His orders included replacing flower gardens in his sons’ palaces with vegetable gardens, banning exotic pets in favor of useful animals like cows, and prohibiting rice varieties used for making rice wine. The government also regulated consumption standards for food, clothing, housing, and transportation.[126] These controls extended to everyday life, such as standards for greetings and writing style,[127] restrictions on personal names,[128] and bans on symbols connected to the Emperor's monastic past.[129]

The Emperor believed that providing every man with a field and every woman with a loom would alleviate the people's hardships, but this ideal was not reflected in reality as the wealthy held a disproportionate amount of land and often found ways to avoid paying taxes.[130] In fact, during the last years of the Yuan dynasty, the land tax yield dropped to zero.[131] In response, the Hongwu Emperor confiscated land from the wealthy and redistributed it to the landless. Those who had abandoned their properties during the wars were not entitled to have them returned, but were instead given replacement plots of land on the condition that they personally worked on them.[130] The government punished large landowners and confiscated their land. While Emperor Taizu of Song saw the wealthy as the gateway to prosperity for the entire country, the Hongwu Emperor sought to eliminate the wealthy. As a result of his reforms, there were very few large landowners left.[131]

After ascending to the throne, the Hongwu Emperor resettled 14,300 wealthy families from Zhejiang and the Yingtian area from their estates to Nanjing.[131] He also confiscated the vast properties of Buddhist monasteries, which during the Yuan dynasty owned 3/5 of the land in Shandong province. The government abolished 3,000 Buddhist and Taoist monasteries, and 214,000 Buddhist and 300,000 Taoist monks and nuns returned to secular life. Additionally, each county was limited to one monastery with a maximum of two monks.[132] To address the issue of landlessness, free land was allocated to peasants. In the north, peasants received 15 mu per field and 2 per garden, while in the south, they received 16 mu. Hereditary soldiers were given 50 mu.[132]

In contrast to the attitude towards the wealthy, care for the poor was significantly increased (and by the 16th century, considered standard). The government ordered the establishment of shelters for beggars in each county, and rations of rice, wood, and cloth were guaranteed for other poor individuals. Additionally, octogenarians and older individuals were guaranteed meat and wine. These expenses were covered by the lijia system,[133] which required wealthy families to contribute or face property confiscation.[134]

Agriculture

There were no arable lands available, so farmers who fertilized uncultivated land were exempted from taxes for three years. The government also encouraged refugees and people from densely populated areas to resettle on vacant land in the north, providing various reliefs to resettlers.[135] To increase the labor force, slavery was abolished and the slave trade was banned (only members of the imperial family were allowed to own slaves), the number of monks was reduced, and the buying and selling of free people, including the acceptance of women, children, and concubines as collateral, was prohibited.[135]

In addition to reclaiming abandoned land, the government took measures to restore irrigation systems. The Hongwu Emperor ordered local authorities to report any requests or comments from the population regarding the repair or construction of irrigation structures to the court. In 1394, he issued a special decree for the Ministry of Works to maintain canals and dams in case of drought or heavy rains. He also sent graduates from state schools and technical specialists to oversee flood protection structures throughout the country. By the winter of 1395, a total of 40,987 dams and drainage canals had been constructed across the country.[135]

Currency

Inflation at the end of the Yuan era caused paper money to be abandoned in favor of grain as the primary medium of exchange. In 1361, Zhu Yuanzhang began minting coins, but the small amount produced did not have a significant economic impact. Instead, it served as a symbol of political independence.[136] In the 1360s, the government lacked the power to control the economy, so it allowed old coins to circulate and left price determination to the market.[136]

After China was reunified, officials reported that a shortage of coins hindered circulation. The government proposed reducing the copper content by one-tenth to increase minting,[137] but the Emperor rejected this, and because mining could not meet demand, paper currency (banknotes) was reintroduced in 1375 as the primary medium of exchange, with copper coins secondary. Like in the Yuan dynasty, the government tried to promote paper money by prohibiting precious metals, but unlike Yuan paper, it was not convertible into silver, causing rapid devaluation.[138] Attempts to stabilize the currency by repeatedly stopping and restarting printing only led to overissuance.[xix] In 1390, state income was 20 million guan in notes, while expenses reached 95 million.[139] By 1394, the notes had lost 60% of their value, prompting merchants to use silver instead.[xx] Although the government withdrew coins and again banned silver in 1397,[139] merchants continued valuing goods in silver, using banknotes mainly for payments.[140]

The anti-silver policy can be seen as an attempt to weaken the influence of the wealthy in Jiangnan, who were previously supporters of Zhang Shicheng. The Ming government also imposed high taxes[xxi] on the Jiangnan elites, confiscated their land, and forced them to relocate. The Emperor saw the possession of silver as granting excessive independence to its owners, so he sought to prohibit the exchange of banknotes for silver.[140]

Trade

The Emperor's distrust of the bureaucratic elite was accompanied by a disdainful attitude towards merchants. He viewed weakening the influence of the merchant class and large landowners as a top priority for his government. As part of this effort, he implemented high taxes in and around Suzhou, which was then the commercial and economic hub of China.[112] Additionally, the government forcibly relocated thousands of wealthy families to Nanjing and the southern bank of the Yangtze River.[112][141] To prevent unauthorized business, traveling merchants were required to report their names and cargo to local agents and undergo monthly inspections by the authorities.[142] They were also obligated to store their goods in government warehouses.[143]

Restrictions on population mobility greatly affected merchants. Any journeys longer than 100 li (58 km) were strictly prohibited without official permission.[144] In order to obtain this permission, merchants were required to carry a travel document that contained their personal information such as name, place of residence, name of village head (lizhang; 里長), age, height, occupation, and names of family members. Any discrepancies or irregularities in this document could result in the merchant being sent back home and facing punishment.[143][xxii]

Merchants were subjected to inspections by soldiers along the route, at a ferry terminal, in the street and in their shops. The authorities required inns to provide details about their guests, such as travel destinations and transported goods, while merchants were also required to store their goods in state warehouses and were not allowed to engage in trading without a license. Even when granting merchants a license, authorities would inspect the goods, destination, and price. Intermediaries, or brokers, were strictly prohibited. The government also set fixed prices for most goods, and failure to comply with these prices resulted in punishment.[143] In addition, merchants risked having their goods confiscated and being subjected to flogging for selling poor quality goods.[125]

The Ming dynasty was one of the few dynasties to enforce the system of four occupations (in descending order: officials, peasants, artisans, merchants). Unlike peasants, merchants were excluded from civil service examinations.[xxiii][145] This exclusion also extended to rank-and-file employees of the authorities who dealt with financial matters, as they were seen as potential sources of corruption. As a result, they were not allowed to take examinations that could elevate them to the official class.[146] Despite the government's efforts, the population's interest in trade remained strong. Contemporary authors attributed this to the fact that a successful trade trip could yield more profit than a year's worth of work in the fields.[145]

Foreign relations

The Emperor's strict control over the economy and society created major difficulties in foreign relations.[147] Viewing trade as corrupting, the government banned private foreign trade[125] and enforced a strict sea ban during the Hongwu era. The Ming forbade its citizens to leave the empire, and applied harsh punishments such as death or exile to foreigners and anyone trading with them.[148] Shipbuilding with two or more masts was banned, ships and ports were destroyed or blocked, and the coast was heavily guarded. The goal was to stop all foreign trade, summarized in the phrase "not even a piece of wood should sail across the sea".[149] The ban offered no alternatives and caused more smuggling, and government crackdowns were ineffective. The Yongle Emperor later encouraged trade through the tribute system.[147]

Foreign relations played a crucial role in establishing the legitimacy of Ming rule. The surrounding states expressed their recognition of Ming authority and superiority by paying tribute. As part of this tribute system, foreign delegations received Chinese goods of equivalent value from the Ming state. This was a way for the Ming government to regulate and restrict foreign trade.[147]

In 1368, the Emperor announced his accession to Korea, Đại Việt (present-day northern Vietnam), Champa, and Japan.[150] The following year, Korea, Đại Việt, and Champa sent tribute missions, and in 1370 the Javanese Majapahit did the same. In 1371, Japan, Siam, Cambodia, and the Sumatran Kingdom of Melayu also sent tribute missions, followed by Ryukyu in 1372.[150] From 1369 to 1397, the most frequent missions came from Korea and Ryukyu (20 times each), followed by Champa (19 times), Siam (18 times), and Đại Việt (14 times).[151] Starting in 1370, the government established specialized offices to receive these missions, located in Ningbo, Quanzhou (in Fujian), and Guangzhou.[150] However, four years later, these offices were abolished,[152] resulting in a significant decrease in tributary trade. Nonetheless, it remained substantial, with the Siamese mission bringing 38 tons of aromatic substances in 1392 and the Javanese mission bringing almost 17 tons of pepper in 1382.[150]

Before embarking on any conquests abroad, the Hongwu Emperor made it a priority to stabilize the government in China. As a result, he refused to assist Champa in their war against Đại Việt and instead reprimanded the Viets for their aggression.[150] In 1372, after facing defeats in Mongolia, he cautioned future emperors against the pursuit of conquering glory and advised them to focus on defending China against "northern barbarians".[153] The Ming government recognized the Southern Court in Japan as legitimate, while viewing the Kyoto government as usurpers,[152][111] but they resorted only to harsh correspondence and never to force. This was likely due to the memory of the failed Mongol invasion of Japan.[152]

Changes in the 1380s

The decade of 1371–1380 was a period of consolidation and stability,[154] but in 1380, the Emperor initiated a new wave of reforms, taking direct and personal control, while also intensifying the terror against the elite.[155]

The Emperor's sons

The Emperor chose to give his sons the titles of princes (wang) and assigned them military command on the border to protect the empire.[100] Along with receiving Confucian education, which emphasized moral values, the Emperor's sons also learned about warfare. The Emperor placed great importance on the education of his sons and entrusted it to scholars led by Song Lian and Kong Keren (孔克仁).[156]

The Emperor made the decision to place the princes in charge of the army in order to diminish the influence of the military nobility on the state. The Emperor was highly concerned about potential conspiracies among the generals, a number of whom he executed, as seen in the cases of Hu Weiyong and Lan Yu.[89] His fears were not unfounded, as the threat of conspiracies among the generals was always present. He himself came to power through the betrayal of Guo Zixing's heirs and later faced conspiracies from his subordinates.[xxiv][10]

The most capable military leaders among the princes were Zhu Di and Zhu Gang, later joined by Zhu Fu, Zhu Zhen, Zhu Zhi, and Zhu Bai. Among the literary-minded imperial princes, Zhu Su stood out for his works on Yuan court poetry and medicinal plants, while Zhu Quan was known for his lyrical dramas and encyclopedias on alchemy and pharmacy. Other princes, such as Zhu Zi, Zhu Tan, Zhu Chun, and Zhu Bai, were also comfortable in the company of scholars and skilled in the art of war.[157] However, not all princes behaved properly, and the Emperor often reprimanded six of his sons–Zhu Shuang, Zhu Su, Zhu Fu, Zhu Zi, Zhu Tan, and Zhu Gui–and his great-nephew Zhu Shouqian.[158]

In 1370, the Emperor appointed nine of his oldest sons (after the heir to the throne) as princes.[xxv] Five more were appointed in 1378, and the remaining ten in 1391. Once they reached around twenty years of age, they were sent to their designated regions, with the first being sent in 1378. As they settled into their regions, their importance grew.[160] The most influential of these princes were the second, third, and fourth sons—Zhu Shuang, Zhu Gang, and Zhu Di—who were based in Xi'an, Taiyuan, and Beijing respectively. They were responsible for commanding the armies on the northern frontier.[83] Apart from the princes, other members of the imperial family were excluded from the administration of the country.[160]

Reforms of the central government

The structure of the civil administration, organized according to the Yuan model, partially distanced the Emperor from direct exercise of power and did not satisfy him. In the early 1380s, he proceeded with a radical reorganization of the administrative apparatus, with the primary goal of centralization and increasing the ruler's personal power.[161]

In 1380, Grand Chancellor Hu Weiyong was imprisoned and executed on suspicion of participating in a conspiracy against the Emperor. As a result, the Emperor abolished Hu's position and the entire Central Secretariat,[162][163] forbidding its restoration permanently.[164] The Emperor then placed six ministries directly under his control.[164] He also temporarily abolished the Censorate and divided the unitary Chief Military Commission, governing the armed forces, into five Chief Military Commissions, each controlling a portion of the troops in the capital and a fifth of the regions.[165][166][167] Additionally, twelve guards of the Imperial Guard in the capital were directly subordinate to the Emperor. One of these guards, known as the Embroidered Uniform Guard, acted as the secret police. This resulted in the fragmentation of state authority, which immediately eliminated the possibility of a coup d'état but weakened the government's long-term ability to act.[164]

After the major purge of 1380, smaller processes followed targeting several ministers and deputy ministers, as well as the Emperor's nephew Li Wenzhong and hundreds of less prominent individuals.[168] The executions sparked a wave of protests from officials, who pointed to the demoralization of the state apparatus and the waste of human resources. The Emperor did not punish the critics, but he also did not change his policies.[169]

Domestic and foreign policy

In 1381, the government implemented the lijia throughout the country and introduced the Yellow Registers to revise the population records.[170] Additionally, a census was conducted.[xxvi] As part of this system, tax collection was transferred to the li, resulting in the abolition of regional tax captains in 1382, but they were reinstated three years later. Regional tax captains collected taxes from the heads of the li[172] and delivered them to state granaries. The li were responsible for covering expenses related to transportation, accounting, and supervision.[173]

The campaign against large landowners also targeted the new Ming officials. In 1380, land ownership of ministers and officials was reviewed, followed by a similar review in 1381 for holders of noble titles,[131] including members of the imperial family. These individuals were required to return their acquired lands to the state and were compensated with rice and silk.[132] This resulted in a long-lasting fragmentation of land ownership. Even two centuries later, He Liangjun (何良俊; 1506–1573) observed that there were no large landowners in Suzhou, and no one owned more than ten times the amount of land as a small peasant.[174]

In 1382, the Emperor suffered a significant loss when Empress Ma died. That same year, the newly appointed head of the Court of Judicature and Revision criticized the Emperor's support of Buddhist monks, their privileges at court, and their position in the government. As a result, the Emperor limited their influence. At the same time, there was a growing support for Confucianism, leading to the opening of Confucian temples throughout the empire. These temples had previously been closed in 1369, with the exception of one in Confucius' birthplace.[175] This shift towards Confucianism also resulted in the renewal of civil service examinations in 1384,[155] which only required knowledge of the Four Books and Five Classics. The promotion of Confucianism strengthened the emphasis on moral considerations, rather than just economic factors, in the management of the state.[93]

The 1380s saw a significant increase in foreign policy activity.[155] In 1380 and 1381, the northern border troops launched large-scale expeditions beyond the Great Wall.[155][176] In 1381, the Ming army, led by Fu Youde, quickly conquered Yunnan, but suppressing local uprisings kept Fu's soldiers occupied for several more years. Additionally, a significant number of troops were needed to guard the coast against smugglers and pirates, delaying the offensive in the north until 1387.[177] The campaign into Manchuria in 1387 was ultimately successful, but the commanding general, Feng Sheng, was replaced by Lan Yu. In the 1388 campaign, Lan Yu's army of 200,000 decisively defeated the Mongols at the Songhua River and Buir Lake.[176] The Chinese captured 73,000 Mongol warriors, including the Mongol heir apparent and his younger brother. Mongol khan Tögüs Temür fled, but was assassinated the following year, leading his people to dispute the succession. As a reward, Lan was granted the title of duke, and six of his generals were made marquises.[178] The campaign also resulted in the annexation of the Liaodong Peninsula.[179]

1390s: Succession crisis and death

From 1390 onwards, the armies sent north of the Great Wall were commanded by the Emperor's sons, especially Zhu Di, but also Zhu Shuang, Zhu Gang, and Zhu Fu.[180] A new wave of arrests also began in the early 1390s. In the autumn of 1391, the Emperor's heir, Zhu Biao, went on an inspection trip to Shaanxi, where he was supposed to assess the possibility of moving the capital to Xi'an,[181] but upon his return he fell ill and died in 1392. The sudden death of the heir caused instability in the power system.[160] In response, the Emperor appointed Zhu Biao's son, Zhu Yunwen, as the new heir. In order to ensure a smooth transition of power to the young heir, the Emperor initiated a massive new wave of purges in 1393, starting with the accusation and execution of General Lan Yu. He hoped these purges would dismantle the military nobility.[107]

During the thirty years of the Hongwu Emperor's rule, approximately 100,000 people were killed in political purges.[162][163] The most notable of these purges occurred in 1390, when arrests and executions extended to the entire ruling class.[107] It seems that the Emperor realized that the military hereditary elite was not a reliable source of support for the throne and made the decision to eliminate them.[107] In an attempt to address the issue of extreme wealth disparities, many landowners and merchants were unjustly executed under the false accusation of being associated with treacherous politicians.[131]

However, the power vacuum that resulted was not filled by civil officials, but primarily by the Emperor's sons.[107] Similar to the generals before them, they alternated between serving on the border with the army and holding audiences in the capital.[180] This helped to stabilize the empire during the Hongwu Emperor's lifetime,[180] but after his death, a crisis arose due to the loyalty of the generals and officials being directed towards the emperor as an individual rather than the office.[155]

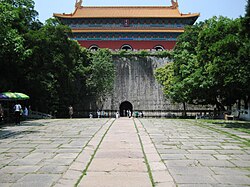

The Hongwu Emperor fell seriously ill in December 1397 and again from 24 May 1398. On 22 June 1398, his condition worsened, and he died on 24 June.[182] He was buried in the Xiao Mausoleum, located on the southern side of Purple Mountain, east of Nanjing.[183]

Assessment

In traditional Chinese historiography, the Hongwu Emperor was revered as a typical founder of a dynasty. He is credited with bringing China out of the chaos of civil war and freeing it from foreign rule. His unification of the country and restoration of order in society laid the groundwork for a prosperous and thriving era under the new dynasty. In recognition of his achievements, his ministers gave him the temple name Taizu, meaning "Grand Progenitor". This perspective was reflected in the official history of the Ming dynasty, known as the History of Ming, which was written during the Qing dynasty.[184]

Modern historians, influenced by a strong aversion towards the dictators of the 20th century, an anti-monarchist mindset, and a tendency to psychoanalyze personalities, often place a heavy emphasis on the despotic nature of the Hongwu Emperor's regime[184] and attribute it to paranoia,[51] or more generally, to some form of mental illness.[185] They primarily view him as a dictator whose irrational actions and paranoia resulted in the loss of countless lives.[184] Other approaches examine him within the context of his time and personal experiences. This perspective highlights the impact of his life experiences on his goals and the methods he employed to achieve them. His impoverished and unstable upbringing is considered a crucial period in which he developed his personal philosophy.[184]

The Hongwu Emperor is widely regarded as one of the most influential and remarkable rulers in Chinese history, regardless of which aspect of his life is emphasized. His reforms had a lasting impact on the Chinese state and society for centuries to come.[49][186] In order to establish a well-ordered and virtuous society, he adopted Zhu Xi's version of Neo-Confucianism as the state ideology, which greatly contributed to its widespread adoption.[187]

The abolition of the Grand Secretariat and the reform of central administrative bodies resulted in the loss of strong representation for officials. This led to a significant increase in the ruler's power and marked a departure from the Song and Yuan empires, where the emperor's authority was limited. Instead, it established a more despotic rule that continued through the Qing dynasty.[188] Alternatively, some argue that the unification of the country under a centralized state with an all-powerful emperor during the Ming dynasty was the culmination of a long process that began with the Qin and Han dynasties.[187]

Chancellors

| In office | Left Grand Councilor | Right Grand Councilor |

|---|---|---|

| 1368–1371 | Li Shanchang | Xu Da |

| 1371 | Xu Da | Wang Guangyang |

| 1371–1373 | Vacant | |

| 1373–1377 | Hu Weiyong | |

| 1377–1380 | Hu Weiyong | Wang Guangyang |

Family

The Hongwu Emperor had many Korean and Mongolian women among his concubines along with Empress Ma and had 16 daughters and 26 sons by them.[190]

- Empress Xiaocigao of the Ma clan[191]

- Zhu Biao, Crown Prince Yiwen (1355–1392), first son[192]

- Zhu Shuang, Prince Min of Qin (1356–1395), second son[193]

- Zhu Gang, Prince Gong of Jin (1358–1398), third son[194]

- Zhu Di, Prince of Yan, later the Yongle Emperor (1360–1424), fourth son[195]

- Zhu Su, Prince Ding of Zhou (1361–1425), fifth son[196]

- Princess Ningguo (寧國公主; 1364–1434), second daughter. Married Mei Yin (d. 1405), nephew of Mei Sizu, Marquis of Runan, in 1378.[197]

- Princess Anqing (安慶公主), fourth daughter. Married Ouyang Lun (歐陽倫; d. 1397) in 1381.[198]

- Noble Consort Chengmu of the Sun clan (1342–1374)[199]

- Princess Lin'an (臨安公主; d. 1421), personal name Jingjing (鏡靜), first daughter. Married Li Qi (李祺; d. 1403), the eldest son of Li Shanchang, Duke of Han, in 1376.[200]

- Princess Huaiqing (懷慶公主), sixth daughter. Married Wang Ning (王寧), Marquis of Yongchun (永春侯) in 1382.[201]

- Tenth daughter[202]

- Thirteenth daughter[203]

- Noble Consort (貴妃) of the Yong clan (永氏)[204]

- Noble Consort (貴妃) of the Wang clan (汪氏)[204]

- Noble Consort (貴妃) of the Zhao clan (趙氏)[204]

- Consort Shu (淑妃) of the Li clan (李氏)[206]

- Consort Ning (寧妃) of the Guo clan (郭氏)[207]

- Princess Runing (汝寧公主), fifth daughter. Married Lu Xian (陸賢), son of Lu Zhongheng, Marquis of Ji'an, in 1382.[201]

- Princess Daming (大名公主; d. 1426), seventh daughter. Married Li Jian (李堅; d. 1401) in 1382.[201]

- Zhu Tan (朱檀), Prince Huang of Lu (魯荒王; 1370–1390), tenth son[208]

- Consort Zhaojingchong (昭敬充妃) of the Hu clan (胡氏)[204]

- Zhu Zhen, Prince Zhao of Chu (1364–1424), sixth son[209]

- Consort Ding (定妃) of the Da clan (達氏; d. 1390)[210]

- Zhu Fu (朱榑), Prince Gong of Qi (齊恭王; 1364–1428), seventh son[211]

- Zhu Zi (朱梓), Prince of Tan (潭王; 1369–1390), eighth son[212]

- Consort An (安妃) of the Zheng clan (鄭氏)[213]

- Princess Fuqing (福清公主; d. 1417), eighth daughter. Married Zhang Lin (張麟), son of Zhang Long, Marquis of Fengxiang, in 1385.[214]

- Consort Hui (惠妃) of the Guo clan (郭氏)[215]

- Zhu Chun (朱椿), Prince Xian of Shu (蜀獻王); 1371–1423), 11th son[216]

- Zhu Gui, Prince Jian of Dai (1374–1446), 13th son[217]

- Princess Zhenyi of Yongjia (永嘉貞懿公主; 1376–1455), 12th daughter. Married Guo Zhen (郭鎮), son of Guo Ying, Marquis of Wuding, in 1389.[218][215]

- Zhu Hui (朱橞), Prince of Gu (谷王; 1379–1428), 19th son[219]

- Princess Ruyang (汝陽公主), 15th daughter. Married Xie Da (謝達) in 1394.[203]

- Consort Shun (順妃) of the Hu clan (胡氏)[215]

- Zhu Bai (朱柏), Prince Xian of Xiang (湘獻王; 1371–1399), 12th son[220]

- Consort Xian (賢妃) of the Li clan (李氏)[221]

- Zhu Jing, Prince Ding of Tang (唐定王 朱桱; 1386–1415), 23rd son[222]

- Consort Hui, of the Liu clan (惠妃 劉氏)[223]

- Zhu Dong (朱棟), Prince Jing of Ying (郢靖王; 1388–1414), 24th son[224]

- Consort Li (葛氏) of the Ge clan (麗妃)[223]

- Consort Zhuangjinganronghui (莊靖安榮惠妃) of the Cui clan (崔氏)[226]

- Consort (妃) of the Han clan (韓氏)[213]

- Consort (妃) of the Yu clan (余氏)[228]

- Zhu Zhan (朱㮵), Prince Jing of Qing (慶靖王; 1378–1438), 16th son[229]

- Consort (妃) of the Yang clan (楊氏)[230]

- Consort (妃) of the Zhou clan (周氏)[230]

- Consort (妃; d. 1398) of the Weng clan (翁氏)[234]

- Beauty (美人) of the Zhang clan (張氏), personal name Xuanmiao (玄妙)[235]

- Princess Baoqing (寶慶公主; 1395–1433), 16th daughter. Married Zhao Hui (趙輝) in 1413.[203]

- Beauty (美人) of the Qu clan (屈氏)[235]

- Lady Gao (郜氏)[230]

- Zhu Ying (朱楧), Prince Zhuang of Su (肅莊王; 1376–1420), 14th son[236]

- Unknown

- Princess Chongning (崇寧公主), third daughter. Married Niu Cheng (牛城) in 1384.[237]

- Zhu Qi (朱杞), Prince of Zhao (趙王; 1369–1371), ninth son[208]

- Princess Shouchun (壽春公主; d. 1388), ninth daughter. Married Fu Zhong (傅忠), son of Fu Youde, Duke of Ying, in 1386.[202]

- Princess Nankang (南康公主; d. 1438), personal name Yuhua (玉華), 11th daughter. Married Hu Guan (胡觀), son of Hu Hai, Marquis of Dongchuan, in 1388.[202]

- Zhu Ying (朱楹), Prince Hui of An (安惠王; 1383–1417), 22nd son[222]

See also

- Chinese emperors family tree (late)

- Huang-Ming Zuxun, the "Ancestral Instructions" written by the Hongwu Emperor to guide his descendants

- Ming Xiaoling Mausoleum

- Ming–Tibet relations

- Ming dynasty in Inner Asia

- Hongwu Tongbao

Notes

- ^ Zhu Yuanzhang had already been in control of Nanjing since 1356, and was conferred the title of "Duke of Wu" (吳國公) by the rebel leader Han Lin'er (韓林兒) in 1361. He started autonomous rule as the self-proclaimed "King of Wu" on 4 February 1364. He was proclaimed emperor on 23 January 1368 and established the Ming dynasty on that same day.

- ^ Chinese: 朱重八; pinyin: Zhū Chóngbā[2]

- ^ a b 21 October 1328 is the Julian calendar equivalent of the 18th day of the 9th month of the Tianli (天曆) regnal period of the Yuan dynasty. When calculated using the Proleptic Gregorian calendar, the date is 29 October.[3][4]

- ^ simplified Chinese: 朱兴宗; traditional Chinese: 朱興宗; pinyin: Zhū Xìngzōng[2]

- ^ Chinese: 朱元璋; pinyin: Zhū Yuánzhāng[8]

- ^ simplified Chinese: 吴; traditional Chinese: 吳; pinyin: Wú[8]

- ^ Chinese: 洪武; pinyin: Hóngwǔ[8]

- ^ simplified Chinese: 钦明启运俊德成功统天大孝高皇帝; traditional Chinese: 欽明啟運俊德成功統天大孝高皇帝 (conferred by the Jianwen Emperor in 1398)[8]

- ^ simplified Chinese: 圣神文武钦明启运俊德成功统天大孝高皇帝; traditional Chinese: 聖神文武欽明啟運俊德成功統天大孝高皇帝 (conferred by the Yongle Emperor in 1403)[8]

- ^ simplified Chinese: 开天行道肇纪立极大圣至神仁文义武俊德成功高皇帝; traditional Chinese: 開天行道肇紀立極大聖至神仁文義武俊德成功高皇帝 (changed by the Jiajing Emperor in 1538)[8]

- ^ Chinese: 太祖; pinyin: Tàizǔ[8]

- ^ Courtesy name: Guorui (simplified Chinese: 国瑞; traditional Chinese: 國瑞; pinyin: Guóruì)[8]

- ^ a b c d Wu is a geographical term derived from the ancient state of Wu, which refers to the lower reaches of the Yangtze River. The use of the titles Duke of Wu (from 1361; from 1364 King of Wu) by Zhu Yuanzhang and King of Wu (from 1363) by Zhang Shicheng reflected their rivalry and denial of each other's legitimacy.

- ^ He conquered Zhenjiang, Changzhou, Changxing, Jiangyin, Changshu, and Yangzhou.[38]

- ^ After the Jinhua Prefecture in Zhejiang, where they were concentrated.[47]

- ^ In 1370, 34 distinguished generals were appointed as dukes and marquises (hou). Out of these, 6 dukes and 14 marquises were among the original 24 companions of the Hongwu Emperor, 5 marquises joined in 1355 during the crossing of the Yangtze River (they belonged to the rebels from Lake Chao who laid the foundation for Zhu's fleet), and 9 marquises were former enemy commanders who surrendered. By 1380, the Emperor had appointed an additional 14 marquises from the aforementioned groups. They were all granted land and income from the state treasury, but not as fiefs.[104]

- ^ In 1371, the rank of jinshi was awarded to 120 people. In 1385, it was awarded to 472 people, which was an exceptionally high number. Thereafter, the number of recipients was 97 in 1388, 31 in 1391, 100 in 1394, and 51 in 1397.[115]

- ^ A li contained 110 households, consisting of ten jia with ten households each, as well as the ten leading families who were typically the wealthiest. These families were responsible for appointing headmen to collect taxes and oversee service labor, as well as providing services such as education.[120]

- ^ The mints were closed in the years 1375–1377 and again in 1387–1389. The printing of money was interrupted in the years 1384–1389 and stopped again in 1391.[139]

- ^ In 1390, one guan was worth 250 copper coins in Jiangnan markets, a mere one-fourth of its nominal value, but by 1394, its value had dropped to 160 copper coins.[139]

- ^ Five prefectures of Zhejiang contributed 1/4 of the total taxes of the empire.[140]

- ^ A century later, the prominent scholar Zhu Yunming (1461–1527) recalled how his grandfather was sentenced to death after losing his travel documents, but was granted amnesty by the Emperor just minutes before his execution.[143]

- ^ For example, among the 110 jinshi in 1400, 83 were from peasant families, 16 were from military families, and only 6 were from scholarly families, with none from merchant families. Discrimination against merchants persisted for centuries. In 1544, none of the 312 new jinshi came from a merchant family.[145]

- ^ For example, the rebellion of Shao Rong (邵榮) in 1362.[10]

- ^ At the same time, the Emperor named his great-nephew Zhu Shouqian (1364–1392) the Prince of Jingjiang.[159]

- ^ During the census of 1381, a total of 59,873,305 people were counted, but due to the fact that the census was primarily used to determine tax obligations, many citizens deliberately avoided being counted. As a result, in 1391, only 56,774,561 people were officially recorded. The government, believing that the population must have increased during the ten years of peace and prosperity, ordered a recount in 1393. This time, the result was 60,545,812, though the actual population was likely closer to 75 million.[171]

References

Citations

- ^ a b Goodrich & Fang (1976), pp. 258–259.

- ^ a b c Hu (2001), p. 16.

- ^ Teng (1976), p. 381.

- ^ Mote (1988), p. 11.

- ^ Tsai (2001), p. 28.

- ^ Becker (1998), p. 131.

- ^ Becker (2007), p. 167.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Moule (1957), p. 106.

- ^ a b Goodrich & Fang (1976), p. xxi.

- ^ a b c d Dreyer (1982), p. 67.

- ^ a b c Dreyer (1982), p. 68.

- ^ Farmer (1995), p. 8.

- ^ "Ming dynasty | Dates, Achievements, Culture, & Facts | Britannica". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 23 January 2025.

- ^ Theobald, Ulrich (19 March 2016). "The Southern Ming Dynasty (www.chinaknowledge.de)". chinaknowledge.de. Retrieved 23 January 2025.

- ^ Dreyer (1982), pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b Mote (1988), p. 44.

- ^ Chan, David B. "Hongwu". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ^ Zhou (2017), p. 37.

- ^ a b Mote (2003), pp. 543–545.

- ^ Mote (2003), pp. 545–546.

- ^ a b Farmer (1995), p. 18.

- ^ a b Gascoigne (2003), p. 150.

- ^ Farmer (1995), pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dreyer (1988), p. 62.

- ^ Mote (2003), p. 548.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), pp. 190–191.

- ^ Mote (2003), p. 549.

- ^ Mote (2003), p. 550.

- ^ Dreyer (1988), p. 63.

- ^ a b c Dreyer (1988), p. 68.

- ^ Dreyer (1988), pp. 68–69.

- ^ a b Dreyer (1988), p. 69.

- ^ Wu (1980), p. 61.

- ^ a b c Dreyer (1988), p. 70.

- ^ Mote (2003), p. 552.

- ^ a b Mote (1988), p. 52.

- ^ Farmer (1995), p. 23.

- ^ a b c d Dreyer (1988), p. 71.

- ^ a b c d e Dreyer (1988), p. 72.

- ^ Mote (1988), p. 53.

- ^ Mote (1988), pp. 52–53.

- ^ Wu (1980), p. 79.

- ^ Farmer (1995), pp. 5–6.

- ^ Wu (1980), p. 72.

- ^ Mote (1988), p. 48.

- ^ a b Mote (1988), p. 54.

- ^ a b Dardess (1983), p. 582.

- ^ Theobald, Ulrich. "Chinese History - Yuan Dynasty 元朝 (1206/79-1368) event history. The End of Mongol Rule". Chinaknowledge - a universal guide for China studies. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^ a b Farmer (1995), p. 7.

- ^ Dreyer (1982), p. 123.

- ^ a b Fairbank & Goldman (2006), pp. 128–129.

- ^ Dreyer (1988), p. 77.

- ^ Dreyer (1988), p. 78.

- ^ Dreyer (1988), p. 79.

- ^ Dreyer (1988), p. 82.

- ^ a b Mote (1988), p. 51.

- ^ a b c Dreyer (1988), p. 83.

- ^ Dreyer (1988), p. 84.

- ^ Dreyer (1988), pp. 85–86.

- ^ Dreyer (1988), pp. 89–90.

- ^ Dreyer (1988), p. 89.

- ^ Dreyer (1988), pp. 90–91.

- ^ Wakeman (1985), p. 25.

- ^ Dreyer (1988), p. 91.

- ^ a b Dreyer (1988), pp. 91–92.

- ^ a b Mote (1988), p. 55.

- ^ Dreyer (1988), p. 92.

- ^ Dreyer (1988), pp. 92–93.

- ^ Dreyer (1982), pp. 69–70.

- ^ a b Langlois (1988), p. 111.

- ^ Dreyer (1988), pp. 96–97.

- ^ a b Dreyer (1988), p. 97.

- ^ Dreyer (1988), p. 96.

- ^ Langlois (1988), p. 112.

- ^ Langlois (1988), pp. 112–113.

- ^ Langlois (1988), p. 113.

- ^ Dreyer (1988), p. 98.

- ^ Dreyer (1982), p. 71.

- ^ Langlois (1988), p. 117.

- ^ Dreyer (1988), pp. 99–100.

- ^ Dreyer (1982), p. 72.

- ^ Langlois (1988), p. 119.

- ^ a b c Langlois (1988), p. 120.

- ^ a b Dreyer (1982), p. 73.

- ^ a b Dreyer (1982), p. 74.

- ^ Langlois (1988), p. 144–146.

- ^ a b Dreyer (1982), p. 75.

- ^ Dreyer (1988), p. 103.

- ^ a b Dreyer (1982), p. 103.

- ^ Brook (1998), p. vii.

- ^ Farmer (1995), p. 5.

- ^ Brook (1998), pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b Li (2010), p. 24.

- ^ Farmer (1995), p. 10.

- ^ Langlois (1988), p. 156.

- ^ Farmer (1995), p. 15.

- ^ Andrew & Rapp (2000), p. 25.

- ^ Brook (1998), p. 22.

- ^ Langlois (1988), p. 114.

- ^ a b c Langlois (1988), p. 118.

- ^ Langlois (1988), p. 124.

- ^ Hucker (1988), p. 14.

- ^ a b Langlois (1988), p. 107.

- ^ a b c d Dreyer (1988), p. 105.

- ^ a b c d e Dreyer (1988), p. 104.

- ^ a b Huang (1998), p. 106.

- ^ a b c d e Dreyer (1982), p. 147.

- ^ Chan (2007), p. 53.

- ^ Dreyer (1982), p. 11.

- ^ Tsai (1996), p. 13.

- ^ a b Langlois (1988), p. 127.

- ^ a b c d Ebrey (1999), p. 192.

- ^ a b Hucker (1958), p. 13.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), pp. 191–192.

- ^ a b c d e Dreyer (1982), p. 135.

- ^ a b c d Huang (1998), p. 107.

- ^ Dreyer (1982), p. 98.

- ^ Dreyer (1988), p. 123.

- ^ Brook (1998), pp. 23–24.

- ^ Littrup (1977), pp. 40–41.

- ^ Huang (1998), p. 134.

- ^ Li (2007), p. 121.

- ^ a b Theobald, Ulrich. "Chinese History - Ming Dynasty 明朝 (1368-1644). Economy". Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ Li (2010), p. 47.

- ^ a b c Li (2010), p. 38.

- ^ Li (2010), p. 39.

- ^ Brook (1998), pp. 31–32.

- ^ Wu (1980), p. 222.

- ^ Wu (1980), p. 217.

- ^ a b Li (2010), p. 28.

- ^ a b c d e Li (2010), p. 29.

- ^ a b c Li (2010), p. 30.

- ^ Li (2010), p. 32.

- ^ Li (2010), p. 33.

- ^ a b c Shang (1959), pp. 403–412.

- ^ a b Von Glahn (1996), p. 70.

- ^ Von Glahn (1996), pp. 70–71.

- ^ Von Glahn (1996), p. 71.

- ^ a b c d Von Glahn (1996), p. 72.

- ^ a b c Von Glahn (1996), p. 73.

- ^ Brook (1998), p. 29.

- ^ Brook (1998), p. 67.

- ^ a b c d Li (2010), p. 37.

- ^ Brook (1998), p. 19.

- ^ a b c Li (2010), p. 35.

- ^ Li (2010), p. 37l6.

- ^ a b c Dreyer (1982), p. 115.

- ^ Li (2010), p. 3.

- ^ Li (2010), p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e Dreyer (1982), p. 117.

- ^ Dreyer (1982), p. 116.

- ^ a b c Dreyer (1982), p. 120.

- ^ Chase (2003), p. 42.

- ^ Langlois (1988), p. 125.

- ^ a b c d e Dreyer (1982), p. 107.

- ^ Chan (2007), pp. 51–52.

- ^ Chan (2007), p. 54.

- ^ Chan (2007), pp. 54–55.

- ^ Chan (2007), p. 48.

- ^ a b c Dreyer (1982), p. 148.

- ^ Rybakov (1999), p. 528.

- ^ a b Ebrey (1999), pp. 192–193.

- ^ a b Fairbank & Goldman (2006), p. 130.

- ^ a b c Dreyer (1982), p. 105.

- ^ Rybakov (1999), p. 529.

- ^ Hucker (1958), p. 28.

- ^ Chang (2007), p. 15.

- ^ Langlois (1988), pp. 149–151.

- ^ Langlois (1988), pp. 150, 155–156.

- ^ Dreyer (1982), p. 125.

- ^ Brook (1998), p. 28.

- ^ Dreyer (1982), p. 126.

- ^ Huang (1998), p. 135.

- ^ Li (2010), pp. 30–31.

- ^ Langlois (1988), p. 146.

- ^ a b Wakeman (1985), p. 31.

- ^ Dreyer (1982), p. 140.

- ^ Dreyer (1982), p. 143.

- ^ Kavalski (2009), p. 23.

- ^ a b c Dreyer (1982), p. 149.

- ^ Goodrich & Fang (1976), pp. 346–347.

- ^ Langlois (1988), p. 181.

- ^ Teng (1976), p. 391.

- ^ a b c d Dreyer (1982), p. 152.

- ^ Ebrey (2009), p. 223.

- ^ Britannica Educational Publishing (2010), p. 193.

- ^ a b Farmer (1995), p. 17.

- ^ Dreyer (1982), p. 106.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 109, pp. 3306–3309.

- ^ Chan (2007), pp. 45–103.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 113, p. 3505.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 115, p. 3549.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 116, pp. 3559–3560.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 116, pp. 3559, 3562.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 5, p. 69.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 116, pp. 3559, 3565–3566.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 121, pp. 3663–3664.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 121, pp. 3664–3665.

- ^ Wong (1997), p. 4.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 121, pp. 3662–3663.

- ^ a b c History of Ming, vol. 121, p. 3665.

- ^ a b c History of Ming, vol. 121, p. 3666.

- ^ a b c d History of Ming, vol. 121, p. 3667.

- ^ a b c d Wong (1997), p. 7.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 116, p. 3559; vol. 118, p. 3606.

- ^ Wong (1997), p. 13.

- ^ Wong (1997), p. 8.

- ^ a b History of Ming, vol. 116, pp. 3559, 3575.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 116, pp. 3559, 3570.

- ^ Wong (1997), p. 11.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 116, pp. 3559, 3573–3574.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 116, pp. 3559, 3574.

- ^ a b Wong (1997), p. 18.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 121, pp. 3665–3666.

- ^ a b c Wong (1997), p. 10.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 116, p. 3559; vol. 117, pp. 3579–3580.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 116, p. 3559; vol. 117, pp. 3581–3582.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 121, pp. 3666–3667.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 116, p. 3559; vol. 118, pp. 3603–3604.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 116, p. 3559; vol. 117, p. 3581.

- ^ Wong (1997), p. 16.

- ^ a b History of Ming, vol. 116, p. 3559; vol. 118, p. 3607.

- ^ a b Wong (1997), p. 17.

- ^ a b History of Ming, vol. 116, p. 3559; vol. 118, p. 3610.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 116, p. 3559; vol. 118, p. 3612.

- ^ Wong (1997), p. 22.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 116, p. 3559; vol. 117, pp. 3586–3587.

- ^ Wong (1997), p. 19.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 116, p. 3559; vol. 117, pp. 3588–3589.

- ^ a b c Wong (1997), p. 20.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 116, p. 3559; vol. 117, pp. 3591–3593.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 116, p. 3559; vol. 118, p. 3602.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 116, p. 3559; vol. 118, p. 3604.

- ^ Wong (1997), p. 23.

- ^ a b Wong (1997), p. 21.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 116, p. 3559; vol. 117, p. 3585.

- ^ History of Ming, vol. 121, p. 3664.

Works cited

- Andrew, Anita N; Rapp, John A (2000). Autocracy and China's Rebel Founding Emperors: Comparing Chairman Mao and Ming Taizu. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc. ISBN 0-8476-9580-8.

- Brook, Timothy (1998). The Confusions of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming China. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22154-0.

- Becker, Jasper (1998). Hungry Ghosts: Mao's Secret Famine (illustrated, reprint ed.). Macmillan. ISBN 0805056688.

- Becker, Jasper (2007). Dragon Rising: An Inside Look at China Today. National Geographic Books. ISBN 978-1426202100.

- Chan, Hok-lam (2007). "Ming Taizu's Problem with His Sons: Prince Qin's Criminality and Early-Ming Politics" (PDF). Asia Major. 20 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

- Chase, Kenneth (2003). Firearms: a global history to 1700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521822742.

- Chang, Michael G (2007). A Court on Horseback: Imperial Touring & the Construction of Qing Rule, 1680–1785. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02454-0.

- Dreyer, Edward L. (1982). Early Ming China: A Political History. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1105-4.

- Dreyer, Edward L (1988). "Military origins of Ming China". In Mote, Frederick W.; Twitchett, Denis C (eds.). The Cambridge History of China Volume 7: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 58–106. ISBN 0521243327.

- Dardess, John W (1983). Confucianism and autocracy: professional elites in the founding of the Ming Dynasty. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520047334.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China (Cambridge Illustrated Histories ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 052166991X.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B (2009). Pre-modern East Asia: to 1800: a cultural, social, and political history (2nd ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 9780547005393.

- Farmer, Edward L (1995). Zhu Yuanzhang and Early Ming Legislation: The Reordering of Chinese Society Following the Era of Mongol Rule. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004103917.

- Fairbank, John King; Goldman, Merle (2006). China: A New History (2nd ed.). Cambridge (Massachusetts): Belknap Press. ISBN 0674018281.

- Goodrich, L. Carrington; Fang, Chaoying, eds. (1976). Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368–1644. Vol 1: A–L. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-03801-1.

- Teng, Ssu-yü. "CHU Yüan-chang 朱元璋 (T. 國瑞)". In Goodrich & Fang (1976), pp. 381–392.

- Gascoigne, Bamber (2003). The Dynasties of China: A History. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 0786712198.