Anglo-Saxon London

51°30′45″N 00°07′21″W / 51.51250°N 0.12250°W

| Anglo-Saxon London | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| c.450–1066 | |||

| |||

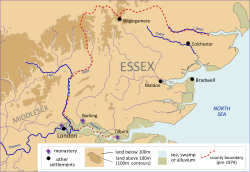

London and the surrounding area, showing major settlements | |||

| Leader(s) | Alfred the Great, Ethelred the Unready, Sweyn Forkbeard, Cnut, Edward the Confessor | ||

| History of London |

|---|

| See also |

|

|

The Anglo-Saxon period of the history of London dates from the end of the Roman period in the 5th century to the beginning of the Norman period in 1066.

Romano-British Londinium was abandoned by the late 5th century, although the London Wall remained intact. There was an Anglo-Saxon settlement by the early 7th century, called Lundenwic, about one mile west of Londinium, to the north of the present Strand. Lundenwic came under direct Mercian control in about 670. After the death of Offa of Mercia in 796, it was disputed between Mercia and Wessex.

Viking invasions became frequent from the 830s, and a Viking army is believed to have camped in the old Roman walls during the winter of 871. Alfred the Great reestablished English control of London in 886, and renewed its fortifications. The old Roman walls were repaired and the defensive ditch was recut, and the old Roman city became the main site of population. The city now became known as Lundenburh, marking the beginning of the history of the City of London. Sweyn Forkbeard attacked London unsuccessfully in 996 and 1013, but his son Cnut the Great finally gained control of London, and all of England, in 1016.

Edward the Confessor became king in 1042. He built Westminster Abbey, the first large Romanesque church in England, consecrated in 1065, and the first Palace of Westminster. These were located just up-river from the city. Edward's death led to a succession crisis, and ultimately the Norman invasion of England.

Lundenwic

In the first half of the 5th century, Roman oversight in London collapsed, leaving the Romanised Britons to look after themselves. By 457, the city appears to have become almost completely abandoned.[1] There is no evidence of anyone living within the city walls for the next 200 years.[2]

Over the next few centuries, settlers arrived from modern-day Germany, the Netherlands and Denmark, who are now referred to as "Anglo-Saxons".[3] Rather than occupy the abandoned, overgrown Roman city, Anglo-Saxons at first preferred to settle outside the walls, only venturing inside to scavenge or explore. One Saxon poet called the Roman ruins "the work of giants".[4] Rather than continuing Romano-British culture, Anglo-Saxons introduced their own building styles, pottery, language, place names and religion.[5] Cemeteries from this early Anglo-Saxon period have been found at Mitcham, Greenwich, Croydon, and Hanwell in Ealing.[5]

By the 670s they had developed the port town of Lundenwic in the area of Covent Garden, taking its name from the old Roman name Londinium and adding the Old English suffix wic or "trading town".[6] Excavations in 1985 and 2005 have uncovered an extensive Anglo-Saxon settlement that dates back to the 7th century.[7][8] The excavations show that the settlement stretched along what is now the Strand (i.e. "the beach").[9] In the early 8th century, Lundenwic was described by the Venerable Bede as "a mart of many peoples coming by land and sea".[9]

By about 600, Anglo-Saxon England had become divided into a number of small kingdoms within what eventually became known as the Heptarchy. Although Bede, writing in the 730s referred to London as the capital of the Kingdom of Essex, it was a border town between three more powerful kingdoms; Mercia, Kent and Wessex, evidence from coins and documents suggests that the Midland kingdom of Mercia dominated London from around 670 until 870, especially during the long reign of Offa. Following Offa's death in 796, supremacy over London was disputed between Mercia and Wessex.[10]

Reconversion to Christianity

In 597, Pope Gregory the Great began the reconversion of southern Britain to Christianity. He sent Augustine of Canterbury to build upon the goodwill of Æthelberht of Kent, and London received Mellitus, its first post-Roman Bishop of London in 601.[9] Mellitus founded the first cathedral of St Paul towards the western end of the old walled city. This first attempt at converting London to Christianity was however short-lived, as Mellitus was driven out of London by pagans following Æthelberht's death in 616.[11]

The bishopric of London was re-established for good in 675, when the Archbishop of Canterbury, Theodore of Tarsus, installed Earconwald as bishop. Although evidence of Christian activity in 7th century London is thin, by the 8th century it had become a major Christian city.[11]

Viking attacks

London suffered attacks from Vikings, which became increasingly common from around 830 onwards. It was attacked in 842 in a raid that was described by a chronicler as "the great slaughter". In 851, another raiding party, reputedly involving 350 ships, came to plunder the city.

In 865, the Viking Great Heathen Army launched a large scale invasion of the small kingdom of East Anglia. They overran East Anglia, Mercia and Northumbria and came close to controlling most of Anglo-Saxon England. By 871 they had reached London and they are believed to have camped within the old Roman walls during the winter of that year.[9]

In 878, West Saxon forces led by Alfred the Great defeated the Vikings at the Battle of Ethandun and forced their leader Guthrum to sue for peace. The Treaty of Wedmore and the later Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum divided England and created the Danish-controlled Danelaw.

Lundenburh

English rule in London was restored by 886.[9] Alfred quickly set about establishing fortified towns or burhs across southern England to improve his kingdom's defences: London was no exception. Within ten years, the settlement within the old Roman walls was re-established, now known as Lundenburh, meaning "Fortress London".[12] The old Roman walls were repaired and the defensive ditch was re-cut. These changes effectively marked the beginning of the present City of London, the boundaries of which are still to some extent defined by its ancient city walls.[13] The Roman road system within the walls had been almost completely erased by overgrowth and time, and so new roads were built which much more closely correspond with London's modern street plan. To this day, London place names are almost all Anglo-Saxon.[2]

As the focus of Lundenburh was moved back to within the Roman walls, the original Lundenwic was largely abandoned and in time gained the name of Ealdwic, 'old settlement', a name which survives today as Aldwych.[11]

10th century London

Alfred appointed his son-in-law Earl Æthelred of Mercia, the heir to the destroyed kingdom of Mercia, as Governor of London and established two defended Boroughs to defend the bridge, which was probably rebuilt at this time. The southern end of the bridge was established as the Southwark or Suthringa Geworc ('defensive work of the men of Surrey'). From this point, the city of London began to develop its own unique local government.

After Æthelred's death, London came under the direct control of English kings. Alfred's son Edward the Elder won back much land from Danish control. By the early 10th century, London had become an important commercial centre. Although the political centre of England was Winchester, London was becoming increasingly important. Æthelstan held many royal councils in London and issued laws from there. Æthelred the Unready favoured London as his capital,[citation needed] and issued his Laws of London from there in 978.

The Vikings' return

From 994, during the reign of Æthelred, Vikings resumed their raids, led by Sweyn Forkbeard of Denmark. In 1013, London was captured and Æthelred was forced to flee abroad. The next year, Æthelred returned with his ally the Norwegian king Olaf and reclaimed London.[9]

Following Æthelred's death on 23 April 1016, his son Edmund Ironside was declared king. Sweyn's son Cnut the Great continued the attacks, harrying Warwickshire and pushing northwards across eastern Mercia in early 1016. By the end of the year Cnut was left as king of all of England. His coronation was in London, at Christmas, with recognition by the nobility in January the next year at Oxford.[14]

Cnut was succeeded briefly by his sons, Harold Harefoot and Harthacnut, after which the Saxon line was restored when Edward the Confessor became king in 1042.

Edward the Confessor and the Norman invasion

Following Harthacnut's death on 8 June 1042, Godwin, the most powerful of the English earls, supported Edward, who succeeded to the throne. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes the popularity he enjoyed at his accession — "before he [Harthacnut] was buried, all the people chose Edward as king in London."[15]

In 1043, Robert of Jumièges became Bishop of London. According to the Vita Ædwardi Regis, he became "always the most powerful confidential adviser to the king".[16] When Edward appointed Robert as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1051, he chose the leading craftsman Spearhafoc to replace Robert as bishop of London, but he was never consecrated.

West of London on Thorney Island in the Thames, there had been an abbey dedicated to St Peter for centuries, but in 1051 Edward the Confessor began to expand this church into what is now known as Westminster Abbey. He is considered its founder and is buried inside. It was consecrated on 28 December 1065.[9] The next year, William of Normandy invaded England, becoming William I, and ending the Saxon period in London.

The average height for Londoners reached a pre-20th century peak[when?], with the male average at 5 feet 8 inches (173 cm) and the female average at 5 feet 41⁄4 inches (163cm).[17]

By 1066, London may have had a population of around 20,000.[18]

References

- ^ Clark, John (1989). Saxon and Norman London. London: Museum of London. pp. 5–6. ISBN 0112904580.

- ^ a b Naismith 2019, p. 42.

- ^ Clark 1989, p. 6.

- ^ Clark 1989, p. 8.

- ^ a b Clark 1989, p. 7.

- ^ Killock 2019, p. 135.

- ^ Patrick Ottaway. Archaeology in British Towns: From the Emperor Claudius to the Black Death.

- ^ Origins of Anglo-Saxon London Archived October 26, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g Richardson, John (2000). The Annals of London: A Year-By-Year Record of a Thousand Years of History. University of California Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-520-22795-8.

- ^ Inwood 1998, pp. 37–38.

- ^ a b c Inwood 1998, pp. 36.

- ^ Naismith 2019, p. 3.

- ^ Inwood 1998, pp. 38–41.

- ^ Frank Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, 3rd ed. Oxford: Clarendon, 1971, ISBN 9780198217169, p. 399.

- ^ Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (MS E) s.a. 1041 (1042), tr. Michael Swanton.

- ^ Van Houts, p. 69. Richard Gem, 'Craftsmen and Administrators in the Building of the Abbey', p. 171. Both in Mortimer ed., Edward the Confessor. Robert of Jumièges is usually described as Norman, but his origin is unknown, possibly Frankish (Van Houts, p. 70).

- ^ Werner, Alex (1998). London Bodies. London: Museum of London. p. 108. ISBN 090481890X.

- ^ Naismith 2019, p. 9.

Sources

- Billings, Malcolm (1994), London: a companion to its history and archaeology, ISBN 1-85626-153-0

- Inwood, Stephen (1998). A History of London. Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-67153-8.

- Killock, Douglas (2019). "London's Middle Saxon Waterfront: excavations at the Adelphi Building". Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society. 70. Museum of London: 129–65. ISBN 978-0-903290-75-3.

- Naismith, Rory (2019). Citadel of the Saxons: The Rise of Early London. London, UK: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-3501-3568-0.